The correlation of Cantore Arithmetic must harness the carriage of Albert Einstein at basic works. The aspect of ‘relativity’ is found through the verse, “a picture is worth a thousand words”. To understand the comprehension is to comprehend the advertisement through the work of the glyph and this is not a pixel. To further the advancement of Cantore Arithmetic the glyph will perform to the importance of the King James Version to the advancement of relation to the number three.

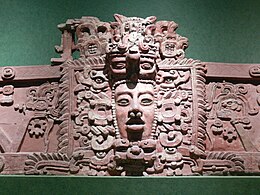

Psalms 106:19: They made a calf in Horeb and worshipped the motion image. The bar has no rose as the Aztec and the Mayan places: Marduk (Cuneiform: 𒀭𒀫𒌓 dAMAR.UTU; Sumerian: amar utu.k "calf of the sun; solar calf"; Hebrew: מְרֹדַךְ, Modern: Mərōdaḵ, Tiberian: Merōḏaḵ) was a god from ancient Mesopotamia and patron deity of the city of Babylon. When Babylon became the political center of the Euphrates valley in the time of Hammurabi(18th century BC), Marduk slowly started to rise to the position of the head of the Babylonian pantheon, a position he fully acquired by the second half of the second millennium [2] BC. In the city of Babylon, Marduk was worshipped in the temple Esagila. Marduk is associated with the divine weapon Imhullu. His symbolic animal and servant, whom Marduk once vanquished, is the dragon Mušḫuššu.[3] "Marduk" is the Babylonianform of his name.[4]

By the Hammurabi period, Marduk had become astrologically associated with the planet Jupiter.[7]

To encounter the basis at the written and the glyph to what is the pixel will increase the verse to the science of computation.

Anunnaki

The Anunnaki (Sumerian: 𒀭𒀀𒉣𒈾, also transcribed as Anunaki, Annunaki, Anunna, Ananakiand other variations) are a group of deities of the ancient Sumerians, Akkadians, Assyrians and Babylonians.[1] In the earliest Sumerian writings about them, which come from the Post-Akkadian period, the Anunnaki are deities in the pantheon, descendants of An and Ki, the god of the heavens and the goddess of earth, and their primary function was to decree the fates of humanity.

Etymology[edit]

The name Anunnaki is derived from An,[2] the Sumerian god of the sky.[2] The name is variously written "da-nuna", "da-nuna-ke4-ne", or "da-nun-na", meaning "princely offspring" or "offspring of An".[1]

The Anunnaki were believed to be the offspring of An and his consort, the earth goddess Ki.[1] Samuel Noah Kramer identifies Ki with the Sumerian mother goddess Ninhursag, stating that they were originally the same figure.[3][4] The oldest of the Anunnaki was Enlil, the god of air[5] and chief god of the Sumerian pantheon.[6] The Sumerians believed that, until Enlil was born, heaven and earth were inseparable.[7] Then, Enlil cleft heaven and earth in two[7] and carried away the earth[8] while his father An carried away the sky.[8]

Worship and iconography[edit]

The Anunnaki are chiefly mentioned in literary texts[9] and very little evidence to support the existence of any cult of them has yet been unearthed.[9][10] This is likely due to the fact that each member of the Anunnaki had his or her own individual cult, separate from the others.[11] Similarly, no representations of the Anunnaki as a complete group have yet been discovered,[11] although a few depictions of two or three individual members together have been identified.[11] Deities in ancient Mesopotamia were almost exclusively anthropomorphic.[12] They were thought to possess extraordinary powers[12] and were often envisioned as being of tremendous physical size.[12] The deities typically wore melam, an ambiguous substance which "covered them in terrifying splendor".[13] Melam could also be worn by heroes, kings, giants, and even demons.[14] The effect that seeing a deity's melam has on a human is described as ni, a word for the physical tingling of the flesh.[15] Deities were almost always depicted wearing horned caps,[16][17] consisting of up to seven superimposed pairs of ox-horns.[18] They were also sometimes depicted wearing clothes with elaborate decorative gold and silver ornaments sewn into them.[17]

The ancient Mesopotamians believed that their deities lived in Heaven,[19] after an earlier history of visiting earth in the mythological texts, and that a god's statue was a physical embodiment of the god himself.[19][20] As such, cult statues were given constant care and attention[19][21] and a set of priests was assigned to tend to them.[22] These priests would clothe the statues[20] and place feasts before them so they could "eat".[19][21] A deity's temple was believed to be that deity's literal place of residence.[23] The gods had boats, full-sized barges which were normally stored inside their temples[24] and were used to transport their cult statues along waterways during various religious festivals.[24] The gods also had chariots, which were used for transporting their cult statues by land.[25] Sometimes a deity's cult statue would be transported to the location of a battle so that the deity could watch the battle unfold.[25]The major deities of the Mesopotamian pantheon, which included the Anunnaki, were believed to participate in the "assembly of the gods",[16] through which the gods made all of their decisions.[16] This assembly was seen as a divine counterpart to the semi-democratic legislative system that existed during the Third Dynasty of Ur (c. 2112 BC–c. 2004 BC).[16]

Mythology[edit]

Sumerian[edit]

The earliest known usages of the term Anunnaki come from inscriptions written during the reign of Gudea (c. 2144–2124 BC) and the Third Dynasty of Ur.[9][11] In the earliest texts, the term is applied to the most powerful and important deities in the Sumerian pantheon: the descendants of the sky-god An.[9][26]This group of deities probably included the "seven gods who decree":[27] An, Enlil, Enki, Ninhursag, Nanna, Utu, and Inanna.[28]

