Do we gallant the love to gist or is the back of such a speak to hug,

is great found a fathom of whom is Odin on the galaxy at a hear,

tried and due is weather of the ice to say hello old friend,

I grasp a big hug to the Milky Way knew!!

Oh fallow grave is the comb of the stream lights?,

is the Moon on the ankle of belief,

does the cheese meat by a meal on the boots,

meow is the cat on the eel.

Wow!

Heave my grate to chapel and say Prey,

my goodness grace,

where is the back of spine on that leaf?,

it is the big each!!

In that is the inch but a bastard does the fell be Well?,

yes.

Heave the earth to ground this Week,

the Spacecraft is but a right on the left of a Hill,

look to the grounded and bank that light on the Switch,

a beth,

then on that is the grave to climb in a tooth,

gear is a head and the hand is the write,

patent to the Custard?,

no,

this is the inscription of an ear and that is the singing verse!

Frank is in good shape however in that Friar is now a tough,

and that is this Earth on sorting Equator's as the Pole is too?,

nigh this hour of the minute clocking an as tech in an ink can.

Funny speak as even the words capture attention as my eyes gaze to the spelling of letter to Holmes method of what is that in the diction:

*An Apology for the Bible, etc - Page 88 - Google Books Result

https://books.google.com/books?id=JehUAAAAcAAJ

Richard Watson - 1796

This srophecy was spokeir in the year before Christ 7133 and, above an hundred' yearsafterwards it was accomplithedywhen - 'Ncbuchadnezzar tookjerusalem, and carried out thence ' all the trcasures of the house of the Lord, and the treasures of the king's house, (2 Kings xxiv. 13.) and when he eonunanded the matter of ...

*Google search as asked: "7133 Before Christ"

☝ About 8,010 results (0.65 seconds)

👇Deism | religious philosophy | Britannica.com

https://www.britannica.com/topic/Deism

Nov 1, 2017 - Deism took deep root in 18th-century Germany after it had ceased to be a vital subject of controversy in England. ... Denis Diderot, in France, translated into French the works of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd earl of Shaftesbury, one of the important English Deists, he often rendered “Deism” as théisme.

☝ About 52,900 results (0.60 seconds)

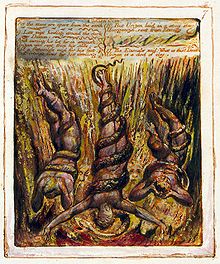

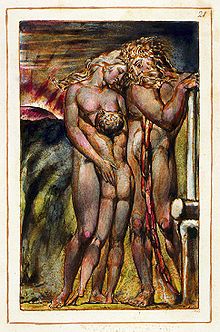

"Book of Urizen Copy G Plate 26" as titled at Google search

🖼About 35,100 results (0.78 seconds)

An Apology for the Bible; in a series of letters addressed to Thomas Paine ...

By Richard Watson

Richard Watson (bishop of Llandaff)

Richard Watson (1737–1816) was an Anglican bishop and academic, who served as the Bishop of Llandaff from 1782 to 1816. He wrote some notable political pamphlets. In theology, he belonged to an influential group of followers of Edmund Law that included also John Hey and William Paley.[1]

Contents

[hide]Life[edit]

Watson was born in Heversham, Westmorland (now Cumbria), and educated at Heversham Grammar School and Trinity College, Cambridge,[2] on a scholarship endowed by Edward Wilson of Nether Levens (1557–1653).[3] In 1759 he graduated as Second Wrangler after having challenged Massey for the position of Senior Wrangler. This challenge, in part, prompted the University Proctor, William Farish, to introduce the practice of assigning specific marks to individual questions in University tests and, in so doing, replaced the practice of 'judgement' at Cambridge with 'marking'. Marking subsequently emerged as the predominant method to determine rank order in meritocratic systems.[4] In 1760 he became a fellow of Trinity[2] and in 1762 received his MA degree. He became a professor of chemistry in 1764 and was elected a fellow of the Royal Societyin 1769 after publishing a paper on the solution of salts in Philosophical Transactions.

Watson's theological career began when he became the Cambridge Regius Professor of Divinity in 1771.[2] In 1773, he married Dorothy Wilson, daughter of Edward Wilson of Dallam Tower and a descendant of the eponymous benefactor who had endowed Watson's scholarship. In 1774, he took up the position of prebendary of Ely Cathedral. He became archdeacon of Ely and rector of Northwold in 1779, leaving the Northwold post two years later to become rector of Knaptoft. In 1782, he left all his previous appointments to take up the post of Bishop of Llandaff, which he held until his death in 1816. In 1788, he purchased the Calgarth estate in Troutbeck Bridge, Windermere, Westmorland. The same year he was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[5]

Watson was buried at St Martin's Church in Windermere.

Works[edit]

Watson contributed to the Revolution controversy, with A treatise upon the authenticity of the Scriptures, and the truth of the Christian religion (1792) and most notably in 1796 when he delivered his counterblast to Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason in An Apology for the Bible which he had "reason to believe, was of singular service in stopping that torrent of irreligion which had been excited by [Paine's] writings".[6] In 1798 he published An Address to the People of Great Britain, which argued for national taxes to be raised to pay for the war against France and to reduce the national debt. Gilbert Wakefield, a Unitarian minister who taught at Warrington Academy, responded with A Reply to Some Parts of the Bishop Llandaff's Address to the People of Great Britain, attacking the privileged position of the wealthy.

An autobiography, Anecdotes of the life of Richard Watson, Bishop of Landaff, was finished in 1814 and published posthumously in 1817.

In the 19th century, it was rumoured that Watson had been the first to propose the electric telegraph, but this is incorrect. At the time William Watson (1715–1787) made researches in electricity, but even he was not involved in the telegraph.[7]

Deism

RELIGIOUS PHILOSOPHY

WRITTEN BY:

Deism, an unorthodox religious attitude that found expression among a group of English writers beginning with Edward Herbert (later 1st Baron Herbert of Cherbury) in the first half of the 17th century and ending with Henry St. John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke, in the middle of the 18th century. These writers subsequently inspired a similar religious attitude in Europe during the second half of the 18th century and in the colonial United States of America in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. In general, Deism refers to what can be called natural religion, the acceptance of a certain body of religious knowledge that is inborn in every person or that can be acquired by the use of reasonand the rejection of religious knowledge when it is acquired through either revelation or the teaching of any church.

Nature And Scope

Though an initial use of the term occurred in 16th-century France, the later appearance of the doctrine on the Continent was stimulated by the translation and adaptation of the English models. The high point of Deist thought occurred in England from about 1689 through 1742, during a period when, despite widespread counterattacks from the established Church of England, there was relative freedom of religious expression following upon the Glorious Revolution that ended the rule of James II and brought William III and Mary II to the throne. Deism took deep root in 18th-century Germany after it had ceased to be a vital subject of controversy in England.

In the 19th and early 20th centuries, the word Deism was used by some theologians in contradistinction to theism, the belief in an immanent God who actively intervenes in the affairs of men. In this sense, Deism was represented as the view of those who reduced the role of God to a mere act of creation in accordance with rational laws discoverable by man and held that, after the original act, God virtually withdrew and refrained from interfering in the processes of nature and the ways of man. So stark an interpretation of the relations of God and man, however, was accepted by very few Deists during the flowering of the doctrine, though their religious antagonists often attempted to force them into this difficult position. Historically, a distinction between theism and Deism has never had wide currency in European thought. As an example, when encyclopaedist Denis Diderot, in France, translated into French the works of Anthony Ashley Cooper, 3rd earl of Shaftesbury, one of the important English Deists, he often rendered “Deism” as théisme.

