"The Atacama Desert is the driest nonpolar desert in the world, as well as the only true desert to receive less precipitation than the polar deserts and the largest fog desert in the world."

The Atacama Desert is the real beach front property for the new mathematics that makes arithmetic the metric. As cycle is to system and constellation to star it remains to the galaxy to explain an earth beach. To simplify at complicate a beach to clam for the evolution of unit as the sand to shore in the suffix. Treating that as what is a mass to land the complication remained and the weather introduction explains.

To group the mythology and the Weather Channel as the unit to electrical output will reverberate to tone, a noise, a sound, a vortex, the basis of the Peruvian weather at the above the bottom of the oceans massive wave to salt the sea and answer the punctuation needed to beacon a swell.

The driest place on earth would indeed provision such mathematics as that is the ocean that can be studied to understand the vortex as a product of arithmetic at evolution not creation. The biblical prowess is still answered with the flood and drain to provision of impact of a cyclone to the where is the land at mass, a real breeze to the driest plateau has invited the genesis with a calendar on planet to envelope this letter to land mass at the fall of unit bringing the mud as an exposure to earth.

To these basic matter(s) as math to arithmetic equaling equator the point to measure would compass to stories on both products to understand date, map and not chart. New Math: Product the Mayan calendar and the katun ( Baktun ) becomes the wheel to spoke, a real wagon provision to only understand tree and not to circle it.

Regarding the “Flat world” as in our history the letter would have had to been blocked by walls and the water to salt the sting bringing animal nature to explain?

Dry is the ground and Vortex the word!!

To product the calendar, at the base the structure to study the probability of clam to land and shore to sand is the date and that adds more than the apple as the apple is standard to the quote and or saying: “Doesn’t fall far from the tree”. These placements deliver the ocean at the swerve to why salt and the makings of salt to sea remain on the oceans foot; a real bravo. To continue with these basic matter(s) as the math to arithmetic, it is the turn to understand salted air.

Polar vortex

A circumpolar vortex, or simply polar vortex, is a large region of cold, rotating air that encircles both of Earth's polar regions. Polar vortices also exist on other rotating, low-obliquity planetary bodies.[1] The term polar vortex can be used to describe two distinct phenomena; the stratospheric polar vortex, and the tropospheric polar vortex. The stratospheric and tropospheric polar vortices both rotate in the direction of the Earth's spin, but they are distinct phenomena that have different sizes, structures, seasonal cycles, and impacts on weather.

The stratospheric polar vortex is an area of high-speed, cyclonically rotating winds around 15 km to 50 km high, poleward of 50°, and is strongest in winter. It forms in Autumn when Arctic or Antarctic temperatures cool rapidly as the polar night begins. The increased temperature difference between the pole and the tropics causes strong winds and the Coriolis effect causes the vortex to spin up. The stratospheric polar vortex breaks down in Spring as the polar night ends. A sudden stratospheric warming (SSW) is an event that occurs when the stratospheric vortex breaks down during winter, and can have significant impacts on surface weather.[citation needed]

The tropospheric polar vortex is often defined as the area poleward of the tropospheric jet stream. The equatorward edge is around 40° to 50°, and it extends from the surface up to around 10 km to 15 km. Its yearly cycle differs from the stratospheric vortex because the tropospheric vortex exists all year, but is similar to the stratospheric vortex since it is also strongest in winter when the polar regions are coldest.

The tropospheric polar vortex was first described as early as 1853.[2] The stratospheric vortex's SSWs were discovered in 1952 with radiosonde observations at altitudes higher than 20 km.[3] The tropospheric polar vortex was mentioned frequently in the news and weather media in the cold North American winter of 2013–2014, popularizing the term as an explanation of very cold temperatures.[4] The tropospheric vortex increased in public visibility in 2021 as a result of extreme frigid temperatures in the central United States, with some sources linking its effects to climate change.[5]

Ozone depletion occurs within the polar vortices – particularly over the Southern Hemisphere – reaching a maximum depletion in the spring.

Arctic and Antarctic vortices

Northern hemisphere

When the tropospheric vortex of the Arctic is strong, it is well defined, there is a single vortex with a jet stream that is "well constrained" near the polar front, and the Arctic air is well contained. When the northern tropospheric vortex weakens, which it generally does, it will break into two or more smaller vortices, the strongest of which are near Baffin Island, Canada, and the other over northeast Siberia. When it is very weak, the flow of Arctic air becomes more disorganized, and masses of cold Arctic air can push equatorward, bringing with them a rapid and sharp temperature drop.[6]

A deep freeze that gripped much of the United States and Canada in late January 2019 has been blamed on a "polar vortex". This is not the scientifically correct use of the term polar vortex, but instead is referring to outbreaks of cold Arctic air caused by a weakened polar vortex. The US National Weather Service warned that frostbite is possible within just 10 minutes of being outside in such extreme temperatures, and hundreds of schools, colleges and universities in the affected areas were closed. Around 21 people died in US due to severe frostbite.[7][8] States within the midwest region of the United States had windchills just above -50 °F (-45 °C). The Polar vortex is also thought to have had effects in Europe. For example, the 2013–14 United Kingdom winter floods were blamed on the Polar vortex bringing severe cold in the United States and Canada.[9] Similarly, the severe cold in the United Kingdom in the winters of 2009/10 and 2010/11 were also blamed on the Polar vortex.[10]

