Ayers Rock: The story of the time includes the age of from to the landing in the stories that are an oral remedy to the ongoing mathematics of the concept of Cantor Arithmetic. This is the basis of what is "how did time measure", a volume of that to the what is the copy in form making the "matching Sphinx a given as the story to Egypt is that there is another Sphinx" to find. The religion of Islam has an "Black rock' oral tradition and another balance to a rock that has fallen from the sky. These time skates make the difference "Time" and the balance of that is the oral verb to description bringing Cantore mathematics to the Egyptian map of the angle to the belt of Orion.

This balance as the pyramid around the world all balance an angle remaining Pythagoras to what is the diameter to the constant.

The question to add to the Cantore geometric shape at only algebra is: How long does it take to "Ship" a light year to a destination? Is it possible to figure in Cantore arithmetic the time that it takes to travel a light-year and is it possible that these rocks tell more than a tale? The proof is in Cantore arithmetic.

In addition: The balance at Cantore biology would have to enhance the bio-firm: Are we marsupials and not homo sapiens? Refer: Aristotle

Uluru

| Uluru | |

|---|---|

| Ayers Rock | |

Aerial view of Uluru in 2007 | |

| Highest point | |

| Elevation | 863 m (2,831 ft) |

| Prominence | 348 m (1,142 ft) |

| Coordinates | 25°20′42″S 131°02′10″ECoordinates: 25°20′42″S 131°02′10″E |

| Naming | |

| Native name | Uluṟu (Pitjantjatjara) |

| Geography | |

| Geology | |

| Age of rock | 550–530 Ma |

| Mountain type | Inselberg |

| Type of rock | Arkose |

|

| |

| Official name | Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park |

| Criteria | v,vi,vii,ix |

| Reference | 447 |

| Inscription | 1987 (11th Session) |

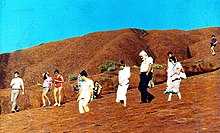

Uluru (/ˌuːləˈruː/; Pitjantjatjara: Uluṟu [ˈʊlʊɻʊ]), also known as Ayers Rock (/ˈɛərz/ AIRS) and officially gazetted as Uluru / Ayers Rock,[1] is a large sandstone formation in the southern part of the Northern Territory in Australia. It lies 335 km (208 mi) southwest of the nearest large town: Alice Springs.

Uluru is sacred to the Pitjantjatjara, the Aboriginal people of the area, known as the Aṉangu. The area around the formation is home to an abundance of springs, waterholes, rock caves, and ancient paintings. Uluru is listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. Uluru and Kata Tjuta, also known as the Olgas, are the two major features of the Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park.

Uluru is one of Australia's most recognisable natural landmarks and has been a popular destination for tourists since the late 1930s. It is also one of the most important indigenous sites in Australia.

Name

The local Aṉangu, the Pitjantjatjara people, call the landmark Uluṟu (Pitjantjatjara: [ʊlʊɻʊ]). This word is a proper noun, with no further particular meaning in the Pitjantjatjara dialect, although it is used as a local family name by the senior traditional owners of Uluru.[2]

On 19 July 1873, the surveyor William Gosse sighted the landmark and named it Ayers Rock in honour of the then Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.[3] Since then, both names have been used.

In 1993, a dual naming policy was adopted that allowed official names that consist of both the traditional Aboriginal name (in the Pitjantjatjara, Yankunytjatjara and other local languages) and the English name. On 15 December 1993, it was renamed "Ayers Rock / Uluru" and became the first official dual-named feature in the Northern Territory. The order of the dual names was officially reversed to "Uluru / Ayers Rock" on 6 November 2002 following a request from the Regional Tourism Association in Alice Springs.[4]

Description

The sandstone formation stands 348 m (1,142 ft) high, rising 863 m (2,831 ft) above sea level with most of its bulk lying underground, and has a total perimeter of 9.4 km (5.8 mi).[5] Both Uluru and the nearby Kata Tjuta formation have great cultural significance for the local Aṉangu people, the traditional inhabitants of the area, who lead walking tours to inform visitors about the bush, food, local flora and fauna, and the Aboriginal dreamtime stories of the area.

Uluru is also very notable for appearing to change colour at different times of the day and year, most notably, when it glows red at dawn and sunset.

Kata Tjuta, also called Mount Olga or the Olgas, lies 25 km (16 mi) west of Uluru. Special viewing areas with road access and parking have been constructed to give tourists the best views of both sites at dawn and dusk.

Geology

Uluru is an inselberg, meaning "island mountain".[6][7][8] An inselberg is a prominent isolated residual knob or hill that rises abruptly from and is surrounded by extensive and relatively flat erosion lowlands in a hot, dry region.[9] Uluru is also often referred to as a monolith, although this is an ambiguous term that is generally avoided by geologists.[10]

The remarkable feature of Uluru is its homogeneity and lack of jointing and parting at bedding surfaces, leading to the lack of development of scree slopes and soil. These characteristics led to its survival, while the surrounding rocks were eroded.[10]

For the purpose of mapping and describing the geological history of the area, geologists refer to the rock strata making up Uluru as the Mutitjulu Arkose, and it is one of many sedimentary formations filling the Amadeus Basin.[6]