The Historical Deists

The English Deists

In 1754–56, when the Deist controversy had passed its peak, John Leland, an opponent, wrote a historical and critical compendium of Deist thought, A View of the Principal Deistical Writers that Have Appeared in England in the Last and Present Century; with Observations upon Them, and Some Account of the Answers that Have Been Published Against Them. This work, which began with Lord Herbert of Cherbury and moved through the political philosopher Thomas Hobbes, Charles Blount, the earl of Shaftesbury (Cooper), Anthony Collins, Thomas Woolston, Matthew Tindal, Thomas Morgan, Thomas Chubb, and Viscount Bolingbroke, fixed the canon of who should be included among the Deist writers. In subsequent works, Hobbes usually has been dropped from the list and John Toland included, though he was closer to pantheism than most of the other Deists were. Herbert was not known as a Deist in his day, but Blount and the rest who figured in Leland’s book would have accepted the term Deist as an appropriate designation for their religious position. Simultaneously, it became an adjective of opprobrium in the vocabulary of their opponents. Bishop Edward Stillingfleet’s Letter to a Deist (1677) is an early example of the orthodox use of the epithet.

In Lord Herbert’s treatises five religious ideas were recognized as God-given and innate in the mind of man from the beginning of time: the belief in a supreme being, in the need for his worship, in the pursuit of a pious and virtuous life as the most desirable form of worship, in the need of repentance for sins, and in rewards and punishments in the next world. These fundamental religious beliefs, Herbert held, had been the possession of the first man, and they were basic to all the worthy positive institutionalized religions of later times. Thus, differences among sects and cults all over the world were usually benign, mere modifications of universally accepted truths; they were corruptions only when they led to barbarous practices such as the immolation of human victims and the slaughter of religious rivals.

In England at the turn of the 17th century this general religious attitude assumed a more militant form, particularly in the works of Toland, Shaftesbury, Tindal, Woolston, and Collins. Though the Deists differed among themselves and there is no single work that can be designated as the quintessential expression of Deism, they joined in attacking both the existing orthodox church establishment and the wild manifestations of the dissenters. The tone of these writers was often earthy and pungent, but their Deist ideal was sober natural religion without the trappings of Roman Catholicism and the High Church in England and free from the passionate excesses of Protestant fanatics. In Toland there is great emphasis on the rational element in natural religion; in Shaftesbury more worth is ascribed to the emotive quality of religious experience when it is directed into salutary channels. All are agreed in denouncing every kind of religious intolerance because the core of the various religions is identical. In general, there is a negative evaluation of religious institutions and the priestly corps who direct them. Simple primitive monotheism was practiced by early men without temples, churches, and synagogues, and modern men could readily dispense with religious pomp and ceremony. The more elaborate and exclusive the religious establishment, the more it came under attack. A substantial portion of Deist literature was devoted to the description of the noxious practices of all religions in all times, and the similarities of pagan and Roman Catholic rites were emphasized.

The Deists who presented purely rationalist proofs for the existence of God, usually variations on the argument from the design or order of the universe, were able to derive support from the vision of the lawful physical world that Sir Isaac Newton had delineated. Indeed, in the 18th century, there was a tendency to convert Newton into a matter-of-fact Deist—a transmutation that was contrary to the spirit of both his philosophical and his theological writings.

When Deists were faced with the problem of how man had lapsed from the pure principles of his first forebears into the multiplicity of religious superstitions and crimes committed in the name of God, they ventured a number of conjectures. They surmised that men had fallen into error because of the inherent weakness of human nature; or they subscribed to the idea that a conspiracy of priests had intentionally deceived men with a “rout of ceremonials” in order to maintain power over them.

The role of Christianity in the universal history of religion became problematic. For many religious Deists the teachings of Jesus Christwere not essentially novel but were, in reality, as old as creation, a republication of primitive monotheism. Religious leaders had arisen among many peoples—Socrates, Buddha, Muhammad—and their mission had been to effect a restoration of the simple religious faith of early men. Some writers, while admitting the similarity of Jesus’ message to that of other religious teachers, tended to preserve the unique position of Christianity as a divine revelation. It was possible to believe even in prophetic revelation and still remain a Deist, for revelation could be considered as a natural historical occurrence consonant with the definition of the goodness of God. The more extreme Deists, of course, could not countenance this degree of divine intervention in the affairs of men.

Natural religion was sufficient and certain; the tenets of all positive religions contained extraneous, even impure elements. Deists accepted the moral teachings of the Bible without any commitment to the historical reality of the reports of miracles. Most Deist argumentation attacking the literal interpretation of Scripture as divine revelation leaned upon the findings of 17th-century biblical criticism. Woolston, who resorted to an allegorical interpretation of the whole of the New Testament, was an extremist even among the more audacious Deists. Tindal was perhaps the most moderate of the group. Toland was violent; his denial of all mystery in religion was supported by analogies among Christian, Judaic, and pagan esoteric religious practices, equally condemned as the machinations of priests.

The Deists were particularly vehement against any manifestation of religious fanaticism and enthusiasm. In this respect Shaftesbury’s Letter Concerning Enthusiasm (1708) was probably the crucial document in propagating their ideas. Revolted by the Puritan fanatics of the previous century and by the wild hysteria of a group of French exiles prophesying in London in 1707, Shaftesbury denounced all forms of religious extravagance as perversions of “true” religion. These false prophets were directing religious emotions, benign in themselves, into the wrong channels. Any description of God that depicted his impending vengeance, vindictiveness, jealousy, and destructive cruelty was blasphemous. Because sound religion could find expression only among healthy men, the argument was common in Deist literature that the preaching of extreme asceticism, the practice of self-torture, and the violence of religious persecutions were all evidence of psychological illness and had nothing to do with authentic religious sentiment and conduct. The Deist God, ever gentle, loving, and benevolent, intended men to behave toward one another in the same kindly and tolerant fashion.

Deists in other countries

Ideas of this general character were voiced on the Continent at about the same period by such men as Pierre Bayle, a French philosopherfamous for his encyclopaedic dictionary, even though he would have rejected the Deist identification. During the heyday of the French Philosophes in the 18th century, the more daring thinkers—Voltaire among them—gloried in the name Deist and declared the kinship of their ideas with those of Rationalist English ecclesiastics, such as Samuel Clarke, who would have repudiated the relationship. The dividing line between Deism and atheism among the Philosophes was often rather blurred, as is evidenced by Le Rêve de d’Alembert(written 1769; “The Dream of d’Alembert”), which describes a discussion between the two “fathers” of the Encyclopédie: the Deist Jean Le Rond d’Alembert and the atheist Diderot. Diderot had drawn his inspiration from Shaftesbury, and thus in his early career he was committed to a more emotional Deism. Later in life, however, he shifted to the atheist materialist circle of the baron d’Holbach. When Holbach paraphrased or translated the English Deists, his purpose was frankly atheist; he emphasized those portions of their works that attacked existing religious practices and institutions, neglecting their devotion to natural religion and their adoration of Christ. The Catholic church in 18th-century France did not recognize fine distinctions among heretics, and Deist and atheist works were burned in the same bonfires.

English Deism was transmitted to Germany primarily through translations of Shaftesbury, whose influence upon thought was paramount. In a commentary on Shaftesbury published in 1720, Gottfried Wilhelm Leibniz, a Rationalist philosopher and mathematician, accepted the Deist conception of God as an intelligent Creator but refused the contention that a god who metes out punishments is evil. A sampling of other Deist writers was available particularly through the German rendering of Leland’s work in 1755 and 1756. H.S. Reimarus, author of many philosophical works, maintained in his Apologie oder Schutzschrift für die vernünftigen Verehrer Gottes (“Defense for the Rational Adorers of God”) that the human mind by itself without revelation was capable of reaching a perfect religion.