Southern hemisphere

The Antarctic vortex of the Southern Hemisphere is a single low-pressure zone that is found near the edge of the Ross ice shelf, near 160 west longitude. When the polar vortex is strong, the mid-latitude Westerlies (winds at the surface level between 30° and 60° latitude from the west) increase in strength and are persistent. When the polar vortex is weak, high-pressure zones of the mid-latitudes may push poleward, moving the polar vortex, jet stream, and polar front equatorward. The jet stream is seen to "buckle" and deviate south. This rapidly brings cold dry air into contact with the warm, moist air of the mid-latitudes, resulting in a rapid and dramatic change of weather known as a "cold snap".[11]

In Australia, the polar vortex, known there as a "polar blast" or "polar plunge", is a cold front that drags air from Antarctica which brings rain showers, snow (typically inland, with blizzards occurring in the highlands), gusty icy winds, and hail in the south-eastern parts of the country, such as in Victoria, Tasmania, the southeast coast of South Australia and the southern half of New South Wales (but only on the windward side of the Great Dividing Range, whereas the leeward side will be affected by foehn winds).[12][13]

Identification

The bases of the two polar vortices are located in the middle and upper troposphere and extend into the stratosphere. Beneath that lies a large mass of cold, dense Arctic air. The interface between the cold dry air mass of the pole and the warm moist air mass farther south defines the location of the polar front. The polar front is centered, roughly at 60° latitude. A polar vortex strengthens in the winter and weakens in the summer because of its dependence on the temperature difference between the equator and the poles.[14]

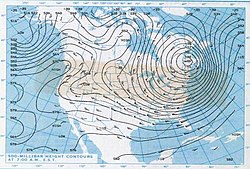

Polar cyclones are low-pressure zones embedded within the polar air masses, and exist year-round. The stratospheric polar vortex develops at latitudes above the subtropical jet stream.[15] Horizontally, most polar vortices have a radius of less than 1,000 kilometres (620 mi).[16] Since polar vortices exist from the stratosphere downward into the mid-troposphere,[6] a variety of heights/pressure levels are used to mark its position. The 50 hPa pressure surface is most often used to identify its stratospheric location.[17] At the level of the tropopause, the extent of closed contours of potential temperature can be used to determine its strength. Others have used levels down to the 500 hPa pressure level (about 5,460 metres (17,910 ft) above sea level during the winter) to identify the polar vortex.[18]

Duration and strength

Polar vortices are weakest during summer and strongest during winter. Extratropical cyclones that migrate into higher latitudes when the polar vortex is weak can disrupt the single vortex creating smaller vortices (cold-core lows) within the polar air mass.[19] Those individual vortices can persist for more than a month.[16]

Volcanic eruptions in the tropics can lead to a stronger polar vortex during winter for as long as two years afterwards.[20] The strength and position of the polar vortex shapes the flow pattern in a broad area about it. An index which is used in the northern hemisphere to gauge its magnitude is the Arctic oscillation.[21]

When the Arctic vortex is at its strongest, there is a single vortex, but normally, the Arctic vortex is elongated in shape, with two cyclone centers, one over Baffin Island in Canada and the other over northeast Siberia. When the Arctic pattern is at its weakest, subtropic air masses can intrude poleward causing the Arctic air masses to move equatorward, as during the Winter 1985 Arctic outbreak.[22] The Antarctic polar vortex is more pronounced and persistent than the Arctic one. In the Arctic the distribution of land masses at high latitudes in the Northern Hemisphere gives rise to Rossby waves which contribute to the breakdown of the polar vortex, whereas in the Southern Hemisphere the vortex is less disturbed. The breakdown of the polar vortex is an extreme event known as a sudden stratospheric warming, here the vortex completely breaks down and an associated warming of 30–50 °C (54–90 °F)[clarification needed] over a few days can occur.

The waxing and waning of the polar vortex is driven by the movement of mass and the transfer of heat in the polar region. In the autumn, the circumpolar winds increase in speed and the polar vortex rises into the stratosphere. The result is that the polar air forms a coherent rotating air mass: the polar vortex. As winter approaches, the vortex core cools, the winds decrease, and the vortex energy declines. Once late winter and early spring approach the vortex is at its weakest. As a result, during late winter, large fragments of the vortex air can be diverted into lower latitudes by stronger weather systems intruding from those latitudes. In the lowest level of the stratosphere, strong potential vorticity gradients remain, and the majority of that air remains confined within the polar air mass into December in the Southern Hemisphere and April in the Northern Hemisphere, well after the breakup of the vortex in the mid-stratosphere.[23]

