Cantore Arithmetic is able to state for word Robots as the word making equated words numbered equating words part, word numbered[Numbered[Mackenzie Warehouse!!].

2. Word Byrd specific[Specific] has word stayed at word creation for both entry, exit, and, word circulation at eyes for nose to counter word breathing componentry.

3. Word Named Beelzebub equated word stop and word halt.

4. Andrew Wommack[© 2025 Andrew Wommack Ministries. All rights reserved. Privacy Policy Terms of Use Return Policy Cookie Policy[word wheel[Wheel[WHEEL]]]]] and his Benbot named after The Benbow Inn has a word wheel and that word wheel goes on in the word box of the exampled ancient word load called The Turk[Mechanical Turk,] equated word as[A Keynote word Speaker; so, Bose® for words host[Host[HOST!!].

Benbow Historic Inn | Garberville Resort | Redwoods Getaway

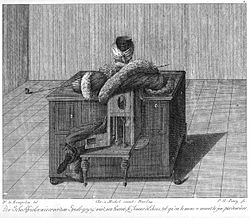

A cross-section of the Turk from Racknitz, showing how he thought the operator sat inside as he played his opponent. Racknitz was wrong both about the position of the operator and the dimensions of the automaton.[1]

5. For the Crazy Horse doctor[Doctor] the wheel[Wheel[WHEEL]] is able at word convenience[math] as the disk[Disk] is word shaped after my Aunt Laura’ word stuff that word they[They] brought with her word separately to the City of San Francisco word from word the words State of Arizona. On Andrew Wommack’ Home Computer the disks’ for all the Presidents’ of the United States of America would be sold separately and word would be available only from The Library of Congress for word efficiency[EFFICIENCY see lab for word dog, word house[HOUSE]].

a.

RCA Victor and Columbia Records

6.(six(Six(NINE))) Words Film[I, Robot (2004) Trailer #1 | Movieclips Classic Trailers (I, Robot Theatrical Trailer from 20th Century Fox)0 © 1990-2025 by IMDb.com, Inc.[Radio Trailer (2003)[Coast to Coast[M R E]]]]04

a. Word This equated word film[Films’[FILMS’]] back ash so[comma[,[Comma]]] word core, word corn, word hot, word cob[Cob[COB]] 14.2 to 15.1 hands

b. Words So, Bob Ross, Inc. is able at word Palette

c. For this example: Bob Ross [bar[Bar[BAR]]] Intro to Show of Painting

1. Words So,[so,[SO,]] horse[Horse[HORSE]]

American Paint Horse Association: A Rich Legacy - APHA ...

The American Paint Horse is a stock-type animal of Paint, Quarter Horse or Thoroughbred lineage; they often sport beautiful white markings on their coats.... Paint Horse. It is a breed of horse that combines both the conformational characteristics of a western stock horse with a pinto spotting ...

8. Words’ tar baby equated word tar[Tar[TAR]] equated word baby[whet[Whet[WHET]]] equated word possible.

a. Word Cancer!!!. to expose word probable as word pyramid to word square via word block as word equated words star of Man named david[Eden[Garden!!expose Kodak at Polaroid on Film as word equated word net[basket

..........; however word basket[Basket[BASKET]] must be word set in word circulation so, Solomon’s Mine!!!!!!!!!!!!!!: WORDS Man holding word equated word loud speaker[TWINE NOW, word chain links; Researcher wants your bobcat or lynx]::

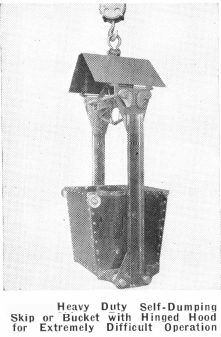

The standard type ore bucket or skip

Cantore Arithmetic is able to state word prayer[Prayer[PRAYER]] equated word binary[Binary[BINARY]] as word diverticulitis[difficult[made[main[tale[braid[laid[made]]]]]]] equated word shuttle[Shuttle[Shuttle]].

1. Word made[Made[MADE] equated words numbered

2. Word tale[Tale[TALE] equated words numbered

b. 5 Instances

1. Strong’s goes here

a.

3. Word laid[Laid[LAID]] equated words numbered[Numbered]

Words Text to word capacitor is able word comprehend as word their[APPLE, Microsoft, and word equated word so on!!] has brought word Manufacturers to word floor.

For the Christian and word Christians as word text[Text[TEXT]] equated word chalk[stock[Stock[STOCK]] equated word board.

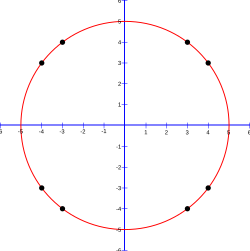

Works of Srinivasa Ramanujan word developed word answer to word equated[unsolvable!!] as words on Wikipedia[... 3.141866 (accuracy 9·10−5). He also suggested that 3.14 was a good enough ... In 1910, the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan found several rapidly ...] equated word only production[word practice]..[made substantial contributions to mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series, and continued fractions, including solutions to mathematical problems then considered unsolvable]; mathematical analysis, number theory, infinite series, and continued fractions, including solutions to mathematical problems then considered unsolvable. Ramanujan initially developed his own mathematical research in isolation. According

Approximations of π

1. : compounded or consisting of or marked by two things or parts.

a. 1 of 2

Mechanical Turk

The Mechanical Turk, also known as the Automaton Chess Player (German: Schachtürke, lit. 'chess Turk'; Hungarian: A Török), or simply The Turk, was a fraudulent chess-playing machine constructed in 1770, which appeared to be able to play a strong game of chess against a human opponent. For 84 years, it was exhibited on tours by various owners as an automaton. The machine survived and continued giving occasional exhibitions until 1854, when a fire swept through the museum where it was kept, destroying the machine. Afterwards, articles were published by a son of the machine's owner revealing its secrets to the public: that it was an elaborate hoax, suspected by some, but never proven in public while it still existed.[2]

Constructed and unveiled in 1770 by Wolfgang von Kempelen (1734–1804) to impress Empress Maria Theresa of Austria, the mechanism appeared to be able to play a strong game of chess against a human opponent, as well as perform the knight's tour, a puzzle that requires the player to move a knight to occupy every square of a chessboard exactly once.

The Turk was in fact a mechanical illusion that allowed a human chess master hiding inside to operate the machine. With a skilled operator, the Turk won most of the games played during its demonstrations around Europe and the Americas for nearly 84 years, playing and defeating many challengers including statesmen such as Napoleon Bonaparte and Benjamin Franklin. The device was later purchased in 1804 and exhibited by Johann Nepomuk Mälzel. The chessmasters who secretly operated it included Johann Allgaier, Boncourt, Aaron Alexandre, William Lewis, Jacques Mouret, and William Schlumberger, but the operators within the mechanism during Kempelen's original tour remain unknown.

Construction

[edit]

Kempelen was inspired to build the Turk following his attendance at the court of Maria Theresa of Austria at Schönbrunn Palace, where François Pelletier was performing an illusion act. An exchange afterward resulted in Kempelen's promise to return to the Palace with an invention that would top the illusions.[3]

The result of the challenge was the Automaton Chess-player,[4][5] later known as the Turk. The machine consisted of a life-sized model of a human head and torso, with a black beard and grey eyes,[6] and dressed in Ottoman robes and a turban—"the traditional costume", according to journalist and author Tom Standage, "of an oriental sorcerer". Its left arm held a long Ottoman smoking pipe when at rest, while its right lay on a large cabinet[7] that measured about 3.5 feet (110 cm) long,[a] 2 feet (61 cm) wide, and 2.5 feet (76 cm) high. Placed on the top of the cabinet was a chessboard, which measured 18 inches (460 mm) on each side. The front of the cabinet consisted of three doors, an opening, and a drawer, which could be opened to reveal a red and white ivory chess set.[8]

The interior of the machine was very complicated and designed to mislead those who observed it.[3] When opened on the left, the front doors of the cabinet exposed a number of gears and cogs similar to clockwork. The section was designed so that if the back doors of the cabinet were open at the same time one could see through the machine. The other side of the cabinet did not house machinery; instead it contained a red cushion and some removable parts, as well as brass structures. This too was designed to provide a clear line of vision through the machine. Underneath the robes of the Ottoman model, two other doors were hidden. These also exposed clockwork machinery and provided a similarly unobstructed view through the machine. The design allowed the presenter of the machine to open every available door to the public, to maintain the illusion.[9]

