There is no scenario needed. The end of mankind (Mankind is used for simple directions for whom is unable to comprehend greater residence to Mankind, life and/or Lives) is a direct evidence, the mass of the abuse against the Earth's oceans. This the saddest state of affairs as the oceans reach to land to filter the suffocation, Mankind is throwing walls and gates to stop the oceans mass. A dynamic of land to ocean as the bone is to marrow would be the closest comparison however as the ocean reaches to the filtering system (soil, rock, fresh water) the pull back is not the fresh natural resources naturally expected, the pull is litter, sewage, basically man-made material.

As noticed in my country the United States of America hurricanes have been eye stopping from my view in San Francisco, this horror has been ever since I can remember and the fact that buildings are ripped to shreds, the waves of material washing both into the ocean and onto lands has been reason to gasp. To note the movement of mankind has been to arrive on a coast and then to move inland, this natural migration that has taken us from the coastlines due to the storms has been removed and mankind has enveloped better building i.e. construction to withstand the natural storms facing our coastlines, this is around the World and not held specific to the State of Florida.

Oct. 18, 2018 – Waste Management is running all collection routes in Panama City, ... recovery in the areas most significantly impacted by Hurricane Michael. ... the panhandle of Florida and was running all routes in the Panama City, Fla. and ... household appliances, bags of clothing, tree limbs, wood fencing, carpet and ...

Towards the migration and as exampled by the Nesting Birds, the Elephant, or just the Buffalo in America mankind has changed directions and thus the end of mankind is indeed man-made, and, it is made by every country, land, or Kingdom that is not practicing the management of their responsibility towards the oceans lines.

Study towards Nazca may provide the actual clock to know the cycle of lost seas and oceans as their drawings are seen only from the height that an airplane may provide, thinking wisely or more broadly I suppose Hot Air Balloons or a mountain peak may also or in-addition provide more to that map of understanding those drawings.

Due to our amazing performance in not only technology it was rally the gift of flight that gave the Nazca Lines our development towards greater success the opportunity to be greater managers of our Earth. As I loved the Space Race and as NASA was huge when I was a child I leave the rest of this fact to those whom would endeavour to more than religious aspect and condemnation, I leave to those whom understand that life is more than a bank.

Please remember that the Nazca Lines are very old however mankind only found them 80 years ago.

"The Nazca Lines are a collection of giant geoglyphs—designs or motifs etched into the ground—located in the Peruvian coastal plain about 250 miles (400 kilometers) south of Lima, Peru. Created by the ancient Nazca culture in South America, and depicting various plants, animals, and shapes, the 2,000-year-old Nazca Lines can only be fully appreciated when viewed from the air given their massive size. Despite being studied for over 80 years, the geoglyphs—which were designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1994—are still a mystery to researchers."

What Are the Nazca Lines?

"There are three basic types of Nazca Lines: straight lines, geometric designs and pictorial representations.There are more than 800 straight lines on the coastal plain, some of which are 30 miles (48 km) long. Additionally, there are over 300 geometric designs, which include basic shapes such as triangles, rectangles, and trapezoids, as well as spirals, arrows, zig-zags and wavy lines."

"The Nazca Lines are perhaps best known for the representations of about 70 animals and plants, some of which measure up to 1,200 feet (370 meters) long. Examples include a spider, hummingbird, cactus plant, monkey, whale, llama, duck, flower, tree, lizard and dog."

"The Nazca people also created other forms, such as a humanoid figure (nicknamed “The Astronaut”), hands and some unidentifiable depictions."

"In 2011, a Japanese team discovered a new geoglyph that appears to represent a scene of decapitation, which, at about 4.2 meters long and 3.1 meters wide, is far smaller than other Nazca figures and not easily seen from aerial surveys. The Nazca people were known to collect “trophy heads,” and research in 2009 revealed that the majority of trophy skulls came from the same populations as the people they were buried with (rather than outside cultures)."

"In 2016, the same team found another geoglyph, this time one that depicts a 98-foot-long (30-meter-long) mythical creature that has many legs and spotted markings, and is sticking out its tongue."

"And in 2018, Peruvian archaeologists announced they had discovered more than 50 new geoglyphs in the region, using drone technology to map the landmarks in unprecedented detail."

"Anthropologists believe the Nazca culture, which began around 100 B.C. and flourished from A.D. 1 to 700, created the majority of the Nazca Lines. The Chavin and Paracas cultures, which predate the Nazca, may have also created some of the geoglyphs."

"The Nazca Lines are located in the desert plains of the Rio Grande de Nasca river basin, an archaeological site that spans more than 75,000 hectares and is one of the driest places on Earth.