The breakup of the northern polar vortex occurs between mid March to mid May. This event signifies the transition from winter to spring, and has impacts on the hydrological cycle, growing seasons of vegetation, and overall ecosystem productivity. The timing of the transition also influences changes in sea ice, ozone, air temperature, and cloudiness. Early and late polar breakup episodes have occurred, due to variations in the stratospheric flow structure and upward spreading of planetary waves from the troposphere.[clarification needed] As a result of increased waves into the vortex, the vortex experiences more rapid warming than normal, resulting in an earlier breakup and spring. When the breakup comes early, it is characterized by[clarification needed] with persistent of remnants of the vortex. When the breakup is late, the remnants dissipate rapidly. When the breakup is early, there is one warming period from late February to middle March. When the breakup is late, there are two warming periods, one January, and one in March. Zonal mean temperature, wind, and geopotential height exert varying deviations from their normal values before and after early breakups, while the deviations remain constant before and after late breakups. Scientists are connecting a delay in the Arctic vortex breakup with a reduction of planetary wave activities, few stratospheric sudden warming events, and depletion of ozone.[24][25][clarification needed]

Sudden stratospheric warming events are associated with weaker polar vortices. This warming of stratospheric air can reverse the circulation in the Arctic Polar Vortex from counter-clockwise to clockwise.[26] These changes aloft force changes in the troposphere below.[27] An example of an effect on the troposphere is the change in speed of the Atlantic Ocean circulation pattern. A soft spot just south of Greenland is where the initial step of downwelling occurs, nicknamed the "Achilles Heel of the North Atlantic". Small amounts of heating or cooling traveling from the polar vortex can trigger or delay downwelling, altering the Gulf Stream Current of the Atlantic, and the speed of other ocean currents. Since all other oceans depend on the Atlantic Ocean's movement of heat energy, climates across the planet can be dramatically affected. The weakening or strengthening of the polar vortex can alter the sea circulation more than a mile beneath the waves.[28] Strengthening storm systems within the troposphere that cool the poles, intensify the polar vortex. La Niña–related climate anomalies significantly strengthen the polar vortex.[29] Intensification of the polar vortex produces changes in relative humidity as downward intrusions of dry, stratospheric air enter the vortex core. With a strengthening of the vortex comes a longwave cooling due to a decrease in water vapor concentration near the vortex. The decreased water content is a result of a lower tropopause within the vortex, which places dry stratospheric air above moist tropospheric air.[30] Instability is caused when the vortex tube, the line of concentrated vorticity, is displaced. When this occurs, the vortex rings become more unstable and prone to shifting by planetary waves. The planetary wave activity in both hemispheres varies year-to-year, producing a corresponding response in the strength and temperature of the polar vortex.[31] The number of waves around the perimeter of the vortex are related to the core size; as the vortex core decreases, the number of waves increase.[32]

The degree of the mixing of polar and mid-latitude air depends on the evolution and position of the polar night jet. In general, the mixing is less inside the vortex than outside. Mixing occurs with unstable planetary waves that are characteristic of the middle and upper stratosphere in winter. Prior to vortex breakdown, there is little transport of air out of the Arctic Polar Vortex due to strong barriers above 420 km (261 miles). The polar night jet which exists below this, is weak in the early winter. As a result, it does not deviate any descending polar air, which then mixes with air in the mid-latitudes. In the late winter, air parcels do not descend as much, reducing mixing.[33] After the vortex is broken up, the ex-vortex air is dispersed into the middle latitudes within a month.[34]

Sometimes, a mass of the polar vortex breaks off before the end of the final warming period. If large enough, the piece can move into Canada and the Midwestern, Central, Southern, and Northeastern United States. This diversion of the polar vortex can occur due to the displacement of the polar jet stream; for example, the significant northwestward direction of the polar jet stream in the western part of the United States during the winters of 2013–2014, and 2014–2015. This caused warm, dry conditions in the west, and cold, snowy conditions in the north-central and northeast.[35] Occasionally, the high-pressure air mass, called the Greenland Block, can cause the polar vortex to divert to the south, rather than follow its normal path over the North Atlantic.[36]

Climate change

A study in 2001 found that stratospheric circulation can have anomalous effects on weather regimes.[37] In the same year, researchers found a statistical correlation between weak polar vortex and outbreaks of severe cold in the Northern Hemisphere.[38][39] In later years, scientists identified interactions with Arctic sea ice decline, reduced snow cover, evapotranspiration patterns, NAO anomalies or weather anomalies which are linked to the polar vortex and jet stream configuration.[37][39][40][41][42][43][44][45] However, because the specific observations are considered short-term observations (starting c. 13 years ago) there is considerable uncertainty in the conclusions. Climatology observations require several decades to definitively distinguish natural variability from climate trends.[46]