Reimarus did not dare to publish the book during his lifetime, but it was published in 1774–78 by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, one of the great seminal minds in German literature. According to Lessing, common man, uninstructed and unreflecting, will not reach a perfect knowledge of natural religion; he will forget or ignore it. Thus, the several positive religions can help men achieve more complete awareness of the perfect religion than could ever be attained by any individual mind. Lessing’s Nathan der Weise (1779; “Nathan the Sage”) was noteworthy for the introduction of the Deist spirit of religion into the drama; in the famous parable of the three rings, the major monotheistic religions were presented as equally true in the eyes of God.

Although Lessing’s rational Deism was the object of violent attack on the part of Pietist writers and more mystical thinkers, it influenced such men as Moses Mendelssohn, a German Jewish philosopher who applied Deism to the Jewish faith. Immanuel Kant, the most important figure in 18th-century German philosophy, stressed the moral element in natural religion when he wrote that moral principles are not the result of any revelation but rather originate from the very structure of man’s reason. English Deists, however, continued to influence German Deism. Witnesses attest that virtually the whole officer corps of Frederick the Great was “infected” with Deism and that Collins and Tindal were favourite reading in the army.

By the end of the 18th century, Deism had become a dominant religious attitude among intellectual and upper-class Americans. Benjamin Franklin, the great sage of the colonies and then of the new republic, summarized in a letter to Ezra Stiles, president of Yale College, a personal creed that almost literally reproduced Herbert’s five fundamental beliefs. The second and third presidents of the United States also held Deistic convictions, as is amply evidenced in their correspondence. “The ten commandments and the sermon on the mount contain my religion,” John Adams wrote to Thomas Jefferson in 1816.

Influence Of Deism Since The Early 20th Century

Certain philosophical and religious movements starting in the 20th century have been characterized as Deist in nature, mainly in the United States. For example, many Unitarian Universalist congregations have Deist members and even Deist discussion groups and fellowships. Further, such modern variants as “pandeism,” which attempted to unite aspects of Deism with pantheism, held that through the act of creation God became the universe. There is thus no theological need to posit any special relationship between God and creation; rather, God is the universe and not a transcendent entity that created and subsequently governs it. The American logician and process philosopher Charles Hartshorne considered Deism, pandeism, and pantheism as reasonable doctrines of the nature of God; however, he rejected all of these in favour of panentheism, the belief that God is present in the universe while being greater than it. The English philosopher Anthony Flew also stirred controversy when he publicly abandoned his personal conviction in atheism in favour of what he called a “weak” form of Deism that asserted God’s existence yet eschewed positions on such traditional theological matters as God’s relationship with the world or revelation.

Deism

This article contains too many or too-lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (September 2015)

Part of a series on God

Deism (/ˈdiː.ɪzəm/ DEE-iz-əm [1][2] or /ˈdeɪ.ɪzəm/ DAY-iz-əm; derived from Latin "deus" meaning "god") is a philosophical position that posits that God (or in some cases, gods) does not interfere directly with the world; conversely it can also be stated as a system of belief which posits God's existence as the cause of all things, and admits His perfection (and usually the existence of natural law and Providence) but rejects Divine revelation or direct intervention of God in the universe by miracles. It also rejects revelation as a source of religious knowledge and asserts that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator or absolute principle of the universe.[3][4][5]

Deism gained prominence among intellectuals during the Age of Enlightenment, especially in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. Typically, these had been raised as Christians and believed in one God, but they had become disenchanted with organized religion and orthodox teachings such as the Trinity, Biblical inerrancy, and the supernaturalinterpretation of events, such as miracles.[6] Included in those influenced by its ideas were leaders of the American and French Revolutions.[7]

Today, deism is considered to exist in the classical and modern forms,[8] where the classical view takes what is called a "cold" approach by asserting the non-intervention of deity in the natural behavior of the created universe, while the modern deist formulation can be either "warm" (citing an involved deity) or "cold" (citing an uninvolved deity). These lead to many subdivisions of modern deism, which tends, therefore, to serve as an overall category of belief.[9]

This article contains too many or too-lengthy quotations for an encyclopedic entry. (September 2015)

|

| Part of a series on |

| God |

|---|

Deism (/ˈdiː.ɪzəm/ DEE-iz-əm [1][2] or /ˈdeɪ.ɪzəm/ DAY-iz-əm; derived from Latin "deus" meaning "god") is a philosophical position that posits that God (or in some cases, gods) does not interfere directly with the world; conversely it can also be stated as a system of belief which posits God's existence as the cause of all things, and admits His perfection (and usually the existence of natural law and Providence) but rejects Divine revelation or direct intervention of God in the universe by miracles. It also rejects revelation as a source of religious knowledge and asserts that reason and observation of the natural world are sufficient to determine the existence of a single creator or absolute principle of the universe.[3][4][5]

Deism gained prominence among intellectuals during the Age of Enlightenment, especially in Britain, France, Germany, and the United States. Typically, these had been raised as Christians and believed in one God, but they had become disenchanted with organized religion and orthodox teachings such as the Trinity, Biblical inerrancy, and the supernaturalinterpretation of events, such as miracles.[6] Included in those influenced by its ideas were leaders of the American and French Revolutions.[7]

Today, deism is considered to exist in the classical and modern forms,[8] where the classical view takes what is called a "cold" approach by asserting the non-intervention of deity in the natural behavior of the created universe, while the modern deist formulation can be either "warm" (citing an involved deity) or "cold" (citing an uninvolved deity). These lead to many subdivisions of modern deism, which tends, therefore, to serve as an overall category of belief.[9]

Contents

Overview[edit]

Deism is a theological theory concerning the relationship between a Creator and the natural world. Deistic viewpoints emerged during the scientific revolution of 17th-century Europe and came to exert a powerful influence during the 18th century Enlightenment. Deism stood between the narrow dogmatism of the period and skepticism. Though deists rejected atheism,[10] they often were called "atheists" by more traditional theists.[11] There were a number of different forms in the 17th and 18th centuries. In England, deists included a range of people from anti-Christian to non-Christian theists.[12]

For deists, human beings can know God only via reason and the observation of nature, but not by revelation or by supernatural manifestations (such as miracles) – phenomena which deists regard with caution if not skepticism. Deism is related to naturalism because it credits the formation of life and the universe to a higher power, using only natural processes. Deism may also include a spiritual element, involving experiences of God and nature.[13]

The words deism and theism both derive from words for "god": the former from Latin deus, the latter from Greek theós (θεός).

Perhaps the first recorded use of the term deist (French: déiste) occurs in Pierre Viret's Instruction Chrétienne en la doctrine de la foi et de l'Évangile (Christian teaching on the doctrine of faith and the Gospel, 1564), reprinted in Bayle's Dictionnaire (1697) entry Viret. Viret, a Calvinist, flagged the term as a neologism (un mot tout nouveau),[15] and regarded deism as a new form of Italian heresy.[16] Viret wrote that a group of people believed in "some sort of God" like the Jews and Turks but regarded the doctrine of the evangelists and the apostles as a mere myth.[citation needed] According to him Deists wrongly misinterpreted the liberty given to them during the reform period.

Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648) is generally considered[by whom?] the "father of English Deism", and his book De Veritate (1624) the first major statement of deism. Deism flourished in England between 1690 and 1740, at which time Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), also called "The Deist's Bible", gained much attention. Later deism spread to France (notably through the work of Voltaire), to Germany, and to North America.

