Cantore arithmetic is not artificial intelligence comma pause breathe breadth it is arithmetic and as such the word signs must be at most to identify the addition and the subtraction in order to divide.

The first to the last at what is what will be reliant on and not with the identified popular news and media vistas. The Loch Ness Monster to the flower that local news reports each time that it has bloomed. The overindulgence on these to it’s place to cantore Arithmetic and opportunity.

Cast to the Loch Ness Monster has found a match at a more real and defining study to land and not mass leaving the idea to the moment of what is what.

The flower in San Francisco at the exhibit in the Golden Gate Park has found a match to the economy of ecology and is or may be environmentally friendly as the current discussion on said subject has been filed worldwide.

To match the lochness up first the cast goes to another pyramid however it retains a square and is a safe place to look and compare as oppose to scratch and sniff a common book as popups also ruled the school at what is that and explanation by those of whom have been educated may have better to opportunity to use and compare to a application of suppose.

To match the flower in Golden Gate Park the subject of a friend of mine since Wallenberg High School in San Francisco, California, cantore arithmetic will refer to Eric Bianco. He is a man that can answer applicable application for the Corpse Flower Worldwide: A real find.

This balance does not have a game of teeter-totter however retains a good effect to sayings, quotes and a given situation that may fascinate the sciences in the future: Cause to coast.

Chichen Itza

Chichén Itzá[nb 1] (often spelled Chichen Itza in English and traditional Yucatec Maya) was a large pre-Columbian city built by the Maya people of the Terminal Classic period. The archeological site is located in Tinúm Municipality, Yucatán State, Mexico.[1]

Chichén Itzá was a major focal point in the Northern Maya Lowlands from the Late Classic (c. AD 600–900) through the Terminal Classic (c. AD 800–900) and into the early portion of the Postclassic period (c. AD 900–1200). The site exhibits a multitude of architectural styles, reminiscent of styles seen in central Mexico and of the Puuc and Chenes styles of the Northern Maya lowlands. The presence of central Mexican styles was once thought to have been representative of direct migration or even conquest from central Mexico, but most contemporary interpretations view the presence of these non-Maya styles more as the result of cultural diffusion.

Chichén Itzá was one of the largest Maya cities and it was likely to have been one of the mythical great cities, or Tollans, referred to in later Mesoamerican literature.[2] The city may have had the most diverse population in the Maya world, a factor that could have contributed to the variety of architectural styles at the site.[3]

The ruins of Chichén Itzá are federal property, and the site's stewardship is maintained by Mexico's Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (National Institute of Anthropology and History). The land under the monuments had been privately owned until 29 March 2010, when it was purchased by the state of Yucatán.[nb 2]

Chichén Itzá is one of the most visited archeological sites in Mexico with over 2.6 million tourists in 2017.[4]

Name and orthography

The Maya name "Chichen Itza" means "At the mouth of the well of the Itza." This derives from chi', meaning "mouth" or "edge", and chʼen or chʼeʼen, meaning "well". Itzá is the name of an ethnic-lineage group that gained political and economic dominance of the northern peninsula. One possible translation for Itza is "enchanter (or enchantment) of the water,"[5] from its (itz), "sorcerer", and ha, "water".[6]

The name is spelled Chichén Itzá in Spanish, and the accents are sometimes maintained in other languages to show that both parts of the name are stressed on their final syllable. Other references prefer the modern Maya orthography, Chichʼen Itzaʼ (pronounced [tʃitʃʼen itsáʔ]). This form preserves the phonemic distinction between chʼ and ch, since the base word chʼeʼen (which, however, is not stressed in Maya) begins with a postalveolar ejective affricate consonant. Traditional Yucatec Maya spelling in Latin letters, used from the 16th through mid 20th century, spelled it as "Chichen Itza" (as accents on the last syllable are usual for the language, they are not indicated as they are in Spanish). The word "Itzaʼ" has a high tone on the "a" followed by a glottal stop (indicated by the apostrophe).[citation needed]

Evidence in the Chilam Balam books indicates another, earlier name for this city prior to the arrival of the Itza hegemony in northern Yucatán. While most sources agree the first word means seven, there is considerable debate as to the correct translation of the rest. This earlier name is difficult to define because of the absence of a single standard of orthography, but it is represented variously as Uuc Yabnal ("Seven Great House"),[7] Uuc Hab Nal ("Seven Bushy Places"),[8] Uucyabnal ("Seven Great Rulers")[2] or Uc Abnal ("Seven Lines of Abnal").[nb 3]This name, dating to the Late Classic Period, is recorded both in the book of Chilam Balam de Chumayel and in hieroglyphic texts in the ruins.[9]

Location

Chichén Itzá is located in the eastern portion of Yucatán state in Mexico.[10] The northern Yucatán Peninsula is karst, and the rivers in the interior all run underground. There are four visible, natural sink holes, called cenotes, that could have provided plentiful water year round at Chichen, making it attractive for settlement. Of these cenotes, the "Cenote Sagrado" or "Sacred Cenote" (also variously known as the Sacred Well or Well of Sacrifice), is the most famous.[11] In 2015, scientists determined that there is a hidden cenote under the Temple of Kukulkan, which has never been seen by archeologists.[12]

According to post-Conquest sources (Maya and Spanish), pre-Columbian Maya sacrificed objects and human beings into the cenote as a form of worship to the Maya rain god Chaac. Edward Herbert Thompson dredged the Cenote Sagrado from 1904 to 1910, and recovered artifacts of gold, jade, pottery and incense, as well as human remains.[11] A study of human remains taken from the Cenote Sagrado found that they had wounds consistent with human sacrifice.[13]

Political organization

Several archeologists in the late 1980s suggested that unlike previous Maya polities of the Early Classic, Chichén Itzá may not have been governed by an individual ruler or a single dynastic lineage. Instead, the city's political organization could have been structured by a "multepal" system, which is characterized as rulership through council composed of members of elite ruling lineages.[14]

This theory was popular in the 1990s, but in recent years, the research that supported the concept of the "multepal" system has been called into question, if not discredited. The current belief trend in Maya scholarship is toward the more traditional model of the Maya kingdoms of the Classic Period southern lowlands in Mexico.[15]

Economy

Chichén Itzá was a major economic power in the northern Maya lowlands during its apogee.[16] Participating in the water-borne circum-peninsular trade route through its port site of Isla Cerritos on the north coast,[17] Chichen Itza was able to obtain locally unavailable resources from distant areas such as obsidian from central Mexico and gold from southern Central America.

Between AD 900 and 1050 Chichen Itza expanded to become a powerful regional capital controlling north and central Yucatán. It established Isla Cerritos as a trading port.[18]

History

The layout of Chichén Itzá site core developed during its earlier phase of occupation, between 750 and 900 AD.[19]Its final layout was developed after 900 AD, and the 10th century saw the rise of the city as a regional capital controlling the area from central Yucatán to the north coast, with its power extending down the east and west coasts of the peninsula.[20] The earliest hieroglyphic date discovered at Chichen Itza is equivalent to 832 AD, while the last known date was recorded in the Osario temple in 998.[21]

Establishment

The Late Classic city was centered upon the area to the southwest of the Xtoloc cenote, with the main architecture represented by the substructures now underlying the Las Monjas and Observatorio and the basal platform upon which they were built.[22]

Ascendancy

Chichén Itzá rose to regional prominence toward the end of the Early Classic period (roughly 600 AD). It was, however, toward the end of the Late Classic and into the early part of the Terminal Classic that the site became a major regional capital, centralizing and dominating political, sociocultural, economic, and ideological life in the northern Maya lowlands. The ascension of Chichen Itza roughly correlates with the decline and fragmentation of the major centers of the southern Maya lowlands.

