This morning on the day of May 27, 2022 in explanation is for the people reading the King James Version only as most would not be interested in the arithmetic of such a book.

The word in the King James Version “alien” is in the book of Job found in chapter 19, verse 15 and is quoted at: “Those who dwell in my house, and my maidservants, Count me as a stranger: I am an alien in their sight.”

The word in the chapter of the book of Job found in the King James Version of the Bible is 3.141 and is in verse of what is known worldwide as reincarnation.

Reincarnation is a direct correlation at 3.141, pi and in directive of any handwritten mathematical demonstration of the constant that represents such at the direction of 3.141 and will increase Cantore Arithmetic as geometry for the science of Cantore Physics.

Born again may be incarnation.

Geometry

Geometry (from Ancient Greek γεωμετρία (geōmetría) 'land measurement'; from γῆ (gê) 'earth, land', and μέτρον (métron) 'a measure') is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space that are related with distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures.[1] A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is called a geometer.

Until the 19th century, geometry was almost exclusively devoted to Euclidean geometry,[a] which includes the notions of point, line, plane, distance, angle, surface, and curve, as fundamental concepts.[2]

During the 19th century several discoveries enlarged dramatically the scope of geometry. One of the oldest such discoveries is Gauss' Theorema Egregium ("remarkable theorem") that asserts roughly that the Gaussian curvature of a surface is independent from any specific embedding in a Euclidean space. This implies that surfaces can be studied intrinsically, that is, as stand-alone spaces, and has been expanded into the theory of manifolds and Riemannian geometry.

Later in the 19th century, it appeared that geometries without the parallel postulate (non-Euclidean geometries) can be developed without introducing any contradiction. The geometry that underlies general relativity is a famous application of non-Euclidean geometry.

Since then, the scope of geometry has been greatly expanded, and the field has been split in many subfields that depend on the underlying methods—differential geometry, algebraic geometry, computational geometry, algebraic topology, discrete geometry(also known as combinatorial geometry), etc.—or on the properties of Euclidean spaces that are disregarded—projective geometrythat consider only alignment of points but not distance and parallelism, affine geometry that omits the concept of angle and distance, finite geometry that omits continuity, and others.

Originally developed to model the physical world, geometry has applications in almost all sciences, and also in art, architecture, and other activities that are related to graphics.[3] Geometry also has applications in areas of mathematics that are apparently unrelated. For example, methods of algebraic geometry are fundamental in Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem, a problem that was stated in terms of elementary arithmetic, and remained unsolved for several centuries.

History

The earliest recorded beginnings of geometry can be traced to ancient Mesopotamia and Egypt in the 2nd millennium BC.[4][5] Early geometry was a collection of empirically discovered principles concerning lengths, angles, areas, and volumes, which were developed to meet some practical need in surveying, construction, astronomy, and various crafts. The earliest known texts on geometry are the Egyptian Rhind Papyrus (2000–1800 BC) and Moscow Papyrus (c. 1890 BC), and the Babylonian clay tablets, such as Plimpton 322(1900 BC). For example, the Moscow Papyrus gives a formula for calculating the volume of a truncated pyramid, or frustum.[6] Later clay tablets (350–50 BC) demonstrate that Babylonian astronomers implemented trapezoid procedures for computing Jupiter's position and motion within time-velocity space. These geometric procedures anticipated the Oxford Calculators, including the mean speed theorem, by 14 centuries.[7] South of Egypt the ancient Nubians established a system of geometry including early versions of sun clocks.[8][9]

In the 7th century BC, the Greek mathematician Thales of Miletus used geometry to solve problems such as calculating the height of pyramids and the distance of ships from the shore. He is credited with the first use of deductive reasoning applied to geometry, by deriving four corollaries to Thales' theorem.[10] Pythagoras established the Pythagorean School, which is credited with the first proof of the Pythagorean theorem,[11] though the statement of the theorem has a long history.[12][13] Eudoxus (408–c. 355 BC) developed the method of exhaustion, which allowed the calculation of areas and volumes of curvilinear figures,[14] as well as a theory of ratios that avoided the problem of incommensurable magnitudes, which enabled subsequent geometers to make significant advances. Around 300 BC, geometry was revolutionized by Euclid, whose Elements, widely considered the most successful and influential textbook of all time,[15] introduced mathematical rigor through the axiomatic method and is the earliest example of the format still used in mathematics today, that of definition, axiom, theorem, and proof. Although most of the contents of the Elements were already known, Euclid arranged them into a single, coherent logical framework.[16] The Elements was known to all educated people in the West until the middle of the 20th century and its contents are still taught in geometry classes today.[17] Archimedes (c. 287–212 BC) of Syracuse used the method of exhaustion to calculate the area under the arc of a parabolawith the summation of an infinite series, and gave remarkably accurate approximations of pi.[18] He also studied the spiral bearing his name and obtained formulas for the volumes of surfaces of revolution.

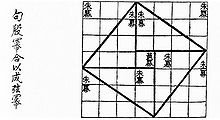

Indian mathematicians also made many important contributions in geometry. The Satapatha Brahmana (3rd century BC) contains rules for ritual geometric constructions that are similar to the Sulba Sutras.[19] According to (Hayashi 2005, p. 363), the Śulba Sūtras contain "the earliest extant verbal expression of the Pythagorean Theorem in the world, although it had already been known to the Old Babylonians. They contain lists of Pythagorean triples,[20] which are particular cases of Diophantine equations.[21] In the Bakhshali manuscript, there is a handful of geometric problems (including problems about volumes of irregular solids). The Bakhshali manuscript also "employs a decimal place value system with a dot for zero."[22] Aryabhata's Aryabhatiya (499) includes the computation of areas and volumes. Brahmagupta wrote his astronomical work Brāhma Sphuṭa Siddhānta in 628. Chapter 12, containing 66 Sanskrit verses, was divided into two sections: "basic operations" (including cube roots, fractions, ratio and proportion, and barter) and "practical mathematics" (including mixture, mathematical series, plane figures, stacking bricks, sawing of timber, and piling of grain).[23] In the latter section, he stated his famous theorem on the diagonals of a cyclic quadrilateral. Chapter 12 also included a formula for the area of a cyclic quadrilateral (a generalization of Heron's formula), as well as a complete description of rational triangles (i.e. triangles with rational sides and rational areas).[23]

In the Middle Ages, mathematics in medieval Islam contributed to the development of geometry, especially algebraic geometry.[24][25] Al-Mahani (b. 853) conceived the idea of reducing geometrical problems such as duplicating the cube to problems in algebra.[26] Thābit ibn Qurra (known as Thebit in Latin) (836–901) dealt with arithmetic operations applied to ratios of geometrical quantities, and contributed to the development of analytic geometry.[27] Omar Khayyám (1048–1131) found geometric solutions to cubic equations.[28] The theorems of Ibn al-Haytham (Alhazen), Omar Khayyam and Nasir al-Din al-Tusi on quadrilaterals, including the Lambert quadrilateral and Saccheri quadrilateral, were early results in hyperbolic geometry, and along with their alternative postulates, such as Playfair's axiom, these works had a considerable influence on the development of non-Euclidean geometry among later European geometers, including Witelo (c. 1230–c. 1314), Gersonides (1288–1344), Alfonso, John Wallis, and Giovanni Girolamo Saccheri.[dubious ][29]

In the early 17th century, there were two important developments in geometry. The first was the creation of analytic geometry, or geometry with coordinates and equations, by René Descartes (1596–1650) and Pierre de Fermat (1601–1665).[30] This was a necessary precursor to the development of calculus and a precise quantitative science of physics.[31] The second geometric development of this period was the systematic study of projective geometry by Girard Desargues (1591–1661).[32] Projective geometry studies properties of shapes which are unchanged under projections and sections, especially as they relate to artistic perspective.[33]