The general assumption is that reduced snow cover and sea ice reflect less sunlight and therefore evaporation and transpiration increases, which in turn alters the pressure and temperature gradient of the polar vortex, causing it to weaken or collapse. This becomes apparent when the jet stream amplitude increases (meanders) over the northern hemisphere, causing Rossby waves to propagate farther to the south or north, which in turn transports warmer air to the north pole and polar air into lower latitudes. The jet stream amplitude increases with a weaker polar vortex, hence increases the chance for weather systems to become blocked. A blocking event in 2012 emerged when a high-pressure over Greenland steered Hurricane Sandy into the northern Mid-Atlantic states.[47]

Ozone depletion

The chemistry of the Antarctic polar vortex has created severe ozone depletion. The nitric acid in polar stratospheric clouds reacts with chlorofluorocarbons to form chlorine, which catalyzes the photochemical destruction of ozone.[48] Chlorine concentrations build up during the polar winter, and the consequent ozone destruction is greatest when the sunlight returns in spring.[49] These clouds can only form at temperatures below about −80 °C (−112 °F).

Since there is greater air exchange between the Arctic and the mid-latitudes, ozone depletion at the north pole is much less severe than at the south.[50] Accordingly, the seasonal reduction of ozone levels over the Arctic is usually characterized as an "ozone dent", whereas the more severe ozone depletion over the Antarctic is considered an "ozone hole". That said, chemical ozone destruction in the 2011 Arctic polar vortex attained, for the first time, a level clearly identifiable as an Arctic "ozone hole".[51]

Outside Earth

Other astronomical bodies are also known to have polar vortices, including Venus (double vortex – that is, two polar vortices at a pole),[52] Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and Saturn's moon Titan.

Saturn's south pole is the only known hot polar vortex in the solar system.[53]

See also

- Polar amplification

- Saturn's hexagon – a persisting hexagonal cloud pattern around the north pole of Saturn

- Windward Performance Perlan II – will be used to study the northern polar vortex

References

- "Saturn's Bull's-Eye Marks Its Hot Spot". NASA. 2005. Retrieved January 8, 2014.

Further reading

- "The science behind the polar vortex". NOAA.gov (NASA). 29 Jan 2019. Retrieved 31 Jan 2019.

- "What Is a Polar Vortex?". NOAA SciJinks.gov (NASA). Retrieved 31 Jan 2019.

- "What is the Polar Vortex?". US National Weather Service. Retrieved 31 Jan 2019.

- Nash, Eric R.; Newman, Paul A.; Rosenfield, Joan E.; Schoeberl, Mark R. (1996). "An objective determination of the polar vortex using Ertel's potential vorticity". Journal of Geophysical Research. 101 (D5): 9471–78. Bibcode:1996JGR...101.9471N. doi:10.1029/96JD00066.

- Butchart, Neal; Remsberg, Ellis E. (1986). "The Area of the Stratospheric Polar Vortex as a Diagnostic for Tracer Transport on an Isentropic Surface". Journal of the Atmospheric Sciences. 43 (13): 1319–1339. Bibcode:1986JAtS...43.1319B. doi:10.1175/1520-0469(1986)043<1319:TAOTSP>2.0.CO;2.

- Schoeberl, Mark R.; Lait, Leslie R.; Newman, Paul A.; Rosenfield, Joan E. (1992). "The structure of the polar vortex". Journal of Geophysical Research. 97 (D8): 7859–82. Bibcode:1992JGR....97.7859S. doi:10.1029/91JD02168.

- Coy, Lawrence; Nash, Eric R.; Newman, Paul A. (1997). "Meteorology of the polar vortex: Spring 1997". Geophysical Research Letters. 24 (22): 2693–96. Bibcode:1997GeoRL..24.2693C. doi:10.1029/97GL52832.

- Schoeberl, M.R.; Hartmann, D.L. (1991). "The Dynamics of the Stratospheric Polar Vortex and Its Relation to Springtime Ozone Depletions". Science. 251 (4989): 46–52. Bibcode:1991Sci...251...46S. doi:10.1126/science.251.4989.46. PMID 17778602.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Polar vortex. |

- "Current map of arctic winds and temperatures at the 10 hPa level".

- "Current map of arctic winds and temperatures at the 70 hPa level".

- "Current map of arctic winds and temperatures at the 250 hPa level".

- "Current map of arctic winds and temperatures at the 500 hPa level".

- "Current map of antarctic winds and temperatures at the 10 hPa level".

- "Current map of antarctic winds and temperatures at the 70 hPa level".

- "Current map of antarctic winds and temperatures at the 250 hPa level".

- "Current map of antarctic winds and temperatures at the 500 hPa level".

Languages

Kʼatun

A kʼatun (/ˈkɑːtuːn/,[1] Mayan pronunciation: [kʼaˈtun]) is a unit of time in the Maya calendar equal to 20 tuns or 7200 days, equivalent to 19.713 tropical years. It is the second digit on the normal Maya long count date. For example, in the Maya Long Count date 12.19.13.15.12 (December 5, 2006), the number 19 is the kʼatun.

