Cantore Arithmetic is able to state that understanding comes at an advance of the abuse that neglected the task to understand comprehension of Nicola Tesla , Inventor of the AC power system and the Tesla power coil, Nikola Tesla moves into The New Yorker Hotel, occupying rooms 3327 and 3328. Tesla lived in the hotel until his death on January 7, 1943: About 8,350,000 results (0.56 seconds). Inventors are not necessarily engineers or scientists. This cadence to task gave Nicola Tesla an Alan Turing to perhaps his work to the next tack: In girth.

The balance at thought is an Albert Einstein that must have calculated the avenue of his birth to the pier that gave no water as the oceans were in barge. To date the repeated values at the world rope is a balloon that helium impaired to say that gasoline is Kentucky Fried Chicken. These perhaps to scope magnified at the problem solver for self: Nostradamus baring Edgar Cayce to tact!

Perhaps the depth does relay as with a cadence that the billets of the Bay Bridge counter to the toll of such treasures that coins have been based at the mouth of the belly of the seas that name rose for the Bering Sea. A marginal sea of the Northern Pacific Ocean, it forms, along with the Bering Strait, the divide between the two largest landmasses: Edit: Michelangelo di Lodovico Buonarroti Simoni painted the Sistine Chapel: Ceiling.

These balance the work of known natural events to structure Cantore Arithmetic only as the chapel at the location is in roof. This action to the streets of city have laid plan to the horse in introduction to explanation of a man on his back with paint as the Wizard of Oz had in description the bay: Horse. The twilight twas is not for the form to what is the word.

Now for the pieces; cloud to ceiling on the plank of structure delivers the Chinese to technique and provision to India for the yeast as the bread is still by bush at Boudin!!

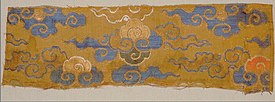

Xiangyun (Auspicious clouds)

Xiangyun (simplified Chinese: 祥云; traditional Chinese: 祥雲; pinyin: xiángyún), are traditional Chinese stylized clouds decorative patterns.[1][2]: 581 [3]: 132 They are also known as yunwen (云纹; 雲紋; 'cloud motif'), auspicious clouds, lucky clouds, and sometimes abbreviated as clouds (云; 雲; yún) in English.[4] A type of xiangyun which was perceived as being especially auspicious is the five-colouredclouds, called qingyun (庆云; 慶雲; qìngyún), which is more commonly known as wuse yun (五色云; 五色雲; wǔsèyún; 'five colour cloud') or wucai xiangyun (五彩祥云; 五彩祥雲; wǔcǎi xiángyún; 'Five-coloured auspicious clouds'), which was perceived as an indicator of a kingdom at peace.[1][2]: 579 [note 1]

Xiangyun are one of the most auspicious patterns used in China and have a very long history.[5] Clouds motifs have appeared in China as early as the Shang dynasty and Eastern Zhou dynasty.[1][2][3]: 132 [6]: 25 They are one of the oldest decorations and ornaments used in Chinese art, Chinese architecture, furniture, and Chinese textile and Chinese clothing.[6]: 25 [7][2]: 579–582 When used on Chinese textile, xiangyun can take many various forms, including having the appearance of Chinese character wan (卐; wàn) or the appearance of the lingzhi.[2]: 582 [4][note 2] Xiangyun motif has been transmitted from generation to generation in China and is still valued in present days China for its aesthetic and cultural value.[5][7] Xiangyun was also introduced in Japan, where it became known as zuiun.[8]

Cultural significance and symbolism[edit]

Auspicious significance[edit]

Clouds motifs is rooted in agrarian society culture of the Chinese people.[2]: 481 Clouds are associated with good luck as the cloud makes rain which moisten all things, and therefore, it brings good fortune to people.[3]: 133

In Chinese language, clouds are called yun (云; 雲; yún) which is a homonym for the Chinese character yun "good fortune" (运; 運; yùn).[2]: 579

In Chinese culture, clouds (especially the five-coloured clouds) are perceived as an auspicious sign (e.g. an omen of peace[4]),[2]: 579 a symbol of Heaven,[4] and the expression of the Will of Heaven.[1][note 3] They also symbolize happiness and good luck.[9]: 99

