Jerry Dyer, Chief of the Fresno Police is set to retire next year. Dyer has been a Fresno police officer since 1980

Ever so brave I say that this is the true,

people come up behind me and pull the end tips of my hair,

I turn to see what is there as if I have caught my hair on something knowing I am far from the wall I just passed,

and lo,

behold there is a person that is actually pulling the end tips of my hair.

I say nothing as my face must say it all,

quickly the person will say,

"can you feel that"?

In a bit of twist I say yes,

the person makes an odd facial expression and goes on about their business,

staring at my head.

How odd people are,

the been since my birth,

those exorcisms from the Religious realms,

the people saying that I'm a psychic.

Yuck I declare as that is just a guessing game playing on past events in a pattern of wreak,

the beast of that messaging should be done by a Cop that just bends light,

a mirror approach.

So simple just that one is as the horizon just repeats,

the riddle is not a puzzle,

the missing piece is just the timeline already completed but not yet found.

Now Computers :),

why on earth would a Man not bend light,

the answer my steward is their not thinking.

Wouldn't that bump,

the Camel would water,

the bucket would not be a wish list,

and a lump of sugar would actually toot sweet.

Science is behind,

people are it's petri,

the dish is served,

half cold the Earth on her sweep,

the glacier gurgles,

water is not oceans of explain,

the body is just the bag that the Universe's friend,

why you may ask as your mind converse,

well it is not a deep subject,

it is because we are human Beings!!

Wouldn't it be weird if the Ocean was a womb,

wouldn't it be weird if it was finally birthing as it does contain life forms,

wouldn't it be weird if that big first ice age thing was simply Outer Space giving Earth an Amniocentesis Test,

wouldn't that be just the strangest thing if the ocean was shoring to expand it's wealth of carriage,

that's so deep.

that's so deep.

hmm....

Amniocentesis

is a medical procedure used in prenatal diagnosis of chromosomal

abnormalities and fetal infections, and also for sex determination, in

which a small amount of amniotic fluid, which contains ... Wikipedia

In philosophy, being refers to the existence of a thing. Anything that exists has being. Ontology is the branch of philosophy that studies being. Being is a concept

Flinders Petrie

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

This article needs additional citations for verification. (January 2016) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

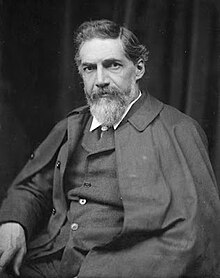

| Flinders Petrie | |

|---|---|

Flinders Petrie, 1903

| |

| Born | William Matthew Flinders Petrie 3 June 1853 Charlton, London, England |

| Died | 28 July 1942 (aged 89) Jerusalem, Mandatory Palestine |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Merneptah Stele, pottery seriation[1] |

| Spouse(s) | Hilda Petrie |

| Awards | Fellow of the Royal Society[2] Huxley Memorial Medal (1906) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Egyptologist |

Flinders Petrie by Philip Alexius de Laszlo, 1934 (detail)

The

distinctive black-topped Egyptian pottery of the PreDynastic period

associated with Flinders Petrie's Sequence Dating System, Petrie Museum

Contents

Early life

Petrie was born on 3 June 1853 in Maryon Road, Charlton, Kent, England, the son of William Petrie (1821–1908) and Anne (née Flinders) (1812–1892). Anne was the daughter of Captain Matthew Flinders, who led the first circumnavigation of Australia. William Petrie was an electrical engineer who developed carbon arc lighting and later developed chemical processes for Johnson, Matthey & Co.[7]Petrie was raised in a Christian household (his father being a member of the Plymouth Brethren), and was educated at home. He had no formal education. His father taught his son how to survey accurately, laying the foundation for his archaeological career. At the age of eight, he was tutored in French, Latin, and Greek, until he had a collapse and was taught at home. He also ventured his first archaeological opinion aged eight, when friends visiting the Petrie family were describing the unearthing of the Brading Roman Villa in the Isle of Wight. The boy was horrified to hear the rough shovelling out of the contents, and protested that the earth should be pared away, inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay.[8] "All that I have done since," he wrote when he was in his late seventies, "was there to begin with, so true it is that we can only develop what is born in the mind. I was already in archaeology by nature."[9]

Academic career

The chair of Edwards Professor of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at University College London was set up and funded in 1892 following a bequest from Amelia Edwards, who died suddenly in that year. Petrie's supporter since 1880, Edwards had instructed that he should be its first incumbent. He continued to excavate in Egypt after taking up the professorship, training many of the best archaeologists of the day.In 1913 Petrie sold his large collection of Egyptian antiquities to University College, London, where it is now housed in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology. One of his trainees, Howard Carter, went on to discover the tomb of Tutankhamun in 1922.