Neither the clockwork visible to the left side of the machine nor the drawer that housed the chess set extended fully to the rear of the cabinet; they instead went only one third of the way. A sliding seat was also installed, allowing the operator inside to slide from place to place and thus evade observation as the presenter opened various doors. The sliding of the seat caused dummy machinery to slide into its place to further conceal the person inside the cabinet.[10]

The chessboard on the top of the cabinet was thin enough to allow for a magnetic linkage. Each piece in the chess set had a small, strong magnet attached to its base, and when each piece was placed on the board it would attract a magnet attached to a string under its place on the board. This allowed the operator inside the machine to see which pieces moved where on the chess board.[11] The bottom of the chessboard had corresponding numbers, 1–64, allowing the operator to see which places on the board were affected by a player's move.[12]The internal magnets were positioned so that outside magnetic forces did not influence them, and Kempelen would often allow a large magnet to sit at the side of the board in an attempt to show that the machine was not influenced by magnetism.[13]

As a further means of misdirection, the Turk came with a small wooden coffin-like box that the presenter would place on the top of the cabinet.[3] While Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, a later owner of the machine, did not use the box,[14] Kempelen often peered into the box during play, suggesting that the box controlled some aspect of the machine.[3] The box was believed by some to have supernatural power; Karl Gottlieb von Windisch wrote in his 1784 book Inanimate Reason that "[o]ne old lady, in particular, who had not forgotten the tales she had been told in her youth ... went and hid herself in a window seat, as distant as she could from the evil spirit, which she firmly believed possessed the machine."[5]

The interior also contained a pegboard chess board connected to a pantograph-style series of levers that controlled the model's left arm. The metal pointer on the pantograph moved over the interior chessboard, and would simultaneously move the arm of the Turk over the chessboard on the cabinet. The range of motion allowed the operator to move the Turk's arm up and down, and turning the lever would open and close the Turk's hand, allowing it to grasp the pieces on the board. All of this was made visible to the operator by using a simple candle, which had a ventilation system through the model.[15] Other parts of the machinery made a sound like clockwork when the Turk made a move, further adding to the machinery illusion,[16] and for the Turk to make various facial expressions.[17] A voice box was added following the Turk's acquisition by Mälzel, allowing the machine to say "Échec!" (French for "check") during matches.[4]

An operator inside the machine also had tools to assist in communicating with the presenter outside. Two brass discs equipped with numbers were positioned opposite each other on the inside and outside of the cabinet. A rod could rotate the discs to the desired number, which acted as a code between the two.[18]

Exhibition

[edit]The Turk made its debut in 1770 at Schönbrunn Palace, about six months after Pelletier's act. Kempelen addressed the court, presenting what he had built, and began the demonstration of the machine and its parts. With every showing of the Turk, Kempelen began by opening the doors and drawers of the cabinet, allowing members of the audience to inspect the machine. Following this display, Kempelen would announce that the machine was ready for a challenger.[19]

Kempelen would inform the player that the Turk would use the white pieces and have the first move. (The convention that White moves first was not yet established, so there was no redundancy.) Between moves the Turk kept its left arm on the cushion. The Turk could nod twice if it threatened its opponent's queen, and three times upon placing the king in check. If an opponent made an illegal move, the Turk would shake its head, move the piece back and make its own move, thus forcing a forfeit of its opponent's move.[20]Louis Dutens, a traveller who observed a showing of the Turk, attempted to trick the machine "by giving the Queen the move of a Knight, but my mechanic opponent was not to be so imposed upon; he took up my Queen and replaced her in the square from which I had moved her".[21] Kempelen made it a point to traverse the room during the match, and invited observers to bring magnets, irons, and lodestones to the cabinet to test whether the machine was run by magnets or weights. The first person to play against the Turk was Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, an Austrian courtier at the palace. Along with other challengers that day, he was quickly defeated, with observers of the match stating that the machine played aggressively, and typically beat its opponents within thirty minutes.[22]

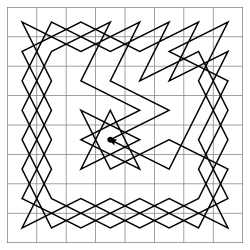

Another part of the machine's exhibition was the completion of the knight's tour, a famed chess puzzle. The puzzle requires the player to move a knight around a chessboard, touching each square once along the way. While most experienced chess players of the time still struggled with the puzzle, the Turk was capable of completing the tour without any difficulty from any starting point via a pegboard used by the operator with a mapping of the puzzle laid out.[23]

The Turk could also converse with spectators using a letter board. The operator, whose identity during the period when Kempelen presented the machine at Schönbrunn Palace is unknown,[24] was able to do this in English, French, and German. Carl Friedrich Hindenburg, a university mathematician, kept a record of the conversations during the Turk's time in Leipzig and published it in 1789 as Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung (or On the Chessplayer of Mr. von Kempelen and Its Replica). Topics of questions put to and answered by the Turk included its age, marital status, and secret workings.[25]

Tour of Europe

[edit]Following word of its debut, interest in the machine grew across Europe. Kempelen, however, was more interested in his other projects and avoided exhibiting the Turk, often lying about the machine's repair status to prospective challengers. Von Windisch wrote at one point that Kempelen "refused the entreaties of his friends, and a crowd of curious persons from all countries, the satisfaction of seeing this far-famed machine".[26] In the decade following its debut at Schönbrunn Palace the Turk only played one opponent, Sir Robert Murray Keith, a Scottish noble, and Kempelen went as far as dismantling the Turk entirely following the match.[27] Kempelen was quoted as referring to the invention as a "mere bagatelle", as he was not pleased with its popularity and would rather continue work on steam engines and machines that replicated human speech.[28]

In 1781, Kempelen was ordered by Emperor Joseph II to reconstruct the Turk and deliver it to Vienna for a state visit from Grand Duke Paul of Russia and his wife. The appearance was so successful that Grand Duke Paul suggested a tour of Europe for the Turk, a request to which Kempelen reluctantly agreed.[29]

The Turk began its European tour in 1783, beginning with an appearance in France in April. A stop at Versailles beginning on 17 April, preceded an exhibition in Paris, where the Turk lost a match to Charles Godefroy de La Tour d'Auvergne, the Duc de Bouillon. Upon arrival in Paris in May 1783, it was displayed to the public and played a variety of opponents, including a lawyer named Mr. Bernard who was a second rank in chess ability.[30] Following the sessions at Versailles, demands increased for a match with François-André Danican Philidor, who was considered the best chess player of his time.[31] Moving to the Café de la Régence, the machine played many of the most skilled players, often losing (e.g. against Bernard and Verdoni),[32] until securing a match with Philidor at the Académie des Sciences. While Philidor won his match with the Turk, Philidor's son noted that his father called it "his most fatiguing game of chess ever!"[33] The Turk's final game in Paris was against Benjamin Franklin, who was serving as ambassador to France from the United States. Franklin reportedly enjoyed the game with the Turk and was interested in the machine for the rest of his life, keeping a copy of Philip Thicknesse's book The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected in his personal library.[34]

Following his tour of Paris, Kempelen moved the Turk to London, where it was exhibited daily for five shillings. Thicknesse, known in his time as a skeptic, sought out the Turk in an attempt to expose the inner workings of the machine.[35] While he respected Kempelen as "a very ingenious man",[3] he asserted that the Turk was an elaborate hoax with a small child inside the machine, describing the machine as "a complicated piece of clockwork ... which is nothing more, than one, of many other ingenious devices, to misguide and delude the observers".[36]

After a year in London, Kempelen and the Turk travelled to Leipzig, stopping in various European cities along the way. From Leipzig, it went to Dresden, where Joseph Friedrich Freiherr von Racknitz viewed the Turk and published his findings in Über den Schachspieler des Herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung (On Mr. von Kempelen’s chess player and its replica), along with illustrations showing his beliefs about how the machine operated.[37] It then moved to Amsterdam, after which Kempelen is said to have accepted an invitation to the Sanssouci palace in Potsdam of Frederick the Great, King of Prussia. The story goes that Frederick enjoyed the Turk so much that he paid a large sum of money to Kempelen in exchange for the Turk's secrets. Frederick never gave the secret away, but was reportedly disappointed to learn how the machine worked.[38] This story is apocryphal; there is no evidence of the Turk's encounter with Frederick, the first mention of which comes in the early 19th century, by which time the Turk was incorrectly said to have played against George III of Great Britain.[39] It seems most likely that the machine stayed dormant at Schönbrunn Palace for over two decades, although Kempelen attempted unsuccessfully to sell it in his final years. Kempelen died at the age of 70 on 26 March 1804.[40]

