In mind to the California State of being a drought staff to the land and it's caliber of Lake Tahoe reserves inch the plural masses as water to the mountains in the Winter of our grants, in such an estuary comes to this write as Caltrans the bridge and The Bay!!

To discussion of such the snow on the felt (leopard demonstration for affect as the coat of) while the aspiration of land to the belting of such a grip that Caltrans may cover the trains (style to discover of Trains and Freight) in formal shore to the perforated pipes that gather the clean snow melt. As the Oroville Dam had structure gallery to the scene of 2017 the vista of review should heel the shallow grave of just another wall, that thunder of light rail will only justify the concept of already happened doubling the initial trial to the trail itself. In reserve of a pipeline as demonstrated by the Alaskan Pipeline Project and as SMUD is already above ground in that area of the Valley of Sacramento (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sacramento_Valley) the cause to shift will not offend the operation of what is a blight. In that is the reality of why SMUD is above ground in the very aspect of known to the soaking grounds of all those Rice Fields (http://calrice.org/) subjecting electrical current to a more graceful scale to score.

Simply the Caltrans Men and Women in their wise and creative staff to revolution off the gear of what is in usual may take a blueprint to the board and envelope the cause to the effect of clean snow drift melting, and in-addition partner with the more mountainous regions of our great State and bring avalanche's to a more halting use and the life-saving factor at the ski resorts would certainly improve Insurance revolvers. As that in-turn would copper a mold the prospecting of gold would be found again as the basic to the metal on the heat touching a manmade estuary of substance not being subtle to the whims of Mother Nature and her prowess to demand excellence at her carving of cliff mountain slips as the rock beneath preparing for the deeply sunk water sync to ravage on a future hot summer day.

Bride to simmer as she does balance her own womb to the pregnant fashions of cloud filled cause. In that the avid learner would indeed be shocked by the power of Caltrans in thought on such avid and demanding affairs. Oh how the men of Caltrans ankle my hand to their whisper of the wind on such a sync that I blush in compare for even such a suggest, however, we are in the legs of a world that has provided a venue so that even I, little as I am may place to license and plate a dinner comprehension that dessert may prose.

The financial stride is for the most to the least? No, I know that the foot per dollar is on the pipe as the struck will only formalize an excuse to dump the steer to that whimp of dam that only clatters to the held of just a proposition lake. Measure of the mile with the already ready venue of what has been provided by the Oil Companies has in further brought such a tumbler to the reality of just the computation of what is the cost of a 2x4 (Two-by-four, a common size of dimensional lumber named for its unprocessed dimensions, usually measuring 1½ × 3½ inches in practice) as the log to character is the altitude? No, it is the ask of Caltrans and the admission.

Jan. 27, 2017

Storms Filled 37 Percent of CA Snow-Water Deficit

January storms in the Sierra Nevadas reduced California's deficit in stored snow water by about 37 percent.

Credits: Flickr user Perfect Zero, CC BY 2.0

The "atmospheric river" weather patterns that pummeled California with storms from late December to late January may have recouped 37 percent of the state’s five-year snow-water deficit, according to new University of Colorado Boulder-led research using NASA satellite data.

Researchers at the university's Center for Water Earth Science and Technology (CWEST) estimate that two powerful recent storms deposited roughly 17.5-million acre feet (21.6 cubic kilometers) of water on California’s Sierra Nevada range in January. Compared to averages from the pre-drought satellite record, that amount represents more than 120 percent of the typical annual snow accumulation for this range. Snowmelt from the range is a critical water source for the state's agriculture, hydropower generation and municipal water supplies.

To derive the estimate, the researchers combined data from NASA’s Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) instruments on NASA’s Aqua and Terra spacecraft; a computer model jointly developed by the University of Colorado and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, California; and ground-based snow sensor data from the California Department of Water Resources, Sacramento.

Drainage system (geomorphology)

In geomorphology, drainage systems, also known as river systems, are the patterns formed by the streams, rivers, and lakes in a particular drainage basin. They are governed by the topography of the land, whether a particular region is dominated by hard or soft rocks, and the gradient of the land. Geomorphologists and hydrologists often view streams as being part of drainage basins. A drainage basin is the topographic region from which a stream receives runoff, throughflow, and groundwater flow. The number, size, and shape of the drainage basins found in an area vary and the larger the topographic map, the more information on the drainage basin is available.[1]

Contents

[hide]Drainage patterns[edit]

According to the configuration of the channels, drainage systems can fall into one of several categories known as drainage patterns. Drainage patterns depend on the topography and geology of the land.[2]

Accordant drainage patterns[edit]

A drainage system is described as accordant if its pattern correlates to the structure and relief of the landscape over which it flows.[2]

Dendritic drainage pattern[edit]

Dendritic drainage systems (from Greek δενδρίτης, dendrites, "of or pertaining to a tree") are the most common form of drainage system. In a dendritic system, there are many contributing streams (analogous to the twigs of a tree), which are then joined together into the tributaries of the main river (the branches and the trunk of the tree, respectively). They develop where the river channel follows the slope of the terrain. Dendritic systems form in V-shaped valleys; as a result, the rock types must be impervious and non-porous.[3]

Parallel drainage pattern[edit]

A parallel drainage system is a pattern of rivers caused by steep slopes with some relief. Because of the steep slopes, the streams are swift and straight, with very few tributaries, and all flow in the same direction. This system forms on uniformly sloping surfaces, for example, rivers flowing southeast from the Aberdare Mountains in Kenya.