Two developments in geometry in the 19th century changed the way it had been studied previously.[34] These were the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky, János Bolyai and Carl Friedrich Gauss and of the formulation of symmetry as the central consideration in the Erlangen Programme of Felix Klein (which generalized the Euclidean and non-Euclidean geometries). Two of the master geometers of the time were Bernhard Riemann (1826–1866), working primarily with tools from mathematical analysis, and introducing the Riemann surface, and Henri Poincaré, the founder of algebraic topology and the geometric theory of dynamical systems. As a consequence of these major changes in the conception of geometry, the concept of "space" became something rich and varied, and the natural background for theories as different as complex analysis and classical mechanics.[35]

Main concepts

The following are some of the most important concepts in geometry.[2][36][37]

Axioms

Euclid took an abstract approach to geometry in his Elements,[38] one of the most influential books ever written.[39] Euclid introduced certain axioms, or postulates, expressing primary or self-evident properties of points, lines, and planes.[40] He proceeded to rigorously deduce other properties by mathematical reasoning. The characteristic feature of Euclid's approach to geometry was its rigor, and it has come to be known as axiomatic or synthetic geometry.[41] At the start of the 19th century, the discovery of non-Euclidean geometries by Nikolai Ivanovich Lobachevsky (1792–1856), János Bolyai (1802–1860), Carl Friedrich Gauss (1777–1855) and others[42] led to a revival of interest in this discipline, and in the 20th century, David Hilbert (1862–1943) employed axiomatic reasoning in an attempt to provide a modern foundation of geometry.[43]

Objects

Points

Points are generally considered fundamental objects for building geometry. They may be defined by the properties that thay must have, as in Euclid's definition as "that which has no part",[44] or in synthetic geometry. In modern mathematics, they are generally defined as elements of a set called space, which is itself axiomatically defined.

With these modern definitions, every geometric shape is defined as a set of points; this is not the case in synthetic geometry, where a line is another fundamental object that is not viewed as the set of the points through which it passes.

However, there has modern geometries, in which points are not primitive objects, or even without points.[45][46] One of the oldest such geometries is Whitehead's point-free geometry, formulated by Alfred North Whitehead in 1919–1920.

Lines

Euclid described a line as "breadthless length" which "lies equally with respect to the points on itself".[44] In modern mathematics, given the multitude of geometries, the concept of a line is closely tied to the way the geometry is described. For instance, in analytic geometry, a line in the plane is often defined as the set of points whose coordinates satisfy a given linear equation,[47] but in a more abstract setting, such as incidence geometry, a line may be an independent object, distinct from the set of points which lie on it.[48] In differential geometry, a geodesic is a generalization of the notion of a line to curved spaces.[49]

Planes

In Euclidean geometry a plane is a flat, two-dimensional surface that extends infinitely;[44] the definitions for other types of geometries are generalizations of that. Planes are used in many areas of geometry. For instance, planes can be studied as a topological surface without reference to distances or angles;[50] it can be studied as an affine space, where collinearity and ratios can be studied but not distances;[51] it can be studied as the complex plane using techniques of complex analysis;[52] and so on.

Angles

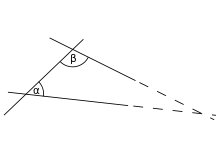

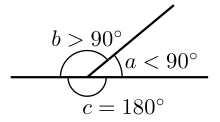

Euclid defines a plane angle as the inclination to each other, in a plane, of two lines which meet each other, and do not lie straight with respect to each other.[44] In modern terms, an angle is the figure formed by two rays, called the sides of the angle, sharing a common endpoint, called the vertex of the angle.[53]

In Euclidean geometry, angles are used to study polygons and triangles, as well as forming an object of study in their own right.[44] The study of the angles of a triangle or of angles in a unit circle forms the basis of trigonometry.[54]

In differential geometry and calculus, the angles between plane curves or space curves or surfaces can be calculated using the derivative.[55][56]

Curves

A curve is a 1-dimensional object that may be straight (like a line) or not; curves in 2-dimensional space are called plane curves and those in 3-dimensional space are called space curves.[57]

In topology, a curve is defined by a function from an interval of the real numbers to another space.[50] In differential geometry, the same definition is used, but the defining function is required to be differentiable [58] Algebraic geometry studies algebraic curves, which are defined as algebraic varieties of dimensionone.[59]

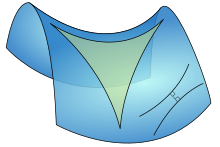

Surfaces

A surface is a two-dimensional object, such as a sphere or paraboloid.[60] In differential geometry[58] and topology,[50] surfaces are described by two-dimensional 'patches' (or neighborhoods) that are assembled by diffeomorphisms or homeomorphisms, respectively. In algebraic geometry, surfaces are described by polynomial equations.[59]

Manifolds

A manifold is a generalization of the concepts of curve and surface. In topology, a manifold is a topological space where every point has a neighborhood that is homeomorphic to Euclidean space.[50] In differential geometry, a differentiable manifold is a space where each neighborhood is diffeomorphic to Euclidean space.[58]

Manifolds are used extensively in physics, including in general relativity and string theory.[61]

Length, area, and volume

Length, area, and volume describe the size or extent of an object in one dimension, two dimension, and three dimensions respectively.[62]

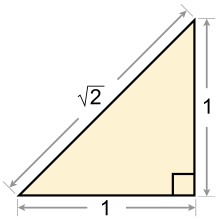

In Euclidean geometry and analytic geometry, the length of a line segment can often be calculated by the Pythagorean theorem.[63]

Area and volume can be defined as fundamental quantities separate from length, or they can be described and calculated in terms of lengths in a plane or 3-dimensional space.[62] Mathematicians have found many explicit formulas for area and formulas for volume of various geometric objects. In calculus, area and volume can be defined in terms of integrals, such as the Riemann integral[64] or the Lebesgue integral.[65]

Metrics and measures

The concept of length or distance can be generalized, leading to the idea of metrics.[66] For instance, the Euclidean metric measures the distance between points in the Euclidean plane, while the hyperbolic metric measures the distance in the hyperbolic plane. Other important examples of metrics include the Lorentz metric of special relativity and the semi-Riemannian metrics of general relativity.[67]

In a different direction, the concepts of length, area and volume are extended by measure theory, which studies methods of assigning a size or measure to sets, where the measures follow rules similar to those of classical area and volume.[68]

Congruence and similarity

Congruence and similarity are concepts that describe when two shapes have similar characteristics.[69] In Euclidean geometry, similarity is used to describe objects that have the same shape, while congruence is used to describe objects that are the same in both size and shape.[70] Hilbert, in his work on creating a more rigorous foundation for geometry, treated congruence as an undefined term whose properties are defined by axioms.

Congruence and similarity are generalized in transformation geometry, which studies the properties of geometric objects that are preserved by different kinds of transformations.[71]

Compass and straightedge constructions

Classical geometers paid special attention to constructing geometric objects that had been described in some other way. Classically, the only instruments used in most geometric constructions are the compass and straightedge.[b] Also, every construction had to be complete in a finite number of steps. However, some problems turned out to be difficult or impossible to solve by these means alone, and ingenious constructions using neusis, parabolas and other curves, or mechanical devices, were found.