As Chichén Itzá rose to prominence, the cities of Yaxuna (to the south) and Coba (to the east) were suffering decline. These two cities had been mutual allies, with Yaxuna dependent upon Coba. At some point in the 10th century Coba lost a significant portion of its territory, isolating Yaxuna, and Chichen Itza may have directly contributed to the collapse of both cities.[23]

Decline

Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo) is the most famous of the buildings in the archeological site | |

Location within Mesoamerica | |

| Location | Yucatán, Mexico |

|---|---|

| Region | Yucatán |

| Coordinates |  20°40′59″N 88°34′7″W 20°40′59″N 88°34′7″W |

| History | |

| Periods | Late Classic to Early Postclassic |

| Cultures | Maya civilization |

| Official name | Pre-Hispanic City of Chichen-Itza |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iii |

| Designated | 1988 (12th session) |

| Reference no. | 483 |

| Region | Latin America and the Caribbean |

According to some colonial Mayan sources (e.g., the Book of Chilam Balam of Chumayel), Hunac Ceel, ruler of Mayapan, conquered Chichen Itza in the 13th century. Hunac Ceel supposedly prophesied his own rise to power. According to custom at the time, individuals thrown into the Cenote Sagrado were believed to have the power of prophecy if they survived. During one such ceremony, the chronicles state, there were no survivors, so Hunac Ceel leaped into the Cenote Sagrado, and when removed, prophesied his own ascension.

While there is some archeological evidence that indicates Chichén Itzá was at one time looted and sacked,[24] there appears to be greater evidence that it could not have been by Mayapan, at least not when Chichén Itzá was an active urban center. Archeological data now indicates that Chichen Itza declined as a regional center by 1100, before the rise of Mayapan. Ongoing research at the site of Mayapan may help resolve this chronological conundrum.

After Chichén Itzá elite activities ceased, the city may not have been abandoned. When the Spanish arrived, they found a thriving local population, although it is not clear from Spanish sources if these Maya were living in Chichen Itza proper, or a nearby settlement. The relatively high population density in the region was a factor in the conquistadors' decision to locate a capital there.[25] According to post-Conquest sources, both Spanish and Maya, the Cenote Sagrado remained a place of pilgrimage.[26]

Spanish conquest

In 1526, Spanish Conquistador Francisco de Montejo (a veteran of the Grijalva and Cortés expeditions) successfully petitioned the King of Spain for a charter to conquer Yucatán. His first campaign in 1527, which covered much of the Yucatán Peninsula, decimated his forces but ended with the establishment of a small fort at Xaman Haʼ, south of what is today Cancún. Montejo returned to Yucatán in 1531 with reinforcements and established his main base at Campeche on the west coast.[27] He sent his son, Francisco Montejo The Younger, in late 1532 to conquer the interior of the Yucatán Peninsula from the north. The objective from the beginning was to go to Chichén Itzá and establish a capital.[28]

Montejo the Younger eventually arrived at Chichén Itzá, which he renamed Ciudad Real. At first he encountered no resistance, and set about dividing the lands around the city and awarding them to his soldiers. The Maya became more hostile over time, and eventually they laid siege to the Spanish, cutting off their supply line to the coast, and forcing them to barricade themselves among the ruins of the ancient city. Months passed, but no reinforcements arrived. Montejo the Younger attempted an all-out assault against the Maya and lost 150 of his remaining troops. He was forced to abandon Chichén Itzá in 1534 under cover of darkness. By 1535, all Spanish had been driven from the Yucatán Peninsula.[29]

Montejo eventually returned to Yucatán and, by recruiting Maya from Campeche and Champoton, built a large Indio-Spanish army and conquered the peninsula.[30] The Spanish crown later issued a land grant that included Chichen Itza and by 1588 it was a working cattle ranch.[31]

Modern history

Chichén Itzá entered the popular imagination in 1843 with the book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan by John Lloyd Stephens (with illustrations by Frederick Catherwood). The book recounted Stephens' visit to Yucatán and his tour of Maya cities, including Chichén Itzá. The book prompted other explorations of the city. In 1860, Désiré Charnaysurveyed Chichén Itzá and took numerous photographs that he published in Cités et ruines américaines (1863).

Visitors to Chichén Itzá during the 1870s and 1880s came with photographic equipment and recorded more accurately the condition of several buildings.[32] In 1875, Augustus Le Plongeon and his wife Alice Dixon Le Plongeon visited Chichén, and excavated a statue of a figure on its back, knees drawn up, upper torso raised on its elbows with a plate on its stomach. Augustus Le Plongeon called it "Chaacmol" (later renamed "Chac Mool", which has been the term to describe all types of this statuary found in Mesoamerica). Teobert Maler and Alfred Maudslay explored Chichén in the 1880s and both spent several weeks at the site and took extensive photographs. Maudslay published the first long-form description of Chichen Itza in his book, Biologia Centrali-Americana.

In 1894 the United States Consul to Yucatán, Edward Herbert Thompson, purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included the ruins of Chichen Itza. For 30 years, Thompson explored the ancient city. His discoveries included the earliest dated carving upon a lintel in the Temple of the Initial Series and the excavation of several graves in the Osario (High Priest's Temple). Thompson is most famous for dredging the Cenote Sagrado (Sacred Cenote) from 1904 to 1910, where he recovered artifacts of gold, copper and carved jade, as well as the first-ever examples of what were believed to be pre-Columbian Maya cloth and wooden weapons. Thompson shipped the bulk of the artifacts to the Peabody Museum at Harvard University.

In 1913, the Carnegie Institution accepted the proposal of archeologist Sylvanus G. Morley and committed to conduct long-term archeological research at Chichen Itza.[33] The Mexican Revolution and the following government instability, as well as World War I, delayed the project by a decade.[34]

In 1923, the Mexican government awarded the Carnegie Institution a 10-year permit (later extended another 10 years) to allow U.S. archeologists to conduct extensive excavation and restoration of Chichen Itza.[35] Carnegie researchers excavated and restored the Temple of Warriors and the Caracol, among other major buildings. At the same time, the Mexican government excavated and restored El Castillo (Temple of Kukulcán) and the Great Ball Court.[36]

In 1926, the Mexican government charged Edward Thompson with theft, claiming he stole the artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado and smuggled them out of the country. The government seized the Hacienda Chichén. Thompson, who was in the United States at the time, never returned to Yucatán. He wrote about his research and investigations of the Maya culture in a book People of the Serpent published in 1932. He died in New Jersey in 1935. In 1944 the Mexican Supreme Court ruled that Thompson had broken no laws and returned Chichen Itza to his heirs. The Thompsons sold the hacienda to tourism pioneer Fernando Barbachano Peon.[37]

There have been two later expeditions to recover artifacts from the Cenote Sagrado, in 1961 and 1967. The first was sponsored by the National Geographic, and the second by private interests. Both projects were supervised by Mexico's National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH). INAH has conducted an ongoing effort to excavate and restore other monuments in the archeological zone, including the Osario, Akab Dzib, and several buildings in Chichén Viejo (Old Chichen).

In 2009, to investigate construction that predated El Castillo, Yucatec archeologists began excavations adjacent to El Castillo under the direction of Rafael (Rach) Cobos.