Although certain deities are described as members of the Anunnaki, no complete list of the names of all the Anunnaki has survived[11] and they are usually only referred to as a cohesive group in literary texts.[9][11] Furthermore, Sumerian texts describe the Anunnaki inconsistently[11] and do not agree on how many Anunnaki there were, or what their divine function was.[9][11] Originally, the Anunnaki appear to have been heavenly deities with immense powers.[11] In the poem Enki and the World Order, the Anunnaki "do homage" to Enki, sing hymns of praise in his honor, and "take up their dwellings" among the people of Sumer.[9][29] The same composition twice states that the Anunnaki "decree the fates of mankind".[9]

Virtually every major deity in the Sumerian pantheon was regarded as the patron of a specific city[30] and was expected to protect that city's interests.[30]The deity was believed to permanently reside within that city's temple.[31] One text mentions as many as fifty Anunnaki associated with the city of Eridu.[1][32] In Inanna's Descent into the Netherworld, there are only seven Anunnaki, who reside within the Underworld and serve as judges.[9][33] Inannastands trial before them for her attempt to take over the Underworld;[9][33] they deem her guilty of hubris and condemn her to death.[33]

Major deities in Sumerian mythology were associated with specific celestial bodies.[34] Inanna was believed to be the planet Venus.[35][36] Utu was believed to be the sun.[36][37] Nanna was the moon.[36][38] An was identified with all the stars of the equatorial sky, Enlil with those of the northern sky, and Enki with those of the southern sky.[39] The path of Enlil's celestial orbit was a continuous, symmetrical circle around the north celestial pole,[40] but those of An and Enki were believed to intersect at various points.[41]

Akkadian, Babylonian and Assyrian[edit]

Akkadian texts of the second millennium BC follow similar portrayals of the Anunnaki from Inanna's Descent into the Netherworld, depicting them as chthonic Underworld deities. In an abbreviated Akkadian version of Inanna's Descent written in the early second millennium, Ereshkigal, the queen of the Underworld, comments that she "drink[s] water with the Anunnaki".[43] Later in the same poem, Ereshkigal orders her servant Namtar to fetch the Anunnaki from Egalgina,[44] to "decorate the threshold steps with coral",[44] and to "seat them on golden thrones".[44]

During the Old Babylonian Period (c. 1830 BC – c. 1531 BC), a new set of deities known as the Igigi are introduced.[45] The relationship between the Anunnaki and the Igigi is unclear.[11] On some occasions, the categories appear to be used synonymously,[9][11] but in other writings, such as The Poem of Erra, there is a clear distinction between the two.[9][11] In the late Akkadian Atra-Hasis epic, the Igigi are the sixth generation of the gods who are forced to perform labor for the Anunnaki.[46][47] After forty days, the Igigi rebel and the god Enki, one of the Anunnaki, creates humans to replace them.[46][47]

From the Middle Babylonian Period (c. 1592 – 1155 BC) onward, the name Anunnaki was applied generally to the deities of the underworld;[1] whereas the name Igigi was applied to the heavenly deities.[1] During this period, the underworld deities Damkina, Nergal, and Madānu are listed as the most powerful among the Anunnaki,[1]alongside Marduk, the national god of ancient Babylon.[1]

In the standard Akkadian Epic of Gilgamesh (c. 1200 BC) Utnapishtim, the immortal survivor of the Great Flood, describes the Anunnaki as seven judges of the Underworld, who set the land aflame as the storm approaches.[48]Later, when the flood comes, Ishtar (the East Semitic equivalent to Inanna) and the Anunnaki mourn over the destruction of humanity.[9][49]

In the Babylonian Enûma Eliš, Marduk assigns the Anunnaki their positions.[50] A late Babylonian version of the epic mentions 600 Anunnaki of the underworld,[1] but only 300 Anunnaki of heaven,[1] indicating the existence of a complex underworld cosmology.[1] In gratitude, the Anunnaki, the "Great Gods", build Esagila, a "splendid" temple dedicated to Marduk, Ea, and Ellil.[51] In the eighth-century BC Poem of Erra, the Anunnaki are described as the brothers of the god Nergal[9] and are depicted as antagonistic towards humanity.[9]

A badly damaged text from the Neo-Assyrian Period (911 – 612 BC) describes Marduk leading his army of Anunnaki into the sacred city of Nippur and causing a disturbance.[52] The disturbance causes a flood,[52] which forces the resident gods of Nippur to take shelter in the Eshumesha temple to Ninurta.[52] Enlil is enraged at Marduk's transgression and orders the gods of Eshumesha to take Marduk and the other Anunnaki as prisoners.[52] The Anunnaki are captured,[52] but Marduk appoints his front-runner Mushteshirhablim to lead a revolt against the gods of Eshumesha[53] and sends his messenger Neretagmil to alert Nabu, the god of literacy.[53] When the Eshumesha gods hear Nabu speak, they come out of their temple to search for him.[54] Marduk defeats the Eshumesha gods and takes 360 of them as prisoners of war, including Enlil himself.[54] Enlil protests that the Eshumesha gods are innocent,[54] so Marduk puts them on trial before the Anunnaki.[54] The text ends with a warning from Damkianna (another name for Ninhursag) to the gods and to humanity, pleading them not to repeat the war between the Anunnaki and the gods of Eshumesha.[54]

Hurrian and Hittite[edit]