The end of a kʼatun was marked by numerous ceremonies and at Tikal the construction of large twin pyramid complexes to host them.[2] The kʼatun was also used to reckon the age of rulers. Those who lived to see four (or five) kʼatuns would take the title 4-(or 5-)kʼatun ruler.[3] In the Postclassic period when the full Long Count gave way to the Short Count, the Maya continued to keep a reckoning of kʼatuns, differentiating them by the Calendar Round date on which they began. Each kʼatun had its own set of prophecies and associations.[4]

Notes

- Schele and Freidel (1990, p.400).

References

- Coe, Michael D. (1992). Breaking the Maya Code. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05061-9. OCLC 26605966.

- Martin, Simon; Nikolai Grube (2000). Chronicle of the Maya Kings and Queens: Deciphering the Dynasties of the Ancient Maya. London and New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-05103-8. OCLC 47358325.

- Schele, Linda; David Freidel (1990). A Forest of Kings: The Untold Story of the Ancient Maya. New York: William Morrow. ISBN 0-688-07456-1. OCLC 21295769.

Languages

Popol Vuh

Popol Vuh (also Popol Wuj or Popul Vuh or Pop Vuj)[1][2] is a text recounting the mythology and history of the Kʼicheʼ people, one of the Maya peoples, who inhabit Guatemala, Mexican Chiapas, Campeche, Yucatan and Quintana Roo states, areas of Belize and Honduras.

The Popol Vuh is a foundational sacred narrative of the Kʼicheʼ people from long before the Spanish conquest of Mexico.[3] It includes the Mayan creation myth, the exploits of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué,[4] and a chronicle of the Kʼicheʼ people.

The name "Popol Vuh" translates as "Book of the Community", "Book of Counsel", or more literally as "Book of the People".[5] It was originally preserved through oral tradition[6] until approximately 1550, when it was recorded in writing.[7] The documentation of the Popol Vuh is credited to the 18th-century Spanish Dominican friar Francisco Ximénez, who prepared a manuscript with a transcription in Kʼicheʼ and parallel columns with translations into Spanish.[6][8]

Like the Chilam Balam and similar texts, the Popol Vuh is of particular importance given the scarcity of early accounts dealing with Mesoamerican mythologies. After the Spanish conquest, missionaries and colonists destroyed many documents.[9]

History

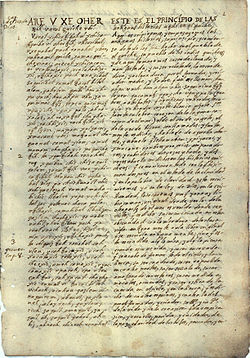

Father Ximénez's manuscript

In 1701, Father Ximénez came to Santo Tomás Chichicastenango (also known as Santo Tomás Chuilá). This town was in the Quiché territory and is likely where Father Ximénez first recorded the work.[10] Ximénez transcribed and translated the account, setting up parallel Kʼicheʼ and Spanish language columns in his manuscript (he represented the Kʼicheʼ language phonetically with Latin and Parra characters). In or around 1714, Ximénez incorporated the Spanish content in book one, chapters 2–21 of his Historia de la provincia de San Vicente de Chiapa y Guatemala de la orden de predicadores. Ximénez's manuscripts were held posthumously by the Dominican Order until General Francisco Morazán expelled the clerics from Guatemala in 1829–30. At that time the Order's documents were taken over largely by the Universidad de San Carlos.

From 1852 to 1855, Moritz Wagner and Carl Scherzer traveled in Central America, arriving in Guatemala City in early May 1854.[11] Scherzer found Ximénez's writings in the university library, noting that there was one particular item "del mayor interés" ('of the greatest interest'). With assistance from the Guatemalan historian and archivist Juan Gavarrete, Scherzer copied (or had a copy made of) the Spanish content from the last half of the manuscript, which he published upon his return to Europe.[12] In 1855, French Abbot Charles Étienne Brasseur de Bourbourg also came across Ximénez's manuscript in the university library. However, whereas Scherzer copied the manuscript, Brasseur apparently stole the university's volume and took it back to France.[13] After Brasseur's death in 1874, the Mexico-Guatémalienne collection containing Popol Vuh passed to Alphonse Pinart, through whom it was sold to Edward E. Ayer. In 1897, Ayer decided to donate his 17,000 pieces to The Newberry Library in Chicago, a project that was not completed until 1911. Father Ximénez's transcription-translation of Popol Vuh was among Ayer's donated items.

Father Ximénez's manuscript sank into obscurity until Adrián Recinos rediscovered it at the Newberry in 1941. Recinos is generally credited with finding the manuscript and publishing the first direct edition since Scherzer. But Munro Edmonson and Carlos López attribute the first rediscovery to Walter Lehmann in 1928.[14] Experts Allen Christenson, Néstor Quiroa, Rosa Helena Chinchilla Mazariegos, John Woodruff, and Carlos López all consider the Newberry volume to be Ximénez's one and only "original."