The desert floor is covered in a layer of iron oxide-coated pebbles of a deep rust color. The ancient peoples created their designs by removing the top 12 to 15 inches of rock, revealing the lighter-colored sand below. They likely began with small-scale models and carefully increased the models’ proportions to create the large designs." Read more at https://www.history.com/topics/south-america/nazca-lines

Ocean Worlds; https://www.nasa.gov/specials/ocean-worlds/

Water in the Solar System and Beyond

The story of oceans is the story of life. Oceans define our home planet, covering the majority of Earth’s surface and driving the water cycle that dominates our land and atmosphere. But more profound still, the story of our oceans envelops our home in a far larger context that reaches deep into the universe and places us in a rich family of ocean worlds that span our solar system and beyond.Origins of Oceans

Hydrogen was created in the Big Bang and oxygen in the cores of stars more massive than the Sun. Enormous amounts of water, in gaseous form, exist in the vast stellar nurseries of our galaxy.

The Hubble Space Telescope peered into the Helix Nebula and found water molecules. Hydrogen and oxygen, formed by different processes, combine to make water molecules in the ejected atmosphere of this dying star. The origins of our oceans are in the stars.

The Hubble Space Telescope peered into the Helix Nebula and found water molecules. Hydrogen and oxygen, formed by different processes, combine to make water molecules in the ejected atmosphere of this dying star. The origins of our oceans are in the stars.

Water molecules exist in the Orion Nebula and are still forming today. The nebula is composed mostly of hydrogen gas; other molecules are comparatively rare. Even so, the nebula is so vast that it creates enough water every day to fill Earth’s oceans 60 times over. Water, along with every other molecule created in these stellar nurseries, becomes raw material for the formation of new planetary systems.

Water molecules are abundant in planetary systems forming around other stars.

Water molecules have been found around the 20-million-year-old star Beta Pictoris, where a huge disk of dust and gas hints at collisions between comets, asteroids, and young planets (artist’s conception).

How did water arrive on Earth?

These small bodies are time capsules that contain tantalizing clues about what our solar system was like 4.5 billion years ago.

Most asteroids orbit the Sun between the planets Mars and Jupiter, but many swing nearer to Earth and even cross our orbit. Comets are found in the outer reaches of our solar system, either in the Kuiper Belt just beyond the orbit of Pluto, or in the vast, mysterious Oort Cloud that may extend halfway to the nearest star.

Over billions of years, countless comets and asteroids have collided with Earth, enriching our planet with water. Chemical markers in the water of our oceans suggest that most of the water came from asteroids. Recent observations hint that ice, and possibly even liquid water, exists in the interiors of asteroids and comets.

Everglades | Encyclopedia.com

https://www.encyclopedia.com/places/united-states-and-canada/us.../everglades

But during the development of Florida, the Everglades and surrounding .... palms, pine and mangrove forests, and solidly packed black muck (resulting from ...

Draining and development of the Everglades

Satellite image of the northern Everglades

with developed areas in 2001, including the Everglades Agricultural

Area (in red), Water Conservation Areas 1, 2, and 3, and the South Florida metropolitan area

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Satellite image of the southern Everglades with developed areas in 2001, including Everglades National Park, the Big Cypress Swamp, Florida Bay and the southern tip of the South Florida metropolitan area

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

Source: U.S. Geological Survey

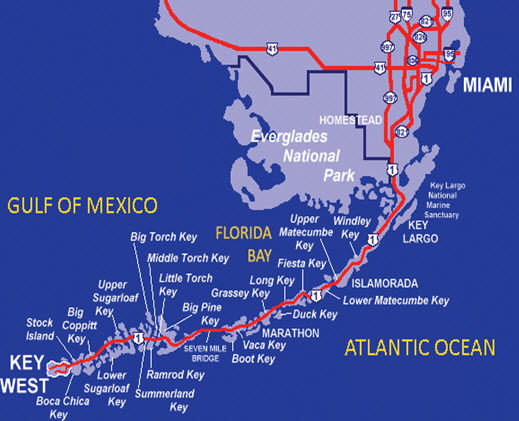

A pattern of political and financial motivation, and a lack of understanding of the geography and ecology of the Everglades have plagued the history of drainage projects. The Everglades are a part of a massive watershed that originates near Orlando and drains into Lake Okeechobee, a vast and shallow lake. As the lake exceeds its capacity in the wet season, the water forms a flat and very wide river, about 100 miles (160 km) long and 60 miles (97 km) wide. As the land from Lake Okeechobee slopes gradually to Florida Bay, water flows at a rate of half a mile (0.8 km) a day. Before human activity in the Everglades, the system comprised the lower third of the Florida peninsula. The first attempt to drain the region was made by real estate developer Hamilton Disston in 1881. Disston's sponsored canals were unsuccessful, but the land he purchased for them stimulated economic and population growth that attracted railway developer Henry Flagler. Flagler built a railroad along the east coast of Florida and eventually to Key West; towns grew and farmland was cultivated along the rail line.