Deism is a theological theory concerning the relationship between a Creator and the natural world. Deistic viewpoints emerged during the scientific revolution of 17th-century Europe and came to exert a powerful influence during the 18th century Enlightenment. Deism stood between the narrow dogmatism of the period and skepticism. Though deists rejected atheism,[10] they often were called "atheists" by more traditional theists.[11] There were a number of different forms in the 17th and 18th centuries. In England, deists included a range of people from anti-Christian to non-Christian theists.[12]

For deists, human beings can know God only via reason and the observation of nature, but not by revelation or by supernatural manifestations (such as miracles) – phenomena which deists regard with caution if not skepticism. Deism is related to naturalism because it credits the formation of life and the universe to a higher power, using only natural processes. Deism may also include a spiritual element, involving experiences of God and nature.[13]

The words deism and theism both derive from words for "god": the former from Latin deus, the latter from Greek theós (θεός).

Perhaps the first recorded use of the term deist (French: déiste) occurs in Pierre Viret's Instruction Chrétienne en la doctrine de la foi et de l'Évangile (Christian teaching on the doctrine of faith and the Gospel, 1564), reprinted in Bayle's Dictionnaire (1697) entry Viret. Viret, a Calvinist, flagged the term as a neologism (un mot tout nouveau),[15] and regarded deism as a new form of Italian heresy.[16] Viret wrote that a group of people believed in "some sort of God" like the Jews and Turks but regarded the doctrine of the evangelists and the apostles as a mere myth.[citation needed] According to him Deists wrongly misinterpreted the liberty given to them during the reform period.

Lord Herbert of Cherbury (1583–1648) is generally considered[by whom?] the "father of English Deism", and his book De Veritate (1624) the first major statement of deism. Deism flourished in England between 1690 and 1740, at which time Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), also called "The Deist's Bible", gained much attention. Later deism spread to France (notably through the work of Voltaire), to Germany, and to North America.

Features[edit]

The concept of deism covers a wide variety of positions on a wide variety of religious issues. Sir Leslie Stephen's English Thought in the Eighteenth Centurydescribes the core of deism as consisting of "critical" and "constructional" elements.[citation needed]

Critical elements of deist thought included:

- Rejection of religions that are based on books that claim to contain the revealed word of God.

- Rejection of religious dogma and demagogy.

- Skepticism of reports of miracles, prophecies and religious "mysteries".

Constructional elements of deist thought included:

- God exists and created the universe.

- God gave humans the ability to reason.

Individual deists varied in the critical and constructive elements they argued for. Some rejected miracles and prophecies, but still considered themselves Christians because they believed in what they felt was the pure, original form of Christianity – that is, Christianity as it supposedly existed before it was corrupted by additions of such superstitions as miracles, prophecies, and the doctrine of the Trinity. Some deists rejected the claim of Jesus' divinity but continued to hold him in high regard as a moral teacher, a position known as Christian deism, exemplified by Thomas Jefferson's famous Jefferson Bible and Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation. Other, more radical deists rejected Christianity altogether and expressed hostility toward Christianity, which they regarded as pure superstition. In return, Christian writers often charged radical deists with atheism.

Note that the terms constructive and critical are used to refer to aspects of deistic thought, not sects or subtypes of deism – it would be incorrect to classify any particular deist author as "a constructive deist" or "a critical deist". As Peter Gay notes:

It should be noted, however, that the constructive element of deism was not unique to deism. It was the same as the natural theology that was so prevalent in all English theology in the 17th and 18th centuries. What set deists apart from their more orthodox contemporaries were their critical concerns.

One of the remarkable features of deism is that the critical elements did not overpower the constructive elements. As E. Graham Waring observed,[17] "A strange feature of the [Deist] controversy is the apparent acceptance of all parties of the conviction of the existence of God." And Basil Willey observed:[18]

The concept of deism covers a wide variety of positions on a wide variety of religious issues. Sir Leslie Stephen's English Thought in the Eighteenth Centurydescribes the core of deism as consisting of "critical" and "constructional" elements.[citation needed]

Critical elements of deist thought included:

- Rejection of religions that are based on books that claim to contain the revealed word of God.

- Rejection of religious dogma and demagogy.

- Skepticism of reports of miracles, prophecies and religious "mysteries".

Constructional elements of deist thought included:

- God exists and created the universe.

- God gave humans the ability to reason.

Individual deists varied in the critical and constructive elements they argued for. Some rejected miracles and prophecies, but still considered themselves Christians because they believed in what they felt was the pure, original form of Christianity – that is, Christianity as it supposedly existed before it was corrupted by additions of such superstitions as miracles, prophecies, and the doctrine of the Trinity. Some deists rejected the claim of Jesus' divinity but continued to hold him in high regard as a moral teacher, a position known as Christian deism, exemplified by Thomas Jefferson's famous Jefferson Bible and Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation. Other, more radical deists rejected Christianity altogether and expressed hostility toward Christianity, which they regarded as pure superstition. In return, Christian writers often charged radical deists with atheism.

Note that the terms constructive and critical are used to refer to aspects of deistic thought, not sects or subtypes of deism – it would be incorrect to classify any particular deist author as "a constructive deist" or "a critical deist". As Peter Gay notes:

It should be noted, however, that the constructive element of deism was not unique to deism. It was the same as the natural theology that was so prevalent in all English theology in the 17th and 18th centuries. What set deists apart from their more orthodox contemporaries were their critical concerns.

One of the remarkable features of deism is that the critical elements did not overpower the constructive elements. As E. Graham Waring observed,[17] "A strange feature of the [Deist] controversy is the apparent acceptance of all parties of the conviction of the existence of God." And Basil Willey observed:[18]

Concepts of "reason"[edit]

According to the deists, our reason gives us all the information we need:

Consequently, the deists attempted to use reason as a critical tool for exposing and rejecting what they saw as nonsense:

According to the deists, our reason gives us all the information we need:

Consequently, the deists attempted to use reason as a critical tool for exposing and rejecting what they saw as nonsense:

Arguments for the existence of God[edit]

Some deists used the cosmological argument for the existence of God - as did Thomas Hobbes in several of his writings:

Some deists used the cosmological argument for the existence of God - as did Thomas Hobbes in several of his writings:

History of religion and the deist mission[edit]

Most deists (see for instance Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation and Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason) saw the religions of their day as corruptions of an original, pure religion that was simple and rational. They felt that this original pure religion had become corrupted by "priests" who had manipulated it for personal gain and for the class interests of the priesthood in general.[21]

According to this world view, over time "priests" had succeeded in encrusting the original simple, rational religion with all kinds of superstitions and "mysteries" – irrational theological doctrines. Laymen were told by the priests that only the priests really knew what was necessary for salvation and that laymen must accept the "mysteries" on faith and on the priests' authority. This kept the laity baffled by the nonsensical "mysteries", confused, and dependent on the priests for information about the requirements for salvation. The priests consequently enjoyed a position of considerable power over the laity, which they strove to maintain and increase. Deists referred to this kind of manipulation of religious doctrine as "priestcraft", a highly derogatory term. As Thomas Paine wrote:

Deists saw their mission as the stripping away of "priestcraft" and "mysteries" from religion, thereby restoring religion to its original, true condition – simple and rational. In many cases, they considered true, original Christianity to be the same as this original natural religion. As Matthew Tindal put it:

One implication of this deist creation myth was that primitive societies, or societies that existed in the distant past, should have religious beliefs that are less encrusted with superstitions and closer to those of natural theology. This position gradually became less plausible as thinkers such as David Hume began studying the natural history of religion and suggesting that the origins of religion lay not in reason but in the emotions, specifically the fear of the unknown.