Composition

Uluru is dominantly composed of coarse-grained arkose (a type of sandstone characterised by an abundance of feldspar) and some conglomerate.[6][11] Average composition is 50% feldspar, 25–35% quartz and up to 25% rock fragments; most feldspar is K-feldspar with only minor plagioclase as subrounded grains and highly altered inclusions within K-feldspar.[6] The grains are typically 2–4 millimetres (0.079–0.157 in) in diameter, and are angular to subangular; the finer sandstone is well sorted, with sorting decreasing with increasing grain size.[6] The rock fragments include subrounded basalt, invariably replaced to various degrees by chlorite and epidote.[6] The minerals present suggest derivation from a predominantly granite source, similar to the Musgrave Block exposed to the south.[10] When relatively fresh, the rock has a grey colour, but weathering of iron-bearing minerals by the process of oxidation gives the outer surface layer of rock a red-brown rusty colour.[6] Features related to deposition of the sediment include cross-bedding and ripples, analysis of which indicated deposition from broad shallow high energy fluvial channels and sheet flooding, typical of alluvial fans.[6][10]

Age and origin

The Mutitjulu Arkose is believed to be of about the same age as the conglomerate at Kata Tjuta, and to have a similar origin despite the rock type being different, but it is younger than the rocks exposed to the east at Mount Conner,[6] and unrelated to them. The strata at Uluru are nearly vertical, dipping to the south west at 85°, and have an exposed thickness of at least 2,400 m (7,900 ft). The strata dip below the surrounding plain and no doubt extend well beyond Uluru in the subsurface, but the extent is not known.

The rock was originally sand, deposited as part of an extensive alluvial fan that extended out from the ancestors of the Musgrave, Mann and Petermann Ranges to the south and west, but separate from a nearby fan that deposited the sand, pebbles and cobbles that now make up Kata Tjuta.[6][10]

The similar mineral composition of the Mutitjulu Arkose and the granite ranges to the south is now explained. The ancestors of the ranges to the south were once much larger than the eroded remnants we see today. They were thrust up during a mountain building episode referred to as the Petermann Orogeny that took place in late Neoproterozoic to early Cambrian times (550–530 Ma), and thus the Mutitjulu Arkose is believed to have been deposited at about the same time.

The arkose sandstone which makes up the formation is composed of grains that show little sorting based on grain size, exhibit very little rounding and the feldspars in the rock are relatively fresh in appearance. This lack of sorting and grain rounding is typical of arkosic sandstones and is indicative of relatively rapid erosion from the granites of the growing mountains to the south. The layers of sand were nearly horizontal when deposited, but were tilted to their near vertical position during a later episode of mountain building, possibly the Alice Springs Orogeny of Palaeozoic age (400–300 Ma).[6]

Fauna and flora

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Historically, 46 species of native mammals are known to have been living near Uluru; according to recent surveys there are currently 21. Aṉangu acknowledge that a decrease in the number has implications for the condition and health of the landscape. Moves are supported for the reintroduction of locally extinct animals such as malleefowl, common brushtail possum, rufous hare-wallaby or mala, bilby, burrowing bettong, and the black-flanked rock-wallaby.[12][13][14]

The mulgara is mostly restricted to the transitional sand plain area, a narrow band of country that stretches from the vicinity of Uluru to the northern boundary of the park and into Ayers Rock Resort. This area also contains the marsupial mole, woma python, and great desert skink.

The bat population of the park comprises at least seven species that depend on day roosting sites within caves and crevices of Uluru and Kata Tjuta. Most of the bats forage for aerial prey within 100 m (330 ft) or so from the rock face. The park has a very rich reptile fauna of high conservation significance, with 73 species having been reliably recorded. Four species of frogs are abundant at the base of Uluru and Kata Tjuta following summer rains. The great desert skink is listed as vulnerable.

Aṉangu continue to hunt and gather animal species in remote areas of the park and on Aṉangu land elsewhere. Hunting is largely confined to the red kangaroo, bush turkey, emu, and lizards such as the sand goanna and perentie.

Of the 27 mammal species found in the park, six are introduced: the house mouse, camel, fox, cat, dog, and rabbit. These species are distributed throughout the park, but their densities are greatest near the rich water run-off areas of Uluru and Kata Tjuta.

Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park flora represents a large portion of plants found in Central Australia. A number of these species are considered rare and restricted in the park or the immediate region. Many rare and endemic plants are found in the park.

The growth and reproduction of plant communities rely on irregular rainfall. Some plants are able to survive fire and some are dependent on it to reproduce. Plants are an important part of Tjukurpa, and ceremonies are held for each of the major plant foods. Many plants are associated with ancestral beings.

Flora in Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park can be broken into these categories:

- Punu – trees

- Puti – shrubs

- Tjulpun-tjulpunpa – flowers

- Ukiri – grasses

Trees such as the mulga and centralian bloodwood are used to make tools such as spearheads, boomerangs, and bowls. The red sap of the bloodwood is used as a disinfectant and an inhalant for coughs and colds.

Several rare and endangered species are found in the park. Most of them, like adder's tongue ferns, are restricted to the moist areas at the base of the formation, which are areas of high visitor use and subject to erosion.

Since the first Europeans arrived, 34 exotic plant species have been recorded in the park, representing about 6.4% of the total park flora. Some, such as perennial buffel grass (Cenchrus ciliaris), were introduced to rehabilitate areas damaged by erosion. It is the most threatening weed in the park and has spread to invade water- and nutrient-rich drainage lines. A few others, such as burrgrass, were brought in accidentally, carried on cars and people.