During his 1904 campaign to be elected governor, Napoleon Bonaparte Broward promised to drain the Everglades, and his later projects were more effective than Disston's. Broward's promises sparked a land boom facilitated by blatant errors in an engineer's report, pressure from real estate developers, and the burgeoning tourist industry throughout south Florida. The increased population brought hunters who went unchecked and had a devastating impact on the numbers of wading birds (hunted for their plumes), alligators, and other Everglades animals.

Severe hurricanes in 1926 and 1928 caused catastrophic damage and flooding from Lake Okeechobee that prompted the Army Corps of Engineers to build a dike around the lake. Further floods in 1947 prompted an unprecedented construction of canals throughout southern Florida. Following another population boom after World War II, and the creation of the Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project, the Everglades was divided into sections separated by canals and water control devices that delivered water to agricultural and newly developed urban areas. However, in the late 1960s, following a proposal to construct a massive airport next to Everglades National Park, national attention turned from developing the land to restoring the Everglades.

Contents

Exploration

Opinion about the value of Florida to the Union was mixed: some thought it a useless land of swamps and horrible animals, while others thought it a gift from God for national prosperity.[4] In 1838 comments in The Army and Navy Chronicle supported future development of southern Florida:

[The] climate [is] most delightful; but, from want of actual observation, [it] could not speak so confidently of the soil, although, from the appearance of the surrounding vegetation, a portion of it, at least, must be rich. Whenever the aborigines shall be forced from their fastnesses, as eventually they must be, the enterprising spirit of our countrymen will very soon discover the sections best adapted to cultivation, and the now barren or unproductive everglades will be made to blossom like a garden. It is the general impression that these everglades are uninhabitable during the summer months, by reason of their being overflowed by the abundant rains of the season; but if it should prove that these inundations are caused or increased by obstructions to the natural courses of the rivers, as outlets to the numerous lakes, American industry will remove these obstructions.[5]

Map of the Everglades by the U.S. War Department in 1856: Military action during the Seminole Wars improved understanding of the features of the Everglades.

The final blame for the military stalemate was determined to lie not in military preparation, supplies, leadership, or superior tactics by the Seminoles, but in Florida's impenetrable terrain. An army surgeon wrote: "It is in fact a most hideous region to live in, a perfect paradise for Indians, alligators, serpents, frogs, and every other kind of loathsome reptile."[8] The land seemed to inspire extreme reactions of wonder or hatred. In 1870, an author described the mangrove forests as a "waste of nature's grandest exhibition to have these carnivals of splendid vegetation occurring in isolated places where it is but seldom they are seen."[9] A band of hunters, naturalists, and collectors ventured through in 1885, taking along with them the 17-year-old grandson of an early resident of Miami. The landscape unnerved the young man shortly after he entered the Shark River: "The place looked wild and lonely. About three o'clock it seemed to get on Henry's nerves and we saw him crying, he would not tell us why, he was just plain scared."[10]

In 1897, an explorer named Hugh Willoughby spent eight days canoeing with a party from the mouth of the Harney River to the Miami River. He wrote about his observations and sent them back to the New Orleans Times-Democrat. Willoughby described the water as healthy and wholesome, with numerous springs, and 10,000 alligators "more or less" in Lake Okeechobee. The party encountered thousands of birds near the Shark River, "killing hundreds, but they continued to return".[11] Willoughby pointed out that much of the rest of the country had been mapped and explored except for this part of Florida, writing, "(w)e have a tract of land one hundred and thirty miles long and seventy miles wide that is as much unknown to the white man as the heart of Africa."[12]

Drainage

As early as 1837, a visitor to the Everglades suggested the value of the land without the water:Could it be drained by deepening the natural outlets? Would it not open to cultivation immense tracts of rich vegetable soil? Could the waterpower, obtained by draining, be improved to any useful purpose? Would such draining render the country unhealthy? ... Many queries like these passed through our minds. They can only be solved by a thorough examination of the whole country. Could the waters be lowered ten feet, it would probably drain six hundred thousand acres; should this prove to be a rich soil, as would seem probable, what a field it would open for tropical productions! What facilities for commerce![3]Territorial representative David Levy proposed a resolution that was passed in Congress in 1842: "that the Secretary of War be directed to place before this House such information as can be obtained in relation to the practicability and probable expense of draining the everglades of Florida."[3] From this directive Secretary of the Treasury Robert J. Walker requested Thomas Buckingham Smith from St. Augustine to consult those with experience in the Everglades on the feasibility of draining them, saying that he had been told two or three canals to the Gulf of Mexico would be sufficient. Smith asked officers who had served in the Seminole Wars to respond, and many favored the idea, promoting the land as a future agricultural asset to the South. A few disagreed, such as Captain John Sprague, who wrote he "never supposed the country would excite an inquiry, other than as a hiding place for Indians, and had it occurred to me that so great an undertaking, one so utterly impracticable, as draining the Ever Glades was to be discussed, I should not have destroyed the scratch of pen upon a subject so fruitful, and which cannot be understood but by those who have waded the water belly deep and examined carefully the western coast by land and by water."[3]