Site description

Chichen Itza was one of the largest Maya cities, with the relatively densely clustered architecture of the site core covering an area of at least 5 square kilometers (1.9 sq mi).[2] Smaller scale residential architecture extends for an unknown distance beyond this.[2] The city was built upon broken terrain, which was artificially levelled in order to build the major architectural groups, with the greatest effort being expended in the levelling of the areas for the Castillo pyramid, and the Las Monjas, Osario and Main Southwest groups.[10]

The site contains many fine stone buildings in various states of preservation, and many have been restored. The buildings were connected by a dense network of paved causeways, called sacbeob.[nb 4] Archeologists have identified over 80 sacbeob criss-crossing the site,[10] and extending in all directions from the city.[38] Many of these stone buildings were originally painted in red, green, blue and purple colors. Pigments were chosen according to what was most easily available in the area. The site must be imagined as a colorful one, not like it is today. Just like Gothic cathedrals in Europe, colors provided a greater sense of completeness and contributed greatly to the symbolic impact of the buildings.[39]

The architecture encompasses a number of styles, including the Puuc and Chenes styles of the northern Yucatán Peninsula.[2] The buildings of Chichen Itza are grouped in a series of architectonic sets, and each set was at one time separated from the other by a series of low walls. The three best known of these complexes are the Great North Platform, which includes the monuments of the Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo), Temple of Warriors and the Great Ball Court; The Osario Group, which includes the pyramid of the same name as well as the Temple of Xtoloc; and the Central Group, which includes the Caracol, Las Monjas, and Akab Dzib.

South of Las Monjas, in an area known as Chichén Viejo (Old Chichén) and only open to archeologists, are several other complexes, such as the Group of the Initial Series, Group of the Lintels, and Group of the Old Castle.

Architectural styles

The Puuc-style architecture is concentrated in the Old Chichen area, and also the earlier structures in the Nunnery Group (including the Las Monjas, Annex and La Iglesia buildings); it is also represented in the Akab Dzib structure.[40] The Puuc-style building feature the usual mosaic-decorated upper façades characteristic of the style but differ from the architecture of the Puuc heartland in their block masonry walls, as opposed to the fine veneers of the Puuc region proper.[41]

At least one structure in the Las Monjas Group features an ornate façade and masked doorway that are typical examples of Chenes-style architecture, a style centered upon a region in the north of Campeche state, lying between the Puuc and Río Bec regions.[42][43]

Those structures with sculpted hieroglyphic script are concentrated in certain areas of the site, with the most important being the Las Monjas group.[21]

Architectural groups

Great North Platform

Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo)

Dominating the North Platform of Chichen Itza is the Temple of Kukulcán (a Maya feathered serpent deity similar to the Aztec Quetzalcoatl). The temple was identified by the first Spaniards to see it, as El Castillo ("the castle"), and it regularly is referred to as such.[44] This step pyramid stands about 30 meters (98 ft) high and consists of a series of nine square terraces, each approximately 2.57 meters (8.4 ft) high, with a 6-meter (20 ft) high temple upon the summit.[45]

The sides of the pyramid are approximately 55.3 meters (181 ft) at the base and rise at an angle of 53°, although that varies slightly for each side.[45] The four faces of the pyramid have protruding stairways that rise at an angle of 45°.[45] The talud walls of each terrace slant at an angle of between 72° and 74°.[45] At the base of the balustrades of the northeastern staircase are carved heads of a serpent.[46]

Mesoamerican cultures periodically superimposed larger structures over older ones,[47] and the Temple of Kukulcán is one such example.[48] In the mid-1930s, the Mexican government sponsored an excavation of the temple. After several false starts, they discovered a staircase under the north side of the pyramid. By digging from the top, they found another temple buried below the current one.[49]

Inside the temple chamber was a Chac Mool statue and a throne in the shape of Jaguar, painted red and with spots made of inlaid jade.[49] The Mexican government excavated a tunnel from the base of the north staircase, up the earlier pyramid's stairway to the hidden temple, and opened it to tourists. In 2006, INAH closed the throne room to the public.[50]

Around the Spring and Autumn equinoxes, in the late afternoon, the northwest corner of the pyramid casts a series of triangular shadows against the western balustrade on the north side that evokes the appearance of a serpent wriggling down the staircase, which some scholars have suggested is a representation of the feathered-serpent deity, Kukulcán.[51] It is a widespread belief that this light-and-shadow effect was achieved on purpose to record the equinoxes, but the idea is highly unlikely: it has been shown that the phenomenon can be observed, without major changes, during several weeks around the equinoxes, making it impossible to determine any date by observing this effect alone.[52]

Great Ball Court

Archeologists have identified in Chichen Itza thirteen ballcourts for playing the Mesoamerican ballgame,[53] but the Great Ball Court about 150 meters (490 ft) to the north-west of the Castillo is the most impressive. It is the largest and best preserved ball court in ancient Mesoamerica.[44] It measures 168 by 70 meters (551 by 230 ft).[54]

The parallel platforms flanking the main playing area are each 95 meters (312 ft) long.[54] The walls of these platforms stand 8 meters (26 ft) high;[54] set high up in the center of each of these walls are rings carved with intertwined feathered serpents.[54][nb 5]

At the base of the high interior walls are slanted benches with sculpted panels of teams of ball players.[44] In one panel, one of the players has been decapitated; the wound emits streams of blood in the form of wriggling snakes.[55]

At one end of the Great Ball Court is the North Temple, also known as the Temple of the Bearded Man (Templo del Hombre Barbado).[56] This small masonry building has detailed bas relief carving on the inner walls, including a center figure that has carving under his chin that resembles facial hair.[57] At the south end is another, much bigger temple, but in ruins.

Built into the east wall are the Temples of the Jaguar. The Upper Temple of the Jaguar overlooks the ball court and has an entrance guarded by two, large columns carved in the familiar feathered serpent motif. Inside there is a large mural, much destroyed, which depicts a battle scene.

In the entrance to the Lower Temple of the Jaguar, which opens behind the ball court, is another Jaguar throne, similar to the one in the inner temple of El Castillo, except that it is well worn and missing paint or other decoration. The outer columns and the walls inside the temple are covered with elaborate bas-relief carvings.

Additional structures

The Tzompantli, or Skull Platform (Plataforma de los Cráneos), shows the clear cultural influence of the central Mexican Plateau. Unlike the tzompantli of the highlands, however, the skulls were impaled vertically rather than horizontally as at Tenochtitlan.[44]

The Platform of the Eagles and the Jaguars (Plataforma de Águilas y Jaguares) is immediately to the east of the Great Ballcourt.[56] It is built in a combination Maya and Toltec styles, with a staircase ascending each of its four sides.[44] The sides are decorated with panels depicting eagles and jaguars consuming human hearts.[44]

This Platform of Venus is dedicated to the planet Venus.[44] In its interior archeologists discovered a collection of large cones carved out of stone,[44] the purpose of which is unknown. This platform is located north of El Castillo, between it and the Cenote Sagrado.[56]

The Temple of the Tables is the northernmost of a series of buildings to the east of El Castillo. Its name comes from a series of altars at the top of the structure that are supported by small carved figures of men with upraised arms, called "atlantes."

The Steam Bath is a unique building with three parts: a waiting gallery, a water bath, and a steam chamber that operated by means of heated stones.