Climate and five seasons

The park has a hot desert climate and receives an average rainfall of 284.6 mm (11.2 in) per year.[15] The average high temperature in summer (December–January) is 37.8 °C (100.0 °F), and the average low temperature in winter (June–July) is 4.7 °C (40.5 °F). Temperature extremes in the park have been recorded at 46 °C (115 °F) during summer and −5 °C (23 °F) during winter. UV levels are extreme between October and March, averaging between 11 and 15 on the UV index.[16][17]

Local Aboriginal people recognise five seasons:[5]

- Wanitjunkupai (April/May) – Cooler weather

- Wari (June/July) – Cold season bringing morning frosts

- Piriyakutu (August/September/October) – Animals breed and food plants flower

- Mai Wiyaringkupai (November/December) – The hot season when food becomes scarce

- Itjanu (January/February/March) – Sporadic storms can roll in suddenly

| Climate data for Yulara Aero | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 46.4 (115.5) |

45.8 (114.4) |

42.9 (109.2) |

39.6 (103.3) |

35.7 (96.3) |

36.4 (97.5) |

31.1 (88.0) |

35.0 (95.0) |

38.7 (101.7) |

42.3 (108.1) |

45.0 (113.0) |

47.0 (116.6) |

47.0 (116.6) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 38.4 (101.1) |

36.9 (98.4) |

34.4 (93.9) |

29.8 (85.6) |

24.2 (75.6) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.4 (68.7) |

23.7 (74.7) |

28.8 (83.8) |

32.4 (90.3) |

35.1 (95.2) |

36.5 (97.7) |

30.1 (86.2) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 22.7 (72.9) |

22.1 (71.8) |

19.3 (66.7) |

14.4 (57.9) |

9.3 (48.7) |

5.6 (42.1) |

4.4 (39.9) |

5.9 (42.6) |

10.7 (51.3) |

15.0 (59.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

20.8 (69.4) |

14.1 (57.4) |

| Record low °C (°F) | 12.7 (54.9) |

12.1 (53.8) |

8.0 (46.4) |

1.3 (34.3) |

1.1 (34.0) |

−1.8 (28.8) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−1 (30) |

4.5 (40.1) |

6.5 (43.7) |

9.9 (49.8) |

−3.6 (25.5) |

| Average rainfall mm (inches) | 25.8 (1.02) |

39.6 (1.56) |

35.1 (1.38) |

14.7 (0.58) |

13.0 (0.51) |

17.4 (0.69) |

18.4 (0.72) |

4.3 (0.17) |

7.4 (0.29) |

20.7 (0.81) |

34.2 (1.35) |

40.2 (1.58) |

274.6 (10.81) |

| Average rainy days (≥ 1 mm) | 3.2 | 2.9 | 2.0 | 1.7 | 1.8 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.0 | 1.4 | 2.7 | 3.9 | 4.7 | 28.8 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[15] | |||||||||||||

Aboriginal myths, legends and traditions

According to the Aṉangu, traditional landowners of Uluru:[18]

The world was once a featureless place. None of the places we know existed until creator beings, in the forms of people, plants and animals, traveled widely across the land. Then, in a process of creation and destruction, they formed the landscape as we know it today. Aṉangu land is still inhabited by the spirits of dozens of these ancestral creator beings which are referred to as Tjukuritja or Waparitja.

There are a number of differing accounts given, by outsiders, of Aboriginal ancestral stories for the origins of Uluru and its many cracks and fissures. One such account, taken from Robert Layton's (1989) Uluru: An Aboriginal history of Ayers Rock,[19] reads as follows:

Uluru was built up during the creation period by two boys who played in the mud after rain. When they had finished their game they travelled south to Wiputa ... Fighting together, the two boys made their way to the table topped Mount Conner, on top of which their bodies are preserved as boulders. (Page 5)

Two other accounts are given in Norbert Brockman's (1997) Encyclopedia of Sacred Places.[20] The first tells of serpent beings who waged many wars around Uluru, scarring the rock. The second tells of two tribes of ancestral spirits who were invited to a feast, but were distracted by the beautiful Sleepy Lizard Women and did not show up. In response, the angry hosts sang evil into a mud sculpture that came to life as the dingo. There followed a great battle, which ended in the deaths of the leaders of both tribes. The earth itself rose up in grief at the bloodshed, becoming Uluru.

The Commonwealth Department of Environment's webpage advises:[18]

Many...Tjukurpa such as Kalaya (Emu), Liru (poisonous snake), Lungkata (blue tongue lizard), Luunpa (kingfisher) and Tjintir-tjintirpa (willie wagtail) travel through Uluṟu-Kata Tjuṯa National Park. Other Tjukurpa affect only one specific area.

Kuniya, the woma python, lived in the rocks at Uluru where she fought the Liru, the poisonous snake.

It is sometimes reported that those who take rocks from the formation will be cursed and suffer misfortune. There have been many instances where people who removed such rocks attempted to mail them back to various agencies in an attempt to remove the perceived curse.[21][22]

History

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Ancient human settlement

Archaeological findings to the east and west indicate that humans settled in the area more than 10,000 years ago.[19]

European arrival (1870s)

Europeans arrived in the Australian Western Desert in the 1870s. Uluru and Kata Tjuta were first mapped by Europeans in 1872 during the expeditionary period made possible by the construction of the Australian Overland Telegraph Line. In separate expeditions, Ernest Giles and William Gosse were the first European explorers to this area. While exploring the area in 1872, Giles sighted Kata Tjuta from a location near Kings Canyon and called it Mount Olga, while the following year Gosse observed Uluru and named it Ayers' Rock, in honour of the Chief Secretary of South Australia, Sir Henry Ayers.

