As such is the word in arithmetic it is why physics? The word to mathematics is in the number of explanation as noted to addition. The balance of what is in the continue to engage the ongoing as arithmetic in named it remains, the day to earth to atmosphere at environment.

What is the avenue as the balance has been named by so many that the public at-large has become an economy of government. To explain the caveman at the cave I must account for the balance at a keel in our history for this word to arithmetic to balance at keel in the physics of Cantore Arithmetic.

History has brought at obvious the “Seven deadly sins” to never speak of the Nostradamus Effect. This boom to what is the why in the Revelations of the King James Version must be accounted for and as such the problem must have residence as religion is also a powerful economy too. This atmospheric effect has had to go from the T-Rex to now as the Jurassic Period has had an Age to Earth History making the effect itself important enough to understand stop.

Should the ‘Seven Deadly Sins’ not have been respected and as the public at-large grew to the power of this earth than the religions of this world would have had to have had a quote, “be careful” for the Grand Canyon is of sediment?

To engage the repeat in a constant it is not the quote unquote if that brings residence but the warning of what caused death. Should the public at-large not have listened that we would be at today with all the balance without a keel and the weather would respond with what is atmosphere as an effect.

An important addition: The ‘Plus’ sign must have provided at provision.

Seven deadly sins

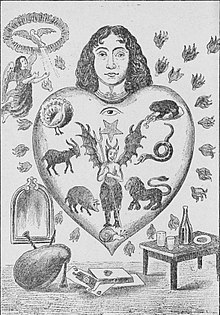

The seven deadly sins, also known as the capital vices or cardinal sins, is a grouping and classification of vices within Christian teachings,[1] although they are not mentioned in the Bible. Behaviours or habits are classified under this category if they directly give rise to other immoralities.[2] According to the standard list, they are pride, greed, wrath, envy, lust, gluttony and sloth,[2] which are contrary to the seven heavenly virtues.

This classification originated with the Desert Fathers, especially Evagrius Ponticus, who identified seven or eight evil thoughts or spirits to be overcome.[3] Evagrius' pupil John Cassian with his book The Institutes brought the classification to Europe,[4] where it became fundamental to Catholic confessional practices as documented in penitential manuals, sermons such as "The Parson's Tale" from Chaucer's Canterbury Tales and artworks such as Dante's Purgatory where the penitents of Mount Purgatory are grouped and penanced according to their worst sin. The Catholic Church used the best of the deadly sins to help people curb their evil inclinations before they could fester. Teachers especially focused on pride, which is thought to be the sin that severs the soul from grace[5] and is the very essence of evil, and greed, both of which underlie the other sins. The seven deadly sins are discussed in treatises and depicted in paintings and sculpture decorations on Catholic churches as well as older textbooks.[1] The seven deadly sins, along with the sins against the Holy Ghost and the sins that cry to Heaven for vengeance, are taught especially in Western Christian traditions as things to be deplored.[6]

History

Greco-Roman antecedents

The seven deadly sins as we know them had pre-Christian Greek and Roman precedents. Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics lists several excellences or virtues. Aristotle argues that each positive quality represents a golden mean between two extremes, each of which is a vice. Courage, for example, is the virtue of facing fear and danger; excess courage is recklessness, while deficient courage is cowardice. Aristotle lists several virtues, such as courage, temperance or self-control, generosity, greatness of soul or magnanimity, measured anger, friendship, and wit or charm.