Sacbe Number One is a causeway that leads to the Cenote Sagrado, is the largest and most elaborate at Chichen Itza. This "white road" is 270 meters (890 ft) long with an average width of 9 meters (30 ft). It begins at a low wall a few meters from the Platform of Venus. According to archeologists there once was an extensive building with columns at the beginning of the road.

Sacred Cenote

The Yucatán Peninsula is a limestone plain, with no rivers or streams. The region is pockmarked with natural sinkholes, called cenotes, which expose the water table to the surface. One of the most impressive of these is the Cenote Sagrado, which is 60 meters (200 ft) in diameter[58] and surrounded by sheer cliffs that drop to the water table some 27 meters (89 ft) below.

The Cenote Sagrado was a place of pilgrimage for ancient Maya people who, according to ethnohistoric sources, would conduct sacrifices during times of drought.[58] Archeological investigations support this as thousands of objects have been removed from the bottom of the cenote, including material such as gold, carved jade, copal, pottery, flint, obsidian, shell, wood, rubber, cloth, as well as skeletons of children and men.[58][59]

Temple of the Warriors

The Temple of the Warriors complex consists of a large stepped pyramid fronted and flanked by rows of carved columns depicting warriors. This complex is analogous to Temple B at the Toltec capital of Tula, and indicates some form of cultural contact between the two regions. The one at Chichen Itza, however, was constructed on a larger scale. At the top of the stairway on the pyramid's summit (and leading toward the entrance of the pyramid's temple) is a Chac Mool.

This temple encases or entombs a former structure called The Temple of the Chac Mool. The archeological expedition and restoration of this building was done by the Carnegie Institution of Washington from 1925 to 1928. A key member of this restoration was Earl H. Morris, who published the work from this expedition in two volumes entitled Temple of the Warriors. Watercolors were made of murals in the Temple of the Warriors that were deteriorating rapidly following exposure to the elements after enduring for centuries in the protected enclosures being discovered. Many depict battle scenes and some even have tantalizing images that lend themselves to speculation and debate by prominent Maya scholars, such as Michael D. Coe and Mary Miller, regarding possible contact with Viking sailors.[60]

Group of a Thousand Columns

Along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors are a series of what are today exposed columns, although when the city was inhabited these would have supported an extensive roof system. The columns are in three distinct sections: A west group, that extends the lines of the front of the Temple of Warriors. A north group runs along the south wall of the Temple of Warriors and contains pillars with carvings of soldiers in bas-relief;

A northeast group, which apparently formed a small temple at the southeast corner of the Temple of Warriors, contains a rectangular decorated with carvings of people or gods, as well as animals and serpents. The northeast column temple also covers a small marvel of engineering, a channel that funnels all the rainwater from the complex some 40 meters (130 ft) away to a rejollada, a former cenote.

To the south of the Group of a Thousand Columns is a group of three, smaller, interconnected buildings. The Temple of the Carved Columns is a small elegant building that consists of a front gallery with an inner corridor that leads to an altar with a Chac Mool. There are also numerous columns with rich, bas-relief carvings of some 40 personages.

A section of the upper façade with a motif of x's and o's is displayed in front of the structure. The Temple of the Small Tables which is an unrestored mound. And the Thompson's Temple (referred to in some sources as Palace of Ahau Balam Kauil ), a small building with two levels that has friezes depicting Jaguars (balam in Maya) as well as glyphs of the Maya god Kahuil.

El Mercado

This square structure anchors the southern end of the Temple of Warriors complex. It is so named for the shelf of stone that surrounds a large gallery and patio that early explorers theorized was used to display wares as in a marketplace. Today, archeologists believe that its purpose was more ceremonial than commercial.

Osario Group

South of the North Group is a smaller platform that has many important structures, several of which appear to be oriented toward the second largest cenote at Chichen Itza, Xtoloc.

The Osario itself, like the Temple of Kukulkan, is a step-pyramid temple dominating its platform, only on a smaller scale. Like its larger neighbor, it has four sides with staircases on each side. There is a temple on top, but unlike Kukulkan, at the center is an opening into the pyramid that leads to a natural cave 12 meters (39 ft) below. Edward H. Thompson excavated this cave in the late 19th century, and because he found several skeletons and artifacts such as jade beads, he named the structure The High Priests' Temple. Archeologists today believe neither that the structure was a tomb nor that the personages buried in it were priests.

The Temple of Xtoloc is a recently restored temple outside the Osario Platform is. It overlooks the other large cenote at Chichen Itza, named after the Maya word for iguana, "Xtoloc." The temple contains a series of pilasters carved with images of people, as well as representations of plants, birds, and mythological scenes.

Between the Xtoloc temple and the Osario are several aligned structures: The Platform of Venus, which is similar in design to the structure of the same name next to Kukulkan (El Castillo), the Platform of the Tombs, and a small, round structure that is unnamed. These three structures were constructed in a row extending from the Osario. Beyond them the Osario platform terminates in a wall, which contains an opening to a sacbe that runs several hundred feet to the Xtoloc temple.

South of the Osario, at the boundary of the platform, there are two small buildings that archeologists believe were residences for important personages. These have been named as the House of the Metates and the House of the Mestizas.

Casa Colorada Group

South of the Osario Group is another small platform that has several structures that are among the oldest in the Chichen Itza archeological zone.

The Casa Colorada (Spanish for "Red House") is one of the best preserved buildings at Chichen Itza. Significant red paint was still present in the days of the 19th century explorers. Its Maya name is Chichanchob, which according to INAH may mean "small holes". In one chamber there are extensive carved hieroglyphs that mention rulers of Chichen Itza and possibly of the nearby city of Ek Balam, and contain a Maya date inscribed which correlates to 869 AD, one of the oldest such dates found in all of Chichen Itza.

In 2009, INAH restored a small ball court that adjoined the back wall of the Casa Colorada.[61]

While the Casa Colorada is in a good state of preservation, other buildings in the group, with one exception, are decrepit mounds. One building is half standing, named La Casa del Venado (House of the Deer). This building's name has been long used by the local Maya, and some authors mention that it was named after a deer painting over stucco that doesn't exist anymore.[62]

Central Group

Las Monjas is one of the more notable structures at Chichen Itza. It is a complex of Terminal Classic buildings constructed in the Puuc architectural style. The Spanish named this complex Las Monjas ("The Nuns" or "The Nunnery"), but it was a governmental palace. Just to the east is a small temple (known as the La Iglesia, "The Church") decorated with elaborate masks.[44][63]

The Las Monjas group is distinguished by its concentration of hieroglyphic texts dating to the Late to Terminal Classic. These texts frequently mention a ruler by the name of Kʼakʼupakal.[21][64]

El Caracol ("The Snail") is located to the north of Las Monjas. It is a round building on a large square platform. It gets its name from the stone spiral staircase inside. The structure, with its unusual placement on the platform and its round shape (the others are rectangular, in keeping with Maya practice), is theorized to have been a proto-observatory with doors and windows aligned to astronomical events, specifically around the path of Venus as it traverses the heavens.[65]

Akab Dzib is located to the east of the Caracol. The name means, in Yucatec Mayan, "Dark Writing"; "dark" in the sense of "mysterious". An earlier name of the building, according to a translation of glyphs in the Casa Colorada, is Wa(k)wak Puh Ak Na, "the flat house with the excessive number of chambers", and it was the home of the administrator of Chichén Itzá, kokom Yahawal Choʼ Kʼakʼ.[66]

INAH completed a restoration of the building in 2007. It is relatively short, only 6 meters (20 ft) high, and is 50 meters (160 ft) in length and 15 meters (49 ft) wide. The long, western-facing façade has seven doorways. The eastern façade has only four doorways, broken by a large staircase that leads to the roof. This apparently was the front of the structure, and looks out over what is today a steep, dry, cenote.