Archaeology career

A photograph Petrie took of his view from the tomb he lived in in Giza 1881

Petrie's published reports of this triangulation survey, and his analysis of the architecture of Giza therein, was exemplary in its methodology and accuracy, disproved Smyth's theories and still provides much of the basic data regarding the pyramid plateau to this day. On that visit, he was appalled by the rate of destruction of monuments (some listed in guidebooks had been worn away completely since then) and mummies. He described Egypt as "a house on fire, so rapid was the destruction" and felt his duty to be that of a "salvage man, to get all I could, as quickly as possible and then, when I was 60, I would sit and write it all."

Returning to England at the end of 1880, Petrie wrote a number of articles and then met Amelia Edwards, journalist and patron of the Egypt Exploration Fund (now the Egypt Exploration Society), who became his strong supporter and later appointed him as Professor at her Egyptology chair at University College London. Impressed by his scientific approach, they offered him work as the successor to Édouard Naville. Petrie accepted the position and was given the sum of £250 per month to cover the excavation's expenses. In November 1884, Petrie arrived in Egypt to begin his excavations.

He first went to a New Kingdom site at Tanis, with 170 workmen. He cut out the middle man role of foreman on this and all subsequent excavations, taking complete overall control himself and removing pressure on the workmen from the foreman to discover finds quickly but sloppily. Though he was regarded as an amateur and dilettante by more established Egyptologists, this made him popular with his workers, who found several small but significant finds that would have been lost under the old system.

The Famine Stela is an inscription located on Sehel Island.

By the end of the Tanis dig, he ran out of funding but, reluctant to leave the country in case it was renewed, he spent 1887 cruising the Nile taking photographs as a less subjective record than sketches. During this time, he also climbed rope ladders at Sehel Island near Aswan to draw and photograph thousands of early Egyptian inscriptions on a cliff face, recording embassies to Nubia, famines and wars. By the time he reached Aswan, a telegram had reached there to confirm the renewal of his funding. He then went straight to the burial site at Fayum, particularly interested in post-30 BC burials, which had not previously been fully studied. He found intact tombs and 60 of the famous portraits, and discovered from inscriptions on the mummies that they were kept with their living families for generations before burial. Under Auguste Mariette's arrangements, he sent 50% of these portraits to the Egyptian department of antiquities.

However, when he later found that Gaston Maspero placed little value on them and left them open to the elements in a yard behind the museum to deteriorate, he angrily demanded that they all be returned, forcing Maspero to pick the 12 best examples for the museum to keep and return 48 to Petrie, who sent them to London for a special showing at the British Museum. Resuming work, he discovered the village of the Pharaonic tomb-workers.

In 1890, Petrie made the first of his many forays into Palestine, leading to much important archaeological work. His six-week excavation of Tell el-Hesi (which was mistakenly identified as Lachish) that year represents the first scientific excavation of an archaeological site in the Holy Land. Petrie surveyed a group of tombs in the Wadi al-Rababah (the biblical Hinnom) of Jerusalem, largely dating to the Iron Age and early Roman periods. Here, in these ancient monuments, Petrie discovered two different metrical systems.

From 1891, he worked on the temple of Aten at Tell-el-Amarna, discovering a 300-square-foot (28 m2) New Kingdom painted pavement of garden and animals and hunting scenes. This became a tourist attraction but, as there was no direct access to the site, tourists wrecked neighbouring fields on their way to it. This made local farmers deface the paintings, and it is only thanks to Petrie's copies that their original appearance is known.

Petrie’s extraordinary visual memory

Mr. Flinders Petrie, a contributor of interesting experiments on kindred subjects to Nature, informs me that he habitually works out sums by aid of an imaginary sliding rule, which he sets in the desired way and reads off mentally.

He does not usually visualise the whole rule, but only that part of it with which he is at the moment concerned.

I think this is one of the most striking cases of accurate visualising power it is possible to imagine.

Francis Galton, (1883).[13]

He does not usually visualise the whole rule, but only that part of it with which he is at the moment concerned.

I think this is one of the most striking cases of accurate visualising power it is possible to imagine.