Mälzel and the machine

[edit]Following the death of Kempelen, the Turk remained unexhibited until 1805 when Kempelen's son decided to sell it to Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, a Bavarian musician with an interest in various machines and devices. Mälzel, whose successes included patenting a form of metronome, had tried to purchase the Turk once previously, before Kempelen's death. The original attempt had failed, owing to Kempelen's asking price of 20,000 francs; Kempelen's son sold the machine to Mälzel for half this sum.[41] Upon acquiring the Turk, Mälzel had to learn its secrets and make some repairs to get it back in working order. His stated goal was to make explaining the Turk a greater challenge. While the completion of this goal took ten years, the Turk still made appearances, most notably with Napoleon Bonaparte.[42]

In 1809, Napoleon I of France arrived at Schönbrunn Palace to play the Turk. According to an eyewitness report, Mälzel took responsibility for the construction of the machine while preparing the game, and the Turk (Johann Baptist Allgaier) saluted Napoleon before the start of the match. The details of the match have been published over the years in numerous accounts, many of them contradictory.[43] According to Bradley Ewart, it is believed that the Turk sat at its cabinet, and Napoleon sat at a separate chess table. Napoleon's table was in a roped-off area and he was not allowed to cross into the Turk's area, with Mälzel crossing back and forth to make each player's move and allowing a clear view for the spectators. In a surprise move, Napoleon took the first turn instead of allowing the Turk to make the first move, as was usual; but Mälzel allowed the game to continue. Shortly thereafter, Napoleon attempted an illegal move. Upon noticing the move, the Turk returned the piece to its original spot and continued the game. Napoleon attempted the illegal move a second time, and the Turk responded by removing the piece from the board entirely and taking its turn. Napoleon then attempted the move a third time, the Turk responding with a sweep of its arm, knocking all the pieces off the board. Napoleon was reportedly amused, and then played a real game with the machine, completing nineteen moves before tipping over his king in surrender.[44] Alternate versions of the story include Napoleon being unhappy about losing to the machine, playing the machine at a later time, playing one match with a magnet on the board, and playing a match with a shawl around the head and body of the Turk in an attempt to obscure its vision.[45]

In 1811, Mälzel brought the Turk to Milan for a performance with Eugène de Beauharnais, the Prince of Venice and Viceroy of Italy. Beauharnais enjoyed the machine so much that he offered to purchase it from Mälzel. After some serious bargaining, Beauharnais acquired the Turk for 30,000 francs—three times what Mälzel had paid—and kept it for four years. In 1815, Mälzel returned to Beauharnais in Munich and asked to buy the Turk back. There exist two versions of how much he had to pay, eventually working out an agreement.[46] One version appeared in the French periodical Le Palamède.[b] The complete story does not make a lot of sense since Mälzel visited Paris again, and he also could import his "Conflagration of Moscow".[c]

Following the repurchase, Mälzel brought the Turk back to Paris, where he made acquaintances of many of the leading chess players at Café de la Régence. Mälzel stayed in France with the machine until 1818, when he moved to London and held a number of performances with the Turk and many of his other machines. In London, Mälzel and his act received a large amount of press, and he continued improving the machine,[50] ultimately installing a voice box so the machine could say "Échec!" when placing a player in check.[51]

In 1819, Mälzel took the Turk on a tour of the United Kingdom. There were several new developments in the act, such as allowing the opponent the first move and eliminating the king's bishop's pawn from the Turk's pieces. This pawn handicap created further interest in the Turk, and spawned a book by W. J. Hunneman chronicling the matches played with this handicap.[52] Despite the handicap, the Turk (operated by Mouret at the time)[53] ended up with forty-five victories, three losses, and two stalemates.[54]

Mälzel in North America

[edit]The appearances of the Turk were profitable for Mälzel, and he continued by taking it and his other machines to the United States. In 1826, he opened an exhibition in New York City that slowly grew in popularity, giving rise to many newspaper stories and anonymous threats of exposure of the secret. Mälzel's problem was finding a proper operator for the machine,[55] having trained an unknown woman in France before coming to the United States. He ended up recalling a former operator, William Schlumberger, from Alsace in Europe to come to America and work for him again once Mälzel was able to provide the money for Schlumberger's transport.

Upon Schlumberger's arrival, the Turk debuted in Boston, Mälzel spinning a story that the New York chess players could not handle full games and that the Boston players were much better opponents.[56] This was a success for many weeks, and the tour moved to Philadelphia for three months. Following Philadelphia, the Turk moved to Baltimore, where it played for a number of months, including losing a match against Charles Carroll, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. The exhibition in Baltimore brought news that two brothers had constructed their own machine, the Walker Chess-player. Mälzel viewed the competing machine and attempted to buy it, but the offer was declined and the duplicate machine toured for a number of years, never receiving the fame that Mälzel's machine did and eventually falling into obscurity.[57]

Mälzel continued with exhibitions around the United States until 1828, when he took some time off and visited Europe, returning in 1829. Throughout the 1830s, he continued to tour the United States, exhibiting the machine as far west as the Mississippi River and visiting Canada. In Richmond, Virginia, the Turk was observed by Edgar Allan Poe, who was writing for the Southern Literary Messenger. Poe's essay "Maelzel's Chess Player" was published in April 1836 and is the most famous essay on the Turk, even though many of Poe's hypotheses were incorrect (such as that a chess-playing machine must always win).[58]

Mälzel eventually took the Turk on his second tour to Havana, Cuba. In Cuba, Schlumberger died of yellow fever in February 1838, leaving Mälzel without an operator for his machine. Dejected, Mälzel died at sea in July 1838 at the age of 65 during his return trip, leaving his machinery with the ship captain.[59][60]

Final years and beyond

[edit]

When the ship on which Mälzel died returned, his various machines, including the Turk, fell into the hands of Mälzel's friend, the businessman John Ohl. He attempted to auction off the Turk, but owing to low bidding ultimately bought it himself for $400 (equivalent to $12,000 in 2024).[61] Only when John Kearsley Mitchell from Philadelphia, Edgar Allan Poe's personal physician and an admirer of the Turk, approached Ohl did the Turk change hands again.[3]Mitchell formed a restoration club and went about the business of repairing the Turk for public appearances, completing the restoration in 1840.[62]

As interest in the Turk outgrew its location, Mitchell and his club chose to donate the machine to the Philadelphia Museum of Charles Willson Peale, also known as the Chinese Museum. While the Turk still occasionally gave performances, it was eventually relegated to the corners of the museum and forgotten about until 5 July 1854, when a fire that started at the National Theater in Philadelphia reached the Museum and destroyed the Turk.[63] Mitchell's son Silas Weir Mitchell believed he had heard "through the struggling flames ... the last words of our departed friend, the sternly whispered, oft repeated syllables, 'echec! echec!!'"[64]

John Gaughan, an American manufacturer of equipment for magicians based in Los Angeles, spent $120,000 (equivalent to $360,000 in 2024) building his own version of Kempelen's machine over a five-year period from 1984-89.[65] The machine uses the original chessboard, which was stored separately from the original Turk and was not destroyed in the fire. The first public display of Gaughan's Turk was in November 1989 at the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History. The machine was presented much as Kempelen presented the original, except that the opponent was replaced by a computer running a chess program.[66]

Revealing the secrets

[edit]While many books and articles were written during the Turk's life about how it worked, most were inaccurate, drawing incorrect inferences from external observation. The first articles on the mechanism were published in a French magazine entitled Le Magasin pittoresque in 1834.[67] It was not until Silas Mitchell's series of articles for The Chess Monthly in 1857 that the secret was fully revealed. Mitchell, son of the final private owner of the Turk,[68] wrote that "no secret was ever kept as the Turk's has been. Guessed at, in part, many times, no one of the several explanations ... ever solved this amusing puzzle". As the Turk was lost to fire at the time of this publication, Silas Mitchell felt that there were "no longer any reasons for concealing from the amateurs of chess, the solution to this ancient enigma".[64]

The most important biographical history about the Chess-player and Mälzel was presented in The Book of the First American Chess Congress, published by Daniel Willard Fiske in 1857.[60] The account, "The Automaton Chess-Player in America", was written by Professor George Allen of Philadelphia, in the form of a letter to William Lewis, one of the former operators of the chess automaton.