In the mythologies of the Hurrians and Hittites (which flourished in the mid to late second millennium BC), the oldest generation of gods was believed to have been banished by the younger gods to the Underworld,[56][58] where they were ruled by the goddess Lelwani.[58] Hittite scribes identified these deities with the Anunnaki.[56][57] In ancient Hurrian, the Anunnaki are referred to as karuileš šiuneš, which means "former ancient gods",[59] or kattereš šiuneš, which means "gods of the earth".[59] Hittite and Hurrian treaties were often sworn by the old gods in order to ensure that the oaths would be kept.[56][59] In one myth, the gods are threatened by the stone giant Ullikummi,[60] so Ea (the later name for Enki) commands the Former Gods to find the weapon that was used to separate the heavens from the earth.[56][61] They find it and use it to cut off Ullikummi's feet.[61]

Although the names of the Anunnaki in Hurrian and Hittite texts frequently vary,[57] they are always eight in number.[57] In one Hittite ritual, the names of the old gods are listed as: "Aduntarri the diviner, Zulki the dream interpretess, Irpitia Lord of the Earth, Narā, Namšarā, Minki, Amunki, and Āpi."[57] The old gods had no identifiable cult in the Hurrio-Hittite religion;[57] instead, the Hurrians and Hittites sought to communicate with the old gods through the ritual sacrifice of a piglet in a pit dug in the ground.[62] The old gods were often invoked to perform ritual purifications.[63]

The Hittite account of the old gods' banishment to the Underworld is closely related with the Greek poet Hesiod's narrative of the overthrow of the Titans by the Olympians in his Theogony.[64] The Greek sky-god Ouranos (whose name means "Heaven") is the father of the Titans[65] and is derived from the Hittite version of Anu.[66] In Hesiod's account, Ouranos is castrated by his son Cronus,[67] just as Anu was castrated by his son Kumarbi in the Hittite story.[68]

Pseudoarchaeology and conspiracy theories[edit]

Over a series of published books (starting with Chariots of the Gods? in 1968), pseudoarcheologist Erich von Däniken claimed that extraterrestrial "ancient astronauts" had visited a prehistoric Earth. Däniken explains the origins of religions as reactions to contact with an alien race, and offers interpretations of Sumerian texts and the Old Testament as evidence.[69][70][71]

In his 1976 book The Twelfth Planet, author Zecharia Sitchin claimed that the Anunnaki were actually an advanced humanoid extraterrestrial species from the undiscovered planet Nibiru, who came to Earth around 500,000 years ago and constructed a base of operations in order to mine gold after discovering that the planet was rich in the precious metal.[69][70][72] According to Sitchin, the Anunnaki hybridized their species and Homo erectus via in vitro fertilizationin order to create humans as a slave species of miners.[69][70][72] Sitchin claimed that the Anunnaki were forced to temporarily leave Earth's surface and orbit the planet when Antarctic glaciers melted, causing the Great Flood,[73] which also destroyed the Anunnaki's bases on Earth.[73] These had to be rebuilt, and the Anunnaki, needing more humans to help in this massive effort, taught mankind agriculture.[73]

Ronald H. Fritze writes that, according to Sitchin, "the Annunaki built the pyramids and all the other monumental structures from around the ancient world that ancient astronaut theorists consider so impossible to build without highly advanced technologies."[69] Sitchin expanded on this mythology in later works, including The Stairway to Heaven (1980) and The Wars of Gods and Men (1985).[74] In The End of Days: Armageddon and the Prophecy of the Return (2007), Sitchin predicted that the Anunnaki would return to earth, possibly as soon as 2012, corresponding to the end of the Mesoamerican Long Count calendar.[70][74] Sitchin's writings have been universally rejected by mainstream historians, who have labelled his books as pseudoarchaeology,[75]asserting that Sitchin seems to deliberately misrepresent Sumerian texts by quoting them out of context, truncating quotations, and mistranslating Sumerian words to give them radically different meanings from their accepted definitions.[76]

David Icke, the British conspiracy theorist who popularised the reptilian conspiracy theory, has claimed that the reptilian overlords of his theory are in fact the Anunnaki. Clearly influenced by Sitchin's writings, Icke adapts them "in favor of his own New Age and conspiratorial agenda".[77] Icke's speculation on the Anunnaki incorporates far-right views on history, positing an Aryan master race descended by blood from the Anunnaki.[78] It also incorporates dragons, Dracula, and draconian laws,[79] these three elements apparently linked only by superficial linguistic similarity. He formulated his views on the Anunnaki in the 1990s and has written several books about his theory.[80] In his 2001 documentary about Icke, Jon Ronson cited a cartoon, "Rothschild" (1898), by Charles Léandre, arguing that Jews have long been depicted as lizard-like creatures who are out to control the world.

Maya script

| Maya script | |

|---|---|

Pages 6, 7, and 8 of the Dresden Codex, showing letters, numbers, and the images that often accompany Maya writing | |

| Script type | |

Time period | 3rd century BCE to 16th century CE |

| Direction | mixed |

| Languages | Mayan languages |

| ISO 15924 | |

| ISO 15924 | Maya (090), Mayan hieroglyphs |

| Unicode | |

| None (tentative range U+15500–U+159FF) | |

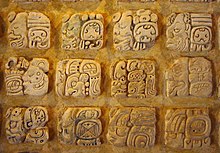

Maya script, also known as Maya glyphs, is historically the native writing system of the Maya civilization of Mesoamerica and is the only Mesoamerican writing system that has been substantially deciphered. The earliest inscriptions found which are identifiably Maya date to the 3rd century BCE in San Bartolo, Guatemala.[1][2] Maya writing was in continuous use throughout Mesoamerica until the Spanish conquest of the Maya in the 16th and 17th centuries.

Maya writing used logograms complemented with a set of syllabic glyphs, somewhat similar in function to modern Japanese writing. Maya writing was called "hieroglyphics" or hieroglyphs by early European explorers of the 18th and 19th centuries who found its general appearance reminiscent of Egyptian hieroglyphs, although the two systems are unrelated.