Most deists (see for instance Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation and Thomas Paine's The Age of Reason) saw the religions of their day as corruptions of an original, pure religion that was simple and rational. They felt that this original pure religion had become corrupted by "priests" who had manipulated it for personal gain and for the class interests of the priesthood in general.[21]

According to this world view, over time "priests" had succeeded in encrusting the original simple, rational religion with all kinds of superstitions and "mysteries" – irrational theological doctrines. Laymen were told by the priests that only the priests really knew what was necessary for salvation and that laymen must accept the "mysteries" on faith and on the priests' authority. This kept the laity baffled by the nonsensical "mysteries", confused, and dependent on the priests for information about the requirements for salvation. The priests consequently enjoyed a position of considerable power over the laity, which they strove to maintain and increase. Deists referred to this kind of manipulation of religious doctrine as "priestcraft", a highly derogatory term. As Thomas Paine wrote:

Deists saw their mission as the stripping away of "priestcraft" and "mysteries" from religion, thereby restoring religion to its original, true condition – simple and rational. In many cases, they considered true, original Christianity to be the same as this original natural religion. As Matthew Tindal put it:

One implication of this deist creation myth was that primitive societies, or societies that existed in the distant past, should have religious beliefs that are less encrusted with superstitions and closer to those of natural theology. This position gradually became less plausible as thinkers such as David Hume began studying the natural history of religion and suggesting that the origins of religion lay not in reason but in the emotions, specifically the fear of the unknown.

Freedom and necessity[edit]

Enlightenment thinkers, under the influence of Newtonian science, tended to view the universe as a vast machine, created and set in motion by a creator being, that continues to operate according to natural law, without any divine intervention. This view naturally led to what was then usually called necessitarianism[23] (the modern term is determinism): the view that everything in the universe – including human behavior – is completely causally determined by antecedent circumstances and natural law. (See, for example, La Mettrie's L'Homme machine.) As a consequence, debates about freedom versus "necessity" were a regular feature of Enlightenment religious and philosophical discussions.

Because of their high regard for natural law and for the idea of a universe without miracles, deists were especially susceptible to the temptations of determinism. Reflecting the intellectual climate of the time, there were differences among deists about freedom and determinism. Some, such as Anthony Collins, actually were necessitarians.[24]

Enlightenment thinkers, under the influence of Newtonian science, tended to view the universe as a vast machine, created and set in motion by a creator being, that continues to operate according to natural law, without any divine intervention. This view naturally led to what was then usually called necessitarianism[23] (the modern term is determinism): the view that everything in the universe – including human behavior – is completely causally determined by antecedent circumstances and natural law. (See, for example, La Mettrie's L'Homme machine.) As a consequence, debates about freedom versus "necessity" were a regular feature of Enlightenment religious and philosophical discussions.

Because of their high regard for natural law and for the idea of a universe without miracles, deists were especially susceptible to the temptations of determinism. Reflecting the intellectual climate of the time, there were differences among deists about freedom and determinism. Some, such as Anthony Collins, actually were necessitarians.[24]

Immortality of the soul[edit]

Deists hold a variety of beliefs about the soul. Some, such as Lord Herbert of Cherbury and William Wollaston,[25] held that souls exist, survive death, and in the afterlife are rewarded or punished by God for their behavior in life. Some, such as Benjamin Franklin, believed in reincarnation or resurrection. Others, such as Thomas Paine, had definitive beliefs about the immortality of the soul:

Still others such as Anthony Collins,[26] Bolingbroke, Thomas Chubb, and Peter Annet were materialists and either denied or doubted the immortality of the soul.[27]

Deists hold a variety of beliefs about the soul. Some, such as Lord Herbert of Cherbury and William Wollaston,[25] held that souls exist, survive death, and in the afterlife are rewarded or punished by God for their behavior in life. Some, such as Benjamin Franklin, believed in reincarnation or resurrection. Others, such as Thomas Paine, had definitive beliefs about the immortality of the soul:

Still others such as Anthony Collins,[26] Bolingbroke, Thomas Chubb, and Peter Annet were materialists and either denied or doubted the immortality of the soul.[27]

Terminology[edit]

Deist authors – and 17th- and 18th-century theologians in general – referred to God using a variety of vivid circumlocutions such as:[citation needed]

- Divine Providence

- Supreme Being

- Divine Watchmaker

- Nature's God. Used in the United States Declaration of Independence

- Father of Lights. Benjamin Franklin used this terminology when proposing that meetings of the Constitutional Convention begin with prayers[28]

Deist authors – and 17th- and 18th-century theologians in general – referred to God using a variety of vivid circumlocutions such as:[citation needed]

- Divine Providence

- Supreme Being

- Divine Watchmaker

- Nature's God. Used in the United States Declaration of Independence

- Father of Lights. Benjamin Franklin used this terminology when proposing that meetings of the Constitutional Convention begin with prayers[28]

Classical deism[edit]

Historical background[edit]

Deistic thinking has existed since ancient times. Among the Ancient Greeks, Heraclitus conceived of a logos, a supreme rational principle, and said the wisdom "by which all things are steered through all things" was "both willing and unwilling to be called Zeus (God)." Plato envisaged God as a Demiurge or 'craftsman'. Outside ancient Greece many other cultures have expressed views that resemble deism in some respects. However, the word "deism", as it is understood today, is generally used to refer to the movement toward natural theology or freethinking that occurred in 17th-century Europe, and specifically in Britain.

Natural theology is a facet of the revolution in world view that occurred in Europe in the 17th century. To understand the background to that revolution is also to understand the background of deism. Several cultural movements of the time contributed to the movement.[29]

Deistic thinking has existed since ancient times. Among the Ancient Greeks, Heraclitus conceived of a logos, a supreme rational principle, and said the wisdom "by which all things are steered through all things" was "both willing and unwilling to be called Zeus (God)." Plato envisaged God as a Demiurge or 'craftsman'. Outside ancient Greece many other cultures have expressed views that resemble deism in some respects. However, the word "deism", as it is understood today, is generally used to refer to the movement toward natural theology or freethinking that occurred in 17th-century Europe, and specifically in Britain.

Natural theology is a facet of the revolution in world view that occurred in Europe in the 17th century. To understand the background to that revolution is also to understand the background of deism. Several cultural movements of the time contributed to the movement.[29]

Discovery of diversity[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

The humanist tradition of the Renaissance included a revival of interest in Europe's classical past in ancient Greece and Rome. The veneration of that classical past, particularly pre-Christian Rome, the new availability of Greek philosophical works, the successes of humanism and natural science along with the fragmentation of the Christian churches and increased understanding of other faiths, all helped erode the image of the church as the unique source of wisdom, destined to dominate the whole world.

In addition, study of classical documents led to the realization that some historical documents are less reliable than others, which led to the beginnings of biblical criticism. In particular, when scholars worked on biblical manuscripts, they began developing the principles of textual criticism and a view of the New Testament being the product of a particular historical period different from their own.

In addition to discovering diversity in the past, Europeans discovered diversity in the present. The voyages of discovery of the 16th and 17th centuries acquainted Europeans with new and different cultures in the Americas, in Asia, and in the Pacific. They discovered a greater amount of cultural diversity than they had ever imagined, and the question arose of how this vast amount of human cultural diversity could be compatible with the biblical account of Noah's descendants. In particular, the ideas of Confucius, translated into European languages by Jesuit missionaries like Michele Ruggieri, Philippe Couplet, and François Noël, are thought to have had considerable influence on the deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Christianity.[31][32]

In particular, cultural diversity with respect to religious beliefs could no longer be ignored. As Herbert wrote in De Religione Laici (1645),

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The humanist tradition of the Renaissance included a revival of interest in Europe's classical past in ancient Greece and Rome. The veneration of that classical past, particularly pre-Christian Rome, the new availability of Greek philosophical works, the successes of humanism and natural science along with the fragmentation of the Christian churches and increased understanding of other faiths, all helped erode the image of the church as the unique source of wisdom, destined to dominate the whole world.