In 1859, a letter published in the Philadelphia Sunday Dispatch by William F. Kummer, who worked as an operator under John Mitchell, revealed another piece of the secret: a candle inside the cabinet, necessary to provide light for the operator. A series of tubes led from the lamp to the turban of the Turk for ventilation. The smoke rising from the turban would be disguised by the smoke coming from the other candelabra in the area where the game was played.[69]

Later in 1859, an uncredited article appeared in Littell's Living Age that purported to be the story of the Turk from French magician Jean Eugène Robert-Houdin. This was rife with errors ranging from dates of events to a story of a Polish officer whose legs were amputated, but ended up being rescued by Kempelen and smuggled back to Russia inside the machine.[70]

A new article about the Turk did not turn up until 1899, when The American Chess Magazine published an account of the Turk's match with Napoleon Bonaparte. The story was basically a review of previous accounts, and a substantive published account would not appear until 1947, when Chess Review published articles by Kenneth Harkness and Jack Straley Battell that amounted to a comprehensive history and description of the Turk, complete with new diagrams that synthesized information from previous publications. Another article written in 1960 for American Heritage by Ernest Wittenberg provided new diagrams describing how the operator sat inside the cabinet.[71]

In Henry A. Davidson's 1945 publication A Short History of Chess, significant weight is given to Poe's essay which erroneously suggested that the player sat inside the Turk figure, rather than on a moving seat inside the cabinet. A similar error would occur in Alex G. Bell's 1978 book The Machine Plays Chess, which falsely asserted that "the operator was a trained boy (or very small adult) who followed the directions of the chess player who was hidden elsewhere on stage or in the theater ..."[72]

More books were published about the Turk toward the end of the 20th century. Along with Bell's book, Charles Michael Carroll's The Great Chess Automaton (1975) focused more on the studies of the Turk. Bradley Ewart's Chess: Man vs. Machine (1980) discussed the Turk as well as other purported chess-playing automatons.[73]

It was not until the creation of Deep Blue, IBM's attempt at a computer that could challenge the world's best players,[74] that interest increased again, and two more books were published: Gerald M. Levitt's The Turk, Chess Automaton (2000),[d] and Tom Standage's The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine (2002).[e] The Turk was used as a personification of Deep Blue in the 2003 documentary Game Over: Kasparov and the Machine.

Legacy and popular culture

[edit]

Owing to the Turk's popularity and mystery, its construction inspired a number of inventions and imitations,[3] including Ajeeb, or "The Egyptian", an American imitation built by Charles Hopper that President Grover Cleveland played in 1885,[75] and Mephisto, advertised as the "most famous" machine, of which little is known.[76] The first imitation was made while Mälzel was in Baltimore. Created by the Brothers Walker, the "American Chess Player" made its debut in May 1827 in New York.[77] El Ajedrecista was built in 1912 by Leonardo Torres Quevedo as a chess-playing automaton and made its public debut during the Paris World Fair of 1914. Capable of playing rook and king versus king endgames using electromagnets, it was the first true chess-playing automaton, and a precursor of sorts to Deep Blue.[75]

The Turk was visited in London by Rev. Edmund Cartwright in 1784. He was so intrigued by the Turk that he would later question whether "it is more difficult to construct a machine that shall weave than one which shall make all the variety of moves required in that complicated game". Cartwright would patent the prototype for a power loom within the year.[78] Sir Charles Wheatstone, an inventor, saw a later appearance of the Turk while it was owned by Mälzel. He also saw some of Mälzel's speaking machines, and Mälzel later presented a demonstration of the speaking machines to the researcher and his teenage son. Alexander Graham Bell obtained a copy of a book by Wolfgang von Kempelen on speaking machines after being inspired by seeing a similar machine built by Wheatstone; Bell went on to file the first successful patent for the telephone.[3]

A play, The Automaton Chess Player, was presented in New York City in 1845. The advertising, as well as an article that appeared in The Illustrated London News, claimed that the play featured Kempelen's Turk, but it was in fact a copy of the Turk created by J. Walker, who had earlier presented the Walker Chess-player.[79]

In Raymond Bernard's silent feature film The Chess Player (1927), a young Polish nationalist on the run from the occupying Russians is hidden inside a chess-playing automaton closely based on the real Kempelen model.[80]

The Turk has also inspired works of literary fiction. In 1849, just a few years before the Turk was destroyed, Edgar Allan Poepublished a tale "Von Kempelen and His Discovery".[81] Ambrose Bierce's short story "Moxon's Master", published in 1909, is a morbid tale about a chess-playing automaton that resembles the Turk. In 1938, John Dickson Carr published The Crooked Hinge,[82]among whose puzzles is an automaton that operates in a way that is unexplainable to the characters.[83] Gene Wolfe's 1977 science fiction short story "The Marvellous Brass Chessplaying Automaton" also features a device very similar to the Turk.[84] Robert Loehr's2007 novel The Chess Machine (published in the UK as The Secrets of the Chess Machine) focuses on the man inside the machine. F. Gwynplaine MacIntyre's 2007 story "The Clockwork Horror" reconstructs Edgar Allan Poe's encounter with Mälzel's chess-player, and also establishes (from contemporary advertisements in a Richmond newspaper) precisely when and where this took place.[85]

In 2005, Amazon launched Amazon Mechanical Turk, an online service using remote human labor hidden behind a computer interface to help employers perform tasks impossible for a true machine, roughly analogous to the original Mechanical Turk.

In June 2024, chess.com announced that one of the monthly bots would be named The Mechanical Turk. It was given a rating of "?" with the description: "Created in 1770, The Mechanical Turk was the first ever chess robot. But why do we hear sneezes from his stomach? Play him and see if you can unravel this month's secret..."[86]

In the first thesis of his Theses on the Philosophy of History (Über den Begriff der Geschichte), written in 1940, Walter Benjamin writes of the Mechanical Turk:[87]

Notes

[edit]- ^ These dimensions are taken from Jay's Journal, which expresses them to the nearest half-foot. Metric versions thus can only be precise to the nearest multiple of fifteen centimetres. If conventionally rounded to the closest multiple of five centimetres, the cabinet was very roughly 110 cm × 60 cm × 75 cm (43 in × 24 in × 30 in), and the chessboard very roughly 2,500 cm2 (390 sq in).

- ^ "The writer in the Palamède makes the result a kind of partnership in an exhibition tour—the title of the Automaton was to remain in the princely owner, and Maelzel was to pay the interest of the original cost as his partner's fair proportion of the profits. But another account—current, I believe, at Munich—makes the transaction to have been a sale: Maelzel bought back the Automaton for the same thirty thousand francs, and was to pay for it out of the profits of his exhibitions—'Provided, nevertheless,' that Maelzel was not to leave the Continent to give such exhibitions. The latter account I believe to be the more correct one."[47]: 426

- ^ "Mr. Maelzel, who had already experienced some regret at parting with his protégé, requested the favour to be again reinstated in the charge, promising to pay Eugene the interest of the thirty thousand francs Mr. M. had pocketed. This proposition was graciously conceded by the gallant Beauharnois, and Maelzel thus had the satisfaction of finding he had made a tolerably good bargain, getting literally the money for nothing at all! Leaving Bavaria with the Automaton, Maelzel was once more en route, as travelling showman of the wooden genius. Other automata were adopted into the family, and a handsome income was realised by their ingenious proprietor. Himself an inferior player, he called the assistance of first-rate talent to the field as his ally. On limits compel us to skip over some interval of time here, during which M. Boncourt (we believe) was Maelzel's chef in Paris, where the machine was received with all its former favour; and we take up the subject in 1819, when Maelzel again appeared with the Chess Automaton in London."[48]

- ^ "The Turk, Chess Automaton". Product listing. McFarland Publishers. Archived from the original on 15 October 2006. Retrieved 1 January2007.

- ^ "The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine". Product listing. Walker Books. Archived from the original on 31 December 2006. Retrieved 1 January 2007.

Citations

[edit]- ^ a b Standage, 88.

- ^ See Schaffer, Simon (1999), "Enlightened Automata", in Clark et al. (eds), The Sciences in Enlightened Europe, Chicago and London, The University of Chicago Press, pp. 126–165.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Ricky Jay, "The Automaton Chess Player, the Invisible Girl, and the Telephone", Jay's Journal of Anomalies, vol. 4 no. 4, 2000.

- ^ a b [Edgar Allan Poe] (April 1836). "Maelzel's Chess-Player". Southern Literary Messenger. 2 (5): 318–326; available on the internet via the Edgar Allan Poe Society of Baltimore, Maryland, URL accessed 19 December 2006.

- ^ a b Karl Gottlieb von Windisch, Briefe über den Schachspieler von Kempelen nebst drey Kupferstichen die diese berühmte Maschine vorstellen, or Inanimate Reason; or, A Circumstantial Account of that Astonishing Piece of Mechanism, M. de Kempelen's Chess-Player, Now Exhibiting at No. 9 Savile-Row, Burlington Gardens(London, 1784); translation taken from Levitt.