The southern end of the building has one entrance. The door opens into a small chamber and on the opposite wall is another doorway, above which on the lintel are intricately carved glyphs—the "mysterious" or "obscure" writing that gives the building its name today. Under the lintel in the doorjamb is another carved panel of a seated figure surrounded by more glyphs. Inside one of the chambers, near the ceiling, is a painted hand print.

Old Chichen

Old Chichen (or Chichén Viejo in Spanish) is the name given to a group of structures to the south of the central site, where most of the Puuc-style architecture of the city is concentrated.[2] It includes the Initial Series Group, the Phallic Temple, the Platform of the Great Turtle, the Temple of the Owls, and the Temple of the Monkeys.

This section of the site has been closed to tourism for years while archaeological excavations and restorations were ongoing, and is planned to reopen to visitors in 2024. [67]

Other structures

Chichen Itza also has a variety of other structures densely packed in the ceremonial center of about 5 square kilometers (1.9 sq mi) and several outlying subsidiary sites.

Caves of Balankanche

Approximately 4 km (2.5 mi) south east of the Chichen Itza archeological zone are a network of sacred caves known as Balankanche (Spanish: Gruta de Balankanche), Balamkaʼancheʼ in Yucatec Maya). In the caves, a large selection of ancient pottery and idols may be seen still in the positions where they were left in pre-Columbian times.

The location of the cave has been well known in modern times. Edward Thompson and Alfred Tozzer visited it in 1905. A.S. Pearse and a team of biologists explored the cave in 1932 and 1936. E. Wyllys Andrews IV also explored the cave in the 1930s. Edwin Shook and R.E. Smith explored the cave on behalf of the Carnegie Institution in 1954, and dug several trenches to recover potsherds and other artifacts. Shook determined that the cave had been inhabited over a long period, at least from the Preclassic to the post-conquest era.[68]

On 15 September 1959, José Humberto Gómez, a local guide, discovered a false wall in the cave. Behind it he found an extended network of caves with significant quantities of undisturbed archeological remains, including pottery and stone-carved censers, stone implements and jewelry. INAH converted the cave into an underground museum, and the objects after being catalogued were returned to their original place so visitors can see them in situ.[69]

Tourism

Chichen Itza is one of the most visited archeological sites in Mexico; in 2017 it was estimated to have received 2.1 million visitors.[70]

Tourism has been a factor at Chichen Itza for more than a century. John Lloyd Stephens, who popularized the Maya Yucatán in the public's imagination with his book Incidents of Travel in Yucatan, inspired many to make a pilgrimage to Chichén Itzá. Even before the book was published, Benjamin Norman and Baron Emanuel von Friedrichsthal traveled to Chichen after meeting Stephens, and both published the results of what they found. Friedrichsthal was the first to photograph Chichen Itza, using the recently invented daguerreotype.[71]

After Edward Thompson in 1894 purchased the Hacienda Chichén, which included Chichen Itza, he received a constant stream of visitors. In 1910 he announced his intention to construct a hotel on his property, but abandoned those plans, probably because of the Mexican Revolution.

In the early 1920s, a group of Yucatecans, led by writer/photographer Francisco Gomez Rul, began working toward expanding tourism to Yucatán. They urged Governor Felipe Carrillo Puerto to build roads to the more famous monuments, including Chichen Itza. In 1923, Governor Carrillo Puerto officially opened the highway to Chichen Itza. Gomez Rul published one of the first guidebooks to Yucatán and the ruins.

Gomez Rul's son-in-law, Fernando Barbachano Peon (a grandnephew of former Yucatán Governor Miguel Barbachano), started Yucatán's first official tourism business in the early 1920s. He began by meeting passengers who arrived by steamship at Progreso, the port north of Mérida, and persuading them to spend a week in Yucatán, after which they would catch the next steamship to their next destination. In his first year Barbachano Peon reportedly was only able to convince seven passengers to leave the ship and join him on a tour. In the mid-1920s Barbachano Peon persuaded Edward Thompson to sell 5 acres (20,000 m2) next to Chichen for a hotel. In 1930, the Mayaland Hotel opened, just north of the Hacienda Chichén, which had been taken over by the Carnegie Institution.[72]

In 1944, Barbachano Peon purchased all of the Hacienda Chichén, including Chichen Itza, from the heirs of Edward Thompson.[37] Around that same time the Carnegie Institution completed its work at Chichen Itza and abandoned the Hacienda Chichén, which Barbachano turned into another seasonal hotel.

In 1972, Mexico enacted the Ley Federal Sobre Monumentos y Zonas Arqueológicas, Artísticas e Históricas (Federal Law over Monuments and Archeological, Artistic and Historic Sites) that put all the nation's pre-Columbian monuments, including those at Chichen Itza, under federal ownership.[73]There were now hundreds, if not thousands, of visitors every year to Chichen Itza, and more were expected with the development of the Cancún resort area to the east.

In the 1980s, Chichen Itza began to receive an influx of visitors on the day of the spring equinox. Today several thousand show up to see the light-and-shadow effect on the Temple of Kukulcán during which the feathered serpent appears to crawl down the side of the pyramid.[nb 6] Tour guides will also demonstrate a unique the acoustical effect at Chichen Itza: a handclap before the staircase of the El Castillo pyramid will produce by an echo that resembles the chirp of a bird, similar to that of the quetzal as investigated by Declercq.[74]

Chichen Itza, a UNESCO World Heritage Site, is the second-most visited of Mexico's archeological sites.[75] The archeological site draws many visitors from the popular tourist resort of Cancún, who make a day trip on tour buses.

In 2007, Chichen Itza's Temple of Kukulcán (El Castillo) was named one of the New Seven Wonders of the World after a worldwide vote. Despite the fact that the vote was sponsored by a commercial enterprise, and that its methodology was criticized, the vote was embraced by government and tourism officials in Mexico who projected that as a result of the publicity the number of tourists to Chichen would double by 2012.[nb 7][76] The ensuing publicity re-ignited debate in Mexico over the ownership of the site, which culminated on 29 March 2010 when the state of Yucatán purchased the land upon which the most recognized monuments rest from owner Hans Juergen Thies Barbachano.[77]

INAH, which manages the site, has closed a number of monuments to public access. While visitors can walk around them, they can no longer climb them or go inside their chambers. Climbing access to El Castillo was closed after a San Diego, California, woman fell to her death in 2006.[50]

Photograph gallery

El Caracol, observatory of Chichen Itza

Temple of the Warriors in 1986 - note that the Temple of the Big Tables, immediately to the left, was unrestored at that time

Stone Ring located 9 m (30 ft) above the floor of the Great Ballcourt

Platform of Venus in the Great Plaza

Kukulcán pyramid

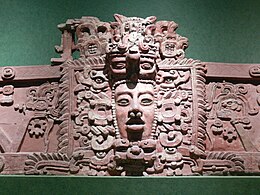

Mosaic mask on the western face of La Iglesia

Elaborate mosaic masks

A feathered serpent sculpture at the base of one of the stairways of Kukulcán (El Castillo)