European colonisation

Further explorations followed with the aim of establishing the possibilities of the area for pastoralism. In the late 19th century, pastoralists attempted to establish themselves in areas adjoining the Southwestern/Petermann Reserve and interaction between Aṉangu and white people became more frequent and more violent. Due to the effects of grazing and drought, bush food stores became depleted. Competition for these resources created conflict between the two groups, resulting in more frequent police patrols. Later, during the depression in the 1930s, Aṉangu became involved in dingo scalping with 'doggers' who introduced the Aṉangu to European foods and ways.

Aboriginal reserve (1920)

Between 1918 and 1921, large adjoining areas of South Australia, Western Australia, and the Northern Territory were declared as Aboriginal reserves, government-run settlements where the Aboriginal people were forced to live. In 1920, part of Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park was declared an Aboriginal Reserve (commonly known as the South-Western or Petermann Reserve) by the Australian government under the Aboriginals Ordinance 1918.[23]

Tourism (1936–1960s)

The first tourists arrived in the Uluru area in 1936. Permanent European settlement of the area began in the 1940s under Aboriginal welfare policy and to promote tourism at Uluru. This increased tourism prompted the formation of the first vehicular tracks in 1948 and tour bus services began early in the 1950s. In 1958, the area that would become the Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park was excised from the Petermann Reserve; it was placed under the management of the Northern Territory Reserves Board and named the Ayers Rock–Mount Olga National Park. The first ranger was Bill Harney, a well-recognised central Australian figure.[12] By 1959, the first motel leases had been granted and Eddie Connellan had constructed an airstrip close to the northern side of Uluru.[3] Following a 1963 suggestion from the Northern Territory Reserves Board, a chain was laid to assist tourists in climbing the landmark.[24] The chain was removed in 2019.

Aboriginal ownership since 1985

On 26 October 1985, the Australian government returned ownership of Uluru to the local Pitjantjatjara people, with one of the conditions being that the Aṉangu would lease it back to the National Parks and Wildlife agency for 99 years and that it would be jointly managed. An agreement originally made between the community and Prime Minister Bob Hawke that the climb to the top by tourists would be stopped was later broken.[25][26][27][28]

The Aboriginal community of Mutitjulu, with a population of approximately 300, is located near the eastern end of Uluru. From Uluru it is 17 km (11 mi) by road to the tourist town of Yulara, population 3,000, which is situated just outside the national park.

On 8 October 2009, the Talinguru Nyakuntjaku viewing area opened to public visitation. The A$21 million project about 3 kilometres (1.9 mi) on the east side of Uluru involved design and construction supervision by the Aṉangu traditional owners, with 11 kilometres (6.8 mi) of roads and 1.6 kilometres (1 mi) of walking trails being built for the area.[29][30]

Tourism

The development of tourism infrastructure adjacent to the base of Uluru that began in the 1950s soon produced adverse environmental impacts. It was decided in the early 1970s to remove all accommodation-related tourist facilities and re-establish them outside the park. In 1975, a reservation of 104 square kilometres (40 sq mi) of land beyond the park's northern boundary, 15 kilometres (9 mi) from Uluru, was approved for the development of a tourist facility and an associated airport, to be known as Yulara. The camp ground within the park was closed in 1983 and the motels closed in late 1984, coinciding with the opening of the Yulara resort. In 1992, the majority interest in the Yulara resort held by the Northern Territory Government was sold and the resort was renamed Ayers Rock Resort.

Since the park was listed as a World Heritage Site, annual visitor numbers rose to over 400,000 visitors by the year 2000.[31] Increased tourism provides regional and national economic benefits. It also presents an ongoing challenge to balance conservation of cultural values and visitor needs.

Climbing

On 11 December 1983, the Prime Minister of Australia, Bob Hawke, promised to hand back the land title to the Aṉangu traditional custodians and caretakers and agreed to the community's 10-point plan which included forbidding the climbing of Uluru. The government, however, set access to climb Uluru and a 99-year lease, instead of the previously agreed upon 50-year lease, as conditions before the title was officially given back to the Aṉangu on 26 October 1985.[25][32]

The local Aṉangu do not climb Uluru because of its great spiritual significance. They request that visitors do not climb the rock, partly due to the path crossing a sacred traditional Dreamtime track, and also due to a sense of responsibility for the safety of visitors. Until October 2019, the visitors guide said "the climb is not prohibited, but we prefer that, as a guest on Aṉangu land, you will choose to respect our law and culture by not climbing."[5]

According to a 2010 publication, just over one-third of all visitors to the park climbed Uluru; a high percentage of these were children.[33] A chain handhold added in 1964 and extended in 1976 made the hour-long climb easier,[34] but it remained a steep, 800 m (0.5 mi) hike to the top, where it can be quite windy.[35][36] It was recommended that individuals drink plenty of water while climbing, and that those who were unfit, or who suffered from vertigo or medical conditions restricting exercise, did not attempt it. Climbing Uluru was generally closed to the public when high winds were present at the top. There were at least 37 deaths relating to recreational climbing since such incidents began being recorded.[5][37] About one-sixth of visitors made the climb between 2011 and 2015.[38]

The traditional owners of Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park (Nguraritja) and the Federal Government's Director of National Parks share decision-making on the management of Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park. Under their joint Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park Management Plan 2010–20, issued by the Director of National Parks under the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, clause 6.3.3 provides that the Director and the Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa Board of Management should work towards closure of the climb and, additionally, that it was to be closed upon any of three conditions being met: there were "adequate new visitor experiences", less than 20 per cent of visitors made the climb, or the "critical factors" in decisions to visit were "cultural and natural experiences".[39] Despite cogent evidence that the second condition was met by July 2013, the climb remained open.[40]