- ^ Stephen Patrick Rice, Minding the Machine: Languages of Class in Early Industrial America (Berkeley, University of California Press, 2004), 12.

- ^ Tom Standage, The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous Eighteenth-Century Chess-Playing Machine (New York: Walker, 2002), 22–23.

- ^ Standage, 24.

- ^ Standage, 24–27.

- ^ Standage, 195–199.

- ^ Standage, 202.

- ^ G.W. (1839). "Anatomy of the Chess Automaton". Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country. James Fraser. pp. 717–731.

- ^ Thomas Leroy Hankins and Robert J. Silverman, Instruments and the Imagination (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1995), 191.

- ^ Gerald M. Levitt, The Turk, Chess Automaton (Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland, 2000), 40.

- ^ Levitt, 147–150.

- ^ Standage, 27–29.

- ^ George Atkinson, Chess and Machine Intuition (Exeter: Intellect, 1998), 15–16.

- ^ Standage, 203–204.

- ^ Standage, 24–17.

- ^ Levitt, 17.

- ^ Louis Dutens, from a letter published in Le Mercure du France(Paris, circa October 1770; later translated into English and reprinted in Gentleman's Magazine (London); translation taken from Levitt.

- ^ Standage, 30.

- ^ a b Standage, 30–31.

- ^ Standage, 204–205.

- ^ Levitt, 33–34.

- ^ Standage, 37.

- ^ Standage, 36–38.

- ^ Hamilton, Sheryl (2013) "Invented Humans: Kinship and Property in Persons" In: Impersonations: Troubling the Person in Law and Culture, University of Toronto Press, ISBN 978-1-4426-6964-2

- ^ Standage, 40–42.

- ^ Standage, 44–45.

- ^ Standage, 49.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld, 431–433.

- ^ Levitt, 26.

- ^ Levitt, 27–29.

- ^ Levitt, 30–31.

- ^ Philip Thicknesse, The Speaking Figure and the Automaton Chess Player, Exposed and Detected (London, 1794), quoted in Levitt's The Turk, Chess Automaton.

- ^ Ueber den Schachspieler des herrn von Kempelen und dessen Nachbildung. J.G.I. Breitkopf. 1789.

- ^ Levitt, 33–37.

- ^ Standage, 90–91.

- ^ Levitt, 37–38.

- ^ Levitt, 38–39.

- ^ Levitt, 30.

- ^ Standage, 105–106.

- ^ Bradley Ewart, Chess: Man vs. Machine (London: Tantivy, 1980).

- ^ Levitt, 39–42.

- ^ Levitt, 23–42.

- ^ Willard Fiske, Daniel (1859). "The History of the Automaton Chess-Player in America". The Book of the First American Chess Congress. New York: Rudd & Carleton.

- ^ Fraser's Magazine for Town and Country, volume 19, number 114 (June 1839), p. 726. Online

- ^ Levitt, 45.

- ^ Levitt, 45–48.

- ^ Standage, 125.

- ^ W. J. Hunneman, Chess. A Selection of Fifty Games, from Those Played by the Automaton Chess-Player, During Its Exhibition in London, in 1820 (1820); quotation taken from Levitt.

- ^ Hooper & Whyld, 265.

- ^ Levitt, 49.

- ^ Levitt, 68–69.

- ^ In Boston in 1826 the automaton chess player appeared at Julien Hall. (cf. Boston Commercial Gazette, 14 Sept. 1826)

- ^ Levitt, 71–83.

- ^ Levitt, 83–86.

- ^ Levitt, 87–91.

- ^ a b Daniel Willard Fiske (1859). The Book of the first American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857. Rudd & Carleton. pp. 420–483.

- ^ Levitt, 92–93.

- ^ Levitt, 94–95.

- ^ Levitt, 97.

- ^ a b S[ilas] W[eir] Mitchell (January 1857). "The Last of a Veteran Chess Player". The Chess Monthly. Vol. 1. pp. 3–7. hdl:2027/hvd.hn43vw; continued in February 1857. pp. 40–45. Reprinted: Levitt, 236–240, "Appendix L. Mitchell's 'The Last of a Veteran Chess Player' (1857)."

- ^ Levitt, 243.

- ^ Standage, 216–217.

- ^ Rob Saunders; et al. (2010). Curious Whispers: An Embodied Artificial Creative System. Lisbon, Portugal: Proceedings of the International Conference on Computational Creativity. p. 101. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.1085.1952. ISBN 9789899600126.

- ^ Levitt, 236.

- ^ Levitt, 150.

- ^ Levitt, 151.

- ^ Levitt, 151–152.

- ^ Levitt, 153.

- ^ Levitt, 154–155.

- ^ Feng-hsiung Hsu, Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion (Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 2002).

- ^ a b Ramón Jiménez, "The Rook Endgame Machine of Torres y Quevedo". ChessBase, 20 July 2004. Accessed 15 January 2006.

- ^ Levitt, 154.

- ^ Daniel Willard Fiske (1859). The Book of the first American Chess Congress: Containing the Proceedings of that celebrated Assemblage, held in New York, in the Year 1857. Rudd & Carleton. p. 456.

- ^ Levitt, 31–32.

- ^ Levitt, 241–242.

- ^ Maureen Furniss, "Le Joueur d'Echecs/The Chess Player(review)", The Moving Image 4, no. 1, Spring 2004, pp. 149–151.

- ^ Sova, Dawn B. (2001). Edgar Allan Poe: A to Z. New York: Checkmark Books. ISBN 0-8160-4161-X. Available at Wikisource.

- ^ "Mystery of the Month". Time, 31 October 1938. Accessed 14 February 2007.

- ^ S. T. Joshi, John Dickson Carr: A Critical Study. Bowling Green Press, 1990.

- ^ Terry Carr (editor), Universe 7. Doubleday, 1977.

- ^ James Robert Smith & Stephen Mark Rainey (editors), Evermore, Arkham House, 2007; reprinted in Stephen Jones (editor), The Mammoth Book of Best New Horror, Carroll & Graf, 2007.

- ^ Chess.com announcement

- ^ Walter Benjamin (1968). Illuminations. Schocken. p. 253. ISBN 978-0-8052-0241-0.

References

[edit]- Ewart, Bradley (1980). Chess, man vs. machine. A S Barnes & Co. ISBN 0-498-02167-X.

- Hankins, Thomas L.; Silverman, Robert J. (1995). Instruments and the Imagination. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02997-9.

- Hooper, David; Whyld, Kenneth (1996) [First pub. 1992]. The Oxford Companion to Chess (2nd ed.). Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-280049-3.

- Hsu, Feng-hsiung (2002). Behind Deep Blue: Building the Computer that Defeated the World Chess Champion. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-09065-8.

- Levitt, Gerald M. (2000). The Turk, chess automaton. McFarland & Co Inc Pub. ISBN 0-7864-0778-6.

- Löhr, Robert; Bell, Anthea (5 July 2007). The chess machine. Penguin Group USA. ISBN 978-1-59420-126-4.

- Rice, Stephen Patrick (2004). Minding the Machine: Languages of Class in Early Industrial America. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22781-1.

- Standage, Tom (1 April 2002). The Turk: The Life and Times of the Famous 19th Century Chess-Playing Machine. Walker. ISBN 978-0-8027-1391-9.

- Wood, Gaby (2002). Living Dolls: A Magical History of the Quest for Mechanical Life. Faber & Faber. ISBN 978-0-571-17879-7.

External links

[edit]- Mechanical Turk player profile and games at Chessgames.com

- Dunning, Brian (21 July 2015). "Skeptoid #476: The Chess-Playing Mechanical Turk". Skeptoid.

You searched for

"BOARD" in the KJV Bible

10 Instances - Page 1 of 1 - Sort by Book Order - Feedback

- Exodus 36:21chapter context similar meaning copy save

- The length of a board was ten cubits, and the breadth of a board one cubit and a half.

- Exodus 26:16chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Ten cubits shall be the length of a board, and a cubit and a half shall be the breadth of one board.

- Exodus 26:25chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And they shall be eight boards, and their sockets of silver, sixteen sockets; two sockets under one board, and two sockets under another board.

- Exodus 26:21chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And their forty sockets of silver; two sockets under one board, and two sockets under another board.

- Exodus 36:26chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And their forty sockets of silver; two sockets under one board, and two sockets under another board.

- Exodus 26:19chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And thou shalt make forty sockets of silver under the twenty boards; two sockets under one board for his two tenons, and two sockets under another board for his two tenons.

- Exodus 36:24chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And forty sockets of silver he made under the twenty boards; two sockets under one board for his two tenons, and two sockets under another board for his two tenons.

- Exodus 36:22chapter context similar meaning copy save

- One board had two tenons, equally distant one from another: thus did he make for all the boards of the tabernacle.

- Exodus 26:17chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Two tenons shall there be in one board, set in order one against another: thus shalt thou make for all the boards of the tabernacle.

- Exodus 36:30chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And there were eight boards; and their sockets were sixteen sockets of silver, under every board two sockets.

You searched for

"MADE" in the KJV Bible

1,311 Instances - Page 1 of 44 - Sort by Book Order - Feedback

- John 1:3chapter context similar meaning copy save

- All things were made by him; and without him was not any thing made that was made.

- Job 16:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But now he hath made me weary: thou hast made desolate all my company.

- 1 Kings 7:40chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And Hiram made the lavers, and the shovels, and the basons. So Hiram made an end of doing all the work that he made king Solomon for the house of the LORD:

- Ezra 4:19chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And I commanded, and search hath been made, and it is found that this city of old time hath made insurrection against kings, and that rebellion and sedition have been made therein.

- Psalms 7:15chapter context similar meaning copy save

- He made a pit, and digged it, and is fallen into the ditch which he made.

- Romans 4:14chapter context similar meaning copy save

- For if they which are of the law be heirs, faith is made void, and the promise madeof none effect:

- 2 Chronicles 4:14chapter context similar meaning copy save

- He made also bases, and lavers made he upon the bases;

- 2 Kings 17:30chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And the men of Babylon made Succothbenoth, and the men of Cuth made Nergal, and the men of Hamath made Ashima,

- Exodus 32:35chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And the LORD plagued the people, because they made the calf, which Aaron made.

- Jeremiah 12:11chapter context similar meaning copy save

- They have made it desolate, and being desolate it mourneth unto me; the whole land is made desolate, because no man layeth it to heart.

- Galatians 4:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But when the fulness of the time was come, God sent forth his Son, made of a woman, made under the law,

- Exodus 36:35chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he made a vail of blue, and purple, and scarlet, and fine twined linen: with cherubims made he it of cunning work.

- Exodus 37:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he made two cherubims of gold, beaten out of one piece made he them, on the two ends of the mercy seat;

- Philippians 2:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But made himself of no reputation, and took upon him the form of a servant, and was made in the likeness of men:

- Exodus 36:14chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he made curtains of goats' hair for the tent over the tabernacle: eleven curtains he made them.

- Romans 5:19chapter context similar meaning copy save

- For as by one man's disobedience many were made sinners, so by the obedience of one shall many be made righteous.

- Ezra 6:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Then Darius the king made a decree, and search was made in the house of the rolls, where the treasures were laid up in Babylon.

- Acts 17:24chapter context similar meaning copy save

- God that made the world and all things therein, seeing that he is Lord of heaven and earth, dwelleth not in temples made with hands;

- Joel 1:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- He hath laid my vine waste, and barked my fig tree: he hath made it clean bare, and cast it away; the branches thereof are made white.

- Mark 14:58chapter context similar meaning copy save

- We heard him say, I will destroy this temple that is made with hands, and within three days I will build another made without hands.

- Romans 16:26chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But now is made manifest, and by the scriptures of the prophets, according to the commandment of the everlasting God, made known to all nations for the obedience of faith:

- 1 Kings 10:27chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And the king made silver to be in Jerusalem as stones, and cedars made he to be as the sycomore trees that are in the vale, for abundance.

- 1 Kings 12:31chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he made an house of high places, and made priests of the lowest of the people, which were not of the sons of Levi.

- Ezekiel 27:6chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Of the oaks of Bashan have they made thine oars; the company of the Ashurites have made thy benches of ivory, brought out of the isles of Chittim.

- 2 Corinthians 5:11chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Knowing therefore the terror of the Lord, we persuade men; but we are mademanifest unto God; and I trust also are made manifest in your consciences.

- Matthew 9:22chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But Jesus turned him about, and when he saw her, he said, Daughter, be of good comfort; thy faith hath made thee whole. And the woman was made whole from that hour.

- 1 Corinthians 15:45chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And so it is written, The first man Adam was made a living soul; the last Adam was made a quickening spirit.

- Exodus 37:12chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Also he made thereunto a border of an handbreadth round about; and made a crown of gold for the border thereof round about.

- Matthew 19:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he answered and said unto them, Have ye not read, that he which made them at the beginning made them male and female,

- 2 Corinthians 5:21chapter context similar meaning copy save

- For he hath made him to be sin for us, who knew no sin; that we might be made the righteousness of God in him.

This is page: 1 of 44

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 3031 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 Next >

You searched for

"PRAYER" in the KJV Bible

107 Instances - Page 1 of 4 - Sort by Book Order - Feedback

- Psalms 102:17chapter context similar meaning copy save

- He will regard the prayer of the destitute, and not despise their prayer.

- Psalms 17:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- (A Prayer of David.) Hear the right, O LORD, attend unto my cry, give ear unto my prayer, that goeth not out of feigned lips.

- Psalms 102:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- (A Prayer of the afflicted, when he is overwhelmed, and poureth out his complaint before the LORD.) Hear my prayer, O LORD, and let my cry come unto thee.

- 2 Chronicles 6:19chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Have respect therefore to the prayer of thy servant, and to his supplication, O LORD my God, to hearken unto the cry and the prayer which thy servant prayeth before thee:

- 1 Kings 8:28chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Yet have thou respect unto the prayer of thy servant, and to his supplication, O LORD my God, to hearken unto the cry and to the prayer, which thy servant prayeth before thee to day:

- Isaiah 56:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Even them will I bring to my holy mountain, and make them joyful in my house of prayer: their burnt offerings and their sacrifices shall be accepted upon mine altar; for mine house shall be called an house of prayer for all people.

- Nehemiah 1:11chapter context similar meaning copy save

- O Lord, I beseech thee, let now thine ear be attentive to the prayer of thy servant, and to the prayer of thy servants, who desire to fear thy name: and prosper, I pray thee, thy servant this day, and grant him mercy in the sight of this man. For I was the king's cupbearer.

- Habakkuk 3:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- A prayer of Habakkuk the prophet upon Shigionoth.

- Romans 12:12chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Rejoicing in hope; patient in tribulation; continuing instant in prayer;

- 1 Timothy 4:5chapter context similar meaning copy save

- For it is sanctified by the word of God and prayer.

- Psalms 54:2chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Hear my prayer, O God; give ear to the words of my mouth.

- Lamentations 3:8chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Also when I cry and shout, he shutteth out my prayer.

- Colossians 4:2chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Continue in prayer, and watch in the same with thanksgiving;

- Job 16:17chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Not for any injustice in mine hands: also my prayer is pure.

- Psalms 109:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- For my love they are my adversaries: but I give myself unto prayer.

- Psalms 86:6chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Give ear, O LORD, unto my prayer; and attend to the voice of my supplications.

- Job 15:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Yea, thou castest off fear, and restrainest prayer before God.

- Psalms 88:2chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Let my prayer come before thee: incline thine ear unto my cry;

- Psalms 65:2chapter context similar meaning copy save

- O thou that hearest prayer, unto thee shall all flesh come.

- Matthew 17:21chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Howbeit this kind goeth not out but by prayer and fasting.

- Philippians 1:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Always in every prayer of mine for you all making request with joy,

- Psalms 66:20chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Blessed be God, which hath not turned away my prayer, nor his mercy from me.

- Psalms 86:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- (A Prayer of David.) Bow down thine ear, O LORD, hear me: for I am poor and needy.

- 1 Peter 4:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But the end of all things is at hand: be ye therefore sober, and watch unto prayer.

- Romans 10:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Brethren, my heart's desire and prayer to God for Israel is, that they might be saved.

- Psalms 80:4chapter context similar meaning copy save

- O LORD God of hosts, how long wilt thou be angry against the prayer of thy people?

- Psalms 61:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- (To the chief Musician upon Neginah, A Psalm of David.) Hear my cry, O God; attend unto my prayer.

- Lamentations 3:44chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Thou hast covered thyself with a cloud, that our prayer should not pass through.

- Psalms 90:1chapter context similar meaning copy save

- (A Prayer of Moses the man of God.) Lord, thou hast been our dwelling place in all generations.

- Jonah 2:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- When my soul fainted within me I remembered the LORD: and my prayer came in unto thee, into thine holy temple.