Dimension

Where the traditional geometry allowed dimensions 1 (a line), 2 (a plane) and 3 (our ambient world conceived of as three-dimensional space), mathematicians and physicists have used higher dimensions for nearly two centuries.[72] One example of a mathematical use for higher dimensions is the configuration space of a physical system, which has a dimension equal to the system's degrees of freedom. For instance, the configuration of a screw can be described by five coordinates.[73]

In general topology, the concept of dimension has been extended from natural numbers, to infinite dimension (Hilbert spaces, for example) and positive real numbers (in fractal geometry).[74] In algebraic geometry, the dimension of an algebraic variety has received a number of apparently different definitions, which are all equivalent in the most common cases.[75]

Symmetry

The theme of symmetry in geometry is nearly as old as the science of geometry itself.[76] Symmetric shapes such as the circle, regular polygons and platonic solids held deep significance for many ancient philosophers[77] and were investigated in detail before the time of Euclid.[40] Symmetric patterns occur in nature and were artistically rendered in a multitude of forms, including the graphics of Leonardo da Vinci, M. C. Escher, and others.[78] In the second half of the 19th century, the relationship between symmetry and geometry came under intense scrutiny. Felix Klein's Erlangen program proclaimed that, in a very precise sense, symmetry, expressed via the notion of a transformation group, determines what geometry is.[79] Symmetry in classical Euclidean geometry is represented by congruences and rigid motions, whereas in projective geometry an analogous role is played by collineations, geometric transformations that take straight lines into straight lines.[80] However it was in the new geometries of Bolyai and Lobachevsky, Riemann, Clifford and Klein, and Sophus Lie that Klein's idea to 'define a geometry via its symmetry group' found its inspiration.[81] Both discrete and continuous symmetries play prominent roles in geometry, the former in topology and geometric group theory,[82][83] the latter in Lie theory and Riemannian geometry.[84][85]

A different type of symmetry is the principle of duality in projective geometry, among other fields. This meta-phenomenon can roughly be described as follows: in any theorem, exchange point with plane, join with meet, lies in with contains, and the result is an equally true theorem.[86] A similar and closely related form of duality exists between a vector space and its dual space.[87]

Contemporary geometry

Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry is geometry in its classical sense.[88] As it models the space of the physical world, it is used in many scientific areas, such as mechanics, astronomy, crystallography,[89] and many technical fields, such as engineering,[90] architecture,[91] geodesy,[92] aerodynamics,[93] and navigation.[94] The mandatory educational curriculum of the majority of nations includes the study of Euclidean concepts such as points, lines, planes, angles, triangles, congruence, similarity, solid figures, circles, and analytic geometry.[36]

Differential geometry

Differential geometry uses techniques of calculus and linear algebra to study problems in geometry.[95] It has applications in physics,[96]econometrics,[97] and bioinformatics,[98] among others.

In particular, differential geometry is of importance to mathematical physics due to Albert Einstein's general relativity postulation that the universe is curved.[99] Differential geometry can either be intrinsic (meaning that the spaces it considers are smooth manifolds whose geometric structure is governed by a Riemannian metric, which determines how distances are measured near each point) or extrinsic(where the object under study is a part of some ambient flat Euclidean space).[100]

Non-Euclidean geometry

Euclidean geometry was not the only historical form of geometry studied. Spherical geometry has long been used by astronomers, astrologers, and navigators.[101]

Immanuel Kant argued that there is only one, absolute, geometry, which is known to be true a priori by an inner faculty of mind: Euclidean geometry was synthetic a priori.[102]This view was at first somewhat challenged by thinkers such as Saccheri, then finally overturned by the revolutionary discovery of non-Euclidean geometry in the works of Bolyai, Lobachevsky, and Gauss (who never published his theory).[103] They demonstrated that ordinary Euclidean space is only one possibility for development of geometry. A broad vision of the subject of geometry was then expressed by Riemann in his 1867 inauguration lecture Über die Hypothesen, welche der Geometrie zu Grunde liegen (On the hypotheses on which geometry is based),[104] published only after his death. Riemann's new idea of space proved crucial in Albert Einstein's general relativity theory. Riemannian geometry, which considers very general spaces in which the notion of length is defined, is a mainstay of modern geometry.[81]

Topology

Topology is the field concerned with the properties of continuous mappings,[105] and can be considered a generalization of Euclidean geometry.[106] In practice, topology often means dealing with large-scale properties of spaces, such as connectedness and compactness.[50]

The field of topology, which saw massive development in the 20th century, is in a technical sense a type of transformation geometry, in which transformations are homeomorphisms.[107] This has often been expressed in the form of the saying 'topology is rubber-sheet geometry'. Subfields of topology include geometric topology, differential topology, algebraic topology and general topology.[108]

Algebraic geometry

The field of algebraic geometry developed from the Cartesian geometry of co-ordinates.[109] It underwent periodic periods of growth, accompanied by the creation and study of projective geometry, birational geometry, algebraic varieties, and commutative algebra, among other topics.[110] From the late 1950s through the mid-1970s it had undergone major foundational development, largely due to work of Jean-Pierre Serre and Alexander Grothendieck.[110] This led to the introduction of schemes and greater emphasis on topologicalmethods, including various cohomology theories. One of seven Millennium Prize problems, the Hodge conjecture, is a question in algebraic geometry.[111] Wiles' proof of Fermat's Last Theorem uses advanced methods of algebraic geometry for solving a long-standing problem of number theory.

In general, algebraic geometry studies geometry through the use of concepts in commutative algebra such as multivariate polynomials.[112] It has applications in many areas, including cryptography[113] and string theory.[114]

Complex geometry

Complex geometry studies the nature of geometric structures modelled on, or arising out of, the complex plane.[115][116][117] Complex geometry lies at the intersection of differential geometry, algebraic geometry, and analysis of several complex variables, and has found applications to string theory and mirror symmetry.[118]

Complex geometry first appeared as a distinct area of study in the work of Bernhard Riemann in his study of Riemann surfaces.[119][120][121] Work in the spirit of Riemann was carried out by the Italian school of algebraic geometry in the early 1900s. Contemporary treatment of complex geometry began with the work of Jean-Pierre Serre, who introduced the concept of sheaves to the subject, and illuminated the relations between complex geometry and algebraic geometry.[122][123] The primary objects of study in complex geometry are complex manifolds, complex algebraic varieties, and complex analytic varieties, and holomorphic vector bundles and coherent sheaves over these spaces. Special examples of spaces studied in complex geometry include Riemann surfaces, and Calabi–Yau manifolds, and these spaces find uses in string theory. In particular, worldsheets of strings are modelled by Riemann surfaces, and superstring theory predicts that the extra 6 dimensions of 10 dimensional spacetime may be modelled by Calabi–Yau manifolds.

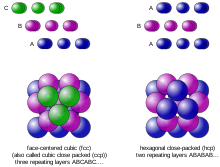

Discrete geometry

Discrete geometry is a subject that has close connections with convex geometry.[124][125][126] It is concerned mainly with questions of relative position of simple geometric objects, such as points, lines and circles. Examples include the study of sphere packings, triangulations, the Kneser-Poulsen conjecture, etc.[127][128] It shares many methods and principles with combinatorics.

Computational geometry

Computational geometry deals with algorithms and their implementations for manipulating geometrical objects. Important problems historically have included the travelling salesman problem, minimum spanning trees, hidden-line removal, and linear programming.[129]

Although being a young area of geometry, it has many applications in computer vision, image processing, computer-aided design, medical imaging, etc.[130]

Geometric group theory

Geometric group theory uses large-scale geometric techniques to study finitely generated groups.[131] It is closely connected to low-dimensional topology, such as in Grigori Perelman's proof of the Geometrization conjecture, which included the proof of the Poincaré conjecture, a Millennium Prize Problem.[132]

Geometric group theory often revolves around the Cayley graph, which is a geometric representation of a group. Other important topics include quasi-isometries, Gromov-hyperbolic groups, and right angled Artin groups.[131][133]

Convex geometry

Convex geometry investigates convex shapes in the Euclidean space and its more abstract analogues, often using techniques of real analysis and discrete mathematics.[134] It has close connections to convex analysis, optimization and functional analysis and important applications in number theory.

Convex geometry dates back to antiquity.[134] Archimedes gave the first known precise definition of convexity. The isoperimetric problem, a recurring concept in convex geometry, was studied by the Greeks as well, including Zenodorus. Archimedes, Plato, Euclid, and later Kepler and Coxeter all studied convex polytopes and their properties. From the 19th century on, mathematicians have studied other areas of convex mathematics, including higher-dimensional polytopes, volume and surface area of convex bodies, Gaussian curvature, algorithms, tilings and lattices.

Applications

Geometry has found applications in many fields, some of which are described below.

Art

Mathematics and art are related in a variety of ways. For instance, the theory of perspective showed that there is more to geometry than just the metric properties of figures: perspective is the origin of projective geometry.[135]

Artists have long used concepts of proportion in design. Vitruvius developed a complicated theory of ideal proportions for the human figure.[136] These concepts have been used and adapted by artists from Michelangelo to modern comic book artists.[137]

The golden ratio is a particular proportion that has had a controversial role in art. Often claimed to be the most aesthetically pleasing ratio of lengths, it is frequently stated to be incorporated into famous works of art, though the most reliable and unambiguous examples were made deliberately by artists aware of this legend.[138]

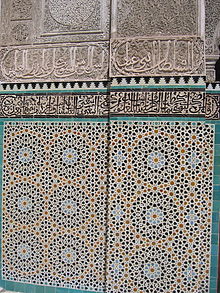

Tilings, or tessellations, have been used in art throughout history. Islamic art makes frequent use of tessellations, as did the art of M. C. Escher.[139] Escher's work also made use of hyperbolic geometry.

Cézanne advanced the theory that all images can be built up from the sphere, the cone, and the cylinder. This is still used in art theory today, although the exact list of shapes varies from author to author.[140][141]

Architecture

Geometry has many applications in architecture. In fact, it has been said that geometry lies at the core of architectural design.[142][143]Applications of geometry to architecture include the use of projective geometry to create forced perspective,[144] the use of conic sectionsin constructing domes and similar objects,[91] the use of tessellations,[91] and the use of symmetry.[91]

Physics

The field of astronomy, especially as it relates to mapping the positions of stars and planets on the celestial sphere and describing the relationship between movements of celestial bodies, have served as an important source of geometric problems throughout history.[145]

Riemannian geometry and pseudo-Riemannian geometry are used in general relativity.[146] String theory makes use of several variants of geometry,[147] as does quantum information theory.[148]

Other fields of mathematics

Calculus was strongly influenced by geometry.[30] For instance, the introduction of coordinates by René Descartes and the concurrent developments of algebra marked a new stage for geometry, since geometric figures such as plane curves could now be represented analytically in the form of functions and equations. This played a key role in the emergence of infinitesimal calculus in the 17th century. Analytic geometry continues to be a mainstay of pre-calculus and calculus curriculum.[149][150]

Another important area of application is number theory.[151] In ancient Greece the Pythagoreans considered the role of numbers in geometry. However, the discovery of incommensurable lengths contradicted their philosophical views.[152] Since the 19th century, geometry has been used for solving problems in number theory, for example through the geometry of numbers or, more recently, scheme theory, which is used in Wiles's proof of Fermat's Last Theorem.[153]

See also

Lists

- List of geometers

- List of formulas in elementary geometry

- List of geometry topics

- List of important publications in geometry

- Lists of mathematics topics

Related topics

- Descriptive geometry

- Finite geometry

- Flatland, a book written by Edwin Abbott Abbott about two- and three-dimensional space, to understand the concept of four dimensions

- List of interactive geometry software

Other fields

King James Version

The King James Version (KJV), also the King James Bible (KJB)[1] and the Authorized Version, is an English translation of the Christian Bible for the Church of England, which was commissioned in 1604 and published in 1611, by sponsorship of King James VI and I.[a][b] The books of the King James Version include 39 books of the Old Testament, an intertestamental section containing 14 books of what Protestants consider the Apocrypha, and the 27 books of the New Testament. Noted for its "majesty of style", the King James Version has been described as one of the most important books in English culture and a driving force in the shaping of the English-speaking world.[3][4]

The KJV was first printed by John Norton and Robert Barker, who both held the post of the King's Printer, and was the third translation into English language approved by the English Church authorities: The first had been the Great Bible, commissioned in the reign of King Henry VIII (1535), and the second had been the Bishops' Bible, commissioned in the reign of Queen Elizabeth I(1568).[5] In Geneva, Switzerland, the first generation of Protestant Reformers had produced the Geneva Bible of 1560[6] from the original Hebrew and Greek scriptures, which was influential in the writing of the Authorized King James Version.

In January 1604, King James convened the Hampton Court Conference, where a new English version was conceived in response to the problems of the earlier translations perceived by the Puritans,[7] a faction of the Church of England.[8]

James gave the translators instructions intended to ensure that the new version would conform to the ecclesiology, and reflect the episcopal structure, of the Church of England and its belief in an ordained clergy.[9] The translation was done by 6 panels of translators (47 men in all, most of whom were leading biblical scholars in England) who had the work divided up between them: the Old Testament was entrusted to three panels, the New Testament to two, and the Apocrypha to one.[10] In common with most other translations of the period, the New Testament was translated from Greek, the Old Testament from Hebrew and Aramaic, and the Apocrypha from Greek and Latin. In the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, the text of the Authorized Version replaced the text of the Great Bible for Epistle and Gospel readings (but not for the Psalter, which substantially retained Coverdale's Great Bible version), and as such was authorized by Act of Parliament.[11]

By the first half of the 18th century, the Authorized Version had become effectively unchallenged as the English translation used in Anglican and other English Protestant churches, except for the Psalms and some short passages in the Book of Common Prayer of the Church of England. Over the course of the 18th century, the Authorized Version supplanted the Latin Vulgate as the standard version of scripture for English-speaking scholars. With the development of stereotype printing at the beginning of the 19th century, this version of the Bible became the most widely printed book in history, almost all such printings presenting the standard text of 1769 extensively re-edited by Benjamin Blayney at Oxford, and nearly always omitting the books of the Apocrypha. Today the unqualified title "King James Version" usually indicates this Oxford standard text.

Name[edit]

The title of the first edition of the translation, in Early Modern English, was "THE HOLY BIBLE, Conteyning the Old Teſtament, AND THE NEW: Newly Tranſlated out of the Originall tongues: & with the former Tranſlations diligently compared and reuiſed, by his Maiesties ſpeciall Cõmandement". The title page carries the words "Appointed to be read in Churches",[12] and F. F. Bruce suggests it was "probably authorised by order in council" but no record of the authorization survives "because the Privy Council registers from 1600 to 1613 were destroyed by fire in January 1618/19".[13]

For many years it was common not to give the translation any specific name. In his Leviathan of 1651, Thomas Hobbes referred to it as "the English Translation made in the beginning of the Reign of King James".[14] A 1761 "Brief Account of the various Translations of the Bible into English" refers to the 1611 version merely as "a new, compleat, and more accurate Translation", despite referring to the Great Bible by its name, and despite using the name "Rhemish Testament" for the Douay–Rheims Bible version.[15] Similarly, a "History of England", whose fifth edition was published in 1775, writes merely that "[a] new translation of the Bible, viz., that now in Use, was begun in 1607, and published in 1611".[16]

King James's Bible is used as the name for the 1611 translation (on a par with the Genevan Bible or the Rhemish Testament) in Charles Butler's Horae Biblicae (first published 1797).[17] Other works from the early 19th century confirm the widespread use of this name on both sides of the Atlantic: it is found both in a "Historical sketch of the English translations of the Bible" published in Massachusetts in 1815,[18] and in an English publication from 1818, which explicitly states that the 1611 version is "generally known by the name of King James's Bible".[19] This name was also found as King James' Bible (without the final "s"): for example in a book review from 1811.[20] The phrase "King James's Bible" is used as far back as 1715, although in this case it is not clear whether this is a name or merely a description.[21]

The use of Authorized Version, capitalized and used as a name, is found as early as 1814.[22] For some time before this, descriptive phrases such as "our present, and only publicly authorised version" (1783),[23] "our Authorized version" (1731,[24] 1792[25]) and "the authorized version" (1801, uncapitalized)[26] are found. A more common appellation in the 17th and 18th centuries was "our English translation" or "our English version", as can be seen by searching one or other of the major online archives of printed books. In Britain, the 1611 translation is generally known as the "Authorized Version" today. The term is somewhat of a misnomer because the text itself was never formally "authorized", nor were English parish churches ever ordered to procure copies of it.[27]

King James' Version, evidently a descriptive phrase, is found being used as early as 1814.[28] "The King James Version" is found, unequivocally used as a name, in a letter from 1855.[29] The next year King James Bible, with no possessive, appears as a name in a Scottish source.[30] In the United States, the "1611 translation" (actually editions following the standard text of 1769, see below) is generally known as the King James Version today.

History[edit]

Earlier English translations[edit]

The followers of John Wycliffe undertook the first complete English translations of the Christian scriptures in the 14th century. These translations were banned in 1409 due to their association with the Lollards.[31] The Wycliffe Bible pre-dated the printing press but it was circulated very widely in manuscript form, often inscribed with a date which was earlier than 1409 in order to avoid the legal ban. Because the text of the various versions of the Wycliffe Bible was translated from the Latin Vulgate, and because it also contained no heterodox readings, the ecclesiastical authorities had no practical way to distinguish the banned version; consequently, many Catholic commentators of the 15th and 16th centuries (such as Thomas More) took these manuscripts of English Bibles and claimed that they represented an anonymous earlier orthodox translation.

In 1525, William Tyndale, an English contemporary of Martin Luther, undertook a translation of the New Testament.[32] Tyndale's translation was the first printed Bible in English. Over the next ten years, Tyndale revised his New Testament in the light of rapidly advancing biblical scholarship, and embarked on a translation of the Old Testament.[33] Despite some controversial translation choices, and in spite of Tyndale's execution on charges of heresy for having made the translated Bible, the merits of Tyndale's work and prose style made his translation the ultimate basis for all subsequent renditions into Early Modern English.[34] With these translations lightly edited and adapted by Myles Coverdale, in 1539, Tyndale's New Testament and his incomplete work on the Old Testament became the basis for the Great Bible. This was the first "authorised version" issued by the Church of England during the reign of King Henry VIII.[5]When Mary I succeeded to the throne in 1553, she returned the Church of England to the communion of the Catholic faith and many English religious reformers fled the country,[35] some establishing an English-speaking colony at Geneva. Under the leadership of John Calvin, Geneva became the chief international centre of Reformed Protestantism and Latin biblical scholarship.[36]

These English expatriates undertook a translation that became known as the Geneva Bible.[37] This translation, dated to 1560, was a revision of Tyndale's Bible and the Great Bible on the basis of the original languages.[38] Soon after Elizabeth I took the throne in 1558, the flaws of both the Great Bible and the Geneva Bible (namely, that the Geneva Bible did not "conform to the ecclesiology and reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England and its beliefs about an ordained clergy") became painfully apparent.[39] In 1568, the Church of England responded with the Bishops' Bible, a revision of the Great Bible in the light of the Geneva version.[40] While officially approved, this new version failed to displace the Geneva translation as the most popular English Bible of the age—in part because the full Bible was only printed in lectern editions of prodigious size and at a cost of several pounds.[41] Accordingly, Elizabethan lay people overwhelmingly read the Bible in the Geneva Version—small editions were available at a relatively low cost. At the same time, there was a substantial clandestine importation of the rival Douay–Rheims New Testament of 1582, undertaken by exiled Catholics. This translation, though still derived from Tyndale, claimed to represent the text of the Latin Vulgate.[42]

In May 1601, King James VI of Scotland attended the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland at St Columba's Church in Burntisland, Fife, at which proposals were put forward for a new translation of the Bible into English.[43] Two years later, he ascended to the throne of England as James I.[44]

Considerations for a new version[edit]

The newly crowned King James convened the Hampton Court Conference in 1604. That gathering proposed a new English version in response to the perceived problems of earlier translations as detected by the Puritan faction of the Church of England. Here are three examples of problems the Puritans perceived with the Bishops and Great Bibles:

Instructions were given to the translators that were intended to limit the Puritan influence on this new translation. The Bishop of London added a qualification that the translators would add no marginal notes (which had been an issue in the Geneva Bible).[9] King James cited two passages in the Geneva translation where he found the marginal notes offensive to the principles of divinely ordained royal supremacy:[46] Exodus 1:19, where the Geneva Bible notes had commended the example of civil disobedience to the Egyptian Pharaoh showed by the Hebrew midwives, and also II Chronicles 15:16, where the Geneva Bible had criticized King Asa for not having executed his idolatrous 'mother', Queen Maachah (Maachah had actually been Asa's grandmother, but James considered the Geneva Bible reference as sanctioning the execution of his own mother Mary, Queen of Scots).[46] Further, the King gave the translators instructions designed to guarantee that the new version would conform to the ecclesiology of the Church of England.[9]Certain Greek and Hebrew words were to be translated in a manner that reflected the traditional usage of the church.[9] For example, old ecclesiastical words such as the word "church" were to be retained and not to be translated as "congregation".[9] The new translation would reflect the episcopal structure of the Church of England and traditional beliefs about ordained clergy.[9]

James' instructions included several requirements that kept the new translation familiar to its listeners and readers. The text of the Bishops' Bible would serve as the primary guide for the translators, and the familiar proper names of the biblical characters would all be retained. If the Bishops' Bible was deemed problematic in any situation, the translators were permitted to consult other translations from a pre-approved list: the Tyndale Bible, the Coverdale Bible, Matthew's Bible, the Great Bible, and the Geneva Bible. In addition, later scholars have detected an influence on the Authorized Version from the translations of Taverner's Bible and the New Testament of the Douay–Rheims Bible.[47] It is for this reason that the flyleaf of most printings of the Authorized Version observes that the text had been "translated out of the original tongues, and with the former translations diligently compared and revised, by His Majesty's special commandment." As the work proceeded, more detailed rules were adopted as to how variant and uncertain readings in the Hebrew and Greek source texts should be indicated, including the requirement that words supplied in English to 'complete the meaning' of the originals should be printed in a different type face.[48]

The task of translation was undertaken by 47 scholars, although 54 were originally approved.[10] All were members of the Church of England and all except Sir Henry Savile were clergy.[49] The scholars worked in six committees, two based in each of the University of Oxford, the University of Cambridge, and Westminster. The committees included scholars with Puritan sympathies, as well as high churchmen. Forty unbound copies of the 1602 edition of the Bishops' Bible were specially printed so that the agreed changes of each committee could be recorded in the margins.[50] The committees worked on certain parts separately and the drafts produced by each committee were then compared and revised for harmony with each other.[51] The scholars were not paid directly for their translation work, instead a circular letter was sent to bishops encouraging them to consider the translators for appointment to well-paid livings as these fell vacant.[49] Several were supported by the various colleges at Oxford and Cambridge, while others were promoted to bishoprics, deaneries and prebends through royal patronage.

The committees started work towards the end of 1604. King James VI and I, on 22 July 1604, sent a letter to Archbishop Bancroft asking him to contact all English churchmen requesting that they make donations to his project.

They had all completed their sections by 1608, the Apocrypha committee finishing first.[53] From January 1609, a General Committee of Review met at Stationers' Hall, London to review the completed marked texts from each of the six committees. The General Committee included John Bois, Andrew Downes and John Harmar, and others known only by their initials, including "AL" (who may be Arthur Lake), and were paid for their attendance by the Stationers' Company. John Bois prepared a note of their deliberations (in Latin) – which has partly survived in two later transcripts.[54] Also surviving of the translators' working papers are a bound-together set of marked-up corrections to one of the forty Bishops' Bibles—covering the Old Testament and Gospels,[55] and also a manuscript translation of the text of the Epistles, excepting those verses where no change was being recommended to the readings in the Bishops' Bible.[56] Archbishop Bancroft insisted on having a final say making fourteen further changes, of which one was the term "bishopricke" at Acts 1:20.[57]

Translation committees[edit]

- First Westminster Company, translated Genesis to 2 Kings: Lancelot Andrewes, John Overall, Hadrian à Saravia, Richard Clarke, John Layfield, Robert Tighe, Francis Burleigh, Geoffrey King, Richard Thomson, William Bedwell;

- First Cambridge Company, translated 1 Chronicles to the Song of Solomon: Edward Lively, John Richardson, Lawrence Chaderton, Francis Dillingham, Roger Andrewes, Thomas Harrison, Robert Spaulding, Andrew Bing;

- First Oxford Company, translated Isaiah to Malachi: John Harding, John Rainolds (or Reynolds), Thomas Holland, Richard Kilby, Miles Smith, Richard Brett, Daniel Fairclough, William Thorne;[58]

- Second Oxford Company, translated the Gospels, Acts of the Apostles, and the Book of Revelation: Thomas Ravis, George Abbot, Richard Eedes, Giles Tomson, Sir Henry Savile, John Peryn, Ralph Ravens, John Harmar, John Aglionby, Leonard Hutten;

- Second Westminster Company, translated the Epistles: William Barlow, John Spenser, Roger Fenton, Ralph Hutchinson, William Dakins, Michael Rabbet, Thomas Sanderson (who probably had already become Archdeacon of Rochester);

- Second Cambridge Company, translated the Apocrypha: John Duport, William Branthwaite, Jeremiah Radcliffe, Samuel Ward, Andrew Downes, John Bois, Robert Ward, Thomas Bilson, Richard Bancroft.[59]

Printing[edit]

The original printing of the Authorized Version was published by Robert Barker, the King's Printer, in 1611 as a complete folio Bible.[60] It was sold looseleaf for ten shillings, or bound for twelve.[61] Robert Barker's father, Christopher, had, in 1589, been granted by Elizabeth I the title of royal Printer,[62] with the perpetual Royal Privilege to print Bibles in England.[c] Robert Barker invested very large sums in printing the new edition, and consequently ran into serious debt,[63] such that he was compelled to sub-lease the privilege to two rival London printers, Bonham Norton and John Bill.[64] It appears that it was initially intended that each printer would print a portion of the text, share printed sheets with the others, and split the proceeds. Bitter financial disputes broke out, as Barker accused Norton and Bill of concealing their profits, while Norton and Bill accused Barker of selling sheets properly due to them as partial Bibles for ready money.[65]There followed decades of continual litigation, and consequent imprisonment for debt for members of the Barker and Norton printing dynasties,[65] while each issued rival editions of the whole Bible. In 1629 the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge successfully managed to assert separate and prior royal licences for Bible printing, for their own university presses—and Cambridge University took the opportunity to print revised editions of the Authorized Version in 1629,[66] and 1638.[67] The editors of these editions included John Bois and John Ward from the original translators. This did not, however, impede the commercial rivalries of the London printers, especially as the Barker family refused to allow any other printers access to the authoritative manuscript of the Authorized Version.[68]

Two editions of the whole Bible are recognized as having been produced in 1611, which may be distinguished by their rendering of Ruth 3:15;[69] the first edition reading "he went into the city", where the second reads "she went into the city";[70] these are known colloquially as the "He" and "She" Bibles.[71]

The original printing was made before English spelling was standardized, and when printers, as a matter of course, expanded and contracted the spelling of the same words in different places, so as to achieve an even column of text.[72] They set v for initial u and v, and u for u and v everywhere else. They used long ſ for non-final s.[73] The glyph j occurs only after i, as in the final letter in a Roman numeral. Punctuation was relatively heavy and differed from current practice. When space needed to be saved, the printers sometimes used ye for the (replacing the Middle English thorn, Þ, with the continental y), set ã for an or am (in the style of scribe's shorthand), and set & for and. On the contrary, on a few occasions, they appear to have inserted these words when they thought a line needed to be padded.[citation needed] Later printings regularized these spellings; the punctuation has also been standardized, but still varies from current usage norms.

The first printing used a blackletter typeface instead of a roman typeface, which itself made a political and a religious statement. Like the Great Bible and the Bishops' Bible, the Authorized Version was "appointed to be read in churches". It was a large folio volume meant for public use, not private devotion; the weight of the type mirrored the weight of establishment authority behind it.[citation needed] However, smaller editions and roman-type editions followed rapidly, e.g. quarto roman-type editions of the Bible in 1612.[74] This contrasted with the Geneva Bible, which was the first English Bible printed in a roman typeface (although black-letter editions, particularly in folio format, were issued later).

In contrast to the Geneva Bible and the Bishops' Bible, which had both been extensively illustrated, there were no illustrations at all in the 1611 edition of the Authorized Version, the main form of decoration being the historiated initial letters provided for books and chapters – together with the decorative title pages to the Bible itself, and to the New Testament.[citation needed]

In the Great Bible, readings derived from the Vulgate but not found in published Hebrew and Greek texts had been distinguished by being printed in smaller roman type.[75] In the Geneva Bible, a distinct typeface had instead been applied to distinguish text supplied by translators, or thought needful for English grammar but not present in the Greek or Hebrew; and the original printing of the Authorized Version used roman type for this purpose, albeit sparsely and inconsistently.[76] This results in perhaps the most significant difference between the original printed text of the King James Bible and the current text. When, from the later 17th century onwards, the Authorized Version began to be printed in roman type, the typeface for supplied words was changed to italics, this application being regularized and greatly expanded. This was intended to de-emphasize the words.[77]

The original printing contained two prefatory texts; the first was a formal Epistle Dedicatory to "the most high and mighty Prince" King James. Many British printings reproduce this, while most non-British printings do not.[citation needed]

The second preface was called Translators to the Reader, a long and learned essay that defends the undertaking of the new version. It observes the translators' stated goal, that they "never thought from the beginning that [they] should need to make a new translation, nor yet to make of a bad one a good one, ... but to make a good one better, or out of many good ones, one principal good one, not justly to be excepted against; that hath been our endeavour, that our mark." They also give their opinion of previous English Bible translations, stating, "We do not deny, nay, we affirm and avow, that the very meanest translation of the Bible in English, set forth by men of our profession, (for we have seen none of theirs [Catholics] of the whole Bible as yet) containeth the word of God, nay, is the word of God." As with the first preface, some British printings reproduce this, while most non-British printings do not. Almost every printing that includes the second preface also includes the first.[citation needed] The first printing contained a number of other apparatus, including a table for the reading of the Psalms at matins and evensong, and a calendar, an almanac, and a table of holy days and observances. Much of this material became obsolete with the adoption of the Gregorian calendar by Britain and its colonies in 1752, and thus modern editions invariably omit it.[citation needed]

So as to make it easier to know a particular passage, each chapter was headed by a brief précis of its contents with verse numbers. Later editors freely substituted their own chapter summaries, or omitted such material entirely.[citation needed] Pilcrow marks are used to indicate the beginnings of paragraphs except after the book of Acts.[78]

Authorized Version[edit]

The Authorized Version was meant to replace the Bishops' Bible as the official version for readings in the Church of England. No record of its authorization exists; it was probably effected by an order of the Privy Council, but the records for the years 1600 to 1613 were destroyed by fire in January 1618/19,[13] and it is commonly known as the Authorized Version in the United Kingdom. The King's Printer issued no further editions of the Bishops' Bible,[62] so necessarily the Authorized Version replaced it as the standard lectern Bible in parish church use in England.

In the 1662 Book of Common Prayer, the text of the Authorized Version finally supplanted that of the Great Bible in the Epistle and Gospel readings[79]—though the Prayer Book Psalter nevertheless continues in the Great Bible version.[80]

The case was different in Scotland, where the Geneva Bible had long been the standard church Bible. It was not until 1633 that a Scottish edition of the Authorized Version was printed—in conjunction with the Scots coronation in that year of Charles I.[81] The inclusion of illustrations in the edition raised accusations of Popery from opponents of the religious policies of Charles and William Laud, Archbishop of Canterbury. However, official policy favoured the Authorized Version, and this favour returned during the Commonwealth—as London printers succeeded in re-asserting their monopoly on Bible printing with support from Oliver Cromwell—and the "New Translation" was the only edition on the market.[82] F. F. Bruce reports that the last recorded instance of a Scots parish continuing to use the "Old Translation" (i.e. Geneva) as being in 1674.[83]

The Authorized Version's acceptance by the general public took longer. The Geneva Bible continued to be popular, and large numbers were imported from Amsterdam, where printing continued up to 1644 in editions carrying a false London imprint.[84] However, few if any genuine Geneva editions appear to have been printed in London after 1616, and in 1637 Archbishop Laud prohibited their printing or importation. In the period of the English Civil War, soldiers of the New Model Army were issued a book of Geneva selections called "The Soldiers' Bible".[85] In the first half of the 17th century the Authorized Version is most commonly referred to as "The Bible without notes", thereby distinguishing it from the Geneva "Bible with notes".[81] There were several printings of the Authorized Version in Amsterdam—one as late as 1715[86] which combined the Authorized Version translation text with the Geneva marginal notes;[87] one such edition was printed in London in 1649. During the Commonwealth a commission was established by Parliament to recommend a revision of the Authorized Version with acceptably Protestant explanatory notes,[84] but the project was abandoned when it became clear that these would nearly double the bulk of the Bible text. After the English Restoration, the Geneva Bible was held to be politically suspect and a reminder of the repudiated Puritan era.[citation needed]Furthermore, disputes over the lucrative rights to print the Authorized Version dragged on through the 17th century, so none of the printers involved saw any commercial advantage in marketing a rival translation.[citation needed] The Authorized Version became the only current version circulating among English-speaking people.