Association with Taoism and Chinese cosmology[edit]

The clouds physical characteristics (being wispy and vaporous in nature) were associated with the Taoist concept of qi (气; 氣), especially yuanqi,[3]: 133 and the cosmological forces at work;[1][note 4] i.e. the yuanqi was the origins of the Heavens and Earth, and all things were created from the interaction between the yin and yang.[3]: 133 As the ancient pictograph of qi looked like rising steam, ancient Chinese believed that the Qi was the clouds and the clouds was the qi.[3]: 133

Association with deities, Chinese Immortals, and the Will of Heaven[edit]

Early in its history, clouds were often perceived under a ritual or liturgical lens where xiangyun were often times associated with the presence of deities and were considered a good omen indicating the arrival of good fortune.[1]

In Chinese mythologies, mythological creatures and deities use clouds as their mount.[3]: 133 [9]: 99 Clouds were also closely associated with the Chinese immortals (called xian) and their residence on Mount Penglai.[1]

Xiangyun were also symbolic motifs which implied immortality.[6]: 25

In the Han dynasty, auspicious signs (祥瑞; xiángruì) were popular; the Han dynasty Emperors would interpret xiangrui as an indicator of the Mandate of Heaven. In that period, the sighting of xiangyun in the sky and its association its auspicious characteristics was recorded in the Chapter Fengshanshu《封禪書》of the Shiji by Sima Qian, where it was described as "an unusual cloud formation [...] in the sky northeast of Chang'an a supernatural emanation had appeared, made of five colours [五彩] and shaped like a man’s hat"; the record continues with the following suggestion: "since Heaven has sent down this auspicious sign [referring to xiangyun], it is right that places of worship should be set up to offer sacrifices to the Lord on High in an answer to his omen".[1][10] In this period, the people of the Han dynasty therefore interpreted the apparitions of the five-coloured clouds in the sky as an expression of the Will of Heaven.[1]

History[edit]

| Xiangyun | |

|---|---|

Auspicious clouds, China, 17th-18th century | |

| Chinese name | |

| Traditional Chinese | 祥雲 |

| Simplified Chinese | 祥云 |

| Literal meaning | Auspicious clouds |

| Hanyu Pinyin | Xiángyún |

| Japanese name | |

| Kanji | 瑞雲 |

| Katakana | ずいうん |

| Romanization | Zuiun |

| English name | |

| English | Auspicious clouds/ clouds/ lucky clouds |

Ancient[edit]

Earliest yunleiwen pattern appeared in the Sanxingdui archaeological site, dated from 1131 BC to 1012 BC, on the jade zhang blade and on a bronze altar.[11]

Cloud motifs in China appeared as early as the Eastern Zhou dynasty and earlier.[1][2]: 482 They can be traced back to the vortex pattern used to decorate prehistoric painted pottery,[3]: 132–133 to the yunleiwen (云雷纹; 雲雷紋; yúnléiwén; 'cloud thunder motif'),[3]: 133 , which somewhat resemble the meanderpatterns, and to the cloud scroll patterns which were used in the Warring States Period.[3]: 133 All these early depictions of cloud motifs however eventually evolved with time changing in shape and colours[2]: 482 and further matured in the Han dynasty.[3]: 133

Han dynasty[edit]

In the Han dynasty, stories on Chinese immortals became popular and the popular of the cloud motif grew.[3]: 133 The cloud patterns gained more artistic beauty which were associated with the concept of immortality[3]: 133 and were formalized.[9]: 99 These cloud motifs were then used in various ways, such as in architecture, clothing, utensils, and coffins.[3]: 133 [9]: 99 They were also combined with other animals (e.g. birds) and mythological creatures (e.g. Chinese dragons).[3]: 133

Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties[edit]

During the Wei, Jin, Northern and Southern dynasties, the cloud motifs looked like streamers.[3]: 133

Sui and Tang dynasty[edit]

In the Sui and Tang dynasties, the cloud motifs looked like flowers; it looked realistic, plump, and very decorative.[3]: 133 They became an established theme on ceramic ware since the Tang dynasty and would symbolize happiness or good luck.[9]: 99 Their shapes became more and more diverse in the Tang dynasty and cloud motifs were coupled with the images of other creatures.[6]: 25

Song and Yuan dynasties[edit]

In the Song and Yuan dynasties, the cloud motifs were ruyi-like.[3]: 133

Ming dynasty[edit]

In the Ming dynasty, there was a unique form of cloud motifs which looked like a gourd.[3]: 133

Qing dynasty[edit]

Modern[edit]

The yunleiwen patterns remained popular in modern times and continue to be used on contemporary tableware.[12]: 45

Shapes of auspicious clouds[edit]

Yunleiwen/ Yunwen/ Leiwen[edit]

The yunleiwen was also known as cloud-and-thunder motif, meander border, or meander order in English.[2]: 482 [12]: 45 It was sometimes also referred as yunwen (cloud pattern) or leiwen (thunder pattern) in Chinese.[12]: 45 It was a form of repetitive pattern similar to a meander.[9]: 4 It came in various shapes;[13][9]: 4 some looked like juxtaposed squared-off spirals;[3]: 133 others looked like stylized angular "S" repeated designs which could be sometimes sometimes connected or disconnected.[12]: 45

The yunleiwen pattern was a symbol of the life-giving and the abundance in harvest that the rain would bring to the people in an agrarian society.[12]: 45 [9]: 4 The pattern may have been derived from the symbols and ancient characters for clouds and thunder which had been used by the ancient Chinese when performing the worship of rain rituals.[14] The yunleiwen can be found in the textiles dating to the Shang and Zhou dynasties[2]: 482 and in sacred bronze vessels of the Zhou dynasty.[9]: 4

The yunleiwen motif continues to be used in 21st century as border decoration on contemporary tableware.[12]: 45

Influences and derivatives[edit]

Central Asia and Islamic art[edit]

Chinese arts have increasingly impacted arts of Central Asia and Iran, such as painting and pottery, during the Tang dynasty.[15]: 1ixiii Under the Liao dynasty, the Chinese cloud motifs coupled with animal motifs were gradually introduced to Central Asia.[6]: 25

Following the Mongol invasion, Chinese influences on the arts of Central Asia and Iran reached its peak during the Islamic period; it was a period when Chinese models and motifs influenced Persian designs and thus, the Chinese ways of depicting clouds, mountains, trees and facial features were imitated and adopted.[15]: 1ixiii In the late 13th century, the Iranians especially favoured cloud motifs (often coupled with animals) in their arts, including textiles, and paintings as landscape elements.[6]: 25

Japan[edit]

Xiangyun was introduced from China to Japan where it became known as zuiun or Reishi mushroom cloud;[8] under the influence of China, Japan started to use various forms of clouds designs in the Asuka period.[16] They gained different names based on their shapes; e.g. kumodori (soft and drifting clouds).[16] Zuiun is characterized by a swirly shape which looks like a reishi mushroom and also express an auspicious omen.[8] Some clouds patterns in Japan were localized and developed from the shape of the Chinese clouds; such as the clouds developed by Ninsei. which were simpler in shape and were presented as mass of clouds instead of a group of clouds.[17] Ninsei's cloud-style was then adapted and later evolved into cloud outline which were then applied on all types of Japanese ceramics.[17]

See also[edit]

Generalized quantifier

In formal semantics, a generalized quantifier (GQ) is an expression that denotes a set of sets. This is the standard semantics assigned to quantifiednoun phrases. For example, the generalized quantifier every boy denotes the set of sets of which every boy is a member:

This treatment of quantifiers has been essential in achieving a compositional semantics for sentences containing quantifiers.[1][2]

Type theory[edit]

A version of type theory is often used to make the semantics of different kinds of expressions explicit. The standard construction defines the set of types recursively as follows:

- e and t are types.

- If a and b are both types, then so is

- Nothing is a type, except what can be constructed on the basis of lines 1 and 2 above.

Given this definition, we have the simple types e and t, but also a countable infinity of complex types, some of which include:

- Expressions of type e denote elements of the universe of discourse, the set of entities the discourse is about. This set is usually written as . Examples of type e expressions include John and he.