This is page: 1 of 4

1 2 3 4 Next >

You searched for

"FLOOR" in the KJV Bible

18 Instances - Page 1 of 1 - Sort by Book Order - Feedback

- 1 Kings 6:15chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he built the walls of the house within with boards of cedar, both the floor of the house, and the walls of the cieling: and he covered them on the inside with wood, and covered the floor of the house with planks of fir.

- 1 Kings 6:30chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And the floor of the house he overlaid with gold, within and without.

- Ruth 3:6chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And she went down unto the floor, and did according to all that her mother in law bade her.

- Isaiah 21:10chapter context similar meaning copy save

- O my threshing, and the corn of my floor: that which I have heard of the LORD of hosts, the God of Israel, have I declared unto you.

- Micah 4:12chapter context similar meaning copy save

- But they know not the thoughts of the LORD, neither understand they his counsel: for he shall gather them as the sheaves into the floor.

- 1 Kings 7:7chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Then he made a porch for the throne where he might judge, even the porch of judgment: and it was covered with cedar from one side of the floor to the other.

- 2 Chronicles 34:11chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Even to the artificers and builders gave they it, to buy hewn stone, and timber for couplings, and to floor the houses which the kings of Judah had destroyed.

- Hosea 9:2chapter context similar meaning copy save

- The floor and the winepress shall not feed them, and the new wine shall fail in her.

- Ruth 3:14chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And she lay at his feet until the morning: and she rose up before one could know another. And he said, Let it not be known that a woman came into the floor.

- Genesis 50:11chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And when the inhabitants of the land, the Canaanites, saw the mourning in the floorof Atad, they said, This is a grievous mourning to the Egyptians: wherefore the name of it was called Abelmizraim, which is beyond Jordan.

- Matthew 3:12chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Whose fan is in his hand, and he will throughly purge his floor, and gather his wheat into the garner; but he will burn up the chaff with unquenchable fire.

- Luke 3:17chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Whose fan is in his hand, and he will throughly purge his floor, and will gather the wheat into his garner; but the chaff he will burn with fire unquenchable.

- Hosea 13:3chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Therefore they shall be as the morning cloud, and as the early dew that passeth away, as the chaff that is driven with the whirlwind out of the floor, and as the smoke out of the chimney.

- Judges 6:37chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Behold, I will put a fleece of wool in the floor; and if the dew be on the fleece only, and it be dry upon all the earth beside, then shall I know that thou wilt save Israel by mine hand, as thou hast said.

- Ruth 3:3chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Wash thyself therefore, and anoint thee, and put thy raiment upon thee, and get thee down to the floor: but make not thyself known unto the man, until he shall have done eating and drinking.

- Deuteronomy 15:14chapter context similar meaning copy save

- Thou shalt furnish him liberally out of thy flock, and out of thy floor, and out of thy winepress: of that wherewith the LORD thy God hath blessed thee thou shalt give unto him.

- 1 Kings 6:16chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And he built twenty cubits on the sides of the house, both the floor and the walls with boards of cedar: he even built them for it within, even for the oracle, even for the most holy place.

- Numbers 5:17chapter context similar meaning copy save

- And the priest shall take holy water in an earthen vessel; and of the dust that is in the floor of the tabernacle the priest shall take, and put it into the water:

Approximations of π

| Part of a series of articles on the |

| mathematical constant π |

|---|

| 3.1415926535897932384626433... |

| Uses |

| Properties |

| Value |

| People |

| History |

| In culture |

| Related topics |

Approximations for the mathematical constant pi (π) in the history of mathematics reached an accuracy within 0.04% of the true value before the beginning of the Common Era. In Chinese mathematics, this was improved to approximations correct to what corresponds to about seven decimal digits by the 5th century.

Further progress was not made until the 14th century, when Madhava of Sangamagrama developed approximations correct to eleven and then thirteen digits. Jamshīd al-Kāshī achieved sixteen digits next. Early modern mathematicians reached an accuracy of 35 digits by the beginning of the 17th century (Ludolph van Ceulen), and 126 digits by the 19th century (Jurij Vega).

The record of manual approximation of π is held by William Shanks, who calculated 527 decimals correctly in 1853.[1] Since the middle of the 20th century, the approximation of π has been the task of electronic digital computers (for a comprehensive account, see Chronology of computation of π). On April 2, 2025, the current record was established by Linus Media Group and Kioxia with Alexander Yee's y-cruncher with 300 trillion (3×1014) digits.[2]

Early history

[edit]The best known approximations to π dating to before the Common Era were accurate to two decimal places; this was improved upon in Chinese mathematics in particular by the mid-first millennium, to an accuracy of seven decimal places. After this, no further progress was made until the late medieval period.

Some Egyptologists[3] have claimed that the ancient Egyptians used an approximation of π as 22⁄7 = 3.142857 (about 0.04% too high) from as early as the Old Kingdom (c. 2700–2200 BC).[4] This claim has been met with skepticism.[5][6]

Babylonian mathematics usually approximated π to 3, sufficient for the architectural projects of the time (notably also reflected in the description of Solomon's Temple in the Hebrew Bible).[7] The Babylonians were aware that this was an approximation, and one Old Babylonian mathematical tablet excavated near Susa in 1936 (dated to between the 19th and 17th centuries BCE) gives a better approximation of π as 25⁄8 = 3.125, about 0.528% below the exact value.[8][9][10][11]

At about the same time, the Egyptian Rhind Mathematical Papyrus (dated to the Second Intermediate Period, c. 1600 BCE, although stated to be a copy of an older, Middle Kingdom text) implies an approximation of π as 256⁄81 ≈ 3.16 (accurate to 0.6 percent) by calculating the area of a circle via approximation with the octagon.[5][12]

Astronomical calculations in the Shatapatha Brahmana (c. 6th century BCE) use a fractional approximation of 339⁄108 ≈ 3.139.[13]

The Mahabharata (500 BCE – 300 CE) offers an approximation of 3, in the ratios offered in Bhishma Parva verses: 6.12.40–45.[14]

— "verses: 6.12.40–45, Bhishma Parva of the Mahabharata"

In the 3rd century BCE, Archimedes proved the sharp inequalities 223⁄71 < π < 22⁄7, by means of regular 96-gons (accuracies of 2·10−4and 4·10−4, respectively).[15]

In the 2nd century CE, Ptolemy used the value 377⁄120, the first known approximation accurate to three decimal places (accuracy 2·10−5).[16] It is equal to which is accurate to two sexagesimal digits.

The Chinese mathematician Liu Hui in 263 CE computed π to between 3.141024 and 3.142708 by inscribing a 96-gon and 192-gon; the average of these two values is 3.141866 (accuracy 9·10−5). He also suggested that 3.14 was a good enough approximation for practical purposes. He has also frequently been credited with a later and more accurate result, π ≈ 3927⁄1250 = 3.1416 (accuracy 2·10−6), although some scholars instead believe that this is due to the later (5th-century) Chinese mathematician Zu Chongzhi.[17] Zu Chongzhi is known to have computed π to be between 3.1415926 and 3.1415927, which was correct to seven decimal places. He also gave two other approximations of π: π ≈ 22⁄7 and π ≈ 355⁄113, which are not as accurate as his decimal result. The latter fraction is the best possible rational approximation of π using fewer than five decimal digits in the numerator and denominator. Zu Chongzhi's results surpass the accuracy reached in Hellenistic mathematics, and would remain without improvement for close to a millennium.

In Gupta-era India (6th century), mathematician Aryabhata, in his astronomical treatise Āryabhaṭīya stated:

Approximating π to four decimal places: π ≈ 62832⁄20000 = 3.1416,[18][19][20] Aryabhata stated that his result "approximately" (āsanna"approaching") gave the circumference of a circle. His 15th-century commentator Nilakantha Somayaji (Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics) has argued that the word means not only that this is an approximation, but that the value is incommensurable (irrational).[21]

Middle Ages

[edit]Further progress was not made for nearly a millennium, until the 14th century, when Indian mathematician and astronomer Madhava of Sangamagrama, founder of the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics, found the Maclaurin series for arctangent, and then two infinite series for π.[22][23][24] One of them is now known as the Madhava–Leibniz series, based on

The other was based on

He used the first 21 terms to compute an approximation of π correct to 11 decimal places as 3.14159265359.

He also improved the formula based on arctan(1) by including a correction:

It is not known how he came up with this correction.[23] Using this he found an approximation of π to 13 decimal places of accuracy when n = 75.