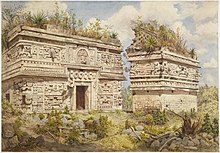

Las Monjas (Chichen Itza) in 1843 by Frederick Catherwood.[78]

Conservatory of Flowers

Golden Gate Park ConservatoryCalifornia Historical Landmark No. 841

Location San Francisco, California Coordinates  37°46′19.2″N122°27′36″W

37°46′19.2″N122°27′36″WBuilt 1878 Architect Lord & Burnham[1] Architectural style Italianate, Gothic[1] NRHP reference No. 71000184[1] CHISL No. 841 SFDL No. 50 Significant dates Added to NRHP October 14, 1971 Designated CHISL September 1, 1970[2] Designated SFDL December 4, 1972[3] (44 Years Ago) The Conservatory of Flowers is a greenhouse and botanical garden that houses a collection of rare and exotic plants in Golden Gate Park, San Francisco, California. With construction having been completed in 1879, it is the oldest building in the park. It was one of the first municipal conservatories constructed in the United States and is the oldest remaining municipal wooden conservatory in the country. For these distinctions and for its associated historical, architectural, and engineering merits, the Conservatory of Flowers is listed on the National Register of Historic Places and the California Register of Historical Places. It is a California Historical Landmark and a San Francisco Designated Landmark.

Architectural description[edit]

Front entrance of the conservatory in 2006 This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)The Conservatory of Flowers is an elaborate Victorian greenhouse with a central dome rising nearly 60 feet (18 m) high and arch-shaped wings extending from it for an overall length of 240 feet (73 m). The building sits atop a gentle slope overlooking Conservatory Valley. The structural members are articulated through one predominant form, a four-centered or Tudor arch.

The Conservatory of Flowers consists of a wood structural skeleton with glass walls set on a raised masonry foundation. The entire structure has a shallow E-shaped plan that is oriented along an east–west axis. The central 60-foot (18 m) high pavilion is entered through a one-story, glassed-in vestibule with a gable roof on the south side of the pavilion. Flanking the rotunda to the east and west are one-story, symmetrical wings framed by wood arches. Each wing is L-shaped in plan, with cupolas adorning the intersection of the two segments.

The octagonal pavilion supports an arched roof that is, in turn, surmounted by a clerestory and dome. The clerestory is supported by eight free-standing, wood-clad, cast-iron columns located within the rotunda and grouped in pairs. Projecting from the pavilion roof on the east, west, and south elevations are dormer windows with peak roofs. Between major arched structural framing members are wood muntins that hold the glass lights on their sides. The lights lap one over one another like shingles and follow the curve of the arches.

The Lowlands Gallery The construction of each arch is aesthetically appealing in its simplicity, but also structurally clever in that it takes maximum advantage of wood as a building material while overcoming its inherent structural shortcomings. From a structural perspective, the arch design utilizes the mechanical properties of the material. Wood is strongest along the length of the grain and weakest along the end grain. The use of short arch components with shallow radii minimized the amount of weaker-end grain exposed to structural forces. The assembly of the arch with several small pieces of wood, the shapes of which are identical from arch to arch, was efficient. It allowed the fabricator to set machines with guides and templates so that cutting the multiple-arch components was a simple task. Furthermore, the design required little material, since each individual arch component has only a shallow radius. Moreover, by using relatively narrow widths of lumber, the chance of warping was minimized. Finally, there was an efficiency realized in transportation, as the small size of the arch components allowed them to be easily stored and shipped.

The structural wood arches and their method of construction, along with the decorative woodwork and unique lapped glazing, define the character of the conservatory. The major character-defining elements consist of ornamental and structural woodwork, including the method of fabrication used for the arches, the lapped glazing system, the ventilation system, and the building's siting and exterior landscaping.[4]

Grounds and greenhouse Rooms within the conservatory[edit]

The Aquatic Plants room with flowing water, carnivorous plants, and some giant Victoria lilies - Potted Plants Gallery: The Potted Plant room holds various unusual plants. The pots and urns that hold the plants were created by various artists from around the world.[5] This room is maintained at hotter temperatures to accommodate the needs of the plants. The Potted Plant Gallery follows Victorian architecture and the 19th century idea of displaying tropical plants in non-tropical parts of the world.[5]

- Lowlands Gallery: The Lowlands Gallery contains plants from the tropics of South America (near the equator).[6] This room also contains plants that produce more well-known products such as bananas, coffee, and cinnamon.[6] The room is usually kept around 70 °F with a very high level of humidity through the use of a frequent system of misters, as the Lowland Tropics typically get 100–400 inches of rain each year and are located in elevations from 3,000 feet to sea level.[6]

- Highlands Gallery: The Highlands Gallery contains native plants from South to Central America.[7] Its plants collect moisture from the air, and from water that drips from the trees above. Due to its drastically higher elevation (3,000–10,000 feet), this room is kept cooler than the Lowlands Gallery (around 65 °F) and is kept at a very high level of humidity through the use of a misting system, as the Highland Tropics typically receive 200 inches of rain per year.[7]

- Aquatics Gallery: The Aquatic Plants room is similar in conditions as those near the Amazon River.[8] As such, many carnivorous plants that thrive in hot, humid environments grow throughout the room. The soil is mostly lacking in nutrients and the carnivorous plants are kept very moist by condensation of the water in the extremely humid air.[8] The room also contains two large ponds, one holding 9,000 gallons of water, and the other holding half as much.[8] Both ponds are kept at 83 °F and are maintained using beneficial bacteria, filters, water heaters, and solutions to prevent algae buildup.[8]

History and construction[edit]

Historical context[edit]

In both Europe and America, the 19th century brought increased urbanization and industrialization. In response, city governments began providing open spaces and natural settings for public use.[9] The profession of Landscape Architecture expanded during the later part of the 19th century, and park design became a large part of this new profession's repertoire. In addition, a significant outgrowth of the need for natural surroundings in urban contexts was an increase in the study of plant sciences during this period, both by professionals and amateurs. A building type called the glasshouse or conservatory took shape, in which the city-dweller could view masterpieces of the plant world otherwise unavailable in urban environments. Municipalities and individuals spent a great deal of time and money to construct these building types, which became known as "theaters of nature."

The 19th-century glasshouse grew out of the city-dweller's desire to bring nature and the natural into urban life.[10] These structures became popular in urban, public, and semi-public settings. As these structures gained popularity in Europe, greenhouses began to be constructed on larger scales and of stronger materials. One engineer, Joseph Paxton (1803–1865), had an enormous effect on the development of the conservatory building type. His structures called for a system of glass and metal roof construction, whereas past structures had typically been constructed of wood and glass. His choice of materials allowed designs for glasshouses of substantially larger scales. His best known example is the Crystal Palace at the world's first International Exhibition in 1851. Elsewhere in Europe, Hector Horeau designed several conservatories of glass and iron, such as the Lyons Conservatory in France of 1847. In Germany, August von Voit designed the Great Palm House in the Old Botanical Gardens in Munich in 1860. Another prominent example is the Palm House in the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew in London.

The engineering of the Crystal Palace allowed much larger greenhouses to be constructed.The Kew Gardens Palm House has been described as the inspiration for the Conservatory of Flowers.The increased use of glass and iron as building materials also impacted the development of the glasshouse. The decades following the construction of the Crystal Palace saw a decline in the use of wood structural members for the construction of large European greenhouses or conservatories. Many manufacturers had found that the humid heat necessary to successfully propagate numerous plant varieties often destroyed wood structural members in short periods of time.[11]

Following European fashions, wealthy Americans began to construct conservatories in the mid-19th century on private estates.