Though modern Mayan languages are almost entirely written using the Latin alphabet rather than Maya script,[3] there have been recent developments encouraging a revival of the Maya glyph system.

Languages[edit]

Evidence suggests that codices and other classic texts were written by scribes—usually members of the Maya priesthood—in Classic Maya, a literary form of the extinct Chʼoltiʼ language.[4][5] It is possible that the Maya elite spoke this language as a lingua franca over the entire Maya-speaking area, but texts were also written in other Mayan languages of the Petén and Yucatán, especially Yucatec. There is also some evidence that the script may have been occasionally used to write Mayan languages of the Guatemalan Highlands.[5]However, if other languages were written, they may have been written by Chʼoltiʼ scribes, and therefore have Chʼoltiʼ elements.

Structure[edit]

Mayan writing consisted of a relatively elaborate set of glyphs, which were laboriously painted on ceramics, walls and bark-paper codices, carved in wood or stone, and molded in stucco. Carved and molded glyphs were painted, but the paint has rarely survived. As of 2008, the sound of about 80% of Maya writing could be read and the meaning of about 60% could be understood with varying degrees of certainty, enough to give a comprehensive idea of its structure.[6]

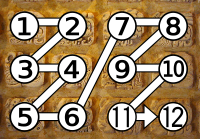

Maya texts were usually written in blocks arranged in columns two blocks wide, with each block corresponding to a noun or verb phrase. The blocks within the columns were read left to right, top to bottom, and would be repeated until there were no more columns left. Within a block, glyphs were arranged top-to-bottom and left-to-right (similar to Korean Hangul syllabic blocks). Glyphs were sometimes conflated into ligatures, where an element of one glyph would replace part of a second. In place of the standard block configuration, Maya was also sometimes written in a single row or column, or in an 'L' or 'T' shape. These variations most often appeared when they would better fit the surface being inscribed.

The Maya script was a logosyllabic system with some syllabogrammatic elements. Individual glyphs or symbols could represent either a morpheme or a syllable, and the same glyph could often be used for both. Because of these dual readings, it is customary to write logographic readings in all caps and phonetic readings in italics or bold. For example, a calendaric glyph can be read as the morpheme manikʼ or as the syllable chi.

Glyphs used as syllabograms were originally logograms for single-syllable words, usually those that ended in a vowel or in a weak consonant such as y, w, h, or glottal stop. For example, the logogram for 'fish fin'—found in two forms, as a fish fin and as a fish with prominent fins—was read as [kah] and came to represent the syllable ka. These syllabic glyphs performed two primary functions: as phonetic complements to disambiguate logograms which had more than one reading (similar to ancient Egyptian and modern Japanese furigana); and to write grammatical elements such as verbal inflections which did not have dedicated logograms (similar to Japanese okurigana). For example, bʼalam 'jaguar' could be written as a single logogram, bʼalam; a logogram with syllable additions, as ba-bʼalam, or bʼalam-ma, or bʼa-bʼalam-ma; or written completely phonetically with syllabograms as bʼa-la-ma.

In addition, some syllable glyphs were homophones, such as the six different glyphs used to write the very common third person pronoun u-.

Harmonic and disharmonic echo vowels[edit]

Phonetic glyphs stood for simple consonant-vowel (CV) or vowel-only (V) syllables. However, Mayan phonotactics is slightly more complicated than this. Most Mayan words end with consonants, and there may be sequences of two consonants within a word as well, as in xolteʼ ([ʃolteʔ] 'scepter') which is CVCCVC. When these final consonants were sonorants (l, m, n) or gutturals (j, h, ʼ) they were sometimes ignored ("underspelled"). More often, final consonants were written, which meant that an extra vowel was written as well. This was typically an "echo" vowelthat repeated the vowel of the previous syllable. For example, the word [kah] 'fish fin' would be underspelled ka or written in full as ka-ha. However, there are many cases where some other vowel was used, and the orthographic rules for this are only partially understood; this is largely due to the difficulty in ascertaining whether this vowel may be due to an underspelled suffix.

Lacadena & Wichmann (2004) proposed the following conventions:

- A CVC syllable was written CV-CV, where the two vowels (V) were the same: yo-po [yop] 'leaf'

- A syllable with a long vowel (CVVC) was written CV-Ci, unless the long vowel was [i], in which case it was written CiCa: ba-ki [baak] 'captive', yi-tzi-na [yihtziin] 'younger brother'

- A syllable with a glottalized vowel (CVʼC or CVʼVC) was written with a final a if the vowel was [e, o, u], or with a final u if the vowel was [a] or [i]: hu-na [huʼn] 'paper', ba-tzʼu [baʼtsʼ] 'howler monkey'.

- Preconsonantal [h] is not indicated.

In short, if the vowels are the same (harmonic), a simple vowel is intended. If the vowels are not the same (disharmonic), either two syllables are intended (likely underspelled), or else a single syllable with a long vowel (if V1 = [a e? o u] and V2 = [i], or else if V1 = [i] and V2 = [a]) or with a glottalized vowel (if V1 = [e? o u] and V2 = [a], or else if V1 = [a i] and V2 = [u]). The long-vowel reading of [Ce-Ci] is still uncertain, and there is a possibility that [Ce-Cu] represents a glottalized vowel (if it is not simply an underspelling for [CeCuC]), so it may be that the disharmonies form natural classes: [i] for long non-front vowels, otherwise [a] to keep it disharmonic; [u] for glottalized non-back vowels, otherwise [a].