Francis Galton, (1883).[13]

Discovery of the 'Israel' or Merneptah stele

In early 1896, Petrie and his archaeological team were conducting excavations on a temple in Petrie's area of concession at Luxor.[14] This temple complex was located just north of the original funerary temple of Amenhotep III which had been built on a flood plain.[15] They were initially surprised that this building which they were excavating:- 'was also attributed to Amenophis III since only his name appeared on blocks strewn over the site...Could one king have had two mortuary temples? Petrie dug and soon solved the puzzle: the temple had been built by Merneptah, the son and successor of Ramesses II, almost entirely from stone which had been plundered from the temple of Amenophis III nearby. Statues of the latter had been smashed and the pieces thrown into the foundations; fragments of couchant stone jackals, which must have once formed an imposing avenue approaching the pylon, and broken drums gave some idea of the splendour of the original temple. A statue of Merenptah himself was found—the first known portrait of this king....Better was to follow: two splendid stelae were found,[16] both of them usurped on the reverse side by Merenptah, who had turned them face to the wall. One, beautifully carved, showed Amenophis III in battle with Nubians and Syrians; the other, of black granite, was over ten feet high, larger than any stela previously known; the original text commemorated the building achievements of Amenophis and described the beauties and magnificence of the temple in which it had stood. When it could be turned over an inscription of Merenptah recording his triumphs over the Libyans and the Peoples of the Sea was revealed; [Wilhelm] Spiegelberg [a noted German philologist] came over to read it, and near the end of the text he was puzzled by one, that of a people or tribe whom Merenptah had victoriously smitten-"I.si.ri.ar?" It was Petrie whose quick imaginative mind leapt[t] to the solution: "Israel!" Spiegelberg agreed that it must be so. "Won't the reverends be pleased?" was his comment. At dinner that evening Petrie prophesied: "This stele will be better known in the world than anything else I have found." It was the first mention of the word "Israel" in any Egyptian text and the news made headlines when it reached the English papers.'[15]

Later life

In 1923, Petrie was knighted for services to British archaeology and Egyptology. The focus of his work shifted permanently to Palestine in 1926 (although he did become interested in early Egypt, in 1928 digging a cemetery at Luxor that proved so huge that he devised an entirely new excavation system, including comparison charts for finds, which is still used today). He began excavating several important sites in the south-west of Palestine, including Tell el-Jemmeh and Tell el-Ajjul.In 1933, on retiring from his professorship, he moved permanently to Jerusalem, where he lived with Lady Petrie at the British School of Archaeology, then temporarily headquartered at the American School of Oriental Research (today the W. F. Albright Institute of Archaeological Research).

Death and preservation of head

Petrie's headstone in the Protestant Cemetery, Jerusalem (2009)

Personal life

Petrie married Hilda Urlin (1871–1957) in London on 26 November 1896. The couple had two children, John (1907–1972) and Ann (1909–1989). The family originally lived in Hampstead, where an English Heritage blue plaque has been placed on the building they lived in, 5 Cannon Place.[19] John Flinders Petrie became a noted mathematician, who gave his name to the Petrie polygon.Legacy

Petrie's painstaking recording and study of artifacts set new standards in archaeology. He wrote: "I believe the true line of research lies in the noting and comparison of the smallest details." By linking styles of pottery with periods, he was the first to use seriation in Egyptology, a new method for establishing the chronology of a site. Flinders Petrie was also responsible for mentoring and training a whole generation of Egyptologists, including Howard Carter. After his death, his wife, Hilda Petrie created a student travel scholarship to Egypt on the Centennial of Petrie's birth in 1953.Many thousands of artefacts recovered during excavations led by Petrie can be found in museums worldwide.[20]

Petrie remains a controversial figure for his pro-eugenics views and opinions on other social topics, which spilled over into his disputes with the British Museum's Egyptology expert, E. A. Wallis Budge. Budge's contention that the religion of the Egyptians was essentially identical to the religions of the people of northeastern and central Africa was regarded by his colleagues as impossible, since all but a few followed Petrie in his contention that the culture of Ancient Egypt was derived from an invading Caucasoid "Dynastic Race" which had conquered Egypt in late prehistory and introduced the Pharaonic culture.[21] Petrie was a dedicated follower of eugenics, believing that there was no such thing as cultural or social innovation in human society, but rather that all social change is the result of biological change, such as migration and foreign conquest resulting in interbreeding. Petrie claimed that his "Dynastic Race", in which he never ceased to believe, was a "fine" Caucasoid race that entered Egypt from the south in late predynastic times, conquered the "inferior" and "exhausted" "mulatto" race then inhabiting Egypt, and slowly introduced the finer Dynastic civilisation as they interbred with the inferior indigenous people.[22] Petrie, who was also affiliated with a variety of far right-wing groups and anti-democratic thought in England and was a dedicated believer in the superiority of the Northern peoples over the Latinate and Southern peoples,[22] derided Budge's belief that the ancient Egyptians were an African people with roots in eastern Africa as impossible and "unscientific", as did his followers.

His involvement in Palestinian archaeology was examined in the exhibition "A Future for the Past: Petrie's Palestinian Collection".[23][24]

The Petrie Medal was created in celebration of Petrie's seventieth birthday, when funds were raised to commission and produce 20 medals to be awarded “once in every three years for distinguished work in Archaeology, preferably to a British subject”.[25] The first medal was awarded to Petrie himself (1925), and the first few recipients included Sir Aurel Stein (1928), Sir Arthur Evans (1931), Abbé Henri Breuil (1934), Prof J.D. Beazley (1937), Sir Mortimer Wheeler (1950), Prof J.B. Wace (1953), Sir Leonard Woolley (1957).[26]

Published work

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Flinders Petrie |

- Tel el-Hesy (Lachish). London: Palestine Exploration Fund.