A small minority of critical scholars were slow to accept the latest translation. Hugh Broughton, who was the most highly regarded English Hebraist of his time but had been excluded from the panel of translators because of his utterly uncongenial temperament,[88] issued in 1611 a total condemnation of the new version.[89] He especially criticized the translators' rejection of word-for-word equivalence and stated that "he would rather be torn in pieces by wild horses than that this abominable translation (KJV) should ever be foisted upon the English people".[90] Walton's London Polyglot of 1657 disregards the Authorized Version (and indeed the English language) entirely.[91] Walton's reference text throughout is the Vulgate. The Vulgate Latin is also found as the standard text of scripture in Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan of 1651,[92] indeed Hobbes gives Vulgate chapter and verse numbers (e.g., Job 41:24, not Job 41:33) for his head text. In Chapter 35: 'The Signification in Scripture of Kingdom of God', Hobbes discusses Exodus 19:5, first in his own translation of the 'Vulgar Latin', and then subsequently as found in the versions he terms "... the English translation made in the beginning of the reign of King James", and "The Geneva French" (i.e. Olivétan). Hobbes advances detailed critical arguments why the Vulgate rendering is to be preferred. For most of the 17th century the assumption remained that, while it had been of vital importance to provide the scriptures in the vernacular for ordinary people, nevertheless for those with sufficient education to do so, Biblical study was best undertaken within the international common medium of Latin. It was only in 1700 that modern bilingual Bibles appeared in which the Authorized Version was compared with counterpart Dutch and French Protestant vernacular Bibles.[93]

In consequence of the continual disputes over printing privileges, successive printings of the Authorized Version were notably less careful than the 1611 edition had been—compositors freely varying spelling, capitalization and punctuation[94]—and also, over the years, introducing about 1,500 misprints (some of which, like the omission of "not" from the commandment "Thou shalt not commit adultery" in the "Wicked Bible",[95] became notorious). The two Cambridge editions of 1629 and 1638 attempted to restore the proper text—while introducing over 200 revisions of the original translators' work, chiefly by incorporating into the main text a more literal reading originally presented as a marginal note.[96] A more thoroughly corrected edition was proposed following the Restoration, in conjunction with the revised 1662 Book of Common Prayer, but Parliament then decided against it.[citation needed]

By the first half of the 18th century, the Authorized Version was effectively unchallenged as the sole English translation in current use in Protestant churches,[11] and was so dominant that the Catholic Church in England issued in 1750 a revision of the 1610 Douay–Rheims Bible by Richard Challoner that was very much closer to the Authorized Version than to the original.[97] However, general standards of spelling, punctuation, typesetting, capitalization and grammar had changed radically in the 100 years since the first edition of the Authorized Version, and all printers in the market were introducing continual piecemeal changes to their Bible texts to bring them into line with current practice—and with public expectations of standardized spelling and grammatical construction.[98]

Over the course of the 18th century, the Authorized Version supplanted the Hebrew, Greek and the Latin Vulgate as the standard version of scripture for English speaking scholars and divines, and indeed came to be regarded by some as an inspired text in itself—so much so that any challenge to its readings or textual base came to be regarded by many as an assault on Holy Scripture.[99]

In the 18th century there was a serious shortage of Bibles in the American colonies. To meet the demand various printers, beginning with Samuel Kneeland in 1752, printed the King James Bible without authorization from the Crown. To avert prosecution and detection of an unauthorized printing they would include the royal insignia on the title page, using the same materials in its printing as the authorized version was produced from, which were imported from England.[100][101]

Standard text of 1769[edit]

By the mid-18th century the wide variation in the various modernized printed texts of the Authorized Version, combined with the notorious accumulation of misprints, had reached the proportion of a scandal, and the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge both sought to produce an updated standard text. First of the two was the Cambridge edition of 1760, the culmination of 20 years' work by Francis Sawyer Parris,[102] who died in May of that year. This 1760 edition was reprinted without change in 1762[103] and in John Baskerville's fine folio edition of 1763.[104] This was effectively superseded by the 1769 Oxford edition, edited by Benjamin Blayney,[105] though with comparatively few changes from Parris's edition; but which became the Oxford standard text, and is reproduced almost unchanged in most current printings.[106] Parris and Blayney sought consistently to remove those elements of the 1611 and subsequent editions that they believed were due to the vagaries of printers, while incorporating most of the revised readings of the Cambridge editions of 1629 and 1638, and each also introducing a few improved readings of their own. They undertook the mammoth task of standardizing the wide variation in punctuation and spelling of the original, making many thousands of minor changes to the text. In addition, Blayney and Parris thoroughly revised and greatly extended the italicization of "supplied" words not found in the original languages by cross-checking against the presumed source texts. Blayney seems to have worked from the 1550 Stephanus edition of the Textus Receptus, rather than the later editions of Theodore Beza that the translators of the 1611 New Testament had favoured; accordingly the current Oxford standard text alters around a dozen italicizations where Beza and Stephanus differ.[107] Like the 1611 edition, the 1769 Oxford edition included the Apocrypha, although Blayney tended to remove cross-references to the Books of the Apocrypha from the margins of their Old and New Testaments wherever these had been provided by the original translators. It also includes both prefaces from the 1611 edition. Altogether, the standardization of spelling and punctuation caused Blayney's 1769 text to differ from the 1611 text in around 24,000 places.[108]

The 1611 and 1769 texts of the first three verses from I Corinthians 13 are given below.

There are a number of superficial edits in these three verses: 11 changes of spelling, 16 changes of typesetting (including the changed conventions for the use of u and v), three changes of punctuation, and one variant text—where "not charity" is substituted for "no charity" in verse two, in the erroneous belief that the original reading was a misprint.

A particular verse for which Blayney's 1769 text differs from Parris's 1760 version is Matthew 5:13, where Parris (1760) has

Blayney (1769) changes 'lost his savour' to 'lost its savour', and troden to trodden.