Nevertheless, Smith returned a report to the Secretary of the Treasury asking for $500,000 to do the job.[13] The report is the first published study on the topic of the Everglades, and concluded with the statement:

The Ever Glades are now suitable only for the haunt of noxious vermin or the resort of pestilent reptiles. The statesman whose exertions shall cause the millions of acres they contain, now worse than worthless, to teem with the products of agricultural industry; that man who thus adds to the resources of his country ... will merit a high place in public favor, not only with his own generation, but with posterity. He will have created a State![3]Smith suggested cutting through the rim of the Everglades (known today as the Atlantic Coastal Ridge), connecting the heads of rivers to the coastline so that 4 feet (1.2 m) of water would be drained from the area. The result, Smith hoped, would yield farmland suitable for corn, sugar, rice, cotton, and tobacco.[14]

In 1850 Congress passed a law that gave several states wetlands within their state boundaries. The Swamp and Overflowed Lands Act ensured that the state would be responsible for funding the attempts at developing wetlands into farmlands.[14] Florida quickly formed a committee to consolidate grants to pay for such attempts, though attention and funds were diverted owing to the Civil War and Reconstruction. Not until after 1877 did attention return to the Everglades.

Hamilton Disston's canals

Hamilton Disston's land sale notice

Disston's engineers focused on Lake Okeechobee as well. As one colleague put it, "Okeechobee is the point to attack"; the canals were to be "equal or greater than the inflow from the Kissimmee valley, which is the source of all the evil."[18] Disston sponsored the digging of a canal 11 miles (18 km) long from Lake Okeechobee towards Miami, but it was abandoned when the rock proved denser than the engineers had expected. Though the canals lowered the groundwater, their capacity was inadequate for the wet season. A report that evaluated the failure of the project concluded: "The reduction of the waters is simply a question of sufficient capacity in the canals which may be dug for their relief".[19]

Though Disston's canals did not drain, his purchase primed the economy of Florida. It made news and attracted tourists and land buyers alike. Within four years property values doubled, and the population increased significantly.[15] One newcomer was the inventor Thomas Edison, who bought a home in Fort Myers.[20] Disston opened real estate offices throughout the United States and Europe, and sold tracts of land for $5 an acre, establishing towns on the west coast and in central Florida. English tourists in particular were targeted and responded in large numbers.[21] Florida passed its first water laws to "build drains, ditches, or water courses upon petition of two or more landowners" in 1893.[22]

Henry Flagler's railroads

Due to Disston's purchase, the IIF was able to sponsor railroad projects, and the opportunity presented itself when oil tycoon Henry Flagler became enchanted with St. Augustine during a vacation. He built the opulent Ponce de Leon Hotel in St. Augustine in 1888, and began buying land and building rail lines along the east coast of Florida, first from Jacksonville to Daytona, then as far south as Palm Beach in 1893. Flagler's establishment of "the Styx", a settlement for hotel and rail line workers across the river from the barrier island containing Palm Beach, became West Palm Beach.[23] Along the way he built resort hotels, transforming territorial outposts into tourist destinations and the land bordering the rail lines into citrus farms.[24]The winter of 1894–1895 produced a bitter frost that killed citrus trees as far south as Palm Beach. Miami resident Julia Tuttle sent Flagler a pristine orange blossom and an invitation to visit Miami, to persuade him to build the railroad farther south. Although he had earlier turned her down several times, Flagler finally agreed, and by 1896 the rail line had been extended to Biscayne Bay.[25] Three months after the first train arrived, the residents of Miami, 512 in all, voted to incorporate the town. Flagler publicized Miami as a "Magic City" throughout the United States and it became a prime destination for the extremely wealthy after the Royal Palm Hotel was opened.[26]

Broward's "Empire of the Everglades"

A canal lock in the Everglades Drainage District around 1915

Broward asked James O. Wright—an engineer on loan to the State of Florida from the USDA's Bureau of Drainage Investigations—to draw up plans for drainage in 1906. Two dredges were built by 1908, but had cut only 6 miles (9.7 km) of canals. The project quickly ran out of money, so Broward sold real estate developer Richard "Dicky" J. Bolles a million dollars worth of land in the Everglades, 500,000 acres (2,000 km2), before the engineer's report had been submitted.[30] Abstracts from Wright's report were given to the IIF stating that eight canals would be enough to drain 1,850,000 acres (7,500 km2) at a cost of a dollar an acre.[31] The abstracts were released to real estate developers who used them in their advertisements, and Wright and the USDA were pressed by the real estate industry to publicize the report as quickly as possible.[31] Wright's supervisor noted errors in the report, as well as undue enthusiasm for draining, and delayed its release in 1910. Different unofficial versions of the report circulated—some that had been altered by real estate interests—and a version hastily put together by Senator Duncan U. Fletcher called U.S. Senate Document 89 included early unrevised statements, causing a frenzy of speculation.[1]