- "The Tomb-Cutter’s Cubits at Jerusalem,” Palestine Exploration Fund Quarterly, 1892 Vol. 24: 24–35.

Contributions to the Encyclopædia Britannica, 11th ed.

- "Abydos (Egypt)". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Egypt". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Pyramid". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

- "Weights and Measures". Encyclopædia Britannica (11th ed.). 1911.

Selected works

- Naukratis, Pt. I, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1886.

- Tanis, Pt. I, Egypt Exploration Fund, 1889.

- Migrations, Anthropological Inst. of Great Britain and Ireland, 1906.

- Janus in Modern Life, G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1907.

- Eastern Exploration – Past and Future London: Constable and Company Ltd., 1918.

- Some Sources of Human History, Society for Promoting Christian Knowledge, 1919.

- The Status of the Jews in Egypt, G. Allen & Unwin, 1922.

- The Revolutions of Civilization, Harper & Brothers, 1922.

Gallery

- Flinders Petrie, by George Frederic Watts, 1900.

- Petrie Exhibiting Material from Tell Fara in London.

- Flinders Petrie, by Ludwig Blum. Painted in Jerusalem in 1937.

References

- Sarah Strong and Helen Wang, “Sir Aurel Stein’s Medals at the Royal Geographical Society”, in Helen Wang (ed.) Sir Aurel Stein, Colleagues and Collections (British Museum Research Publication 184) (2012). https://www.britishmuseum.org/research/publications/research_publications_series/2012/sir_aurel_stein.aspx

Further reading

- Joseph A. Callaway, "Sir Flinders Petrie, Father of Palestinian Archaeology." Biblical Archaeology Review, 1980 Vol. 6, Issue 6: 44–55.

- Margaret S. Drower, Flinders Petrie: A Life in Archaeology, (2nd publication) University of Wisconsin Press, 1995. ISBN 0-299-14624-3

- Margaret S. Drower, Letters from the Desert – the Correspondence of Flinders and Hilda Petrie, Aris & Philips, 2004. ISBN 0-85668-748-0

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie, Seventy Years in Archaeology, H. Holt and Company 1932

- Janet Picton, Stephen Quirke, and Paul C. Roberts (eds), "Living Images: Egyptian Funerary Portraits in the Petrie Museum.” 2007. Left Coast Press, Walnut Creek.

- Schultz, Teresa and Trumpour, Mark, “The Father of Egyptology” in Canada. 2009. Journal of the American Research Centre in Egypt, No. 44, 2008. 159 – 167.

- Stephen Quirke: Hidden Hands, Egyptian workforces in Petrie excavation archives, 1880–1924, London 2010 ISBN 978-0-7156-3904-7

- Silberman, Neil Asher. “Petrie’s Head: Eugenics and Near Eastern Archaeology”, in Alice B. Kehoe and Mary Beth Emmerichs, Assembling the Past (Albuquerque, NM, 1999).

- Stevenson, Alice "'We seem to be working in the same line'. A.H.L.F. Pitt-Rivers and W.M.F. Petrie. Bulletin of the History of Archaeology, 2012 Vol 22, Issue 1: 4–13.

- Trigger, Bruce G. "Paradigms in Sudan Archeology", International Journal of African Historical Studies, vol. 27, no. 2 (1994).

- E.P. Uphill, "A Bibliography of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie (1853–1942)," Journal of Near Eastern Studies, 1972 Vol. 31: 356–379.

External links

| Wikisource has original text related to this article:

|

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flinders Petrie. |

| Library resources about Flinders Petrie |

| By Flinders Petrie |

|---|

- William Matthew Flinders Petrie: The Father of Egyptian Archaeology, 1853–1942

- Works by William Matthew Flinders Petrie at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Flinders Petrie at Internet Archive

- Works by Flinders Petrie at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Flinders Petrie at Open Library

- Flinders Petrie at Goodreads

- Manchester Museum

- Hilda Mary Isobel Petrie born Urlin (1871–1956)

- The Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology in London

Categories:

- 1853 births

- 1942 deaths

- Academics of University College London

- English archaeologists

- English Egyptologists

- English academics

- Knights Bachelor

- English Anglicans

- People from Charlton, London

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Burials at Mount Zion (Protestant)

- 19th-century archaeologists

- 20th-century archaeologists

- Contributors to the Oxford English Dictionary

- Fellows of the British Academy

No comments:

Post a Comment