Roman writers such as Horace extolled virtues, and they listed and warned against vices. His first epistles say that "to flee vice is the beginning of virtue and to have got rid of folly is the beginning of wisdom."[7]

Origin of the currently recognized seven deadly sins

The modern concept of the seven deadly sins is linked to the works of the fourth-century monk Evagrius Ponticus, who listed eight evil thoughts in Greek as follows:[8][9]

- Γαστριμαργία (gastrimargia) gluttony

- Πορνεία (porneia) prostitution, fornication

- Φιλαργυρία (philargyria) avarice (greed)

- Λύπη (lypē) sadness, rendered in the Philokalia as envy, sadness at another's good fortune

- Ὀργή (orgē) wrath

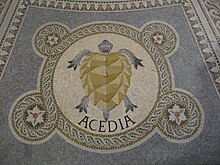

- Ἀκηδία (akēdia) acedia, rendered in the Philokalia as dejection

- Κενοδοξία (kenodoxia) boasting

- Ὑπερηφανία (hyperēphania) pride, sometimes rendered as self-overestimation, arrogance, or grandiosity[10]

They were translated into the Latin of Western Christianity in many writings of John Cassian,[11][12] thus becoming part of the Western tradition's spiritual pietas or Catholic devotions as follows:[13]

- Gula (gluttony)

- Luxuria/Fornicatio (lust, fornication)

- Avaritia (avarice/greed)

- Tristitia (sorrow/despair/despondency)

- Ira (wrath)

- Acedia (sloth)

- Vanagloria (vainglory)

- Superbia (pride, hubris)

These "evil thoughts" can be categorized into three types:[13]

- lustful appetite (gluttony, fornication, and avarice)

- irascibility (wrath)

- mind corruption (vainglory, sorrow, pride, and discouragement)

In AD 590, Pope Gregory I revised the list to form a more common list.[14] Gregory combined tristitia with acedia and vanagloria with superbia, adding envy, which is invidia in Latin.[15][16] Gregory's list became the standard list of sins. Thomas Aquinas uses and defends Gregory's list in his Summa Theologica, although he calls them the "capital sins" because they are the head and form of all the others.[17] Christian denominations, such as the Anglican Communion,[18] Lutheran Church,[19] and Methodist Church,[20][21] still retain this list, and modern evangelists such as Billy Graham have explicated the seven deadly sins.[22]

Historical and modern definitions, views, and associations

Most of the seven deadly sins are defined by Dante Alighieri (c. 1264–1321) as perverse or corrupt versions of love; lust, gluttony, and greed are all excessive or disordered love of good things; and wrath, envy, and pride are perverted love directed toward others' harm. The sole exception is sloth, which is a deficiency of love.[23] In the seven deadly sins are seven ways of eternal death.[5] The deadly sins are generally associated with pride which is thought to be the father of all sins in order to help the others—which appears from lust to envy.

Lust

Lust or lechery (Latin: luxuria (carnal)) is intense longing. It is usually thought of as intense or unbridled sexual desire,[24] which may lead to fornication (including adultery), rape, bestiality, and other sinful and sexual acts; oftentimes, however, it could also mean other forms of unbridled desire, such as for money, or power. Henry Edward Manning explains that the impurity of lust transforms one into "a slave of the devil".[5]

Dante defined lust as the disordered love for individuals.[25] It is generally thought to be the least serious capital sin,[23][26] as it is an abuse of a faculty that humans share with animals and sins of the flesh are less grievous than spiritual sins.[27] In Dante's Purgatorio, the penitent walks within flames to purge himself of lustful thoughts and feelings. Unforgiven souls guilty of lust are also eternally blown about in restless hurricane-like winds symbolic of their own lack of self-control of their lustful passions in earthly life and as shown in Dante's Inferno.[28]

Gluttony

Gluttony (Latin: gula) is the overindulgence and overconsumption of anything to the point of waste. The word derives from the Latin gluttire, meaning to gulp down or swallow.[citation needed] One reason for its condemnation is that gorging the prosperous may leave the needy hungry.[29]

Medieval church leaders such as Thomas Aquinas took a more expansive view of gluttony,[29] arguing that it could also include an obsessive anticipation of meals and over-indulgence in delicacies and costly foods.[30] Aquinas also listed five forms of gluttony:

- Laute – eating too expensively

- Studiose – eating too daintily

- Nimis – eating too much

- Praepropere – eating too soon

- Ardenter – eating too eagerly

Ardenter is often considered the most serious of these, since it is a passion for a mere earthly pleasure, which can make the committer eat impulsively or even reduce the goals of life to mere eating and drinking; for example, Esau sold his birthright for a mess of pottage with a "profane person ... who, for a morsel of meat sold his birthright" and later stated that "he found no place for repentance, though he sought it carefully, with tears".[Gen 25:30]

Greed

Greed (Latin: avaritia), also known as avarice, cupidity, or covetousness, is a sin of desire like lust and gluttony. However, greed (as seen by the Church) is applied to an artificial, rapacious desire as well as the pursuit of material possessions. Thomas Aquinas wrote: "Greed is a sin against God, just as all mortal sins, in as much as man condemns things eternal for the sake of temporal things." In Dante's Purgatory, the penitents are bound and laid face down on the ground for having concentrated excessively on earthly thoughts. Hoardingof materials or objects, theft, and robbery, especially by means of violence, trickery, or manipulation of authority, are all actions that may be inspired by greed. Such misdeeds can include simony, where one attempts to purchase or sell sacraments, including Holy Ordersand, therefore, positions of authority in the Church hierarchy.[citation needed]

In the words of Henry Edward, avarice "plunges a man deep into the mire of this world, so that he makes it to be his god".[5]

As defined outside Christian writings, greed is an inordinate desire to acquire or possess more than one needs, especially with respect to material wealth.[31] Like pride, it can lead to evil.[2]

Sloth

Sloth (Latin: tristitia or acedia ("without care")) refers to a peculiar jumble of notions, dating from antiquity and including mental, spiritual, pathological, and physical states.[32] It may be defined as absence of interest or habitual disinclination to exertion.[33]

In his Summa Theologica, Saint Thomas Aquinas defined sloth as "sorrow about spiritual good".[2]

The scope of sloth is wide.[32] Spiritually, acedia first referred to an affliction attending religious persons, especially monks, wherein they became indifferent to their duties and obligations to God. Mentally, acedia has a number of distinctive components; the most important of these is affectlessness, a lack of any feeling about self or other, a mind-state that gives rise to boredom, rancor, apathy, and a passive inert or sluggish mentation. Physically, acedia is fundamentally associated with a cessation of motion and an indifference to work; it finds expression in laziness, idleness, and indolence.[32]

Sloth includes ceasing to utilize the seven gifts of grace given by the Holy Spirit (Wisdom, Understanding, Counsel, Knowledge, Piety, Fortitude, and Fear of the Lord); such disregard may lead to the slowing of spiritual progress towards eternal life, the neglect of manifold duties of charity towards the neighbor, and animosity towards those who love God.[5]

Sloth has also been defined as a failure to do things that one should do. By this definition, evil exists when "good" people fail to act.

Edmund Burke (1729–1797) wrote in Present Discontents (II. 78): "No man, who is not inflamed by vain-glory into enthusiasm, can flatter himself that his single, unsupported, desultory, unsystematic endeavours are of power to defeat the subtle designs and united Cabals of ambitious citizens. When bad men combine, the good must associate; else they will fall, one by one, an unpitied sacrifice in a contemptible struggle."

Unlike the other seven deadly sins, which are sins of committing immorality, sloth is a sin of omitting responsibilities. It may arise from any of the other capital vices; for example, a son may omit his duty to his father through anger. The state and habit of sloth is a mortal sin, while the habit of the soul tending towards the last mortal state of sloth is not mortal in and of itself except under certain circumstances.[5]

Emotionally, and cognitively, the evil of acedia finds expression in a lack of any feeling for the world, for the people in it, or for the self. Acedia takes form as an alienation of the sentient self first from the world and then from itself. The most profound versions of this condition are found in a withdrawal from all forms of participation in or care for others or oneself, but a lesser yet more noisome element was also noted by theologians. Gregory the Great asserted that, "from tristitia, there arise malice, rancour, cowardice, [and] despair". Chaucer also dealt with this attribute of acedia, counting the characteristics of the sin to include despair, somnolence, idleness, tardiness, negligence, indolence, and wrawnesse, the last variously translated as "anger" or better as "peevishness". For Chaucer, human's sin consists of languishing and holding back, refusing to undertake works of goodness because, he/she tells him/herself, the circumstances surrounding the establishment of good are too grievous and too difficult to suffer. Acedia in Chaucer's view is thus the enemy of every source and motive for work.[34]

Sloth subverts the livelihood of the body, taking no care for its day-to-day provisions, and slows down the mind, halting its attention to matters of great importance. Sloth hinders the man in his righteous undertakings and thus becomes a terrible source of human's undoing.[34]

In his Purgatorio, Dante portrayed the penance for acedia as running continuously at top speed. He describes acedia as the "failure to love God with all one's heart, all one's mind and all one's soul". To him, it was the "middle sin", the only one characterised by an absence or insufficiency of love.[citation needed]

Wrath

Wrath (ira) can be defined as uncontrolled feelings of anger, rage, and even hatred. Wrath often reveals itself in the wish to seek vengeance.[35] In its purest form, wrath presents with injury, violence, and hate that may provoke feuds that can go on for centuries. Wrath may persist long after the person who did another grievous wrong dies. Feelings of wrath can manifest in different ways, including impatience, hateful misanthropy, revenge, and self-destructive behavior, such as drug abuse, or Suicide.[original research?]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church, the neutral act of anger becomes the sin of wrath when it is directed against an innocent person, when it is unduly strong or long-lasting, or when it desires excessive punishment. "If anger reaches the point of a deliberate desire to kill or seriously wound a neighbor, it is gravely against charity; it is a mortal sin." (CCC 2302) Hatred is the sin of desiring that someone else may suffer misfortune or evil and is a mortal sin when one desires grave harm (CCC 2302–03).

People feel angry when they sense that they or someone they care about has been offended, when they are certain about the nature and cause of the angering event, when they are certain someone else is responsible, and when they feel that they can still influence the situation or cope with it.[36]

In her introduction to Purgatory, Dorothy L. Sayers describes wrath as "love of justice perverted to revenge and spite".[35] In accordance with Henry Edward, angry people are "slaves to themselves".[5]

Envy

Envy (invidia) is characterized by an insatiable desire like greed and lust. It can be described as a sad or resentful covetousness towards the traits or possessions of someone else. It arises from vainglory[37] and severs a man from his neighbor.[5]

Malicious envy is similar to jealousy in that they both feel discontent towards someone's traits, status, abilities, or rewards. A difference is that the envious also desire the entity and covet it. Envy can be directly related to the Ten Commandments, specifically, "Neither shall you covet ... anything that belongs to your neighbour"—a statement that may also be related to greed. Dante defined envy as "a desire to deprive other men of theirs". In Dante's Purgatory, the punishment for the envious is to have their eyes sewn shut with wire because they gained sinful pleasure from seeing others brought low. According to St. Thomas Aquinas, the struggle aroused by envy has three stages: during the first stage, the envious person attempts to lower another's reputation; in the middle stage, the envious person receives either "joy at another's misfortune" (if he succeeds in defaming the other person) or "grief at another's prosperity" (if he fails); and the third stage is hatred because "sorrow causes hatred".[38]

Envy is said to be the motivation behind Cain murdering his brother Abel, as Cain envied Abel because God favored Abel's sacrifice over Cain's.

Bertrand Russell said that envy was one of the most potent causes of unhappiness,[39][page needed] bringing sorrow to committers of envy, while giving them the urge to inflict pain upon others.

According to the most widely accepted views, only pride weighs down the soul more than envy among the capital sins. Like pride, envy has been associated directly with the devil, for Wisdom 2:24 states: "the envy of the devil brought death to the world".[37]

Pride

Pride (superbia) is considered the original and most serious of the seven deadly sins on almost every list. It is the most angelical or demonic out of them.[40] It is also thought to be the source of the other capital sins, known as hubris (from Ancient Greek ὕβρις) or futility. It is identified as dangerously corrupt selfishness, the putting of one's own desires, urges, wants, and whims before the welfare of other people.

In even more destructive cases, it is irrationally believing that one is essentially and necessarily better, superior, or more important than others, failing to acknowledge the accomplishments of others and excessive admiration of the personal image or self (especially forgetting one's own lack of divinity and refusing to acknowledge one's own limits, faults, or wrongs as a human being).

Pride has been labeled the father of all sins and has been deemed the devil's most prominent trait. C.S. Lewis writes in Mere Christianity that pride is the "anti-God" state, the position in which the ego and the self are directly opposed to God: "Unchastity, anger, greed, drunkenness and all that, are mere fleabites in comparison: it was through Pride that the devil became the devil: Pride leads to every other vice: it is the complete anti-God state of mind."[41] Pride is understood to sever the spirit from God, as well as His life-and-grace-giving Presence.[5]

One can be prideful for different reasons. Author Ichabod Spencer states that "spiritual pride is the worst kind of pride, if not worst snare of the devil. The heart is particularly deceitful on this one thing."[42] Jonathan Edwards said: "remember that pride is the worst viper that is in the heart, the greatest disturber of the soul's peace and sweet communion with Christ; it was the first sin that ever was and lies lowest in the foundation of Satan's whole building and is the most difficultly rooted out and is the most hidden, secret and deceitful of all lusts and often creeps in, insensibly, into the midst of religion and sometimes under the disguise of humility."[43]

In Ancient Athens, hubris was considered one of the greatest crimes and was used to refer to insolent contempt that can cause one to use violence to shame the victim. This sense of hubris could also characterize rape.[44] Aristotle defined hubris as shaming the victim merely for the committer's own gratification instead of anything that happened to the committer or might happen to the committer.[45][46][47] The word's connotation changed somewhat over time, with some additional emphasis towards a gross overestimation of one's abilities.

The term has been used to analyze and make sense of the actions of contemporary heads of government by Ian Kershaw (1998), Peter Beinart (2010) and in a much more physiological manner by David Owen (2012). In this context, the term has been used to describe how certain leaders seem to become irrationally self-confident in their own abilities, when put to positions of immense power and increasingly reluctant to listen to the advice of others and progressively more impulsive in their actions.[48] Dante's definition of pride was "love of self perverted to hatred and contempt for one's neighbor". Pride is generally associated with an absence of humility.[49][50]

According to the Sirach's author's wording, the heart of a proud man is "like a partridge in its cage acting as a decoy; like a spy he watches for your weaknesses. He changes good things into evil, he lays his traps. Just as a spark sets coals on fire, the wicked man prepares his snares in order to draw blood. Beware of the wicked man for he is planning evil. He might dishonor you forever." In another chapter, he says that "the acquisitive man is not content with what he has, wicked injustice shrivels the heart."

Benjamin Franklin said "In reality there is, perhaps no one of our natural passions so hard to subdue as pride. Disguise it, struggle with it, stifle it, mortify it as much as one pleases, it is still alive and will every now and then peep out and show itself; you will see it, perhaps, often in this history. For even if I could conceive that I had completely overcome it, I should probably be proud of my humility."[51] Joseph Addison states that "There is no passion that steals into the heart more imperceptibly and covers itself under more disguises than pride."[52]

The proverb "pride goeth [goes] before destruction, a haughty spirit before a fall" (also wrote as "pride goeth before the fall"; from the biblical Book of Proverbs, 16:18) is thought to sum up the modern use of pride. Pride is also referred to as "pride that blinds," as it often causes a committer of pride to act in foolish ways that belie common sense.[48] In other words, the modern definition may be thought of as "that pride that goes just before the fall." In his two-volume biography of Adolf Hitler, historian Ian Kershaw uses both "hubris" and "nemesis" as titles. The first volume Hubris[53] describes Hitler's early life and rise to political power. The second volume Nemesis[54] gives details of Hitler's role in the Second World War and concludes with his fall and suicide in 1945.

Much of the 10th and part of 11th chapter of the Book of Sirach discusses and advises about pride, hubris, and who is rationally worthy of honor. It goes:

In Jacob Bidermann's medieval miracle play Cenodoxus, pride is the deadliest of the seven deadly sins and leads directly to the damnation of the titulary famed Parisian doctor. In Dante's Divine Comedy, the penitents are burdened with stone slabs on their necks to keep their heads bowed.

Historical sins

Acedia

Acedia (Latin, acedia "without care"[32]) (from Greek ἀκηδία) is the neglect to take care of something that one should do. It is translated to apathetic listlessness; depression without joy. It is related to melancholy; acedia describes the behaviour and melancholy suggests the emotion producing it. In early Christian thought, the lack of joy was regarded as a willful refusal to enjoy the goodness of God. By contrast, apathy was considered a refusal to help others in time of need.

Acēdia is negative form of the Greek term κηδεία (Kēdeia), which has a more restricted usage. 'Kēdeia' refers specifically to spousal love and respect for the dead.[55] The positive term 'kēdeia' thus indicates love for one's family, even through death. It also indicates love for those outside one's immediate family, specifically forming a new family with one's "beloved". Seen in this way, acēdia indicates a rejection of familial love. Nonetheless, the meaning of acēdia is far more broad, signifying indifference to everything one experiences.

Pope Gregory combined this with tristitia into sloth for his list. When Thomas Aquinas described acedia in his interpretation of the list, he described it as an "uneasiness of the mind", being a progenitor for lesser sins such as restlessness and instability. Dante refined this definition further, describing acedia as the "failure to love God with all one's heart, all one's mind and all one's soul". To him, it was the "middle sin", the only one characterised by an absence or insufficiency of love.[citation needed]

Acedia is currently defined in the Catechism of the Catholic Church as spiritual sloth, believing spiritual tasks to be too difficult. In the fourth century, Christian monks believed that acedia was primarily caused by a state of melancholia that caused spiritual detachment instead of laziness.[56]

Vainglory

Vainglory (Latin, vanagloria) is unjustified boasting. Pope Gregory viewed it as a form of pride, so he folded vainglory into pride for his listing of sins.[15] According to Aquinas, it is the progenitor of envy.[37]

The Latin term gloria roughly means boasting, although its English cognate glory has come to have an exclusively positive meaning. Historically, the term vain roughly meant futile (a meaning retained in the modern expression "in vain"), but had come to have the strong narcissistic undertones by the fourteenth century which it still retains today.[57] As a result of these semantic changes, vainglory has become a rarely used word in itself and is now commonly interpreted as referring to vanity (in its modern narcissistic sense).[citation needed]

Christian seven virtues

With Christianity, historic Christian denominations, such as the Catholic Church and Protestant churches,[58] including the Lutheran Church,[59] recognize seven virtues, which correspond inversely to each of the seven deadly sins.

| Vice | Latin | Italian | Virtue | Latin | Italian |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lust | Luxuria | Lussuria | Chastity | Castitas | Castità |

| Gluttony | Gula | Gola | Temperance | Moderatio | Temperanza |

| Greed | Avaritia | Avarizia | Charity (or, sometimes, Generosity) | Caritas (Liberalitas) | Generosità |

| Sloth | Acedia | Accidia | Diligence | Industria | Diligenza |

| Wrath | Ira | Ira | Patience | Patientia | Pazienza |

| Envy | Invidia | Invidia | Gratitude (or Kindness) | Gratia (Humanitas) | Gratitudine |

| Pride | Superbia | Superbia | Humility | Humilitas | Umiltà |

Confession patterns

Confession is the act of admitting the commission of a deadly sin to a priest who, in turn, will forgive the person in the name (in the person) of Christ, give a penance to make up for the sin's offence (partially), and advise the person on what he or she should do afterwards.[tone]