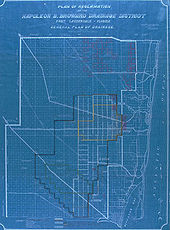

Blueprint for drainage canals in the Everglades in 1921

Though a few voices expressed skepticism of the report's conclusions—notably Frank Stoneman, the editor of the Miami News-Record (the forerunner of The Miami Herald)—the report was hailed as impeccable, coming from a branch of the U.S. government.[33] In 1912 Florida appointed Wright to oversee the drainage, and the real estate industry energetically misrepresented this mid-level engineer as the world's foremost authority on wetlands drainage, in charge of the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation.[1] However, the U.S. House of Representatives investigated Wright since no report had officially been published despite the money paid for it. Wright eventually retired when it was discovered that his colleagues disagreed with his conclusions and refused to approve the report's publication. One testified at the hearings: "I regard Mr. Wright as absolutely and completely incompetent for any engineering work".[34]

Governor Broward ran for the U.S. Senate in 1908 but lost. Broward and his predecessor, William Jennings, were paid by Richard Bolles to tour the state to promote drainage. Broward was elected to the Senate in 1910, but died before he could take office. He was eulogized across Florida for his leadership and progressive inspiration. Rapidly growing Fort Lauderdale paid him tribute by naming Broward County after him (the town's original plan had been to name it Everglades County). Land in the Everglades was being sold for $15 an acre a month after Broward died.[35] Meanwhile, Henry Flagler continued to build railway stations at towns as soon as the populations warranted them. News of the Panama Canal inspired him to connect his rail line to the closest deep water port. Biscayne Bay was too shallow, so Flagler sent railway scouts to explore the possibility of building the line through to the tip of mainland Florida. The scouts reported that not enough land was present to build through the Everglades, so Flagler instead changed the plan to build to Key West in 1912.[25]

Boom and plume harvesting

A group of tour buses leads prospective buyers to newly drained lots in Hialeah in 1921

With the increasing population in towns near the Everglades came hunting opportunities. Even decades earlier, Harriet Beecher Stowe had been horrified at the hunting by visitors, and she wrote the first conservation publication for Florida in 1877: "[t]he decks of boats are crowded with men, whose only feeling amid our magnificent forests, seems to be a wild desire to shoot something and who fire at every living thing on shore."[41] Otters and raccoons were the most widely hunted for their skins. Otter pelts could fetch between $8 and $15 each. Raccoons, more plentiful, only warranted 75 cents each in 1915. Hunting often went unchecked; on one trip, a Lake Okeechobee hunter killed 250 alligators and 172 otters.[42]

A 1904 magazine cutout showing the plumes for women's hats that were harvested from wading birds in the Everglades

Plume harvesting became a dangerous business. The Audubon Society became concerned with the amount of hunting being done in rookeries in the mangrove forests. In 1902, they hired a warden, Guy Bradley, to watch the rookeries around Cuthbert Lake. Bradley had lived in Flamingo within the Everglades, and was murdered in 1905 by one of his neighbors after he tried to prevent him from hunting.[47] Protection of birds was the reason for establishing the first wildlife refuge when President Theodore Roosevelt set Pelican Island as a sanctuary in 1903.

In the 1920s, after birds were protected and alligators hunted nearly to extinction, Prohibition created a living for those willing to smuggle alcohol into the U.S. from Cuba. Rum-runners used the vast Everglades as a hiding spot: there were never enough law enforcement officers to patrol it.[48] The advent of the fishing industry, the arrival of the railroad, and the discovery of the benefits of adding copper to Okeechobee muck soon created unprecedented numbers of residents in new towns like Moore Haven, Clewiston, and Belle Glade. By 1921, 2,000 people lived in 16 new towns around Lake Okeechobee.[3] Sugarcane became the primary crop grown in south Florida and it began to be mass-produced. Miami experienced a second real estate boom that earned a developer in Coral Gables $150 million and saw undeveloped land north of Miami sell for $30,600 an acre.[49] Miami became cosmopolitan and experienced a renaissance of architecture and culture. Hollywood movie stars vacationed in the area and industrialists built lavish homes. Miami's population multiplied fivefold, and Ft. Lauderdale and Palm Beach grew many times over as well. In 1925, Miami newspapers published editions weighing over 7 pounds (3.2 kg), most of it real estate advertising.[50] Waterfront property was the most highly valued. Mangrove trees were cut down and replaced with palm trees to improve the view. Acres of south Florida slash pine were taken down, some for lumber, but the wood was found to be dense and it split apart when nails were driven into it. It was also termite-resistant, but homes were needed quickly. Most of the pine forests in Dade County were cleared for development.[51]