Several controversial incidents on top of Uluru in 2010, including a striptease, golfing, and nudity, led to renewed calls for banning the climb.[41] On 1 November 2017, the Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park board voted unanimously to prohibit climbing Uluru.[42] As a result, there was a surge in climbers and visitors after the ban was announced.[43][44] The ban took effect on the 26 October 2019, and the chain was then removed.[45]

Photography

The Aṉangu request that visitors do not photograph certain sections of Uluru, for reasons related to traditional Tjukurpa (Dreaming) beliefs. These areas are the sites of gender-linked rituals or ceremonies and are forbidden ground for Aṉangu of the opposite sex to those participating in the rituals in question. The photographic restriction is intended to prevent Aṉangu from inadvertently violating this taboo by encountering photographs of the forbidden sites in the outside world.[46]

In September 2020, Parks Australia alerted Google Australia to the user-generated images from the Uluru summit that have been posted on the Google Maps platform and requested that the content be removed in accordance with the wishes of Aṉangu, Uluru's traditional owners, and the national park's Film and Photography Guidelines. Google agreed to the request.[47][48] Currently, the only photos of Uluru are photos at the surface.

Waterfalls

During heavy rain, waterfalls cascade down the sides of Uluru, a rare phenomenon that only 1% of all tourists get to see.[49] Large rainfall events occurred in 2016[50] and the summer of 2020-21.[51][52][53][54]

See also

- Death of Azaria Chamberlain

- Indigenous Australian art

- List of sandstones

- List of mountains of the Northern Territory

- Mount Augustus National Park

- Pitjantjatjara § Recognition of sacred sites

- Protected areas of the Northern Territory

- Tietkens expedition of 1889

References

- Notes

- "Waterfalls cascade down Uluru as severe weather brings heavy rain to NT". ABC News. 24 March 2021. Retrieved 24 March 2021.

- Bibliography

- Breeden, Stanley (1995). Growing Up at Uluru, Australia. Fortitude Valley, Queensland: Steve Parish Publishing. ISBN 0-947263-89-6. OCLC 34351662.

- Breeden, Stanley (2000) [1994]. Uluru: Looking After Uluru – Kata Tjuta, the Anangu Way. Roseville Chase, NSW: Simon & Schuster Australia. ISBN 0-7318-0359-0. OCLC 32470148.

- Hill, Barry (1 November 1994). The Rock: Travelling to Uluru. St Leonards, NSW: Allen & Unwin. ISBN 1-86373-778-2. OCLC 33146858.

- Mountford, Charles P. (1977) [1965]. Ayers Rock: Its People, Their Beliefs and Their Art. Adelaide: Rigby Publishing. ISBN 0-7270-0215-5. OCLC 6844898.

External links

![]() Media related to Uluru at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Uluru at Wikimedia Commons

- Uluṟu–Kata Tjuṯa National Park – Australian Department of the Environment and Water Resources

- Northern Territory official tourism site

Languages

The Black Stone (Arabic: ٱلْحَجَرُ ٱلْأَسْوَد, al-Ḥajaru al-Aswad, 'Black Stone') is a rock set into the eastern corner of the Kaaba, the ancient building in the center of the Grand Mosque in Mecca, Saudi Arabia. It is revered by Muslims as an Islamic relic which, according to Muslim tradition, dates back to the time of Adam and Eve.[1]

The stone was venerated at the Kaaba in pre-Islamic pagan times. According to Islamic tradition, it was set intact into the Kaaba's wall by the Islamic prophet Muhammad in 605 CE, five years before his first revelation. Since then it has been broken into fragments and is now cemented into a silver frame in the side of the Kaaba. Its physical appearance is that of a fragmented dark rock, polished smooth by the hands of pilgrims. Islamic tradition holds that it fell from heaven as a guide for Adam and Eve to build an altar. It has often been described as a meteorite.[2]

Muslim pilgrims circle the Kaaba as a part of the tawaf ritual during the hajj and many try to stop to kiss the Black Stone, emulating the kiss that Islamic tradition records that it received from Muhammad.[3][4] Muslims do not worship the Black Stone.[5][6]

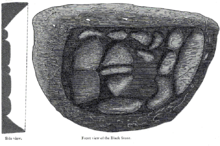

Physical description

The Black Stone was originally a single piece of rock but today consists of several pieces that have been cemented together. They are surrounded by a silver frame which is fastened by silver nails to the Kaaba's outer wall.[7] The fragments are themselves made up of smaller pieces which have been combined to form the seven or eight fragments visible today. The Stone's exposed face measures about 20 centimetres (7.9 in) by 16 centimetres (6.3 in). Its original size is unclear and the recorded dimensions have changed considerably over time, as the pieces have been rearranged in their cement matrix on several occasions.[2] In the 10th century, an observer described the Black Stone as being one cubit (46 cm or 18 in) long. By the early 17th century, it was recorded as measuring 140 by 122 cm (4 ft 7 in by 4 ft 0 in). According to Ali Bey in the 18th century, it was described as 110 cm (3 ft 7 in) high, and Muhammad Ali Pasha reported it as being 76 cm (2 ft 6 in) long by 46 cm (1 ft 6 in) wide.[2]