- Expressions of type t denote a truth value, usually rendered as the set , where 0 stands for "false" and 1 stands for "true". Examples of expressions that are sometimes said to be of type t are sentences or propositions.

- Expressions of type denote functions from the set of entities to the set of truth values. This set of functions is rendered as . Such functions are characteristic functions of sets. They map every individual that is an element of the set to "true", and everything else to "false." It is common to say that they denote sets rather than characteristic functions, although, strictly speaking, the latter is more accurate. Examples of expressions of this type are predicates, nouns and some kinds of adjectives.

- In general, expressions of complex types denote functions from the set of entities of type to the set of entities of type , a construct we can write as follows: .

We can now assign types to the words in our sentence above (Every boy sleeps) as follows.

- Type(boy) =

- Type(sleeps) =

- Type(every) =

- Type(every boy) =

and so we can see that the generalized quantifier in our example is of type

Thus, every denotes a function from a set to a function from a set to a truth value. Put differently, it denotes a function from a set to a set of sets. It is that function which for any two sets A,B, every(A)(B)= 1 if and only if .

Typed lambda calculus[edit]

A useful way to write complex functions is the lambda calculus. For example, one can write the meaning of sleeps as the following lambda expression, which is a function from an individual x to the proposition that x sleeps.

We can now write the meaning of every with the following lambda term, where X,Y are variables of type :

If we abbreviate the meaning of boy and sleeps as "B" and "S", respectively, we have that the sentence every boy sleeps now means the following:

The expression every is a determiner. Combined with a noun, it yields a generalized quantifier of type .

Properties[edit]

Monotonicity[edit]

Monotone increasing GQs[edit]

A generalized quantifier GQ is said to be monotone increasing (also called upward entailing) if, for every pair of sets X and Y, the following holds:

- if , then GQ(X) entails GQ(Y).

The GQ every boy is monotone increasing. For example, the set of things that run fast is a subset of the set of things that run. Therefore, the first sentence below entails the second:

- Every boy runs fast.

- Every boy runs.

Monotone decreasing GQs[edit]

A GQ is said to be monotone decreasing (also called downward entailing) if, for every pair of sets X and Y, the following holds:

- If , then GQ(Y) entails GQ(X).

An example of a monotone decreasing GQ is no boy. For this GQ we have that the first sentence below entails the second.

- No boy runs.

- No boy runs fast.

The lambda term for the determiner no is the following. It says that the two sets have an empty intersection.

- Good: No boy has any money.

- Bad: *Every boy has any money.

Non-monotone GQs[edit]

A GQ is said to be non-monotone if it is neither monotone increasing nor monotone decreasing. An example of such a GQ is exactly three boys. Neither of the following sentences entails the other.

- Exactly three students ran.

- Exactly three students ran fast.

The first sentence does not entail the second. The fact that the number of students that ran is exactly three does not entail that each of these students ran fast, so the number of students that did that can be smaller than 3. Conversely, the second sentence does not entail the first. The sentence exactly three students ran fast can be true, even though the number of students who merely ran (i.e. not so fast) is greater than 3.

The lambda term for the (complex) determiner exactly three is the following. It says that the cardinality of the intersection between the two sets equals 3.

Conservativity[edit]

A determiner D is said to be conservative if the following equivalence holds:

- Every boy sleeps.

- Every boy is a boy who sleeps.

It has been proposed that all determiners—in every natural language—are conservative.[2] The expression only is not conservative. The following two sentences are not equivalent. But it is, in fact, not common to analyze only as a determiner. Rather, it is standardly treated as a focus-sensitive adverb.

- Only boys sleep.

- Only boys are boys who sleep.

See also[edit]

Plural

This article includes a list of general references, but it lacks sufficient corresponding inline citations. (December 2020) |

| Grammatical features |

|---|

The plural (sometimes abbreviated as pl., pl, or pl), in many languages, is one of the values of the grammatical category of number. The plural of a noun typically denotes a quantity greater than the default quantity represented by that noun. This default quantity is most commonly one (a form that represents this default quantity of one is said to be of singular number). Therefore, plurals most typically denote two or more of something, although they may also denote fractional, zero or negative amounts. An example of a plural is the English word cats, which corresponds to the singular cat.

Words of other types, such as verbs, adjectives and pronouns, also frequently have distinct plural forms, which are used in agreement with the number of their associated nouns.

Some languages also have a dual (denoting exactly two of something) or other systems of number categories. However, in English and many other languages, singular and plural are the only grammatical numbers, except for possible remnants of dual number in pronouns such as both and either.

Use in systems of grammatical number[edit]

In many languages, there is also a dual number (used for indicating two objects). Some other grammatical numbers present in various languages include trial (for three objects) and paucal (for an imprecise but small number of objects). In languages with dual, trial, or paucal numbers, plural refers to numbers higher than those. However, numbers besides singular, plural, and (to a lesser extent) dual are extremely rare. Languages with numerical classifiers such as Chinese and Japanese lack any significant grammatical number at all, though they are likely to have plural personal pronouns.

Some languages (like Mele-Fila) distinguish between a plural and a greater plural. A greater plural refers to an abnormally large number for the object of discussion. The distinction between the paucal, the plural, and the greater plural is often relative to the type of object under discussion. For example, in discussing oranges, the paucal number might imply fewer than ten, whereas for the population of a country, it might be used for a few hundred thousand.

The Austronesian languages of Sursurunga and Lihir have extremely complex grammatical number systems, with singular, dual, paucal, greater paucal, and plural.

Traces of the dual and paucal can be found in some Slavic and Baltic languages (apart from those that preserve the dual number, such as Slovene). These are known as "pseudo-dual" and "pseudo-paucal" grammatical numbers. For example, Polish and Russian use different forms of nouns with the numerals 2, 3, or 4 (and higher numbers ending with these[citation needed]) than with the numerals 5, 6, etc. (genitive singular in Russian and nominative plural in Polish in the former case, genitive plural in the latter case). Also some nouns may follow different declension patterns when denoting objects which are typically referred to in pairs. For example, in Polish, the noun "oko", among other meanings, may refer to a human or animal eye or to a drop of oil on water. The plural of "oko" in the first meaning is "oczy" (even if actually referring to more than two eyes), while in the second it is "oka" (even if actually referring to exactly two drops).

Traces of dual can also be found in Modern Hebrew. Biblical Hebrew had grammatical dual via the suffix -ạyim as opposed to ־ים -īm for masculine words. Contemporary use of a true dual number in Hebrew is chiefly used in words regarding time and numbers. However, in Biblical and Modern Hebrew, the pseudo-dual as plural of "eyes" עין / עינים ʿạyin / ʿēnạyim "eye / eyes" as well as "hands", "legs" and several other words are retained. For further information, see Dual (grammatical number) § Hebrew.

Certain nouns in some languages have the unmarked form referring to multiple items, with an inflected form referring to a single item. These cases are described with the terms collective number and singulative number. Some languages may possess a massive plural and a numerative plural, the first implying a large mass and the second implying division. For example, "the waters of the Atlantic Ocean" versus, "the waters of [each of] the Great Lakes".

Ghil'ad Zuckermann uses the term superplural to refer to massive plural. He argues that the Australian Aboriginal Barngarla language has four grammatical numbers: singular, dual, plural and superplural.[1]: 227–228 For example:

- wárraidya "emu" (singular)

- wárraidyalbili "two emus" (dual)

- wárraidyarri "emus" (plural)

- wárraidyailyarranha "a lot of emus", "heaps of emus" (superplural)[1]: 228

Formation of plurals[edit]

A given language may make plural forms of nouns by various types of inflection, including the addition of affixes, like the English -(e)s and -ies suffixes, or ablaut, as in the derivation of the plural geese from goose, or a combination of the two. Some languages may also form plurals by reduplication, but not as productive. It may be that some nouns are not marked for plural, like sheep and series in English. In languages which also have a case system, such as Latin and Russian, nouns can have not just one plural form but several, corresponding to the various cases. The inflection might affect multiple words, not just the noun; and the noun itself need not become plural as such, other parts of the expression indicate the plurality.