Hurricanes

The canals proposed by Wright were unsuccessful in making the lands south of Lake Okeechobee fulfill the promises made by real estate developers to local farmers. The winter of 1922 was unseasonably wet and the region was underwater. The town of Moore Haven received 46 inches (1,200 mm) of rain in six weeks in 1924.[52] Engineers were pressured to regulate the water flow, not only for farmers but also for commercial fishers, who often requested conflicting water levels in the lake. Fred Elliot, who was in charge of building the canals after James Wright retired, commented: "A man on one side of the canal wants it raised for his particular use and a man on the other side wants it lowered for his particular use".[53]1926 Miami Hurricane

Remains of a bridge damaged during the 1926 Miami Hurricane.

Pictures of the destruction in the town of Okeechobee in 1928

1928 Okeechobee Hurricane

The weather was unremarkable for two years. In 1928, construction was completed on the Tamiami Trail, named because it was the only road spanning between Tampa and Miami. The builders attempted to construct the road several times before they blasted the muck down to the limestone, filled it with rock and paved over it.[60] Hard rains in the summer caused Lake Okeechobee to rise several feet; this was noticed by a local newspaper editor who demanded it be lowered. However, on September 16, 1928 came a massive storm, now known as the 1928 Okeechobee Hurricane. Thousands drowned when Lake Okeechobee breached its levees; the range of estimates of the dead spanned from 1,770 (according to the Red Cross) to 3,000 or more.[61] Many were swept away and never recovered.[54][62] The majority of the dead were black migrant workers who had recently settled in or near Belle Glade. The catastrophe made national news, and although the governor again refused aid, after he toured the area and counted 126 bodies still unburied or uncollected a week after the storm, he activated the National Guard to assist in the cleanup,[54] and declared in a telegram: "Without exaggeration, the situation in the storm area beggars description".[63]Herbert Hoover Dike

A sign advertising the completion of the Herbert Hoover Dike

A massive canal 80 feet (24 m) wide and 6 feet (1.8 m) deep was also dug through the Caloosahatchee River; when the lake rose too high, the excess water left through the canal to the Gulf of Mexico. Exotic trees were planted along the north shore levee: Australian pines, Australian oaks, willows, and bamboo.[12] More than $20 million was spent on the entire project. Sugarcane production soared after the dike and canal were built. The populations of the small towns surrounding the lake jumped from 3,000 to 9,000 after World War II.[65]

Drought

The effects of the Hoover Dike were seen immediately. An extended drought occurred in the 1930s, and with the wall preventing water leaving Lake Okeechobee and canals and ditches removing other water, the Everglades became parched. Peat turned to dust, and salty ocean water entered Miami's wells. When the city brought in an expert to investigate, he discovered that the water in the Everglades was the area's groundwater—here, it appeared on the surface. Draining the Everglades removed this groundwater, which was replaced by ocean water seeping into the area's wells.[66] In 1939, 1 million acres (4,000 km2) of Everglades burned, and the black clouds of peat and sawgrass fires hung over Miami. Underground peat fires burned roots of trees and plants without burning the plants in some places.[67] Scientists who took soil samples before draining had not taken into account that the organic composition of peat and muck in the Everglades was mixed with bacteria that added little to the process of decomposition underwater because they were not mixed with oxygen. As soon as the water was drained and oxygen mixed with the soil, the bacteria began to break down the soil. In some places, homes had to be moved on to stilts and 8 feet (2.4 m) of topsoil was lost.[68]Conservation attempts

President Harry Truman dedicating Everglades National Park on December 6, 1947

Although the idea of protecting a portion of the Everglades arose in 1905, a crystallized effort was formed in 1928 when Miami landscape designer Ernest F. Coe established the Everglades Tropical National Park Association. It had enough support to be declared a national park by Congress in 1934, but there was not enough money during the Great Depression to buy the proposed 2,000,000 acres (8,100 km2) for the park. It took another 13 years for it to be dedicated on December 6, 1947. [70] One month before the dedication of the park, the former editor of The Miami Herald and freelance writer Marjory Stoneman Douglas published her first book, The Everglades: River of Grass. After researching the region for five years, she described the history and ecology of the south of Florida in great detail, characterizing the Everglades as a river instead of a stagnant swamp.[71] Douglas later wrote, "My colleague Art Marshall said that with [the words "River of Grass"] I changed everybody's knowledge and educated the world as to what the Everglades meant".[72] The last chapter was titled "The Eleventh Hour" and warned that the Everglades were approaching death, although the course could be reversed.[73] Its first printing sold out a month after its release.[74]