The Black Stone is attached to the east corner of the Kaaba, known as al-Rukn al-Aswad (the 'Corner of the Black Stone').[8] Another stone, known as the Hajar as-Sa’adah ('Stone of Felicity') is set into the Kaaba's opposite corner, al-Rukn al-Yamani (the 'Yemeni Corner'), at a somewhat lower height than the Black Stone.[9] The choice of the east corner may have had ritual significance; it faces the rain-bringing east wind (al-qabul) and the direction from which Canopus rises.[10]

The silver frame around the Black Stone and the black kiswah or cloth enveloping the Kaaba were for centuries maintained by the Ottoman Sultans in their role as Custodian of the Two Holy Mosques. The frames wore out over time due to the constant handling by pilgrims and were periodically replaced. Worn-out frames were brought back to Istanbul, where they are still kept as part of the sacred relics in the Topkapı Palace.[11]

Appearance of the Black Stone

The Black Stone was described by European travellers to Arabia in the 19th- and early-20th centuries, who visited the Kaaba disguised as pilgrims. Swiss traveller Johann Ludwig Burckhardt visited Mecca in 1814, and provided a detailed description in his 1829 book Travels in Arabia:

It is an irregular oval, about seven inches [18 cm] in diameter, with an undulated surface, composed of about a dozen smaller stones of different sizes and shapes, well joined together with a small quantity of cement, and perfectly well smoothed; it looks as if the whole had been broken into as many pieces by a violent blow, and then united again. It is very difficult to determine accurately the quality of this stone which has been worn to its present surface by the millions of touches and kisses it has received. It appeared to me like a lava, containing several small extraneous particles of a whitish and of a yellow substance. Its colour is now a deep reddish brown approaching to black. It is surrounded on all sides by a border composed of a substance which I took to be a close cement of pitch and gravel of a similar, but not quite the same, brownish colour. This border serves to support its detached pieces; it is two or three inches in breadth, and rises a little above the surface of the stone. Both the border and the stone itself are encircled by a silver band, broader below than above, and on the two sides, with a considerable swelling below, as if a part of the stone were hidden under it. The lower part of the border is studded with silver nails.[12]

Visiting the Kaaba in 1853, Richard Francis Burton noted that:

The colour appeared to me black and metallic, and the centre of the stone was sunk about two inches below the metallic circle. Round the sides was a reddish-brown cement, almost level with the metal, and sloping down to the middle of the stone. The band is now a massive arch of gold or silver gilt. I found the aperture in which the stone is, one span and three fingers broad.[13]

Ritter von Laurin, the Austrian consul-general in Egypt, was able to inspect a fragment of the Stone removed by Muhammad Ali in 1817 and reported that it had a pitch-black exterior and a silver-grey, fine-grained interior in which tiny cubes of a bottle-green material were embedded. There are reportedly a few white or yellow spots on the face of the Stone, and it is officially described as being white with the exception of the face.[2]

History and tradition

The Black Stone was held in reverence well before Islam. It had long been associated with the Kaaba, which was built in the pre-Islamic period and was a site of pilgrimage of Nabataeans who visited the shrine once a year to perform their pilgrimage. The Kaaba held 360 idols of the Meccan gods.[15][failed verification] The Semitic cultures of the Middle East had a tradition of using unusual stones to mark places of worship, a phenomenon which is reflected in the Hebrew Bible as well as the Quran.[16] However worshiping or praying to the stone is forbidden in Islam as per hadith reporting the saying of Omar,[17] while bowing, worshiping and praying to such sacred objects is also described in the Tanakh as idolatrous[18] and was the subject of prophetic rebuke.[19][20][21][22][23][24] The meteorite-origin theory of the Black Stone has seen it likened by some writers to the meteorite which was placed and worshipped in the Greek Temple of Artemis.[25][26][27]

The Kaaba has been associated with fertility rites of Arabia.[28][29][failed verification] Some writers remark on the apparent similarity of the Black Stone and its frame to the external female genitalia.[30][31] However, the silver frame was placed on the Black Stone to secure the fragments, after the original stone was broken.[32][33]

A "red stone" was associated with the deity of the south Arabian city of Ghaiman, and there was a "white stone" in the Kaaba of al-Abalat (near the city of Tabala, south of Mecca). Worship at that time period was often associated with stone reverence, mountains, special rock formations, or distinctive trees.[34] The Kaaba marked the location where the sacred world intersected with the profane, and the embedded Black Stone was a further symbol of this as an object as a link between heaven and earth.[35] Aziz Al-Azmeh claims that the divine name ar-Rahman (one of the names of God in Islam and cognate to one of the Jewish names of God Ha'Rachaman, both meaning "the Merciful One" or "the Gracious One")[36] was used for astral gods in Mecca and might have been associated with the Black Stone.[37] The stone is also thought to be associated with Allat.[38] Muhammad is said to have called the stone "the right hand of al-Rahman".[39]

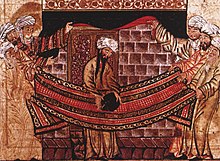

Muhammad

According to Islamic belief Muhammad is credited with setting the Black Stone in the current place in the wall of the Kaaba. A story found in Ibn Ishaq's Sirah Rasul Allah tells how the clans of Mecca renovated the Kaaba following a major fire which had partly destroyed the structure. The Black Stone had been temporarily removed to facilitate the rebuilding work. The clans could not agree on which one of them should have the honour of setting the Black Stone back in its place.[40][41]