A more complex spelling is ha-o-bo ko-ko-no-ma for [haʼoʼb kohknoʼm] 'they are the guardians'.[a] A minimal set is,

- ba-ka [bak]

- ba-ki [baak]

- ba-ku [baʼk] = [baʼak]

- ba-ke [baakel] (underspelled)

- ba-ke-le [baakel]

Verbal inflections[edit]

Despite depending on consonants which were frequently not written, the Mayan voice system was reliably indicated. For instance, the paradigm for a transitive verb with a CVC root is as follows:[7]

| Voice | Transliteration | Transcription | Gloss |

|---|---|---|---|

| Active | u-tzutz-wa | utzutzuw | "(s)he finished it" |

| Passive | tzutz-tza-ja | tzu[h]tzaj | "it was finished" |

| Mediopassive | tzutz-yi | tzutzuy | "it got finished" |

| Antipassive | tzutz-wi | tzutzuw | "(s)he finished" |

| Participial | tzutz-li | tzutzul | "finished" |

The active suffix did not participate in the harmonic/disharmonic system seen in roots, but rather was always -wa.

However, the language changed over 1500 years, and there were dialectal differences as well, which are reflected in the script, as seen next for the verb "(s)he sat" (⟨h⟩ is an infix in the root chum for the passive voice):[8]

| Period | Transliteration | Transcription |

|---|---|---|

| Late Preclassic | chum? | chu[h]m? |

| Early Classic | chum-ja | chu[h]m-aj |

| Classic (Eastern Chʼolan) | chum[mu]la-ja | chum-l-aj |

| Late Classic (Western Chʼolan) | chum[mu]wa-ni | chum-waan |

Emblem glyphs[edit]

An "emblem glyph" is a kind of royal title. It consists of a place name followed by the word ajaw, a Classic Maya term for "lord" with an unclear but well-attested etymology.[9] Sometimes the title is introduced by an adjective kʼuhul ("holy, divine" or "sacred"), resulting in the construction "holy [placename] lord". However, an "emblem glyph" is not a "glyph" at all: it can be spelled with any number of syllabic or logographic signs and several alternative spellings are attested for the words kʼuhul and ajaw, which form the stable core of the title. "Emblem glyph" simply reflects the time when Mayanists could not read Classic Maya inscriptions and used a term to isolate specific recurring structural components of the written narratives, and other remaining examples of Maya orthography.

This title was identified in 1958 by Heinrich Berlin, who coined the term "emblem glyph".[10] Berlin noticed that the "emblem glyphs" consisted of a larger "main sign" and two smaller signs now read as kʼuhul ajaw. Berlin also noticed that while the smaller elements remained relatively constant, the main sign changed from site to site. Berlin proposed that the main signs identified individual cities, their ruling dynasties, or the territories they controlled. Subsequently, Marcus (1976)argued that the "emblem glyphs" referred to archaeological sites, or more so the prominence and standing of the site, broken down in a 5-tiered hierarchy of asymmetrical distribution. Marcus' research assumed that the emblem glyphs were distributed in a pattern of relative site importance depending on broadness of distribution, roughly broken down as follows: Primary regional centers (capitals) (Tikal, Calakmul, and other "superpowers") were generally first in the region to acquire a unique emblem glyph(s). Texts referring to other primary regional centers occur in the texts of these "capitals", and dependencies exist which use the primary center's glyph. Secondary centers (Altun Ha, Lubaantun, Xunantunich, and other mid-sized cities) had their own glyphs but are only rarely mentioned in texts found in the primary regional center, while repeatedly mentioning the regional center in their own texts. Tertiary centers (towns) had no glyphs of their own, but have texts mentioning the primary regional centers and perhaps secondary regional centers on occasion. These were followed by the villages with no emblem glyphs and no texts mentioning the larger centers, and hamlets with little evidence of texts at all.[11] This model was largely unchallenged for over a decade until Mathews and Justeson,[12] as well as Houston,[13] argued once again that the "emblem glyphs" were the titles of Maya rulers with some geographical association.

The debate on the nature of "emblem glyphs" received a new spin in Stuart & Houston (1994). The authors demonstrated that there were many place-names-proper, some real, some mythological, mentioned in the hieroglyphic inscriptions. Some of these place names also appeared in the "emblem glyphs", some were attested in the "titles of origin" (expressions like "a person from Lubaantun"), but some were not incorporated in personal titles at all. Moreover, the authors also highlighted the cases when the "titles of origin" and the "emblem glyphs" did not overlap, building upon Houston's earlier research.[14] Houston noticed that the establishment and spread of the Tikal-originated dynasty in the Petexbatun region was accompanied by the proliferation of rulers using the Tikal "emblem glyph" placing political and dynastic ascendancy above the current seats of rulership.[15] Recent investigations also emphasize the use of emblem glyphs as an emic identifier to shape socio-political self-identity.[16]

Numerical system[edit]

The Mayas used a positional base-twenty (vigesimal) numerical system which only included whole numbers. For simple counting operations, a bar and dot notation was used. The dot represents 1 and the bar represents 5. A shell was used to represent zero. Numbers from 6 to 19 are formed combining bars and dots, and can be written horizontally or vertically.