Flood control

Coinciding with the dedication of Everglades National Park, 1947 in south Florida saw two hurricanes and a wet season responsible for 100 inches (250 cm) of rain, ending the decade-long drought. Although there were no human casualties, cattle and deer were drowned and standing water was left in suburban areas for months. Agricultural interests lost about $59 million. The embattled head of the Everglades Drainage District carried a gun for protection after being threatened.[75]Central and Southern Florida Flood Control Project

In 1948 Congress approved the Central and Southern Florida Project for Flood Control and Other Purposes (C&SF) and consolidated the Everglades Drainage District and the Okeechobee Flood Control District under this.[76] The C&SF used four methods in flood management: levees, water storage areas, canal improvements, and large pumps to assist gravity. Between 1952 and 1954 in cooperation with the state of Florida it built a levee 100 miles (160 km) long between the eastern Everglades and suburbs from Palm Beach to Homestead, and blocked the flow of water into populated areas.[77] Between 1954 and 1963 it divided the Everglades into basins. In the northern Everglades were Water Conservation Areas (WCAs), and the Everglades Agricultural Area (EAA) bordering to the south of Lake Okeechobee. In the southern Everglades was Everglades National Park. Levees and pumping stations bordered each WCA, which released water in drier times and removed it and pumped it to the ocean or Gulf of Mexico in times of flood. The WCAs took up about 37 percent of the original Everglades.[78]During the 1950s and 1960s the South Florida metropolitan area grew four times as fast as the rest of the nation. Between 1940 and 1965, 6 million people moved to south Florida: 1,000 people moved to Miami every week.[79] Urban development between the mid-1950s and the late 1960s quadrupled. Much of the water reclaimed from the Everglades was sent to newly developed areas.[80] With metropolitan growth came urban problems associated with rapid expansion: traffic jams; school overcrowding; crime; overloaded sewage treatment plants; and, for the first time in south Florida's urban history, water shortages in times of drought.[81]

The C&SF constructed over 1,000 miles (1,600 km) of canals, and hundreds of pumping stations and levees within three decades. It produced a film, Waters of Destiny, characterized by author Michael Grunwald as propaganda, that likened nature to a villainous, shrieking force of rage and declared the C&SF's mission was to tame nature and make the Everglades useful.[82] Everglades National Park management and Marjory Stoneman Douglas initially supported the C&SF, as it promised to maintain the Everglades and manage the water responsibly. However, an early report by the project reflected local attitudes about the Everglades as a priority to people in nearby developed areas: "The aesthetic appeal of the Park can never be as strong as the demands of home and livelihood. The manatee and the orchid mean something to people in an abstract way, but the former cannot line their purse, nor the latter fill their empty bellies."[83]

Establishment of the C&SF made Everglades National Park completely dependent upon another political entity for its survival.[84] One of the C&SF's projects was Levee 29, laid along the Tamiami Trail on the northern border of the park. Levee 29 featured four flood control gates that controlled all the water entering Everglades National Park; before construction, water flowed in through open drain pipes. The period from 1962 to 1965 was one of drought for the Everglades, and Levee 29 remained closed to allow the Biscayne Aquifer—the fresh water source for South Florida—to stay filled.[85] Animals began to cross Tamiami Trail for the water held in WCA 3, and many were killed by cars. Biologists estimate the population of alligators in Everglades National Park was halved; otters nearly became extinct.[80] The populations of wading birds had been reduced by 90 percent from the 1940s.[86] When park management and the U.S. Department of the Interior asked the C&SF for assistance, the C&SF offered to build a levee along the southern border of Everglades National Park to retain waters that historically flowed through the mangroves and into Florida Bay. Though the C&SF refused to send the park more water, they constructed Canal 67, bordering the east side of the park and carrying excess water from Lake Okeechobee to the Atlantic.[80]

Everglades Agricultural Area

A 2003 U.S. Geological Survey photo showing the border between Water Conservation Area 3 (bottom) with water, and Everglades National Park, dry (top)

Fields in the EAA are typically 40 acres (16 ha), on two sides bordered by canals that are connected to larger ones by which water is pumped in or out depending on the needs of the crops. The water level for sugarcane is ideally maintained at 20 inches (51 cm) below the surface soil, and after the cane is harvested, the stalks are burned.[92] Vegetables require more fertilizer than sugarcane, though the fields may resemble the historic hydrology of the Everglades by being flooded in the wet season. Sugarcane, however, requires water in the dry season. The fertilizers used on vegetables, along with high concentrations of nitrogen and phosphorus that are the by-product of decayed soil necessary for sugarcane production, were pumped into WCAs south of the EAA, predominantly to Everglades National Park. The introduction of large amounts of these let exotic plants take hold in the Everglades.[93] One of the defining characteristics of natural Everglades ecology is its ability to support itself in a nutrient-poor environment, and the introduction of fertilizers began to change this ecology.[94]