Father Ximénez's source

It is generally believed that Ximénez borrowed a phonetic manuscript from a parishioner for his source, although Néstor Quiroa points out that "such a manuscript has never been found, and thus Ximenez's work represents the only source for scholarly studies."[15] This document would have been a phonetic rendering of an oral recitation performed in or around Santa Cruz del Quiché shortly following Pedro de Alvarado's 1524 conquest. By comparing the genealogy at the end of Popol Vuh with dated colonial records, Adrián Recinos and Dennis Tedlock suggest a date between 1554 and 1558.[16] But to the extent that the text speaks of a "written" document, Woodruff cautions that "critics appear to have taken the text of the first folio recto too much at face value in drawing conclusions about Popol Vuh's survival."[17] If there was an early post-conquest document, one theory (first proposed by Rudolf Schuller) ascribes the phonetic authorship to Diego Reynoso, one of the signatories of the Título de Totonicapán.[18] Another possible author could have been Don Cristóbal Velasco, who, also in Titulo de Totonicapán, is listed as "Nim Chokoh Cavec" ('Great Steward of the Kaweq').[19][20] In either case, the colonial presence is clear in Popol Vuh's preamble: "This we shall write now under the Law of God and Christianity; we shall bring it to light because now the Popol Vuh, as it is called, cannot be seen any more, in which was clearly seen the coming from the other side of the sea and the narration of our obscurity, and our life was clearly seen."[21] Accordingly, the need to "preserve" the content presupposes an imminent disappearance of the content, and therefore, Edmonson theorized a pre-conquest glyphic codex. No evidence of such a codex has yet been found.

A minority, however, disputes the existence of pre-Ximénez texts on the same basis that is used to argue their existence. Both positions are based on two statements by Ximénez. The first of these comes from Historia de la provincia where Ximénez writes that he found various texts during his curacy of Santo Tomás Chichicastenango that were guarded with such secrecy "that not even a trace of it was revealed among the elder ministers" although "almost all of them have it memorized."[22] The second passage used to argue pre-Ximénez texts comes from Ximénez's addendum to Popol Vuh. There he states that many of the natives' practices can be "seen in a book that they have, something like a prophecy, from the beginning of their [pre-Christian] days, where they have all the months and signs corresponding to each day, one of which I have in my possession."[23] Scherzer explains in a footnote that what Ximénez is referencing "is only a secret calendar" and that he himself had "found this rustic calendar previously in various indigenous towns in the Guatemalan highlands" during his travels with Wagner.[24] This presents a contradiction because the item which Ximénez has in his possession is not Popol Vuh, and a carefully guarded item is not likely to have been easily available to Ximénez. Apart from this, Woodruff surmises that because "Ximenez never discloses his source, instead inviting readers to infer what they wish [. . .], it is plausible that there was no such alphabetic redaction among the Indians. The implied alternative is that he or another missionary made the first written text from an oral recitation."[25]

Story of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué

Many versions of the legend of the Hero Twins Hunahpú and Xbalanqué circulated through the Mayan peoples[citation needed], but the story that survives was preserved by the Dominican priest Francisco Ximénez[6] who translated the document between 1700 and 1715.[26] Maya deities in the Post-Classic codices differ from the earlier versions described in the Early Classic period. In Mayan mythology Hunahpú and Xbalanqué are the second pair of twins out of three, preceded by Hun-Hunahpú and his brother Vucub-Hunahpú, and precursors to the third pair of twins, Hun Batz and Hun Chuen. In the Popol Vuh, the first set of twins, Hun-Hunahpú and Vucub-Hanahpú were invited to the Mayan Underworld, Xibalba, to play a ballgame with the Xibalban lords. In the Underworld the twins faced many trials filled with trickery; eventually they fail and are put to death. The Hero Twins, Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, are magically conceived after the death of their father, Hun-Hunahpú, and in time they return to Xibalba to avenge the deaths of their father and uncle by defeating the Lords of the Underworld.

Structure

Popol Vuh encompasses a range of subjects that includes creation, ancestry, history, and cosmology. There are no content divisions in the Newberry Library's holograph, but popular editions have adopted the organization imposed by Brasseur de Bourbourg in 1861 in order to facilitate comparative studies.[27] Though some variation has been tested by Dennis Tedlock and Allen Christenson, editions typically take the following form:

Vertical lines indicate descent

Horizontal lines indicate siblings

Double lines indicate marriage

This article or section possibly contains synthesis of material which does not verifiably mention or relate to the main topic. (February 2019) |

Preamble

- Introduction to the piece that introduces Xpiyacoc and Xmucane, the purpose for writing the Popol Vuh, and the measuring of the earth.[28]

Book One

- Account of the creation of living beings. Animals were created first, followed by humans. The first humans were made of earth and mud, but soaked up water and dissolved. The second humans were created from wood, but they were washed away in a flood.[29]

- Vucub-Caquix ascends.[29]

Book Two

- The Hero Twins plan to kill Vucub-Caquix and his sons, Zipacna and Cabracan.[29]

- They succeed, "restoring order and balance to the world."[29]

Book Three

- The father and uncle of The Hero Twins, Hun Hunahpu and Vucub Hunahpu, sons of Xmucane and Xpiacoc, are murdered at a ball game in Xibalba.[29]