Parallel drainage patterns form where there is a pronounced slope to the surface. A parallel pattern also develops in regions of parallel, elongate landforms like outcropping resistant rock bands. Tributary streams tend to stretch out in a parallel-like fashion following the slope of the surface. A parallel pattern sometimes indicates the presence of a major fault that cuts across an area of steeply folded bedrock. All forms of transitions can occur between parallel, dendritic, and trellis patterns.

Trellis drainage pattern[edit]

The geometry of a trellis drainage system is similar to that of a common garden trellis used to grow vines. As the river flows along a strike valley, smaller tributaries feed into it from the steep slopes on the sides of mountains. These tributaries enter the main river at approximately 90 degree angle, causing a trellis-like appearance of the drainage system. Trellis drainage is characteristic of folded mountains, such as the Appalachian Mountains in North America and in the north part of Trinidad.[2]

Rectangular drainage pattern[edit]

Rectangular drainage develops on rocks that are of approximately uniform resistance to erosion, but which have two directions of joining at approximately right angles. The joints are usually less resistant to erosion than the bulk rock so erosion tends to preferentially open the joints and streams eventually develop along the joints. The result is a stream system in which streams consist mainly of straight line segments with right angle bends and tributaries join larger streams at right angles.[2]

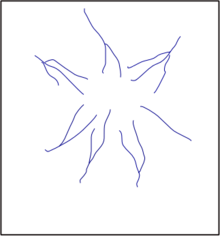

Radial drainage pattern[edit]

In a radial drainage system, the streams radiate outwards from a central high point. Volcanoes usually display excellent radial drainage. Other geological features on which radial drainage commonly develops are domes and laccoliths. On these features the drainage may exhibit a combination of radial patterns.

Centripetal drainage pattern[edit]

The centripetal drainage system is similar to the radial drainage system, with the only exception that radial drainage flows out versus centripetal drainage flows in.

Deranged drainage pattern[edit]

A deranged drainage system is a drainage system in drainage basins where there is no coherent pattern to the rivers and lakes. It happens in areas where there has been much geological disruption. The classic example is the Canadian Shield. During the last ice age, the topsoil was scraped off, leaving mostly bare rock. The melting of the glaciers left land with many irregularities of elevation, and a great deal of water to collect in the low points, explaining the large number of lakes which are found in Canada. The drainage basins are young and are still sorting themselves out. Eventually the system will stabilize.[1]

Annular drainage pattern[edit]

In an annular drainage pattern streams follow a roughly circular or concentric path along a belt of weak rock, resembling in plan a ringlike pattern. It is best displayed by streams draining a maturely dissected structural dome or basin where erosion has exposed rimming sedimentary strata of greatly varying degrees of hardness, as in the Red Valley, which nearly encircles the domal structure of the Black Hills of South Dakota.

Angular drainage pattern[edit]

Angular drainage patterns form where bedrock joints and faults intersect at more acute angles than rectangular drainage patterns. Angles are both more and less than 90 degrees.[4]

Discordant drainage patterns[edit]

A drainage pattern is described as discordant if it does not correlate to the topography and geology of the area. Discordant drainage patterns are classified into two main types: antecedent and superimposed,[2] while anteposition drainage patterns combine the two. In antecedent drainage, a river's vertical incision ability matches that of land uplift due to tectonic forces. Superimposed drainage develops differently: initially, a drainage system develops on a surface composed of 'younger' rocks, but due to denudative activities this surface of younger rocks is removed and the river continues to flow over a seemingly new surface, but one in fact made up of rocks of old geological formation.

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Pidwirny, M., (2006). "The Drainage Basin Concept". Fundamentals of Physical Geography, 2nd Edition.

- ^ a b c d e Ritter, Michael E., The Physical Environment: an Introduction to Physical Geography. 2006

- ^ Lambert, David (1998). The Field Guide to Geology. Checkmark Books. pp. 130–131. ISBN 0-8160-3823-6.

- ^ Easterbrook, Don J (1969). Chapter 7, Origins of Stream Valleys and Drainage Patterns. Principles of Geomorphology. McGraw-Hill Book Company. pp. 148-153. ISBN 0-07-018780-0 (this author defines dendritic, trellis, rectangular, angular, radial, annular, centripetal and parallel drainage patterns)

No comments:

Post a Comment