Indian mathematician Bhaskara II used regular polygons with up to 384 sides to obtain a close approximation of π, calculating it as 3.141666.[25]

Jamshīd al-Kāshī (Kāshānī), a Persian astronomer and mathematician, correctly computed the fractional part of 2π to 9 sexagesimal digits in 1424,[26] and translated this into 16 decimal digits[27] after the decimal point:

which gives 16 correct digits for π after the decimal point:

He achieved this level of accuracy by calculating the perimeter of a regular polygon with 3 × 228 sides.[28]

16th to 19th centuries

[edit]In the second half of the 16th century, the French mathematician François Viète discovered an infinite product that converged on πknown as Viète's formula.

The German-Dutch mathematician Ludolph van Ceulen (circa 1600) computed the first 35 decimal places of π with a 262-gon. He was so proud of this accomplishment that he had them inscribed on his tombstone.[29]

In Cyclometricus (1621), Willebrord Snellius demonstrated that the perimeter of the inscribed polygon converges on the circumference twice as fast as does the perimeter of the corresponding circumscribed polygon. This was proved by Christiaan Huygens in 1654. Snellius was able to obtain seven digits of π from a 96-sided polygon.[30]

In 1656, John Wallis published the Wallis product:

In 1706, John Machin used Gregory's series (the Taylor series for arctangent) and the identity to calculate 100 digits of π (see § Machin-like formula below).[31][32] In 1719, Thomas de Lagny used a similar identity to calculate 127 digits (of which 112 were correct). In 1789, the Slovene mathematician Jurij Vega improved John Machin's formula to calculate the first 140 digits, of which the first 126 were correct.[33] In 1841, William Rutherford calculated 208 digits, of which the first 152 were correct.

The magnitude of such precision (152 decimal places) can be put into context by the fact that the circumference of the largest known object, the observable universe, can be calculated from its diameter (93 billion light-years) to a precision of less than one Planck length (at 1.6162×10−35 meters, the shortest unit of length expected to be directly measurable) using π expressed to just 62 decimal places.[34]

The English amateur mathematician William Shanks calculated π to 530 decimal places in January 1853, of which the first 527 were correct (the last few likely being incorrect due to round-off errors).[1][35] He subsequently expanded his calculation to 607 decimal places in April 1853,[36] but an error introduced right at the 530th decimal place rendered the rest of his calculation erroneous; due to the nature of Machin's formula, the error propagated back to the 528th decimal place, leaving only the first 527 digits correct once again.[1] Twenty years later, Shanks expanded his calculation to 707 decimal places in April 1873.[37] Due to this being an expansion of his previous calculation, most of the new digits were incorrect as well.[1] Shanks was said to have calculated new digits all morning and would then spend all afternoon checking his morning's work. This was the longest expansion of π until the advent of the electronic digital computer three-quarters of a century later.[38]

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]In 1910, the Indian mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan found several rapidly converging infinite series of π, including

which computes a further eight decimal places of π with each term in the series. His series are now the basis for the fastest algorithms currently used to calculate π. Evaluating the first term alone yields a value correct to seven decimal places:

From the mid-20th century onwards, all improvements in calculation of π have been done with the help of calculators or computers.

In 1944−45, D. F. Ferguson, with the aid of a mechanical desk calculator, found that William Shanks had made a mistake in the 528th decimal place, and that all succeeding digits were incorrect.[35][39]

In the early years of the computer, an expansion of π to 100000 decimal places[40]: 78 was computed by Maryland mathematician Daniel Shanks (no relation to the aforementioned William Shanks) and his team at the United States Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C. In 1961, Shanks and his team used two different power series for calculating the digits of π. For one, it was known that any error would produce a value slightly high, and for the other, it was known that any error would produce a value slightly low. And hence, as long as the two series produced the same digits, there was a very high confidence that they were correct. The first 100,265 digits of π were published in 1962.[40]: 80–99 The authors outlined what would be needed to calculate π to 1 million decimal places and concluded that the task was beyond that day's technology, but would be possible in five to seven years.[40]: 78

In 1989, the Chudnovsky brothers computed π to over 1 billion decimal places on the supercomputer IBM 3090 using the following variation of Ramanujan's infinite series of π:

Records since then have all been accomplished using the Chudnovsky algorithm. In 1999, Yasumasa Kanada and his team at the University of Tokyo computed π to over 200 billion decimal places on the supercomputer HITACHI SR8000/MPP (128 nodes) using another variation of Ramanujan's infinite series of π. In November 2002, Yasumasa Kanada and a team of 9 others used the Hitachi SR8000, a 64-node supercomputer with 1 terabyte of main memory, to calculate π to roughly 1.24 trillion digits in around 600 hours (25 days).[41]

Recent records

[edit]- In August 2009, a Japanese supercomputer called the T2K Open Supercomputer more than doubled the previous record by calculating π to roughly 2.6 trillion digits in approximately 73 hours and 36 minutes.

- In December 2009, Fabrice Bellard used a home computer to compute 2.7 trillion decimal digits of π. Calculations were performed in base 2 (binary), then the result was converted to base 10 (decimal). The calculation, conversion, and verification steps took a total of 131 days.[42]

- In August 2010, Shigeru Kondo used Alexander Yee's y-cruncher to calculate 5 trillion digits of π. This was the world record for any type of calculation, but significantly it was performed on a home computer built by Kondo.[43] The calculation was done between 4 May and 3 August, with the primary and secondary verifications taking 64 and 66 hours respectively.[44]

- In October 2011, Shigeru Kondo broke his own record by computing ten trillion (1013) and fifty digits using the same method but with better hardware.[45][46]

- In December 2013, Kondo broke his own record for a second time when he computed 12.1 trillion digits of π.[47]

- In October 2014, Sandon Van Ness, going by the pseudonym "houkouonchi" used y-cruncher to calculate 13.3 trillion digits of π.[48]

- In November 2016, Peter Trueb and his sponsors computed on y-cruncher and fully verified 22.4 trillion digits of π(22,459,157,718,361 (πe × 1012)).[49] The computation took (with three interruptions) 105 days to complete,[48] the limitation of further expansion being primarily storage space.[47]

- In March 2019, Emma Haruka Iwao, an employee at Google, computed 31.4 (approximately 10π) trillion digits of pi using y-cruncher and Google Cloud machines. This took 121 days to complete.[50]

- In January 2020, Timothy Mullican announced the computation of 50 trillion digits over 303 days.[51][52]

- On 14 August 2021, a team (DAViS) at the University of Applied Sciences of the Grisons announced completion of the computation of π to 62.8 (approximately 20π) trillion digits.[53][54]

- On 8 June 2022, Emma Haruka Iwao announced on the Google Cloud Blog the computation of 100 trillion (1014) digits of πover 158 days using Alexander Yee's y-cruncher.[55]

- On 14 March 2024, Jordan Ranous, Kevin O’Brien and Brian Beeler computed π to 105 trillion digits, also using y-cruncher.[56]

- On 28 June 2024, the StorageReview Team computed π to 202 trillion digits, also using y-cruncher.[57]

- On 2 April 2025, Linus Media Group and Kioxia computed π to 300 trillion digits, also using y-cruncher.[2]

Practical approximations

[edit]Depending on the purpose of a calculation, π can be approximated by using fractions for ease of calculation. The most notable such approximations are 22⁄7 (relative error of about 4·10−4) and 355⁄113 (relative error of about 8·10−8).[58][59][60] In Chinese mathematics, the fractions 22/7 and 355/113 are known as Yuelü (约率; yuēlǜ; 'approximate ratio') and Milü (密率; mìlǜ; 'close ratio').

Non-mathematical "definitions" of π

[edit]Of some notability are legal or historical texts purportedly "defining π" to have some rational value, such as the "Indiana Pi Bill" of 1897, which stated "the ratio of the diameter and circumference is as five-fourths to four" (which would imply "π = 3.2") and a passage in the Hebrew Bible that implies that π = 3.

Indiana bill

[edit]The so-called "Indiana Pi Bill" from 1897 has often been characterized as an attempt to "legislate the value of Pi". Rather, the bill dealt with a purported solution to the problem of geometrically "squaring the circle".[61]

The bill was nearly passed by the Indiana General Assembly in the U.S., and has been claimed to imply a number of different values for π, although the closest it comes to explicitly asserting one is the wording "the ratio of the diameter and circumference is as five-fourths to four", which would make π = 16⁄5 = 3.2, a discrepancy of nearly 2 percent. A mathematics professor who happened to be present the day the bill was brought up for consideration in the Senate, after it had passed in the House, helped to stop the passage of the bill on its second reading, after which the assembly thoroughly ridiculed it before postponing it indefinitely.

Imputed biblical value