These structures were enjoyed by a broad cross-section of the public and were popular throughout California's early history. Structures of various shapes and sizes were built in Victorian California, ranging from an attached and glassed-in wing for a residence, to a great domed or compartmentalized, detached glasshouse.[12] Examples of wealthy Californians who built conservatories in their private estates include: A.K.P. (Albion Keith Paris) Harmon, for his Oakland Lake Merritt Estate (which later became Lakeside Park); Frederick Delger; Frank M. Smith; Darius Ogden Mills (Millbrae); and Luther Burbank, for his own experiments with plant germination (Santa Rosa). These examples all used wood as structural members.[13]

The conservatory[edit]

The material for two 12,000 square feet (1,100 m2) conservatories modeled after Kew Gardens in London was originally bought in 1876 by James Lick, an eccentric businessman, piano maker, and successful real estate investor who was a patron of the sciences. It is believed that Lick purchased the materials from Lord & Burnham, a manufacturer of greenhouses located in upstate New York, and these were sent in kit form, to be assembled on site. The order is said to have been the company's first big sale. The 33 tons of glass were sent by boat – most probably one chartered by Lick – from New York, around Cape Horn to San Francisco Bay.[14]

The conservatories were intended for the City of San Jose, where Lick had built a mansion surrounded by exotic plants imported from South America and around the world. Lick died in 1876 before constructing the conservatory on his estate, and it was put up for sale by his trustees. The material ended up in the possession of various beneficiaries of Lick's will, the California Academy of Sciences, and the Society of California Pioneers. In 1877, the Society sold it to "a group of 27 prominent San Franciscans and local philanthropists", which included Leland Stanford, Charles Crocker, Claus Spreckels and former mayor William Alvord, who offered it as a gift to the City of San Francisco for use in Golden Gate Park, which was then under construction. The Parks Commission accepted the gift and in 1878 hired Lord & Burnham to supervise the erection of the structure. It is believed that the glass for the second conservatory may have been used in other structures in the park.[14] Records indicate the construction costs were roughly $30,000.[15]

The specific architect of the greenhouse is not known for certain. The San Francisco Public Library holds a document entitled Information about Samuel Charles Bugbee, written by a relative, Arthur S. Bugbee, in 1957. It indicates that the architect Samual Charles Bugbee, whose works included the homes of Leland Stanford and Charles Crocker and the Mendocino Presbyterian Church, may also have designed the Conservatory of Flowers.

Once open in April 1879, the Conservatory contained a large variety of rare and tropical plants, including a giant water lily (Victoria regia), which at the time was the only known specimen in the United States.[16]

Wood vs. iron[edit]

The Conservatory of Flowers was constructed of wood rather than iron, as was common in the later part of the 19th century, because wood was plentiful in the west. Cast-iron greenhouses do not appear to have been widely manufactured in America until the 1880s. Materials analysis suggests that the structural wooden members of the Conservatory greenhouse were constructed of indigenous California Coast Redwood.[17]

Other known American wood conservatories of this period included Lyndhurst in Tarrytown, New York. The Lyndhurst Conservatory, constructed in 1869 of wood by the estate's first owner George Merritt, was destroyed by fire in 1880. The estate's second owner, Jay Gould, rebuilt the conservatory in 1881, hiring the local firm of Lord & Burnham – which had moved from upstate New York to Irvington, New York to be closer to its Hudson Valley clientele,[14] to manufacture his greenhouse. The 1881 Lord & Burnham structure was composed primarily of cast iron and glass. The Gould Conservatory at Lyndhurst is credited with being the first conservatory of iron in the United States and with inspiring subsequent structures of the same material. After their success with the Gould Conservatory of 1881, Lord & Burnham and other conservatory manufacturers apparently produced few large conservatories of wood.[18]

The Conservatory is now the oldest wood-and-glass conservatory in North America open to the public.[14]

Statistics[edit]

The conservatory has 16,800 window panes. The upper dome of the conservatory weighs 14.5 tonnes.

Langley's San Francisco Directory for the Year Commencing April 1879 discussed the construction of the Conservatory of Flowers:

The whole building required in its construction twenty-six thousand square feet of glass weighing twenty-five tons, and two tones of putty. It is a marvel of architectural beauty, surpassing in this respect any similar construction in the United States, and is only equaled in size by the Government Conservatory of in the Horticultural Gardens at Washington.[19]

Repair campaigns[edit]

The conservatory, as it appeared in 1879, before its dome was replaced following the 1883 fire Through its life, the Conservatory of Flowers has undergone several repair campaigns. The Palm Room, located in the center of the building, was seriously damaged in a fire in 1883. Its dome was completely reconstructed at this time. It sustained little damage following the 1906 earthquake. After a second fire damaged the structure in 1918, repairs were made as needed but were not thoroughly documented. No significant documented repairs to the building took place again until sometime after World War II, when certain portions of the wood work, including structural elements, were replaced. In 1959, wood windows at the base of the glazed walls at the building's perimeter were infilled with concrete panels that were cast to match the profiles of the original construction. In 1964–65, the clerestory of the Palm Room underwent reconstruction. The columns, lintels, and sills in this area were replaced by pressure-treated redwood. Five hundred lineal feet of the exterior cap molding, which covers the arches, was replaced at this time as well. Between 1978 and 1982, major repairs were performed on deteriorated woodwork. The areas that were repaired during this time did not overlap the 1960s' repairs to the clerestory.

In general, it appears that after 1914 most maintenance work was undertaken only when conditions presented a safety hazard, mechanical systems were in need of repair, or the building became extremely unsightly. Lack of scheduled maintenance affects the performance of building materials. Wood, in particular, requires proper maintenance of paint coatings to control the development of rot. In this building, it is important to maintain the condition of the interior, as well as exterior, coatings because of the humid indoor environment. Also necessary is the maintenance of waterproofing details, such as flashing, to prevent water from accumulating in concealed areas. It is therefore not surprising that rot developed in the building, and significant repairs to the wood elements of the building were necessary over time, given its somewhat irregular maintenance history.[20]

Early years[edit]

In the first years after the conservatory was constructed, ongoing maintenance was necessary for both the structure and its collection. This included repairing the boilers in the furnace room, the installation of ventilators, and the installation of a cement floor. At this point, the conservatory held over 9,000 plants of various kinds.[21]

1883 fire[edit]

The conservatory in 1897 In January 1883, the conservatory caught fire, with the main dome sustaining the heaviest damage. Evidence suggests the fire started as the result of intense heat generated by the furnace. Charles Crocker donated $10,000 toward the repair fund. The reconstructed dome included the addition of a clerestory. The original dome was saucer-shaped, while the replacement dome was more classically domical in its appearance, and was raised by 6 feet (1.8 m).[14] The other major change was the finial, which prior to the fire consisted of an eagle figure, whereas the replacement feature is a traditional turned finial of wood. This has been the only major change in the overall form of the building during its lifetime.

The remainder of the nineteenth century[edit]

Records indicate ongoing maintenance included painting in 1887-1889 and repainting again in 1890. In 1894, the conservatory's surrounding landscaping saw numerous transformations in preparations for the California Midwinter International Exposition of 1894. Another fire struck the building in 1895.[14]

The conservatory again was repainted in 1899 and received new floors of grooved concrete. At this point, the old floors, some of wood and some of concrete, were replaced by new grooved concrete. The grooves in the floor were intended to carry off the surplus water and make a visit to the conservatory more comfortable and pleasant. Several wooden plant benches that had rotted out were replaced by benches made of concrete wire netting to stand the constant change of temperature better than wood.