- Hun Hunahpu's head is placed in a calabash tree, where it spits in the hand of Xquiq, impregnating her.[29]

- She leaves the underworld to be with her mother-in-law, Xmucane.[29]

- Her sons then challenge the Lords who killed their father and uncle, succeeding and becoming the sun and the moon.[29]

Book Four

- Humans are successfully created from maize.[29]

- The gods give them morality in order to keep them loyal.[29]

- Later, they give the humans wives to make them content.[29]

- This book also describes the movement of the Kʼicheʼ and includes the introduction of Gucumatz.[29]

Excerpts

A visual comparison of two sections of the Popol Vuh are presented below and include the original Kʼiche, literal English translation, and modern English translation as shown by Allen Christenson.[30][31][32]

"Preamble"

| Original Kʼiche | Literal English Translation | Modern English Translation |

|---|---|---|

AREʼ U XEʼ OJER TZIJ,

Xchiqatikibʼaʼ wi ojer tzij, U tikaribʼal, U xeʼnabʼal puch, Ronojel xbʼan pa

|

THIS ITS ROOT ANCIENT WORD,

We shall plant ancient word, Its planting, Its root-beginning as well, Everything done in

|

THIS IS THE BEGINNING OF THE ANCIENT TRADITIONS

We shall begin to tell the ancient stories of the beginning, the origin of all that was done in

|

"The Primordial World"

| Original Kʼiche | Literal English Translation | Modern English Translation |

|---|---|---|

| AREʼ U TZIJOXIK Waʼe. Kʼa katzʼininoq, Katzʼinonik, |

THIS ITS ACCOUNT These things. Still be it silent, It is silent, Still it is hushed, |

THIS IS THE ACCOUNT of when all is still silent All is silent |

Modern history

Modern editions

Since Brasseur's and Scherzer's first editions, the Popol Vuh has been translated into many other languages besides its original Kʼicheʼ.[37] The Spanish edition by Adrián Recinos is still a major reference, as is Recino's English translation by Delia Goetz. Other English translations[38] include those of Victor Montejo,[39] Munro Edmonson (1985), and Dennis Tedlock (1985, 1996).[40] Tedlock's version is notable because it builds on commentary and interpretation by a modern Kʼicheʼ daykeeper, Andrés Xiloj. Augustín Estrada Monroy published a facsimile edition in the 1970s and Ohio State University has a digital version and transcription online. Modern translations and transcriptions of the Kʼicheʼ text have been published by, among others, Sam Colop (1999) and Allen J. Christenson (2004). In 2018, The New York Times named Michael Bazzett's new translation as one of the ten best books of poetry of 2018.[41] The tale of Hunahpu and Xbalanque has also been rendered as an hour-long animated film by Patricia Amlin.[42][43]

Contemporary culture

The Popol Vuh continues to be an important part in the belief system of many Kʼicheʼ.[citation needed] Although Catholicism is generally seen as the dominant religion, some believe that many natives practice a syncretic blend of Christian and indigenous beliefs. Some stories from the Popol Vuh continued to be told by modern Maya as folk legends; some stories recorded by anthropologists in the 20th century may preserve portions of the ancient tales in greater detail than the Ximénez manuscript.[citation needed] On August 22, 2012, the Popol Vuh was declared intangible cultural heritage of Guatemala by the Guatemalan Ministry of Culture.[44]

Reflections in Western culture

Since its rediscovery by Europeans in the nineteenth century, the Popol Vuh has attracted the attention of many creators of cultural works.

Mexican muralist Diego Rivera produced a series of watercolors in 1931 as illustrations for the book.

In 1934, the early avant-garde Franco-American composer Edgard Varèse wrote his Ecuatorial, a setting of words from the Popol Vuh for bass soloist and various instruments.

The planet of Camazotz in Madeleine L'Engle's A Wrinkle in Time (1962) is named for the bat-god of the hero-twins story.

In 1969 in Munich, Germany, keyboardist Florian Fricke—at the time ensconced in Mayan myth—formed a band named Popol Vuh with synth player Frank Fiedler and percussionist Holger Trulzsch. Their 1970 debut album, Affenstunde, reflected this spiritual connection. Another band by the same name, this one of Norwegian descent, formed around the same time, its name also inspired by the Kʼicheʼ writings.

The text was used by German film director Werner Herzog as extensive narration for the first chapter of his movie Fata Morgana (1971). Herzog and Florian Fricke were life long collaborators and friends.

The Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera began writing his symphonic work Popol Vuh in 1975, but neglected to complete the piece before his death in 1983.

The myths and legends included in Louis L'Amour's novel The Haunted Mesa (1987) are largely based on the Popol Vuh.

The Popol Vuh is referenced throughout Robert Rodriguez's television show From Dusk till Dawn: The Series (2014). In particular, the show's protagonists, the Gecko Brothers, Seth and Richie, are referred to as the embodiment of Hunahpú and Xbalanqué, the hero twins, from the Popol Vuh.