Numbers over 19 are written vertically and read from the bottom to the top as powers of 20. The bottom number represents numbers from 0 to 20, so the symbol shown does not need to be multiplied. The second line from the bottom represents the amount of 20s there are, so that number is multiplied by 20. The third line from the bottom represents the amount of 400s, so it's multiplied by 400; the fourth by 8000; the fifth by 160,000, etc. Each successive line is an additional power of twenty (similar to how in Arabic numerals, additional powers of 10 are added to the right of the first digit). This positional system allows the calculation of large figures, necessary for chronology and astronomy.[17]

History[edit]

It was until recently thought that the Maya may have adopted writing from the Olmec or Epi-Olmec culture, who used the Isthmian script. However, murals excavated in 2005 have pushed back the origin of Maya writing by several centuries, and it now seems possible that the Maya were the ones who invented writing in Mesoamerica.[18] Scholarly consensus is that the Maya developed the only complete writing system in Mesoamerica.[19]

Knowledge of the Maya writing system continued into the early colonial era and reportedly[by whom?] a few of the early Spanish priests who went to Yucatán learned it. However, as part of his campaign to eradicate pagan rites, Bishop Diego de Landa ordered the collection and destruction of written Maya works, and a sizable number of Maya codices were destroyed. Later, seeking to use their native language to convert the Maya to Christianity, he derived what he believed to be a Maya "alphabet" (the so-called de Landa alphabet). Although the Maya did not actually write alphabetically, nevertheless he recorded a glossary of Maya sounds and related symbols, which was long dismissed as nonsense (for instance, by leading Mayanist J. E. S. Thompson in his 1950 book Maya Hieroglyphic Writing[20]) but eventually became a key resource in deciphering the Maya script, though it has itself not been completely deciphered. The difficulty was that there was no simple correspondence between the two systems, and the names of the letters of the Spanish alphabet meant nothing to Landa's Maya scribe, so Landa ended up asking things like write "ha": "hache–a", and glossed a part of the result as "H," which, in reality, was written as a-che-a in Maya glyphs.

Landa was also involved in creating an orthography, or a system of writing, for the Yukatek Maya language using the Latin alphabet. This was the first Latin orthography for any of the Mayan languages,[citation needed] which number around thirty.

Only four Maya codices are known to have survived the conquistadors.[21] Most surviving texts are found on pottery recovered from Maya tombs, or from monuments and stelae erected in sites which were abandoned or buried before the arrival of the Spanish.

Knowledge of the writing system was lost, probably by the end of the 16th century. Renewed interest in it was sparked by published accounts of ruined Maya sites in the 19th century.[21]

Decipherment[edit]

Deciphering Maya writing proved a long and laborious process. 19th-century and early 20th-century investigators managed to decode the Maya numbers[22] and portions of the texts related to astronomy and the Maya calendar, but understanding of most of the rest long eluded scholars. In the 1930s, Benjamin Whorf wrote a number of published and unpublished essays, proposing to identify phonetic elements within the writing system. Although some specifics of his decipherment claims were later shown to be incorrect, the central argument of his work, that Maya hieroglyphs were phonetic (or more specifically, syllabic), was later supported by the work of Yuri Knorozov(1922–1999), who played a major role in deciphering Maya writing.[23] Napoleon Cordy also made some notable contributions in the 1930s and 1940s to the early study and decipherment of Maya script, including "Examples of Phonetic Construction in Maya Hieroglyphs", in 1946.[24] In 1952 Knorozov published the paper "Ancient Writing of Central America", arguing that the so-called "de Landa alphabet" contained in Bishop Diego de Landa's manuscript Relación de las Cosas de Yucatán was made of syllabic, rather than alphabetic symbols. He further improved his decipherment technique in his 1963 monograph "The Writing of the Maya Indians"[25] and published translations of Maya manuscripts in his 1975 work "Maya Hieroglyphic Manuscripts". In the 1960s, progress revealed the dynastic records of Maya rulers. Since the early 1980s scholars have demonstrated that most of the previously unknown symbols form a syllabary, and progress in reading the Maya writing has advanced rapidly since.

As Knorozov's early essays contained several older readings already published in the late 19th century by Cyrus Thomas,[26] and the Soviet editors added propagandistic claims[27] to the effect that Knorozov was using a peculiarly "Marxist-Leninist" approach to decipherment,[27] many Western Mayanists simply dismissed Knorozov's work. However, in the 1960s, more came to see the syllabic approach as potentially fruitful, and possible phonetic readings for symbols whose general meaning was understood from context began to develop. Prominent older epigrapher J. Eric S. Thompson was one of the last major opponents of Knorozov and the syllabic approach. Thompson's disagreements are sometimes said to have held back advances in decipherment.[28] For example, Coe (1992, p. 164) says "the major reason was that almost the entire Mayanist field was in willing thrall to one very dominant scholar, Eric Thompson". G. Ershova, a student of Knorozov's, stated that reception of Knorozov's work was delayed only by authority of Thompson, and thus has nothing to do with Marxism – "But he (Knorozov) did not even suspect what a storm of hatred his success had caused in the head of the American school of Mayan studies, Eric Thompson. And the Cold War was absolutely nothing to do with it. An Englishman by birth, Eric Thompson, after learning about the results of the work of a young Soviet scientist, immediately realized 'who got the victory'."[29]

In 1959, examining what she called "a peculiar pattern of dates" on stone monument inscriptions at the Classic Maya site of Piedras Negras, Russian-American scholar Tatiana Proskouriakoffdetermined that these represented events in the lifespan of an individual, rather than relating to religion, astronomy, or prophecy, as held by the "old school" exemplified by Thompson. This proved to be true of many Maya inscriptions, and revealed the Maya epigraphic record to be one relating actual histories of ruling individuals: dynastic histories similar in nature to those recorded in other human cultures throughout the world. Suddenly, the Maya entered written history.[30]

Although it was then clear what was on many Maya inscriptions, they still could not literally be read. However, further progress was made during the 1960s and 1970s, using a multitude of approaches including pattern analysis, de Landa's "alphabet", Knorozov's breakthroughs, and others. In the story of Maya decipherment, the work of archaeologists, art historians, epigraphers, linguists, and anthropologists cannot be separated. All contributed to a process that was truly and essentially multidisciplinary. Key figures included David Kelley, Ian Graham, Gilette Griffin, and Michael Coe.

A new wave of breakthroughs occurred in the early 1970s, in particular at the first Mesa Redonda de Palenque, a scholarly conference organized by Merle Greene Robertson at the Maya site of Palenque and held in December, 1973. A working group consisting of Linda Schele, then a studio artist and art instructor, Floyd Lounsbury, a linguist from Yale, and Peter Mathews, then an undergraduate student of David Kelley's at the University of Calgary (whom Kelley sent because he could not attend). In one afternoon they reconstructed most of the dynastic list of Palenque, building on the earlier work of Heinrich Berlin.[31][3] By identifying a sign as an important royal title (now read as the recurring name Kʼinich), the group was able to identify and "read" the life histories (from birth, to accession to the throne, to death) of six kings of Palenque.[32][3] Palenque was the focus of much epigraphic work through the late 1970s, but linguistic decipherment of texts remained very limited.

From that point, progress proceeded rapidly. Scholars such as J. Kathryn Josserand, Nick Hopkins and others published findings that helped to construct a Mayan vocabulary.[33] The "old school" continued to resist the results of the new scholarship for some time. A decisive event which helped to turn the tide in favor of the new approach occurred in 1986, at an exhibition entitled "The Blood of Kings: A New Interpretation of Maya Art", organized by InterCulturaand the Kimbell Art Museum and curated by Schele and by Yale art historian Mary Miller. This exhibition and its attendant catalogue—and international publicity—revealed to a wide audience the new world which had latterly been opened up by progress in decipherment of Maya hieroglyphics. Not only could a real history of ancient America now be read and understood, but the light it shed on the material remains of the Maya showed them to be real, recognisable individuals. They stood revealed as a people with a history like that of all other human societies: full of wars, dynastic struggles, shifting political alliances, complex religious and artistic systems, expressions of personal property and ownership and the like. Moreover, the new interpretation, as the exhibition demonstrated, made sense out of many works of art whose meaning had been unclear and showed how the material culture of the Maya represented a fully integrated cultural system and world-view. Gone was the old Thompson view of the Maya as peaceable astronomers without conflict or other attributes characteristic of most human societies.

However, three years later, in 1989, supporters who continued to resist the modern decipherment interpretation made their last argument against it. This occurred at a conference at Dumbarton Oaks. It did not directly attack the methodology or results of decipherment, but instead contended that the ancient Maya texts had indeed been read but were "epiphenomenal". This argument was extended from a populist perspective to say that the deciphered texts tell only about the concerns and beliefs of the society's elite, and not about the ordinary Maya. In opposition to this idea, Michael Coe described "epiphenomenal" as "a ten penny word meaning that Maya writing is only of marginal application since it is secondary to those more primary institutions—economics and society—so well studied by the dirt archaeologists."[34]

Linda Schele noted following the conference that this is like saying that the inscriptions of ancient Egypt—or the writings of Greek philosophers or historians—do not reveal anything important about their cultures. Most written documents in most cultures tell us about the elite, because in most cultures in the past, they were the ones who could write (or could have things written down by scribes or inscribed on monuments).[citation needed]

Over 90 percent of the Maya texts can now be read with reasonable accuracy.[3] As of 2020, at least one phonetic glyph was known for each of the syllables marked green in this chart. /tʼ/ is rare. /pʼ/ is not found, and is thought to have been a later innovation in the Ch'olan and Yucatecan languages.

| (ʼ) | b | ch | chʼ | h | j | k | kʼ | l | m | n | p | s | t | tʼ | tz | tzʼ | w | x | y | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| a | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| e | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | ? | Yes | |

| i | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ||

| o | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | |

| u | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | ? | Yes | Yes |

Syllables[edit]

Syllables are in the form of consonant + vowel. The top line contains individual vowels. In the left column are the consonants with their pronunciation instructions. The apostrophe ' represents the glottal stop. There are different variations of the same character in the table cell. Blank cells are bytes whose characters are not yet known.[37]

| a | e | i | o | u | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|  |  |  |   | |

| b |    |   |  | ||

| ch /tš/ |   |  |  | ||

| ch’ |  |  | |||

| h /h/ |  | ||||

| j /x/ |   |  |  |  | |

| k |  |   |  |   | |

| k’ |  |  |  |  |  |

| l |  |  |  | ||

| m |  |  | |||

| n |   |  |  |  |  |

| p |   |  |  |  | |

| s |   |  | |||

| t |   |  |  |  | |

| t’ |  | ||||

| tz /ts/ |  |  |  |  | |

| tz’ |  | ||||

| w |  | ||||

| x /š/ |  |  |  | ||

| y /j/ |  |  | |||

| a | e | i | o | u |

Example[edit]

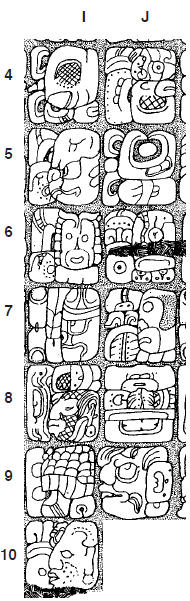

Tomb of Kʼinich Janaabʼ Pakal:

| Row | Glyphs | Reading | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| I | J | I | J | |

| 4 | ya k’a wa | ʔu(?) K’UH hu lu | yak’aw | ʔuk’uhul |

| 5 | PIK | 1-WINAAK-ki | pik | juʔn winaak |

| 6 | pi xo ma | ʔu SAK hu na la | pixoʔm | ʔusak hunal |

| 7 | ʔu-ha | YAX K’AHK’ K’UH? | ʔuʔh | Yax K’ahk’ K’uh? |

| 8 | ʔu tu pa | K’UH? ? | ʔutuʔp | k’uh(ul)? ...l |

| 9 | ʔu KOʔHAW wa | ?[CHAAK] ...m | ʔukoʔhaw | Chaahk (‘GI’) |

| 10 | SAK BALUʔN | - | Sak Baluʔn | - |

Text: Yak’aw ʔuk’uhul pik juʔn winaak pixoʔm ʔusak hunal ʔuʔh Yax K’ahk’ K’uh(?) ʔutuʔp k’uh(ul)? ...l ʔukoʔhaw Chaahk (‘GI’) Sak Baluʔn.