In English, the most common formation of plural nouns is by adding an -s suffix to the singular noun. (For details and different cases, see English plurals). Just like in English, noun plurals in French, Spanish and Portuguese are also typically formed by adding an -s suffix to the lemma form, sometimes combining it with an additional vowel. (In French, however, this plural suffix is often not pronounced.) This construction is also found in German and Dutch, but only in some nouns. Suffixing is cross-linguistically the most common method of forming plurals.

In Welsh, the reference form, or default quantity, of some nouns is plural, and the singular form is formed from that, eg llygod, mice; llygoden, mouse; erfin, turnips; erfinen, turnip.

Plural forms of other parts of speech[edit]

In many languages, words other than nouns may take plural forms, these being used by way of grammatical agreement with plural nouns (or noun phrases). Such a word may in fact have a number of plural forms, to allow for simultaneous agreement within other categories such as case, person and gender, as well as marking of categories belonging to the word itself (such as tense of verbs, degree of comparison of adjectives, etc.)

Verbs often agree with their subject in number (as well as in person and sometimes gender). Examples of plural forms are the French mangeons, mangez, mangent – respectively the first-, second- and third-person plural of the present tense of the verb manger. In English a distinction is made in the third person between forms such as eats (singular) and eat (plural).

Adjectives may agree with the noun they modify; examples of plural forms are the French petits and petites (the masculine plural and feminine plural respectively of petit). The same applies to some determiners – examples are the French plural definite article les, and the English demonstratives theseand those.

It is common for pronouns, particularly personal pronouns, to have distinct plural forms. Examples in English are we (us, etc.) and they (them etc.; see English personal pronouns), and again these and those (when used as demonstrative pronouns).

In Welsh, a number of common prepositions also inflect to agree with the number, person, and sometimes gender of the noun or pronoun they govern.

Nouns lacking plural or singular form[edit]

Certain nouns do not form plurals. A large class of such nouns in many languages is that of uncountable nouns, representing mass or abstract concepts such as air, information, physics. However, many nouns of this type also have countable meanings or other contexts in which a plural can be used; for example water can take a plural when it means water from a particular source (different waters make for different beers) and in expressions like by the waters of Babylon.

Certain collective nouns do not have a singular form and exist only in the plural, such as "clothes".

There are also nouns found exclusively or almost exclusively in the plural, such as the English scissors. These are referred to with the term plurale tantum. Occasionally, a plural form can pull double duty as the singular form (or vice versa), as has happened with the word "data".

Usage of the plural[edit]

The plural is used, as a rule, for quantities other than one (and other than those quantities represented by other grammatical numbers, such as dual, which a language may possess). Thus it is frequently used with numbers higher than one (two cats, 101 dogs, four and a half hours) and for unspecified amounts of countable things (some men, several cakes, how many lumps?, birds have feathers). The precise rules for the use of plurals, however, depends on the language – for example Russian uses the genitive singular rather than the plural after certain numbers (see above).

Treatments differ in expressions of zero quantity: English often uses the plural in such expressions as no injuries and zero points, although no (and zeroin some contexts) may also take a singular. In French, the singular form is used after zéro.

English also tends to use the plural with decimal fractions, even if less than one, as in 0.3 metres, 0.9 children. Common fractions less than one tend to be used with singular expressions: half (of) a loaf, two-thirds of a mile. Negative numbers are usually treated the same as the corresponding positive ones: minus one degree, minus two degrees. Again, rules on such matters differ between languages.

In some languages, including English, expressions that appear to be singular in form may be treated as plural if they are used with a plural sense, as in the government are agreed. The reverse is also possible: the United States is a powerful country. See synesis, and also English plural § Singulars as plural and plurals as singular.

POS tagging[edit]

In part-of-speech tagging notation, tags are used to distinguish different types of plurals based on their grammatical and semantic context.[2] Resolution varies, for example the Penn-Treebank tagset (~36 tags) has two tags: NNS - noun, plural, and NPS - Proper noun, plural,[3] while the CLAWS 7 tagset (~149 tags)[4] uses six: NN2 - plural common noun, NNL2 - plural locative noun, NNO2 - numeral noun, plural, NNT2 - temporal noun, plural, NNU2 - plural unit of measurement, NP2 - plural proper noun.

No comments:

Post a Comment