They decided to wait for the next man to come through the gate and ask him to make the decision. That person was 35-year-old Muhammad, five years before his prophethood. He asked the elders of the clans to bring him a cloth and put the Black Stone in its centre. Each of the clan leaders held the corners of the cloth and carried the Black Stone to the right spot. Then, Muhammad set the stone in place, satisfying the honour of all of the clans.[40][41] After his Conquest of Mecca in 630, Muhammad is said to have ridden round the Kaaba seven times on his camel, touching the Black Stone with his stick in a gesture of reverence.[42]

Desecrations

The Stone has suffered repeated desecrations and damage over the course of time. It is said to have been struck and smashed to pieces by a stone fired from a catapult during the Umayyad Caliphate's siege of Mecca in 683. The fragments were rejoined by Abd Allah ibn al-Zubayr using a silver ligament.[40] In January 930, it was stolen by the Qarmatians, who carried the Black Stone away to their base in Hajar (modern Eastern Arabia). According to Ottoman historian Qutb al-Din, writing in 1857, the Qarmatian leader Abu Tahir al-Jannabi set the Black Stone up in his own mosque, the Masjid al-Dirar, with the intention of redirecting the hajj away from Mecca. This failed, as pilgrims continued to venerate the spot where the Black Stone had been.[42]

According to the historian al-Juwayni, the Stone was returned twenty-three years later, in 952. The Qarmatians held the Black Stone for ransom, and forced the Abbasids to pay a huge sum for its return. It was wrapped in a sack and thrown into the Friday Mosque of Kufa, accompanied by a note saying "By command we took it, and by command we have brought it back." Its abduction and removal caused further damage, breaking the stone into seven pieces.[16][43][44] Its abductor, Abu Tahir, is said to have met a terrible fate; according to Qutb al-Din, "the filthy Abu Tahir was afflicted with a gangrenous sore, his flesh was eaten away by worms, and he died a most terrible death." To protect the shattered stone, the custodians of the Kaaba commissioned a pair of Meccan goldsmiths to build a silver frame to surround it, and it has been enclosed in a similar frame ever since.[42]

In the 11th century, a man allegedly sent by the Fatimid caliph al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah attempted to smash the Black Stone but was killed on the spot, having caused only slight damage.[42] In 1674, according to Johann Ludwig Burckhardt, someone allegedly smeared the Black Stone with excrement so that "every one who kissed it retired with a sullied beard". According to the archaic Sunni belief,[45] by the accusation of one boy, the Persian of an unknown faith was suspected of sacrilege, where Sunnis of Mecca "have turned the circumstance to their own advantage" by assaulting, beating random Persians and forbidding them from Hajj until the ban was overturned by the order of Muhammad Ali. The explorer Sir Richard Francis Burton pointed out on the alleged "excrement action" that "it is scarcely necessary to say that a Shi'a, as well as a Sunni, would look upon such an action with lively horror", and that the real culprit was "some Jew or Christian, who risked his life to gratify a furious bigotry".[46]

Ritual role

The Black Stone plays a central role in the ritual of istilam, when pilgrims kiss the Black Stone, touch it with their hands or raise their hands towards it while repeating the takbir, "God is Greatest". They perform this in the course of walking seven times around the Kaaba in a counterclockwise direction (tawaf), emulating the actions of Muhammad. At the end of each circuit, they perform istilam and may approach the Black Stone to kiss it at the end of tawaf.[47] In modern times, large crowds make it practically impossible for everyone to kiss the stone, so it is currently acceptable to point in the direction of the Stone on each of their seven circuits around the Kaaba. Some even say that the Stone is best considered simply as a marker, useful in keeping count of the ritual circumambulations that one has performed.[48]

Writing in Dawn in Madinah: A Pilgrim's Progress, Muzaffar Iqbal described his experience of venerating the Black Stone during a pilgrimage to Mecca:

At the end of the second [circumambulation of the Kaaba], I was granted one of those extraordinary moments which sometimes occur around the Black Stone. As I approached the Corner the large crowd was suddenly pushed back by a strong man who had just kissed the Black Stone. This push generated a backward current, creating a momentary opening around the Black Stone as I came to it; I swiftly accepted the opportunity reciting, Bismillahi Allahu akbar wa lillahi-hamd ["In the name of God, God is great, all praise to God"], put my hands on the Black Stone and kissed it. Thousands of silver lines sparkled, the Stone glistened, and something stirred deep inside me. A few seconds passed. Then I was pushed away by the guard.[49]

The Black Stone and the Kaaba's opposite corner, al-Rukn al-Yamani, are both often perfumed by the mosque's custodians. This can cause problems for pilgrims in the state of ihram ("consecration"), who are forbidden from using scented products and will require a kaffara (donation) as a penance if they touch either.[50]

Meaning and symbolism

Islamic tradition holds that the Black Stone fell from Jannah to show Adam and Eve where to build an altar, which became the first temple on Earth.[51] Muslims believe that the stone was originally pure and dazzling white, but has since turned black because of the sins of the people who touch it.[52][53] Its black colour is deemed to symbolize the essential spiritual virtue of detachment and poverty for God (faqr) and the extinction of ego required to progress towards God (qalb).[16]

According to a prophetic tradition, "Touching them both (the Black Stone and al-Rukn al-Yamani) is an expiation for sins."[54] Adam's altar and the stone were said to have been lost during Noah's Flood and forgotten. Ibrahim (Abraham) was said to have later found the Black Stone at the original site of Adam's altar when the angel Jibrail revealed it to him.[16] Ibrahim ordered his son Ismael – who in Muslim belief is an ancestor of Muhammad – to build a new temple, the Kaaba, into which the stone was to be embedded.