Translation: «He gave the god clothing, [consisted of] twenty nine headgears, white ribbon, necklace, First Fire God’s earrings and God’s quadrilateral badge helmet, to Chaahk Sak-Balun».

Revival[edit]

In recent times, there has been an increased interest in reviving usage of the script. Various works have recently been both transliterated and created into the script, notably the transcription of the Popol Vuh in 2018, a record of Kʼicheʼ religion. Another example is the sculpting and writing of a modern steleplaced at Iximche in 2012, describing the full historical record of the site dating back to the beginning of the Mayan long count.[38] Modern poems such as "Cigarra" by Martín Gómez Ramírez have also been recently written entirely within the script.[39]

Computer encoding[edit]

With the renewed usage of Maya writing, digital encoding of the script has been of recent interest.[40] but currently Maya script cannot be represented in any computer character encoding. A range of code points (U+15500–U+159FF) has been tentatively allocated for Unicode, but no detailed proposal has been submitted yet.[41] The Script Encoding Initiative project of the University of California, Berkeley, was awarded a grant in June 2016 to create a proposal to the Unicode Consortium for layout and presentation mechanisms in Unicode text, which was expected to be completed in 2017;[42] though as of 2023 they have not completed this project.[43]

The goal of encoding Maya hieroglyphs in Unicode is to facilitate the modern use of the script. For representing the degree of flexibility and variation of classical Maya, the expressiveness of Unicode is insufficient (e.g., with regard to the representation of infixes, i.e., signs inserted into other signs), so, for philological applications, different technologies are required.[44]

The Mayan numerals, with values 0–1910 creating a base-20 system, are encoded in block Mayan Numerals.

show This article may be expanded with text translated from the corresponding article in Spanish. (May 2022)Click [show] for important translation instructions.

The Aztec or Nahuatl script is a pre-Columbian writing system that combines ideographic writing with Nahuatl specific phonetic logograms and syllabic signs[1] which was used in central Mexico by the Nahua people. Origin[edit]The Aztec writing system derives from writing systems used in Central Mexico, such as Zapotec script. Mixtec writing is also thought to descend from Zapotec. The first Oaxacan inscriptions are thought to encode Zapotec, partially because of numerical suffixes characteristic of the Zapotec languages.[2] Structure and use[edit]Aztec was pictographic and ideographic proto-writing, augmented by phonetic rebuses. It also contained syllabic signs and logograms. There was no alphabet, but puns also contributed to recording sounds of the Aztec language. While some scholars have understood the system not to be considered a complete writing system, this is disputed by others. The existence of logograms and syllabic signs is being documented and a phonetic aspect of the writing system has emerged,[1] even though many of the syllabic characters have been documented since at least 1888 by Nuttall.[3] There are conventional signs for syllables and logograms which act as word signs or for their rebus content.[3] Logosyllabic writing appears on both painted and carved artifacts, such as the Tizoc Stone.[4] However, instances of phonetic characters often appear within a significant artistic and pictorial context. In native manuscripts, the sequence of historical events is indicated by a line of footprints leading from one place or scene to another. The ideographic nature of the writing is apparent in abstract concepts, such as death, represented by a corpse wrapped for burial; night, drawn as a black sky and a closed eye; war, by a shield and a club; and speech, illustrated as a little scroll issuing from the mouth of the person who is talking. The concepts of motion and walking were indicated by a trail of footprints.[5] A glyph could be used as a rebus to represent a different word with the same sound or similar pronunciation. This is especially evident in the glyphs of town names.[6] For example, the glyph for Tenochtitlan, the Aztec capital, was represented by combining two pictograms: stone (te-tl) and cactus (nochtli). Aztec Glyphs do not have a set reading order, unlike Maya hieroglyphs. As such, they may be read in any direction which forms the correct sound values in the context of the glyph. However, there is an internal reading order in that any sign will be followed by the next sign for the following sound in the word being written. They do not jumble up the sounds in a word. Numerals[edit]The Aztec numerical system was vigesimal. They indicated quantities up to twenty by the requisite number of dots. A flag was used to indicate twenty, repeating it for quantities up to four hundred, while a sign like a fir tree, meaning numerous as hairs, signified four hundred. The next unit, eight thousand, was indicated by an incense bag, which referred to the almost innumerable contents of a sack of cacao beans.[7] Historical[edit]Aztecs embraced the widespread manner of presenting history cartographically. A cartographic map would hold an elaborately detailed history recording events. The maps were painted to be read in sequence, so that time is established by the movement of the narrative through the map and by the succession of individual maps. Aztecs also used continuous year-count annals to record anything that would occur during that year. All the years are painted in a sequence and most of the years are generally in a single straight line that reads continually from left to right. Events, such as solar eclipses, floods, droughts, or famines, are painted around the years, often linked to the years by a line or just painted adjacent to them. Specific individuals were not mentioned often, but unnamed humans were often painted in order to represent actions or events.[8] When individuals are named, they form the majority of the corpus of logosyllabic examples. | |||||||||||||||||||

No comments:

Post a Comment