In addition, study of classical documents led to the realization that some historical documents are less reliable than others, which led to the beginnings of biblical criticism. In particular, when scholars worked on biblical manuscripts, they began developing the principles of textual criticism and a view of the New Testament being the product of a particular historical period different from their own.

In addition to discovering diversity in the past, Europeans discovered diversity in the present. The voyages of discovery of the 16th and 17th centuries acquainted Europeans with new and different cultures in the Americas, in Asia, and in the Pacific. They discovered a greater amount of cultural diversity than they had ever imagined, and the question arose of how this vast amount of human cultural diversity could be compatible with the biblical account of Noah's descendants. In particular, the ideas of Confucius, translated into European languages by Jesuit missionaries like Michele Ruggieri, Philippe Couplet, and François Noël, are thought to have had considerable influence on the deists and other philosophical groups of the Enlightenment who were interested by the integration of the system of morality of Confucius into Christianity.[31][32]

In particular, cultural diversity with respect to religious beliefs could no longer be ignored. As Herbert wrote in De Religione Laici (1645),

Religious conflict in Europe[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Europe had been plagued by sectarian conflicts and religious wars since the beginning of the Reformation. In 1642, when Lord Herbert of Cherbury's De Veritate was published, the Thirty Years War had been raging on continental Europe for nearly 25 years. It was an enormously destructive war that (it is estimated) destroyed 15–20% of the population of Germany. At the same time, the English Civil War pitting King against Parliament was just beginning.

Such massive violence led to a search for natural religious truths – truths that could be universally accepted, because they had been either "written in the book of Nature" or "engraved on the human mind" by God.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Europe had been plagued by sectarian conflicts and religious wars since the beginning of the Reformation. In 1642, when Lord Herbert of Cherbury's De Veritate was published, the Thirty Years War had been raging on continental Europe for nearly 25 years. It was an enormously destructive war that (it is estimated) destroyed 15–20% of the population of Germany. At the same time, the English Civil War pitting King against Parliament was just beginning.

Such massive violence led to a search for natural religious truths – truths that could be universally accepted, because they had been either "written in the book of Nature" or "engraved on the human mind" by God.

Advances in scientific knowledge[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

The 17th century saw a remarkable advance in scientific knowledge, the scientific revolution. The work of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo set aside the old notion that the earth was the center of the universe. These discoveries posed a serious challenge to biblical and religious authorities, Galileo's condemnation for heresy being an example. In consequence the Bible came to be seen as authoritative on matters of faith and morals but no longer authoritative (or meant to be) on science.

Isaac Newton's (1642–1727) mathematical explanation of universal gravitation explained the behavior both of objects here on earth and of objects in the heavens in a way that promoted a worldview in which the natural universe is controlled by laws of nature. This, in turn, suggested a theology in which God created the universe, set it in motion controlled by natural law and retired from the scene. The new awareness of the explanatory power of universal natural law also produced a growing skepticism about such religious staples as miracles (violations of natural law) and about religious books that reported them.

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

The 17th century saw a remarkable advance in scientific knowledge, the scientific revolution. The work of Copernicus, Kepler, and Galileo set aside the old notion that the earth was the center of the universe. These discoveries posed a serious challenge to biblical and religious authorities, Galileo's condemnation for heresy being an example. In consequence the Bible came to be seen as authoritative on matters of faith and morals but no longer authoritative (or meant to be) on science.

Isaac Newton's (1642–1727) mathematical explanation of universal gravitation explained the behavior both of objects here on earth and of objects in the heavens in a way that promoted a worldview in which the natural universe is controlled by laws of nature. This, in turn, suggested a theology in which God created the universe, set it in motion controlled by natural law and retired from the scene. The new awareness of the explanatory power of universal natural law also produced a growing skepticism about such religious staples as miracles (violations of natural law) and about religious books that reported them.

Precursors[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

Early works of biblical criticism, such as Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and Spinoza's Theologico-Political Treatise, as well as works by lesser-known authors such as Richard Simon and Isaac La Peyrère, paved the way for the development of critical deism.

An important precursor to deism was the work of Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury (d. 1648). He has been called the "father of English deism", and his book De Veritate (On Truth, as It Is Distinguished from Revelation, the Probable, the Possible, and the False) (1624) "the first major statement of deism".[33][34] However, his beliefs in divine intervention, particularly in response to prayer, are at odds with the basic ideas of deism. In Herbert's account of one incident, he prayed "I am not satisfied enough whether I shall publish this Book, De Veritate; if it be for Thy glory, I beseech Thee give me some Sign from Heaven, if not, I shall suppress it" and recounts that the response was "a loud tho' yet gentle Noise came from the Heavens (for it was like nothing on Earth)... I had the Sign I demanded".[35]

Like his contemporary Descartes, Herbert searched for the foundations of knowledge. In fact, the first two thirds of De Veritate are devoted to an exposition of Herbert's theory of knowledge. Herbert distinguished truths obtained through experience, and through reasoning about experience, from innate truths and from revealed truths. Innate truths are imprinted on our minds, and the evidence that they are so imprinted is that they are universally accepted. Herbert's term for universally accepted truths was notitiae communes – common notions.

In the realm of religion, Herbert believed that there were five common notions.[10]

The following lengthy quote from Herbert can give the flavor of his writing and demonstrate the sense of the importance that Herbert attributed to innate Common Notions, which can help in understanding the effect of Locke's attack on innate ideas on Herbert's philosophy:

According to Gay, Herbert had relatively few followers, and it was not until the 1680s that Herbert found a true successor in Charles Blount (1654–1693). Blount made one special contribution to the deist debate: "by utilizing his wide classical learning, Blount demonstrated how to use pagan writers, and pagan ideas, against Christianity. ... Other Deists were to follow his lead."[36]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2012) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

Early works of biblical criticism, such as Thomas Hobbes's Leviathan and Spinoza's Theologico-Political Treatise, as well as works by lesser-known authors such as Richard Simon and Isaac La Peyrère, paved the way for the development of critical deism.

An important precursor to deism was the work of Edward, Lord Herbert of Cherbury (d. 1648). He has been called the "father of English deism", and his book De Veritate (On Truth, as It Is Distinguished from Revelation, the Probable, the Possible, and the False) (1624) "the first major statement of deism".[33][34] However, his beliefs in divine intervention, particularly in response to prayer, are at odds with the basic ideas of deism. In Herbert's account of one incident, he prayed "I am not satisfied enough whether I shall publish this Book, De Veritate; if it be for Thy glory, I beseech Thee give me some Sign from Heaven, if not, I shall suppress it" and recounts that the response was "a loud tho' yet gentle Noise came from the Heavens (for it was like nothing on Earth)... I had the Sign I demanded".[35]

Like his contemporary Descartes, Herbert searched for the foundations of knowledge. In fact, the first two thirds of De Veritate are devoted to an exposition of Herbert's theory of knowledge. Herbert distinguished truths obtained through experience, and through reasoning about experience, from innate truths and from revealed truths. Innate truths are imprinted on our minds, and the evidence that they are so imprinted is that they are universally accepted. Herbert's term for universally accepted truths was notitiae communes – common notions.