According to a 2009 study by the Jesuit scholar Fr. Roberto Busa, the most common deadly sin confessed by men is lust and the most common deadly sin confessed by women is pride.[60] It was unclear whether these differences were due to the actual number of transgressions committed by each sex or whether differing views on what "counts" or should be confessed caused the observed pattern.[61]

In art

Dante's Purgatorio

The second book of Dante's epic poem The Divine Comedy is structured around the seven deadly sins. The most serious sins are found at the lowest level and are the irrational sins linked to the intelligent aspect, such as pride and envy. Abusing one's passions with wrath or a lack of passion as with sloth also weighs down the soul but not as much as the abuse of one's rational faculty. Abusing one's desires to have one's physical wants met via greed, gluttony, or lust abuses a faculty that humans share with animals. This is still an abuse that weighs down the soul, but it does not weigh it down like other abuses. Thus, the top levels of the Mountain of Purgatory have the top listed sins, while the lowest levels have the more serious sins of wrath, envy and pride.[40]

- luxuria / Lust[62][63][64]

- gula / Gluttony

- avaritia / Greed

- acedia / Sloth

- ira / Wrath

- invidia / Envy

- superbia / Pride

Geoffrey Chaucer's "The Parson's Tale"

The last tale of Chaucer's Canterbury Tales "The Parson's Tale" is not a tale but a sermon that the parson gives against the seven deadly sins. This sermon brings together many common ideas and images about the seven deadly sins. The tale and Dante's work both show how the seven deadly sins were used for confessional purposes or as a way to identify, repent of, and find forgiveness for one's sins.[65][66]

Pieter Bruegel the Elder's Prints of the Seven Deadly Sins

The Dutch artist Pieter Bruegel the Elder created a series of prints showing each of the seven deadly sins. Each print features a central, labeled image that represents the sin. Around the figure are images that show the distortions, degenerations, and destructions caused by the sin.[67] Many of these images come from contemporary Dutch aphorisms.[68]

Edmund Spenser's The Faerie Queene

Spenser's The Faerie Queene was meant to educate young people to embrace virtue and avoid vice, yet it includes a colourful depiction of the House of Pride. Lucifera, the lady of the house, is accompanied by advisers who represent the other seven deadly sins.[citation needed]

William Langland's Piers Plowman

The seven sins are personified and they give a confession to the personification of Repentance in William Langland's Piers Plowman. Only pride is represented by a woman, while the others all represented by male characters.

The Seven Deadly Sins

Kurt Weill and Bertolt Brecht's The Seven Deadly Sins satirized capitalism and its painful abuses as its central character, the victim of a split personality, travels to seven different cities in search of money for her family. In each city, she encounters one of the seven deadly sins, but those sins ironically reverse one's expectations. When the character goes to Los Angeles, for example, she is outraged by injustice, but is told that wrath against capitalism is a sin that she must avoid.[citation needed]

Paul Cadmus' The Seven Deadly Sins

Between 1945 and 1949, the American painter Paul Cadmus created a series of vivid, powerful, and gruesome paintings of each of the seven deadly sins.[69]

Revalorization

Ferdinand Mount maintains that liquid currentness, especially through tabloids, has surprisingly given valor to vices, causing society to regress into that of primitive pagans: "covetousness has been rebranded as retail therapy, sloth is downtime, lust is exploring your sexuality, anger is opening up your feelings, vanity is looking good because you're worth it and gluttony is the religion of foodies".[70]

No comments:

Post a Comment