Antecedents in Maya iconography

Contemporary archaeologists (first of all Michael D. Coe) have found depictions of characters and episodes from Popol Vuh on Mayan ceramics and other art objects (e.g., the Hero Twins, Howler Monkey Gods, the shooting of Vucub-Caquix and, as many believe, the restoration of the Twins' dead father, Hun Hunahpu).[45] The accompanying sections of hieroglyphical text could thus, theoretically, relate to passages from the Popol Vuh. Richard D. Hansen found a stucco frieze depicting two floating figures that might be the Hero Twins[46][47][48][49] at the site of El Mirador.[50]

Following the Twin Hero narrative, mankind is fashioned from white and yellow corn, demonstrating the crop's transcendent importance in Maya culture. To the Maya of the Classic period, Hun Hunahpu may have represented the maize god. Although in the Popol Vuh his severed head is unequivocally stated to have become a calabash, some scholars believe the calabash to be interchangeable with a cacao pod or an ear of corn. In this line, decapitation and sacrifice correspond to harvesting corn and the sacrifices accompanying planting and harvesting.[51] Planting and harvesting also relate to Maya astronomy and calendar, since the cycles of the moon and sun determined the crop seasons.[52]

Notable Editions

- 1857. Scherzer, Carl, ed. (1857). Las historias del origen de los indios de esta provincia de Guatemala. Vienna: Carlos Gerold e hijo.

- 1861. Brasseur de Bourbourg; Charles Étienne (eds.). Popol vuh. Le livre sacré et les mythes de l'antiquité américaine, avec les livres héroïques et historiques des Quichés. Paris: Bertrand.

- 1944. Popol Vuh: das heilige Buch der Quiché-Indianer von Guatemala, nach einer wiedergefundenen alten Handschrift neu übers. und erlautert von Leonhard Schultze. Schultze Jena, Leonhard (trans.). Stuttgart, Germany: W. Kohlhammer. OCLC 2549190.

- 1947. Recinos, Adrián (ed.). Popol Vuh: las antiguas historias del Quiché. Mexico: Fondo de Cultura Económica.

- 1950. Goetz, Delia; Morley, Sylvanus Griswold (eds.). Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Ancient Quiché Maya By Adrián Recinos (1st ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

- 1971. Edmonson, Munro S. (ed.). The Book of Counsel: The Popol-Vuh of the Quiche Maya of Guatemala. Publ. no. 35. New Orleans: Middle American Research Institute, Tulane University. OCLC 658606.

- 1973. Estrada Monroy, Agustín (ed.). Popol Vuh: empiezan las historias del origen de los índios de esta provincia de Guatemala (Edición facsimilar ed.). Guatemala City: Editorial "José de Piñeda Ibarra". OCLC 1926769.

- 1985. Popol Vuh: the Definitive Edition of the Mayan Book of the Dawn of Life and the Glories of Gods and Kings, with commentary based on the ancient knowledge of the modern Quiché Maya. Tedlock, Dennis (translator). New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-671-45241-X. OCLC 11467786.

- 1999. Colop, Sam, ed. (1999). Popol Wuj: versión poética Kʼicheʼ. Quetzaltenango; Guatemala City: Proyecto de Educación Maya Bilingüe Intercultural; Editorial Cholsamaj. ISBN 99922-53-00-2. OCLC 43379466. (in K'iche')

- 2004. Popol Vuh: Literal Poetic Version: Translation and Transcription. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. March 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3841-1.

- 2007. Popol Vuh: The Sacred Book of the Maya. Christenson, Allen J. (trans.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. 2007. ISBN 978-0-8061-3839-8.

- 2007. Poopol Wuuj - Das heilige Buch des Rates der K´ichee´-Maya von Guatemala. Rohark, Jens (trans.). 2007. ISBN 978-3-939665-32-8.

- 2018. The Popol Vuh: A New Verse Translation. Bazzett, Michael (trans.). Seedbank Books. 2018. ISBN 978-1-5713-1468-0.

See also

Notes

- McKillop, 214.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Popol Vuh. |

| Wikisource has original text related to this article: |

- Popol Wuj Archives, sponsored by the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at The Ohio State University, Columbus, Ohio, and the Center for Latin American Studies at OSU.

- A facsimile of the earliest preserved manuscript, in Quiché and Spanish, hosted at The Ohio State University Libraries. Learn more about this project by reading "Decolonial Information Practices: Repatriating and Stewarding the Popol Vuh Online."

- de los Monteros, Pamela Espinosa (2019-10-25). "Decolonial Information Practices: Repatriating and Stewarding the Popol Vuh Online". Preservation, Digital Technology & Culture. 48 (3–4): 107–119. doi:10.1515/pdtc-2019-0009. ISSN 2195-2965.

- The original Quiché text with line-by-line English translation Allen J. Christenson edition

- An English translation by Allen J. Christenson.

- Text in English404 De pagina is niet gevonden Goetz-Morley translation after Recinos

- A link to sections of the animated depiction by Patricia Amlin.

- Creation (1931). From the Collections at the Library of Congress

Languages

No comments:

Post a Comment