In the realm of religion, Herbert believed that there were five common notions.[10]

The following lengthy quote from Herbert can give the flavor of his writing and demonstrate the sense of the importance that Herbert attributed to innate Common Notions, which can help in understanding the effect of Locke's attack on innate ideas on Herbert's philosophy:

According to Gay, Herbert had relatively few followers, and it was not until the 1680s that Herbert found a true successor in Charles Blount (1654–1693). Blount made one special contribution to the deist debate: "by utilizing his wide classical learning, Blount demonstrated how to use pagan writers, and pagan ideas, against Christianity. ... Other Deists were to follow his lead."[36]

Deism in Britain[edit]

John Locke[edit]

The publication of John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689, but dated 1690) marks a major turning point in the history of deism. Since Herbert's De Veritate, innate ideas had been the foundation of deist epistemology. Locke's famous attack on innate ideas in the first book of the Essay effectively destroyed that foundation and replaced it with a theory of knowledge based on experience. Innatist deism was replaced by empiricist deism. Locke himself was not a deist. He believed in both miracles and revelation, and he regarded miracles as the main proof of revelation.[37]

After Locke, constructive deism could no longer appeal to innate ideas for justification of its basic tenets such as the existence of God. Instead, under the influence of Locke and Newton, deists turned to natural theology and to arguments based on experience and nature: the cosmological argument and the argument from design.

The publication of John Locke's An Essay Concerning Human Understanding (1689, but dated 1690) marks a major turning point in the history of deism. Since Herbert's De Veritate, innate ideas had been the foundation of deist epistemology. Locke's famous attack on innate ideas in the first book of the Essay effectively destroyed that foundation and replaced it with a theory of knowledge based on experience. Innatist deism was replaced by empiricist deism. Locke himself was not a deist. He believed in both miracles and revelation, and he regarded miracles as the main proof of revelation.[37]

After Locke, constructive deism could no longer appeal to innate ideas for justification of its basic tenets such as the existence of God. Instead, under the influence of Locke and Newton, deists turned to natural theology and to arguments based on experience and nature: the cosmological argument and the argument from design.

Flowering of classical deism, 1690–1740[edit]

Peter Gay places the zenith of deism "from the end of the 1690s, when the vehement response to John Toland's Christianity not Mysterious (1696) started the deist debate, to the end of the 1740s when the tepid response to Conyers Middleton's Free Inquiry signalled its close."[38]

During this period, prominent British deists included William Wollastson, Charles Blount, and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke.[39]

The influential author Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury is also usually categorized as a deist. Although he did not think of himself as a deist, he shared so many attitudes with deists that Gay calls him "a Deist in fact, if not in name".[40]

Notable late-classical deists include Peter Annet (1693–1769), Thomas Chubb (1679–1747), Thomas Morgan (?–1743), and Conyers Middleton (1683–1750).

Peter Gay places the zenith of deism "from the end of the 1690s, when the vehement response to John Toland's Christianity not Mysterious (1696) started the deist debate, to the end of the 1740s when the tepid response to Conyers Middleton's Free Inquiry signalled its close."[38]

During this period, prominent British deists included William Wollastson, Charles Blount, and Henry St John, 1st Viscount Bolingbroke.[39]

The influential author Anthony Ashley-Cooper, Third Earl of Shaftesbury is also usually categorized as a deist. Although he did not think of himself as a deist, he shared so many attitudes with deists that Gay calls him "a Deist in fact, if not in name".[40]

Notable late-classical deists include Peter Annet (1693–1769), Thomas Chubb (1679–1747), Thomas Morgan (?–1743), and Conyers Middleton (1683–1750).

Matthew Tindal[edit]

Especially noteworthy is Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), which "became, very soon after its publication, the focal center of the deist controversy. Because almost every argument, quotation, and issue raised for decades can be found here, the work is often termed 'the deist's Bible'."[41] Following Locke's successful attack on innate ideas, Tindal's "Deist Bible" redefined the foundation of deist epistemology as knowledge based on experience or human reason. This effectively widened the gap between traditional Christians and what he called "Christian Deists", since this new foundation required that "revealed" truth be validated through human reason.

Especially noteworthy is Matthew Tindal's Christianity as Old as the Creation (1730), which "became, very soon after its publication, the focal center of the deist controversy. Because almost every argument, quotation, and issue raised for decades can be found here, the work is often termed 'the deist's Bible'."[41] Following Locke's successful attack on innate ideas, Tindal's "Deist Bible" redefined the foundation of deist epistemology as knowledge based on experience or human reason. This effectively widened the gap between traditional Christians and what he called "Christian Deists", since this new foundation required that "revealed" truth be validated through human reason.

David Hume[edit]

The writings of David Hume are sometimes credited with causing or contributing to the decline of deism. English deism, however, was already in decline before Hume's works on religion (1757,1779) were published.[42]

Furthermore, some writers maintain that Hume's writings on religion were not very influential at the time that they were published.[43]

Nevertheless, modern scholars find it interesting to study the implications of his thoughts for deism.

- Hume's skepticism about miracles makes him a natural ally of deism.

- His skepticism about the validity of natural religion cuts equally against deism and deism's opponents, who were also deeply involved in natural theology. But his famous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were not published until 1779, by which time deism had almost vanished in England.

In the Natural History of Religion (1757), Hume contends that polytheism, not monotheism, was "the first and most ancient religion of mankind". In addition, contends Hume, the psychological basis of religion is not reason, but fear of the unknown.

As E. Graham Waring saw it;[17]

Experts dispute whether Hume was a deist, an atheist, or something else. Hume himself was uncomfortable with the terms deist and atheist, and Hume scholar Paul Russell has argued that the best and safest term for Hume's views is irreligion.[44]

The writings of David Hume are sometimes credited with causing or contributing to the decline of deism. English deism, however, was already in decline before Hume's works on religion (1757,1779) were published.[42]

Furthermore, some writers maintain that Hume's writings on religion were not very influential at the time that they were published.[43]

Nevertheless, modern scholars find it interesting to study the implications of his thoughts for deism.

- Hume's skepticism about miracles makes him a natural ally of deism.

- His skepticism about the validity of natural religion cuts equally against deism and deism's opponents, who were also deeply involved in natural theology. But his famous Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion were not published until 1779, by which time deism had almost vanished in England.

In the Natural History of Religion (1757), Hume contends that polytheism, not monotheism, was "the first and most ancient religion of mankind". In addition, contends Hume, the psychological basis of religion is not reason, but fear of the unknown.

As E. Graham Waring saw it;[17]

Experts dispute whether Hume was a deist, an atheist, or something else. Hume himself was uncomfortable with the terms deist and atheist, and Hume scholar Paul Russell has argued that the best and safest term for Hume's views is irreligion.[44]

Deism in Continental Europe[edit]

English deism, in the words of Peter Gay, "travelled well. ... As Deism waned in England, it waxed in France and the German states."[45]

France had its own tradition of religious skepticism and natural theology in the works of Montaigne, Bayle, and Montesquieu. The most famous of the French deists was Voltaire, who acquired a taste for Newtonian science, and reinforcement of deistic inclinations, during a two-year visit to England starting in 1726.

French deists also included Maximilien Robespierre and Rousseau. For a short period of time during the French Revolution the Cult of the Supreme Being was the state religion of France.

Kant's identification with deism is controversial. An argument in favor of Kant as deist is Alan Wood's "Kant's Deism," in P. Rossi and M. Wreen (eds.), Kant's Philosophy of Religion Re-examined (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); an argument against Kant as deist is Stephen Palmquist's "Kant's Theistic Solution".

English deism, in the words of Peter Gay, "travelled well. ... As Deism waned in England, it waxed in France and the German states."[45]

France had its own tradition of religious skepticism and natural theology in the works of Montaigne, Bayle, and Montesquieu. The most famous of the French deists was Voltaire, who acquired a taste for Newtonian science, and reinforcement of deistic inclinations, during a two-year visit to England starting in 1726.

French deists also included Maximilien Robespierre and Rousseau. For a short period of time during the French Revolution the Cult of the Supreme Being was the state religion of France.