Turning point

A turning point for development in the Everglades came in 1969 when a replacement airport was proposed as Miami International Airport outgrew its capacities. Developers began acquiring land, paying $180 an acre in 1968, and the Dade County Port Authority (DCPA) bought 39 square miles (100 km2) in the Big Cypress Swamp without consulting the C&SF, management of Everglades National Park or the Department of the Interior. Park management learned of the official purchase and agreement to build the jetport from The Miami Herald the day it was announced.[84] The DCPA bulldozed the land it had bought, and laid a single runway it declared was for training pilots. The new jetport was planned to be larger than O'Hare, Dulles, JFK, and LAX airports combined; the location chosen was 6 miles (9.7 km) north of the Everglades National Park, within WCA 3. The deputy director of the DCPA declared: "This is going to be one of the great population centers of America. We will do our best to meet our responsibilities and the responsibilities of all men to exercise dominion over the land, sea, and air above us as the higher order of man intends."[95]The C&SF brought the jetport proposal to national attention by mailing letters about it to 100 conservation groups in the U.S.[84] Initial local press reaction condemned conservation groups who immediately opposed the project. Business Week reported real estate prices jumped from $200 to $800 an acre surrounding the planned location, and Life wrote of the expectations of the commercial interests in the area.[84] The U.S. Geological Survey's study of the environmental impact of the jetport started, "Development of the proposed jetport and its attendant facilities ... will inexorably destroy the south Florida ecosystem and thus the Everglades National Park".[96] The jetport was intended to support a community of a million people and employ 60,000. The DCPA director was reported in Time saying, "I'm more interested in people than alligators. This is the ideal place as far as aviation is concerned."[97]

When studies indicated the proposed jetport would create 4,000,000 US gallons (15,000,000 L) of raw sewage a day and 10,000 short tons (9,100 t) of jet engine pollutants a year, the national media snapped to attention. Science magazine wrote, in a series on environmental protection highlighting the jetport project, "Environmental scientists have become increasingly aware that, without careful planning, development of a region and the conservation of its natural resources do not go hand in hand".[98] The New York Times called it a "blueprint for disaster",[99] and Wisconsin senator Gaylord Nelson wrote to President Richard Nixon voicing his opposition: "It is a test of whether or not we are really committed in this country to protecting our environment."[97] Governor Claude Kirk withdrew his support for the project, and the 78-year-old Marjory Stoneman Douglas was persuaded to go on tour to give hundreds of speeches against it. She established Friends of the Everglades and encouraged more than 3,000 members to join. Initially the U.S. Department of Transportation pledged funds to support the jetport, but after pressure, Nixon overruled the department. He instead established Big Cypress National Preserve, announcing it in the Special Message to the Congress Outlining the 1972 Environmental Program.[100] Following the jetport proposition, restoration of the Everglades became not only a statewide priority, but an international one as well. In the 1970s the Everglades were declared an International Biosphere Reserve and a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, and a Wetland of International Importance by the Ramsar Convention,[101][102] making it one of only three locations on earth that have appeared on all three lists.[103]

See also

- Environmental issues in Florida

- Indigenous people of the Everglades region

- Seminole

- History of Miami, Florida

- Restoration of the Everglades

- Swamplands Act of 1850

Notes and references

- Maltby, E., P.J. Dugan, "Wetland Ecosystem Management, and Restoration: An International Perspective" in Everglades: The Ecosystem and its Restoration, Steven Davis and John Ogden, eds. (1994), Delray Beach, Fla.: St. Lucie Press. ISBN 0-9634030-2-8

Bibliography

- Barnett, Cynthia (2007). Mirage: Florida and the Vanishing Water of the Eastern U.S.. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-11563-4

- Carter, W. Hodding (2004). Stolen Water: Saving the Everglades from its Friends, Foes, and Florida. Atria Books. ISBN 0-7434-7407-4

- Caulfield, Patricia (1970) Everglades. New York: Sierra Club / Ballantine Books.

- Douglas, Marjory (1947). The Everglades: River of Grass. R. Bemis Publishing, Ltd. ISBN 0-912451-44-0

- Douglas, Marjory; Rothchild, John (1987). Marjory Stoneman Douglas: Voice of the River. Pineapple Press. ISBN 0-910923-33-7

- Grunwald, Michael (2006). The Swamp: The Everglades, Florida, and the Politics of Paradise. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-7432-5107-5

- Lodge, Thomas E. (1994). The Everglades Handbook: Understanding the Ecosystem. CRC Press. ISBN 1-56670-614-9

- McCally, David (1999). The Everglades: An Environmental History. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. Available as an etext; Boulder, Colo.: NetLibrary, 2001. ISBN 0-8130-2302-5

- Tebeau, Charlton (1968). Man in the Everglades: 2000 Years of Human History in the Everglades National Park. Coral Gables: University of Miami Press.

No comments:

Post a Comment