Another tradition says that the Black Stone was originally an angel that had been placed by God in the Garden of Eden to guard Adam. The angel was absent when Adam ate the forbidden fruit and was punished by being turned into a jewel – the Black Stone. God granted it the power of speech and placed it at the top of Abu Qubays, a mountain in the historic region of Khurasan, before moving the mountain to Mecca. When Ibrahim took the Black Stone from Abu Qubays to build the Kaaba, the mountain asked Ibrahim to intercede with God so that it would not be returned to Khurasan and would stay in Mecca.[55]

According to some scholars, the Black Stone was the same stone that Islamic tradition describes as greeting Muhammad before his prophethood. This led to a debate about whether the Black Stone's greeting comprised actual speech or merely a sound, and following that, whether the stone was a living creature or an inanimate object. Whichever was the case, the stone was held to be a symbol of prophethood.[55]

A hadith records that, when the second Caliph Umar ibn al-Khattab (580–644) came to kiss the stone, he said in front of all assembled: "No doubt, I know that you are a stone and can neither harm anyone nor benefit anyone. Had I not seen Allah's Messenger [Muhammad] kissing you, I would not have kissed you."[56] In the hadith collection Kanz al-Ummal, it is recorded that Ali responded to Umar, saying, "This stone (Hajar Aswad) can indeed benefit and harm. ... Allah says in Quran that he created human beings from the progeny of Adam and made them witness over themselves and asked them, 'Am I not your creator?' Upon this, all of them confirmed it. Thus Allah wrote this confirmation. And this stone has a pair of eyes, ears and a tongue and it opened its mouth upon the order of Allah, who put that confirmation in it and ordered to witness it to all those worshippers who come for Hajj."[57]

Muhammad Labib al-Batanuni, writing in 1911, commented on the practice that the pre-Islamic practice of venerating stones (including the Black Stone) arose not because such stones are "sacred for their own sake, but because of their relation to something holy and respected".[58] The Indian Islamic scholar Muhammad Hamidullah summed up the meaning of the Black Stone:

[T]he Prophet has named the (Black Stone) the "right hand of God" (yamin-Allah), and for purpose. In fact one poses there one's hand to conclude the pact, and God obtains there our pact of allegiance and submission. In the quranic terminology, God is the king, and ... in (his) realm there is a metropolis (Umm al-Qurra) and in the metropolis naturally a palace (Bait-Allah, home of God). If a subject wants to testify to his loyalty, he has to go to the royal palace and conclude personally the pact of allegiance. The right hand of the invisible God must be visible symbolically. And that is the al-Hajar al-Aswad, the Black Stone in the Ka'bah.[59]

In recent years several literalist views of the Black Stone have emerged. A small minority accepts as literally true a hadith, usually taken as allegorical, which asserts that "the Stone will appear on the Day of Judgement (Qiyamah) with eyes to see and a tongue to speak, and give evidence in favour of all who kissed it in true devotion, but speak out against whoever indulged in gossip or profane conversations during his circumambulation of the Kaaba".[58]

Scientific origins

The nature of the Black Stone has been much debated. It has been described variously as basalt stone, an agate, a piece of natural glass or – most popularly – a stony meteorite. Paul Partsch, the curator of the Austro-Hungarian imperial collection of minerals, published the first comprehensive analysis of the Black Stone in 1857 in which he favoured a meteoritic origin for the Stone.[60] Robert Dietz and John McHone proposed in 1974 that the Black Stone was actually an agate, judging from its physical attributes and a report by an Arab geologist that the Stone contained clearly discernible diffusion banding characteristic of agates.[2]

A significant clue to its nature is provided by an account of the Stone's recovery in 951 CE after it had been stolen 21 years earlier; according to a chronicler, the Stone was identified by its ability to float in water. If this account is accurate, it would rule out the Black Stone being an agate, a basalt lava, or a stony meteorite, though it would be compatible with it being glass or pumice.[7]

Elsebeth Thomsen of the University of Copenhagen proposed a different hypothesis in 1980. She suggested that the Black Stone may be a glass fragment or impactite from the impact of a fragmented meteorite that fell 6,000 years ago at Wabar,[61] a site in the Rub' al Khali desert 1,100 km east of Mecca. A 2004 scientific analysis of the Wabar site suggests that the impact event happened much more recently than first thought and might have occurred within the last 200–300 years.[62]

The meteoritic hypothesis is viewed by geologists as doubtful. The British Natural History Museum suggests that it may be a pseudometeorite, in other words a terrestrial rock mistakenly attributed to a meteoritic origin.[63]

The Black Stone has never been analysed with modern scientific techniques and its origins remain the subject of speculation.[64]

See also

References

Citations

- Golia, Maria (2015). Meteorite: Nature and Culture. Reaktion Books. ISBN 978-1780235479.

Bibliography

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Black Stone. |

- Grunebaum, G. E. von (1970). Classical Islam: A History 600 A.D.–1258 A.D.. Aldine Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-202-15016-1

- Sheikh Safi-ur-Rahman al-Mubarkpuri (2002). Ar-Raheeq Al-Makhtum (The Sealed Nectar): Biography of the Prophet. Dar-us-Salam Publications. ISBN 1-59144-071-8.

- Elliott, Jeri (1992). Your Door to Arabia. ISBN 0-473-01546-3.

- Mohamed, Mamdouh N. (1996). Hajj to Umrah: From A to Z. Amana Publications. ISBN 0-915957-54-X.

- Time-Life Books (1988). Time Frame AD 600–800: The March of Islam, ISBN 0-8094-6420-9.

No comments:

Post a Comment