Kant's identification with deism is controversial. An argument in favor of Kant as deist is Alan Wood's "Kant's Deism," in P. Rossi and M. Wreen (eds.), Kant's Philosophy of Religion Re-examined (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1991); an argument against Kant as deist is Stephen Palmquist's "Kant's Theistic Solution".

Deism in the United States[edit]

In the United States, Enlightenment philosophy (which itself was heavily inspired by deist ideals) played a major role in creating the principle of religious freedom, expressed in Thomas Jefferson's letters and included in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. American Founding Fathers, or Framers of the Constitution, who were especially noted for being influenced by such philosophy include Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, and Hugh Williamson. Their political speeches show distinct deistic influence.[citation needed]

Other notable Founding Fathers may have been more directly deist. These include James Madison, possibly Alexander Hamilton, Ethan Allen,[46] and Thomas Paine (who published The Age of Reason, a treatise that helped to popularize deism throughout the United States and Europe).

Unlike the many deist tracts aimed at an educated elite, Paine's treatise explicitly appealed to ordinary people, using direct language familiar to the laboring classes. How widespread deism was among ordinary people in the United States is a matter of continued debate.[47]

A major contributor was Elihu Palmer (1764–1806), who wrote the "Bible" of American deism in his Principles of Nature (1801) and attempted to organize deism by forming the "Deistical Society of New York" and other deistic societies from Maine to Georgia.[48]

In the United States there is controversy over whether the Founding Fathers were Christians, deists, or something in between.[49][50] Particularly heated is the debate over the beliefs of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.[51][52][53]

Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography, "Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's lectures. It happened that they wrought an effect on me quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist. My arguments perverted some others, particularly Collins and Ralph; but each of them having afterwards wrong'd me greatly without the least compunction, and recollecting Keith's conduct towards me (who was another freethinker) and my own towards Vernon and Miss Read, which at times gave me great trouble, I began to suspect that this doctrine, tho' it might be true, was not very useful."[54][55] Franklin also wrote that, "The Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc'd in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man."[56] He later stated, in the Constitutional Convention, that "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth -- that God governs in the affairs of men."[57]

For his part, Thomas Jefferson is perhaps one of the Founding Fathers with the most outspoken of deist tendencies, though he is not known to have called himself a deist, generally referring to himself as a Unitarian. In particular, his treatment of the Biblical gospels, which he titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, but subsequently became more commonly known as the Jefferson Bible, exhibits a strong deist tendency of stripping away all supernatural and dogmatic references from the Christ story. However, Frazer, following the lead of Sydney Ahlstrom, characterizes Jefferson as not a Deist but a "theistic rationalist", because Jefferson believed in God's continuing activity in human affairs.[58][59] Frazer cites Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia, where he wrote, "I tremble" at the thought that "God is just," and he warned of eventual "supernatural influence" to abolish the scourge of slavery.[60][61]

In the United States, Enlightenment philosophy (which itself was heavily inspired by deist ideals) played a major role in creating the principle of religious freedom, expressed in Thomas Jefferson's letters and included in the First Amendment to the United States Constitution. American Founding Fathers, or Framers of the Constitution, who were especially noted for being influenced by such philosophy include Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin, Cornelius Harnett, Gouverneur Morris, and Hugh Williamson. Their political speeches show distinct deistic influence.[citation needed]

Other notable Founding Fathers may have been more directly deist. These include James Madison, possibly Alexander Hamilton, Ethan Allen,[46] and Thomas Paine (who published The Age of Reason, a treatise that helped to popularize deism throughout the United States and Europe).

Unlike the many deist tracts aimed at an educated elite, Paine's treatise explicitly appealed to ordinary people, using direct language familiar to the laboring classes. How widespread deism was among ordinary people in the United States is a matter of continued debate.[47]

A major contributor was Elihu Palmer (1764–1806), who wrote the "Bible" of American deism in his Principles of Nature (1801) and attempted to organize deism by forming the "Deistical Society of New York" and other deistic societies from Maine to Georgia.[48]

In the United States there is controversy over whether the Founding Fathers were Christians, deists, or something in between.[49][50] Particularly heated is the debate over the beliefs of Benjamin Franklin, Thomas Jefferson, and George Washington.[51][52][53]

Benjamin Franklin wrote in his autobiography, "Some books against Deism fell into my hands; they were said to be the substance of sermons preached at Boyle's lectures. It happened that they wrought an effect on me quite contrary to what was intended by them; for the arguments of the Deists, which were quoted to be refuted, appeared to me much stronger than the refutations; in short, I soon became a thorough Deist. My arguments perverted some others, particularly Collins and Ralph; but each of them having afterwards wrong'd me greatly without the least compunction, and recollecting Keith's conduct towards me (who was another freethinker) and my own towards Vernon and Miss Read, which at times gave me great trouble, I began to suspect that this doctrine, tho' it might be true, was not very useful."[54][55] Franklin also wrote that, "The Deity sometimes interferes by his particular Providence, and sets aside the Events which would otherwise have been produc'd in the Course of Nature, or by the Free Agency of Man."[56] He later stated, in the Constitutional Convention, that "the longer I live, the more convincing proofs I see of this truth -- that God governs in the affairs of men."[57]

For his part, Thomas Jefferson is perhaps one of the Founding Fathers with the most outspoken of deist tendencies, though he is not known to have called himself a deist, generally referring to himself as a Unitarian. In particular, his treatment of the Biblical gospels, which he titled The Life and Morals of Jesus of Nazareth, but subsequently became more commonly known as the Jefferson Bible, exhibits a strong deist tendency of stripping away all supernatural and dogmatic references from the Christ story. However, Frazer, following the lead of Sydney Ahlstrom, characterizes Jefferson as not a Deist but a "theistic rationalist", because Jefferson believed in God's continuing activity in human affairs.[58][59] Frazer cites Jefferson's Notes on the State of Virginia, where he wrote, "I tremble" at the thought that "God is just," and he warned of eventual "supernatural influence" to abolish the scourge of slavery.[60][61]

Decline and rebirth of deism[edit]

Deism is generally considered to have declined as an influential school of thought by around 1800, but has since experienced an extraordinary resurgence as its simple science- and reason-based philosophy has been rediscovered in the internet Age.

The 2001 American Religious Identification Survey (ARIS), which involved 50,000 participants, reported that the number of participants in the survey identifying themselves as deists grew at the rate of 717 percent between 1990 and 2001. If this were generalized to the US population as a whole, it would make deism the fastest-growing religious classification in the US for that period, with the reported total of 49,000 self-identified adherents representing about 0.02% of the US population in 2001.[62][63]

As of the time of the 2008 ARIS survey, 12 percent (38 million) of the American population were classified as Deists.[64]

It is probably more accurate, however, to say that deism evolved into, and contributed to, other religious movements. The term deist became rarely used, but deist beliefs, ideas, and influences remained. They can be seen in 19th-century liberal British theology and in the rise of Unitarianism, which adopted many of deism's beliefs and ideas.

Although this decline has entirely reversed during the early 21st century, some commentators have suggested a variety of reasons for the former decline of "classical" deism (or perhaps actually simply a decline in the use of the term "Deism", rather than in the more universality Deist philosophy).

- the rise, growth, and spread of naturalism[65] and materialism, which were atheistic

- the writings of David Hume[65][66] and Immanuel Kant[66] (and later, Charles Darwin), which increased doubt about the first cause argument and the argument from design, turning many (though not all) potential deists towards atheism instead

- criticisms (by writers such as Joseph-Marie de Maistre and Edmund Burke) of excesses of the French Revolution, and consequent rising doubts that reason and rationalism could solve all problems[66]

- deism became associated with pantheism, freethought, and atheism, all of which became associated with one another, and were so criticized by Christian apologists[65][66]

- frustration with the determinism implicit in "This is the best of all possible worlds"