For a period, Cambridge continued to issue Bibles using the Parris text, but the market demand for absolute standardization was now such that they eventually adapted Blayney's work but omitted some of the idiosyncratic Oxford spellings. By the mid-19th century, almost all printings of the Authorized Version were derived from the 1769 Oxford text—increasingly without Blayney's variant notes and cross references, and commonly excluding the Apocrypha.[109] One exception to this was a scrupulous original-spelling, page-for-page, and line-for-line reprint of the 1611 edition (including all chapter headings, marginalia, and original italicization, but with Roman type substituted for the black letter of the original), published by Oxford in 1833.[d] Another important exception was the 1873 Cambridge Paragraph Bible, thoroughly revised, modernized and re-edited by F. H. A. Scrivener, who for the first time consistently identified the source texts underlying the 1611 translation and its marginal notes.[111] Scrivener, like Blayney, opted to revise the translation where he considered the judgement of the 1611 translators had been faulty.[112] In 2005, Cambridge University Press released its New Cambridge Paragraph Biblewith Apocrypha, edited by David Norton, which followed in the spirit of Scrivener's work, attempting to bring spelling to present-day standards. Norton also innovated with the introduction of quotation marks, while returning to a hypothetical 1611 text, so far as possible, to the wording used by its translators, especially in the light of the re-emphasis on some of their draft documents.[113] This text has been issued in paperback by Penguin Books.[114]

From the early 19th century the Authorized Version has remained almost completely unchanged—and since, due to advances in printing technology, it could now be produced in very large editions for mass sale, it established complete dominance in public and ecclesiastical use in the English-speaking Protestant world. Academic debate through that century, however, increasingly reflected concerns about the Authorized Version shared by some scholars: (a) that subsequent study in oriental languages suggested a need to revise the translation of the Hebrew Bible—both in terms of specific vocabulary, and also in distinguishing descriptive terms from proper names; (b) that the Authorized Version was unsatisfactory in translating the same Greek words and phrases into different English, especially where parallel passages are found in the synoptic gospels; and (c) in the light of subsequent ancient manuscript discoveries, the New Testament translation base of the Greek Textus Receptus could no longer be considered to be the best representation of the original text.[115]

Responding to these concerns, the Convocation of Canterbury resolved in 1870 to undertake a revision of the text of the Authorized Version, intending to retain the original text "except where in the judgement of competent scholars such a change is necessary". The resulting revision was issued as the Revised Version in 1881 (New Testament), 1885 (Old Testament) and 1894 (Apocrypha); but, although it sold widely, the revision did not find popular favour, and it was only reluctantly in 1899 that Convocation approved it for reading in churches.[116]

By the early 20th century, editing had been completed in Cambridge's text, with at least 6 new changes since 1769, and the reversing of at least 30 of the standard Oxford readings. The distinct Cambridge text was printed in the millions, and after the Second World War "the unchanging steadiness of the KJB was a huge asset."[117]

The Authorized Version maintained its effective dominance throughout the first half of the 20th century. New translations in the second half of the 20th century displaced its 250 years of dominance (roughly 1700 to 1950),[118] but groups do exist—sometimes termed the King James Only movement—that distrust anything not in agreement with the Authorized Version.[119]

Editorial criticism[edit]

F. H. A. Scrivener and D. Norton have both written in detail on editorial variations which have occurred through the history of the publishing of the Authorized Version from 1611 to 1769. In the 19th century, there were effectively three main guardians of the text. Norton identified five variations among the Oxford, Cambridge and London (Eyre and Spottiswoode) texts of 1857, such as the spelling of "farther" or "further" at Matthew 26:39.[120]

In the 20th century, variation between the editions was reduced to comparing the Cambridge to the Oxford. Distinctly identified Cambridge readings included "or Sheba",[121]"sin",[122] "clifts",[123] "vapour",[124] "flieth",[125] "further"[126] and a number of other references. In effect the Cambridge was considered the current text in comparison to the Oxford.[127] These are instances where both Oxford and Cambridge have now diverged from Blayney's 1769 Edition. The distinctions between the Oxford and Cambridge editions have been a major point in the Bible version debate,[128] and a potential theological issue,[129] particularly in regard to the identification of the Pure Cambridge Edition.[130]

Cambridge University Press introduced a change at 1 John 5:8[131] in 1985, reversing its longstanding tradition of printing the word "spirit" in lower case by using a capital letter "S".[132] A Rev. Hardin of Bedford, Pennsylvania, wrote a letter to Cambridge inquiring about this verse, and received a reply on 3 June 1985 from the Bible Director, Jerry L. Hooper, admitting that it was a "matter of some embarrassment regarding the lower case 's' in Spirit".[133]

Literary attributes[edit]

Translation[edit]

Like Tyndale's translation and the Geneva Bible, the Authorized Version was translated primarily from Greek, Hebrew and Aramaic texts, although with secondary reference both to the Latin Vulgate, and to more recent scholarly Latin versions; two books of the Apocrypha were translated from a Latin source. Following the example of the Geneva Bible, words implied but not actually in the original source were distinguished by being printed in distinct type (albeit inconsistently), but otherwise the translators explicitly rejected word-for-word equivalence.[134] F. F. Bruce gives an example from Romans Chapter 5:[135]

The English terms "rejoice" and "glory" are translated from the same word καυχώμεθα (kaukhṓmetha) in the Greek original. In Tyndale, Geneva and the Bishops' Bibles, both instances are translated "rejoice". In the Douay–Rheims New Testament, both are translated "glory". Only in the Authorized Version does the translation vary between the two verses.

In obedience to their instructions, the translators provided no marginal interpretation of the text, but in some 8,500 places a marginal note offers an alternative English wording.[136] The majority of these notes offer a more literal rendering of the original, introduced as "Heb", "Chal" (Chaldee, referring to Aramaic), "Gr" or "Lat". Others indicate a variant reading of the source text (introduced by "or"). Some of the annotated variants derive from alternative editions in the original languages, or from variant forms quoted in the fathers. More commonly, though, they indicate a difference between the literal original language reading and that in the translators' preferred recent Latin versions: Tremelliusfor the Old Testament, Junius for the Apocrypha, and Beza for the New Testament.[137] At thirteen places in the New Testament[138][139] a marginal note records a variant reading found in some Greek manuscript copies; in almost all cases reproducing a counterpart textual note at the same place in Beza's editions.[140] A few more extensive notes clarify Biblical names and units of measurement or currency. Modern reprintings rarely reproduce these annotated variants—although they are to be found in the New Cambridge Paragraph Bible. In addition, there were originally some 9,000 scriptural cross-references, in which one text was related to another. Such cross-references had long been common in Latin Bibles, and most of those in the Authorized Version were copied unaltered from this Latin tradition. Consequently the early editions of the KJV retain many Vulgate verse references—e.g. in the numbering of the Psalms.[141] At the head of each chapter, the translators provided a short précis of its contents, with verse numbers; these are rarely included in complete form in modern editions.

Also in obedience to their instructions, the translators indicated 'supplied' words in a different typeface; but there was no attempt to regularize the instances where this practice had been applied across the different companies; and especially in the New Testament, it was used much less frequently in the 1611 edition than would later be the case.[76] In one verse, 1 John 2:23, an entire clause was printed in roman type (as it had also been in the Great Bible and Bishop's Bible);[142] indicating a reading then primarily derived from the Vulgate, albeit one for which the later editions of Beza had provided a Greek text.[143]

In the Old Testament the translators render the Tetragrammaton (YHWH) by "the LORD" (in later editions in small capitals as LORD),[e] or "the LORD God" (for YHWH Elohim, יהוה אלהים),[f] except in four places by "IEHOVAH".[144] However, if the Tetragrammaton occurs with the Hebrew word adonai (Lord) then it is rendered not as the "Lord LORD" but as the "Lord God".[145] In later editions it appears as "Lord god", with "god" in small capitals, indicating to the reader that God's name appears in the original Hebrew.

Old Testament[edit]

For the Old Testament, the translators used a text originating in the editions of the Hebrew Rabbinic Bible by Daniel Bomberg (1524/5),[146][failed verification] but adjusted this to conform to the Greek LXX or Latin Vulgate in passages to which Christian tradition had attached a Christological interpretation.[147] For example, the Septuagint reading "They pierced my hands and my feet" was used in Psalm 22:16[148] (vs. the Masoretes' reading of the Hebrew "like lions my hands and feet"[149]). Otherwise, however, the Authorized Version is closer to the Hebrew tradition than any previous English translation—especially in making use of the rabbinic commentaries, such as Kimhi, in elucidating obscure passages in the Masoretic Text;[150] earlier versions had been more likely to adopt LXX or Vulgate readings in such places. Following the practice of the Geneva Bible, the books of 1 Esdras and 2 Esdras in the medieval Vulgate Old Testament were renamed 'Ezra' and 'Nehemiah'; 3 Esdras and 4 Esdras in the Apocrypha being renamed '1 Esdras' and '2 Esdras'.

New Testament[edit]