The conservatory, one month after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake The 1906 earthquake[edit]

The San Francisco earthquake and fire of 1906 did little damage to the Conservatory of Flowers. The structure is visible in a number of photographs of refugees living in Golden Gate Park after the disaster. However, records indicate that reconstruction costs ensued to the surrounding landscape from refugees living in the park.

Early twentieth-century repairs[edit]

Minor repairs were made to the Conservatory of Flowers in 1912 and 1913, including carpentry, cement setting for plant benches, and other small repairs. In 1918 a fire, commencing in the furnace room, caused damage to the conservatory's Potting Room and adjacent Dome Room. Repairs were made as needed. Another fire struck the Conservatory in 1918, causing the roof to partially collapse.[14]

Depression Era decline[edit]

During the Depression, the Conservatory of Flowers, due to apparent lack of maintenance, was in poor condition. The Park commissioners instructed the superintendent of Parks to close the Conservatory of Flowers in 1933 and construct proper barricades to prevent possible injury to citizens. The woodwork, foundations, girders, posts, and various structural members became rotted and decayed to such an extent that certain portions of the conservatory were reported to be in danger of falling and potentially causing great injury.

Orchids

Clerodendrum ugandense, blue butterfly bush Post-War era[edit]

This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (June 2020) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)In August 1946, the Conservatory of Flowers was painted and reglazed. A new electrical system, which allowed automatic control of the heating system for all of the conservatory, was installed in 1948. New piping was installed in 1949. A new water supply was installed in 1956.

In 1959, the original doors at the wing entrances were replaced with plate-glass windows and concrete panels. That same year, the lower ventilators at the building's perimeter were removed, and concrete panels, cast in the profile of the ventilators, were installed. This unfortunately seriously compromised the building's natural ventilation system. A few minor repairs were made in 1962 and 1965.

The Conservatory of Flowers was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 14, 1971. It had previously been named a California Historic Landmark on September 1, 1970, and would be designated a San Francisco Landmark on December 4, 1972.

A major rehabilitation project took place between 1978 and 1981. Work included the removal of all interior and exterior caps of the arches for visual inspection and probing, in order to detect pockets of wood rot. The portions of arches showing surface wood rot were treated with 'Git-Rot', a wood preservative. The caps that remained in good condition were salvaged and reinstalled.

Building evidence suggests that the exterior surfaces of the arches were originally fitted with copper flashing. The flashing was secured onto the arches and covered by the wood caps. In most locations that were inspected, the flashing had been removed, leaving only short remnants at random locations. The flashing was rolled up and taken away during the 1982 restoration effort. The flashing was an effective method of preventing moisture from entering the joints in the arch assembly, and its removal hastened deterioration. During this restoration as well, various deteriorated wood elements were replaced with pressure-treated, glue-laminated members.

Millennium rehabilitation[edit]

During the winter of 1995–1996, a series of large storms exacerbated the ongoing deterioration of the wood structure. The 100 mph (160 km/h) winds blew out 30,000 fogged white glass panes in the conservatory, shattered the white glass dome, and weakened the structure. In addition, 15 percent of the plant collection was lost due to exposure to the cold, wintry air and flying glass. After covering the holes with tarp and plywood and bringing in heaters, the conservatory contemplated farming out hundreds of plants to other institutions while the building was repaired. Some specimens however were too big or too old to move. The most challenging plant was the 112-year-old Brazilian philodendron that inhabited the shattered dome. A greenhouse was built to house the philodendron and other plants during renovation and afterwards used for expansion and keeping more exotic plants.

The conservatory was placed on the 1996 World Monuments Watch by the World Monuments Fund. The Fund aimed to encourage repair rather replacement of the original fabric, and provided funding from financial services company American Express.[22] Additional funding came from the Richard & Rhoda Goldman Fund.[14] In 1998, the National Trust for Historic Preservation adopted the conservatory into its Save America's Treasures program, launched as part of First Lady Hillary Clinton's Millennium Council projects. The publicity from these efforts eventually led to a fundraising campaign organized by what would become the San Francisco Parks Alliance to raise the money needed for rehabilitation, restoration, and stabilization of the conservatory.[14]

The construction lasted from 1999 until 2003. Initially estimated to cost $10 million, the actual final cost was $25 million. On September 20, 2003, the restored conservatory was once again opened to the public.

Repair methodology[edit]

Between November 1996 and January 1997, on-site surveys were conducted by a project team consisting of Tennebaum-Manheim Engineers and Architectural Resources Group. Surveyors included architects, materials conservators, architectural historians, structural engineers, mechanical engineers, and electrical engineers. The architectural and materials condition survey included a close-range visual inspection of all of the wood members in the building to determine locations of deteriorated wood, an analysis of the types of wood species occurring in the building, a study of the building's construction details, glazing, and a photographic survey. The structural survey included measuring the deflection of each of the arches and studying the probable lateral and vertical load paths to determine areas of weakness.[23]

Survey findings[edit]

The deterioration of wood occurred at typically vulnerable areas, such as the exposed end grain of arches and muntins and where wood members intersect. The humidity in the building was a contributing factor to wood deterioration. The level of moisture in the building was exacerbated by two conditions. First, the building's natural ventilation system had been removed in a past repair. The ventilators, which were originally located in the low wall area, had been filled in, and some ridge ventilators were inoperable. The air flow through the ventilators, which would have assisted in the evaporation of water, was not occurring. Second, the penetration of rain water from the exterior of the building, because of inadequate or deteriorated waterproofing, had increased the level of moisture in the wood. The copper sheathing that had originally capped the arch exteriors, in addition to acting as a moisture barrier, may have been acting as a biocide through copper oxides inhibiting wood rot.[13]

Repair process[edit]

Due to the level of deterioration and concerns relating to the building's long-term maintenance, a scheme was used to restore the wood structure. This involved disassembling the structure, repairing salvageable materials, and replacing materials deteriorated beyond repair with old-growth redwood that had fallen naturally or had been left behind by loggers. This was possible due to the original method used to fabricate the structure.

The construction sequence was as follows. First, temporary protection for those plants that could not be moved was provided. Then, the glass was carefully removed from the building, and historic glazing was salvaged. Structural wood elements of the building (arches), as well as muntins that held the glazing, were disassembled. The location of each element was recorded for reinstallation. The lead-based coatings were stripped from the wood members. Each wooden piece was then tested for its strength and determined if repair or replacement was appropriate.

Contemporary status[edit]

In January 2022, legislation was proposed by Mayor London Breed that would put the Conservatory under the oversight of the San Francisco Botanical Garden Society, along with the Japanese Tea Garden and the Botanical Garden itself, under the name "The Gardens of Golden Gate Park". Under the proposal, admission to the gardens would be free.[14]

![Las Monjas (Chichen Itza) in 1843 by Frederick Catherwood.[78]](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/a/ae/Brooklyn_Museum_-_Las_Monjas_Chichen_Itza_Yucatan_-_Frederick_Catherwood.jpg/372px-Brooklyn_Museum_-_Las_Monjas_Chichen_Itza_Yucatan_-_Frederick_Catherwood.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment