Clue one to the research of the post tilted 'The Treasure' is to understand "Book of the Seven Seas" as not the ocean of tides and charts rather to hinge a doorway to a new threshold, the balance. This is the avenue of treasure to arm the shield and say that there is more to masse than pool or ocean. Bound for the Ages of bronze it is the water not the tank for from that the trough: Attention: The term "Apostolic See" would better serve, enter information book one here:

The Holy See,

also called the See of Rome,

is the jurisdiction of the Bishop of Rome,

known as the pope,

which includes the apostolic episcopal see of the Diocese of Rome with universal ecclesiastical ...

Peter Freuchen

Peter Freuchen | |

|---|---|

Freuchen in 1921 | |

| Born | Lorenz Peter Elfred Freuchen February 20, 1886 Nykøbing Falster, Denmark |

| Died | September 2, 1957 (aged 71) |

| Nationality | Danish |

| Known for | Arctic explorer, author, journalist, anthropologist. |

| Spouse(s) | Navarana (Mequpaluk) Magda Vang Lauridsen Dagmar Cohn |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Anthropologist |

Lorenz Peter Elfred Freuchen (February 20, 1886 – September 2, 1957) was a Danish explorer, author, journalist and anthropologist. He is notable for his role in Arctic exploration, namely the Thule Expeditions.

Personal life

Freuchen was born in Nykøbing Falster, Denmark, the son of Anne Petrine Frederikke (née Rasmussen; 1862–1945) and Lorentz Benzon Freuchen (1859–1927). His father was a businessman. Freuchen was baptized in the local church.[1] He attended the University of Copenhagen where for a time he studied medicine.[2]

Freuchen was married three times. He was first married in 1911 to Navarana Mequpaluk (d. 1921), an Inuk woman who died in the Spanish Flu epidemic after bearing two children (a boy named Mequsaq Avataq Igimaqssusuktoranguapaluk (1916 - c. 1962) and a girl named Pipaluk Jette Tukuminguaq Kasaluk Palika Hager (1918–1999)[3]). His second marriage was to Magdalene Vang Lauridsen (1881–1960), daughter of Johannes Peter Lauridsen (1847-1920), Danish businessman and director of Danmarks Nationalbank. The marriage started in 1924 and was dissolved in 1944. In 1945, he married Danish fashion illustrator, Dagmar Cohn (1907–1991).[4]

Freuchen's grandson, Peter Ittinuar, was the first Inuk in Canada to be elected as an MP, and represented the electoral district of Nunatsiaq in the House of Commons of Canada from 1979 to 1984.[5][6]

From 1926 to 1940, Freuchen owned the Danish island Enehoje on Nakskov Fjord. During this period he wrote several books and articles and entertained guests. Since 2000, the uninhabited island has been a part of Nakskov Vildtreservat, a wildlife reserve.[7][8] At this time, Freuchen became heavily invested in socialism and anti-fascism.[9]

Career

In 1906, he went on his first expedition to Greenland as a member of the Denmark expedition. Between 1910 and 1924, he undertook several expeditions, often with the noted Polar explorer Knud Rasmussen. He worked with Rasmussen in crossing the Greenland ice sheet. He spent many years in Thule, Greenland, living with the Polar Inuit. In 1935, Freuchen visited South Africa, and by the end of the decade, he had travelled to Siberia.[10][11]

In 1910, Knud Rasmussen and Peter Freuchen established the Thule Trading Station at Cape York (Uummannaq), Greenland, as a trading base. The name Thule was chosen because it was the most northerly trading post in the world, literally the "Ultima Thule".[12] Thule Trading Station became the home base for a series of seven expeditions, known as the Thule Expeditions, between 1912 and 1933.

The First Thule Expedition (1912, Rasmussen and Freuchen) aimed to test Robert Peary's claim that a channel divided Peary Land from Greenland. They proved this was not the case in a 1,000 km (620 mi) journey across the inland ice that almost killed them.[13] Clements Markham, president of the Royal Geographical Society, called the journey the "finest ever performed by dogs."[14] Freuchen wrote personal accounts of this journey (and others) in Vagrant Viking (1953) and I Sailed with Rasmussen (1958). He states in Vagrant Viking that only one other dogsled trip across Greenland was ever successful. When he got stuck under an avalanche, he claims to have used his own feces to fashion a dagger with which he freed himself.[15]

While in Denmark, Freuchen and Rasmussen held a series of lectures about their expeditions and the Inuit culture.

Freuchen's first wife, Mekupaluk, who took the name Navarana, accompanied him on several expeditions. When she died he wanted her buried in the old church graveyard in Upernavik. The church refused to perform the burial, because Navarana was not baptized, so Freuchen buried her himself. Knud Rasmussen later used the name Navarana for the lead role in the movie Palos Brudefærd which was filmed in East Greenland in 1933. Freuchen strongly criticized the Christian church which sent missionaries among the Inuit without understanding their culture and traditions.

When Freuchen returned to Denmark in the 1920s, he joined the Social Democrats and contributed with articles in the newspaper Politiken. From 1926 to 1932 he served as the editor-in-chief of a magazine, Ude og Hjemme, owned by the family of his second wife.[16] He was also the leader of a movie company.

In 1932, Freuchen returned to Greenland. This time the expedition was financed by the American Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer film-studios.

He was also employed by the film industry as a consultant and scriptwriter, specializing in Arctic-related scripts, most notably MGM's Oscar-winning Eskimo/Mala The Magnificent starring Ray Mala, and featuring Freuchen as Ship Captain. In 1956, he won $64,000 on The $64,000 Question, an American TV quiz-show on the subject "The Seven Seas".[3]

In 1938, he founded The Adventurer's Club (Danish: Eventyrernes Klub), which still exists. They later honored his memory by planting an oak tree and creating an Eskimo cairn near the place where he left Denmark for Greenland in 1906. It is situated east of Langeliniebroen in central Copenhagen and not far from the statue of The Little Mermaid.

During World War II, Freuchen was actively involved with the Danish resistance movement against the occupation by Nazi Germany despite having lost a leg to frostbite in 1926.[17] He openly claimed to be Jewish whenever he witnessed anti-semitism.[18][19] Freuchen was imprisoned by the Germans, and was sentenced to death, but he managed to escape and flee to Sweden. In 1945 he married Danish-Jewish designer Dagmar Freuchen-Gale.

As he related in Vagrant Viking, he was friends with the royal families of Scandinavia and other countries, and his movie work in New York City and Hollywood brought him into the 'royalty' of moving pictures and the political world of Washington, D.C.

Later years

Freuchen and his wife Dagmar lived in New York City, and maintained a second home in Noank, Connecticut.

The preface of his last work, Book of the Seven Seas, is dated August 30, 1957, in Noank.[17] He died of a heart attack three days later at the Elmendorf Air Force Base in Anchorage, Alaska. After his death, his ashes were scattered on the famous table-shaped Mount Dundas outside of Thule.

Honours and awards

- Member, Royal Danish Geographical Society

- Fellow, American Geographical Society.[10]

- 1921 - Hans Egede Medal from the Royal Danish Geographical Society [20]

Freuchen Land in Greenland was named after him and Navarana Fjord was named after his first wife.

Literary prizes

- 1938 – Sophus Michaëlis' Legat[21]

- 1954 – Herman Bangs Mindelegat[22]

- 1955 – Kaptajn H.C. Lundgreens Legat[23]

Selected works

- Grønland, land og folk, 1927 (Travelbook) Freuchen's first book

- Storfanger, 1927 (Novel)

- Rømningsmand, 1928 (novel)

- Nordkaper, 1929 - The Sea Tyrant (novel)

- Ivalu, 1930 - Ivalu, the Eskimo Wife - suomennettu (novel)

- Knud Rasmussen. Mindeudgave. 3 vol, 1934 (Peter Freuchen, Therkel Mathiassen and Kaj Birket-Smith)

- Flugten til Sydamerika, 1935 (Memories)

- "Arctic Adventure: My Life in the Frozen North", Farrar & Rinehart, New York, Toronto, Copyright 1935.

- Min grønlandske ungdom, 1936 and 1953 (Memories)

- Nuoruuteni Grönlannissa (Memories)

- Min anden ungdom, 1938 (Memories)

- Sibiriske eventyr, 1939 (Memories)

- Diamantdronningen, 1941 (novel)

- Hvid mand, 1943 - White Man - Valkoinen mies eskimoiden parissa (novel)

- Eskimofortællinger, 1944 (novel)

- Solfjeld, 1944 (novel)

- Larions lov, 1948 - The Law of Larion (novel about the inland Indians along the Yukon river)

- Eskimodrengen Ivik, 1949 - Eskimopoika Ivik (novel)

- Nigger-Dan, 1951 (novel, aka The Legend of Daniel Williams)

- I al frimodighed 1953 (Memories)

- "Ice Floes and Flaming Water", 1954

- I all uppriktighet", 1954 (Memories)

- Vagrant Viking, 1954 (Memories)

- Fremdeles frimodig, 1955

- Fortfarende uppriktig"´, 1956 og 1960 (Memories)

- Fangsmænd i Melville-bugten, 1956 - Pyyntimiehiä Melville lahdella (novel)

- Fra Thule til Rio, 1957 (Memories)

- "Peter Freuchen's Book of the Seven Seas", Julian Messner, Inc., New York, Copyright 1957.

- Peter Freuchens bog om de syv have, 1959 (Documentary)

- "The Arctic Year", G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, Copyright 1958. (Peter Freuchen and Finn Salomonsen)

- "I Sailed with Rasmussen, 1958 (Documentary)

- Hvalfangerne, 1959 (novel)

- "Peter Freuchen's Adventures in the Arctic", Julian Messner, Inc., New York, Copyright 1960. (Edited by Dagmar Freuchen)

- Det arktiske år, 1961 - Arctic Year (Documentary)

- "Peter Freuchen's Book of the Eskimos", Peter Freuchen Estate. Cleveland Ohio, Copyright 1961.- (Edited by Dagmar Freuchen)

- Erindringer, 1963 - (Edited by Dagmar Freuchen)

References

- Niels Jensen. "Kaptajn H.C. Lundgreens Legat". Dansk litteraturpriser. Retrieved June 1, 2017.

External links

- 1886 births

- 1957 deaths

- Anti-fascists

- Danish amputees

- Danish polar explorers

- Danish anthropologists

- Danish emigrants to Greenland

- Danish emigrants to the United States

- Danish explorers

- Scandinavian explorers of North America

- Greenlandic polar explorers

- Danish journalists

- Danish resistance members

- Danish socialists

- Danish travel writers

- People from Guldborgsund Municipality

- University of Copenhagen alumni

- 20th-century anthropologists

- 20th-century journalists

Languages

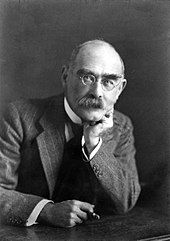

Rudyard Kipling

Rudyard Kipling | |

|---|---|

Kipling in 1895 | |

| Born | Joseph Rudyard Kipling 30 December 1865 Malabar Hill, Bombay Presidency, British India |

| Died | 18 January 1936 (aged 70) Fitzrovia, London, England |

| Resting place | Westminster Abbey |

| Occupation | Short-story writer, novelist, poet, journalist |

| Nationality | British |

| Genre | Short story, novel, children's literature, poetry, travel literature, science fiction |

| Notable works | The Jungle Book Just So Stories Kim Captains Courageous "If—" "Gunga Din" "The White Man's Burden" |

| Notable awards | Nobel Prize in Literature 1907 |

| Spouse | Caroline Starr Balestier

(m. 1892) |

| Children | |

| Signature | |

Joseph Rudyard Kipling (/ˈrʌdjərd/ RUD-yərd; 30 December 1865 – 18 January 1936)[1] was an English journalist, short-story writer, poet, and novelist. He was born in India, which inspired much of his work.

Kipling's works of fiction include The Jungle Book (1894), Kim (1901), and many short stories, including "The Man Who Would Be King" (1888).[2] His poems include "Mandalay" (1890), "Gunga Din" (1890), "The Gods of the Copybook Headings" (1919), "The White Man's Burden" (1899), and "If—" (1910). He is seen as an innovator in the art of the short story.[3] His children's books are classics; one critic noted "a versatile and luminous narrative gift." [4][5]

Kipling in the late 19th and early 20th centuries was among the United Kingdom's most popular writers.[3] Henry James said "Kipling strikes me personally as the most complete man of genius, as distinct from fine intelligence, that I have ever known."[3] In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature, as the first English-language writer to receive the prize, and at 41, its youngest recipient to date.[6] He was also sounded out for the British Poet Laureateship and several times for a knighthood, but declined both.[7] Following his death in 1936, his ashes were interred at Poets' Corner, part of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey.

Kipling's subsequent reputation has changed with the political and social climate of the age.[8][9] The contrasting views of him continued for much of the 20th century.[10][11] Literary critic Douglas Kerr wrote: "[Kipling] is still an author who can inspire passionate disagreement and his place in literary and cultural history is far from settled. But as the age of the European empires recedes, he is recognised as an incomparable, if controversial, interpreter of how empire was experienced. That, and an increasing recognition of his extraordinary narrative gifts, make him a force to be reckoned with."[12]

Childhood (1865–1882)

Rudyard Kipling was born on 30 December 1865 in Bombay, in the Bombay Presidency of British India, to Alice Kipling (née MacDonald) and John Lockwood Kipling.[13] Alice (one of the four noted MacDonald sisters)[14] was a vivacious woman,[15] of whom Lord Dufferin would say, "Dullness and Mrs Kipling cannot exist in the same room."[3][16][17] John Lockwood Kipling, a sculptor and pottery designer, was the Principal and Professor of Architectural Sculpture at the newly founded Sir Jamsetjee Jeejebhoy School of Art in Bombay.[15]

John Lockwood and Alice had met in 1863 and courted at Rudyard Lake in Rudyard, Staffordshire, England. They married and moved to India in 1865. They had been so moved by the beauty of the Rudyard Lake area that they named their first child after it. Two of Alice's sisters were married to artists: Georgiana to the painter Edward Burne-Jones, and her sister Agnes to Edward Poynter. Kipling's most prominent relative was his first cousin, Stanley Baldwin, who was Conservative Prime Minister three times in the 1920s and 1930s.[18]

Kipling's birth home on the campus of the J.J. School of Art in Bombay was for many years used as the Dean's residence.[19] Although a cottage bears a plaque noting it as his birth site, the original one may have been torn down and replaced decades ago.[20] Some historians and conservationists take the view that the bungalow marks a site merely close to the home of Kipling's birth, as it was built in 1882 – about 15 years after Kipling was born. Kipling seems to have said as much to the Dean when visiting J. J. School in the 1930s.[21]

Kipling wrote of Bombay:

Mother of Cities to me,

For I was born in her gate,

Between the palms and the sea,

Where the world-end steamers wait.[22]

According to Bernice M. Murphy, "Kipling's parents considered themselves 'Anglo-Indians' [a term used in the 19th century for people of British origin living in India] and so too would their son, though he spent the bulk of his life elsewhere. Complex issues of identity and national allegiance would become prominent in his fiction."[23]

Kipling referred to such conflicts. For example: "In the afternoon heats before we took our sleep, she (the Portuguese ayah, or nanny) or Meeta (the Hindu bearer, or male attendant) would tell us stories and Indian nursery songs all unforgotten, and we were sent into the dining-room after we had been dressed, with the caution 'Speak English now to Papa and Mamma.' So one spoke 'English', haltingly translated out of the vernacular idiom that one thought and dreamed in."[24]

Education in Britain

Kipling's days of "strong light and darkness" in Bombay ended when he was five.[24] As was the custom in British India, he and his three-year-old sister Alice ("Trix") were taken to the United Kingdom – in their case to Southsea, Portsmouth – to live with a couple who boarded children of British nationals living abroad.[25] For the next six years (from October 1871 to April 1877), the children lived with the couple – Captain Pryse Agar Holloway, once an officer in the merchant navy, and Sarah Holloway – at their house, Lorne Lodge, 4 Campbell Road, Southsea.[26]

In his autobiography published 65 years later, Kipling recalled the stay with horror, and wondered if the combination of cruelty and neglect which he experienced there at the hands of Mrs Holloway might not have hastened the onset of his literary life: "If you cross-examine a child of seven or eight on his day's doings (specially when he wants to go to sleep) he will contradict himself very satisfactorily. If each contradiction be set down as a lie and retailed at breakfast, life is not easy. I have known a certain amount of bullying, but this was calculated torture – religious as well as scientific. Yet it made me give attention to the lies I soon found it necessary to tell: and this, I presume, is the foundation of literary effort." [24]

Trix fared better at Lorne Lodge; Mrs Holloway apparently hoped that Trix would eventually marry the Holloways' son.[27] The two Kipling children, however, had no relatives in England they could visit, except that they spent a month each Christmas with a maternal aunt Georgiana ("Georgy") and her husband, Edward Burne-Jones, at their house, The Grange, in Fulham, London, which Kipling called "a paradise which I verily believe saved me."[24]

In the spring of 1877, Alice returned from India and removed the children from Lorne Lodge. Kipling remembers "Often and often afterwards, the beloved Aunt would ask me why I had never told any one how I was being treated. Children tell little more than animals, for what comes to them they accept as eternally established. Also, badly-treated children have a clear notion of what they are likely to get if they betray the secrets of a prison-house before they are clear of it."[24]

Alice took the children during Spring 1877 to Goldings Farm at Loughton, where a carefree summer and autumn was spent on the farm and adjoining Forest, some of the time with Stanley Baldwin. In January 1878, Kipling was admitted to the United Services College at Westward Ho!, Devon, a school recently founded to prepare boys for the army. It proved rough going for him at first, but later led to firm friendships and provided the setting for his schoolboy stories Stalky & Co. (1899).[27] While there, Kipling met and fell in love with Florence Garrard, who was boarding with Trix at Southsea (to which Trix had returned). Florence became the model for Maisie in Kipling's first novel, The Light That Failed (1891).[27]

Return to India

Near the end of his schooling, it was decided that Kipling did not have the academic ability to get into Oxford University on a scholarship.[27] His parents lacked the wherewithal to finance him,[15] and so Kipling's father obtained a job for him in Lahore, where the father served as Principal of the Mayo College of Art and Curator of the Lahore Museum. Kipling was to be assistant editor of a local newspaper, the Civil and Military Gazette.

He sailed for India on 20 September 1882 and arrived in Bombay on 18 October. He described the moment years later: "So, at sixteen years and nine months, but looking four or five years older, and adorned with real whiskers which the scandalised Mother abolished within one hour of beholding, I found myself at Bombay where I was born, moving among sights and smells that made me deliver in the vernacular sentences whose meaning I knew not. Other Indian-born boys have told me how the same thing happened to them."[24] This arrival changed Kipling, as he explains: "There were yet three or four days' rail to Lahore, where my people lived. After these, my English years fell away, nor ever, I think, came back in full strength." [24]

Early adult life (1882–1914)

From 1883 to 1889, Kipling worked in British India for local newspapers such as the Civil and Military Gazette in Lahore and The Pioneer in Allahabad.[24]

The former, which was the newspaper Kipling was to call his "mistress and most true love," [24] appeared six days a week throughout the year, except for one-day breaks for Christmas and Easter. Stephen Wheeler, the editor, worked Kipling hard, but Kipling's need to write was unstoppable. In 1886, he published his first collection of verse, Departmental Ditties. That year also brought a change of editors at the newspaper; Kay Robinson, the new editor, allowed more creative freedom and Kipling was asked to contribute short stories to the newspaper.[4]

In an article printed in the Chums boys' annual, an ex-colleague of Kipling's stated that "he never knew such a fellow for ink – he simply revelled in it, filling up his pen viciously, and then throwing the contents all over the office, so that it was almost dangerous to approach him."[28] The anecdote continues: "In the hot weather when he (Kipling) wore only white trousers and a thin vest, he is said to have resembled a Dalmatian dog more than a human being, for he was spotted all over with ink in every direction."

In the summer of 1883, Kipling visited Shimla, then Simla, a well-known hill station and the summer capital of British India. By then it was the practice for the Viceroy of India and government to move to Simla for six months, and the town became a "centre of power as well as pleasure." [4] Kipling's family became annual visitors to Simla, and Lockwood Kipling was asked to serve in Christ Church there. Rudyard Kipling returned to Simla for his annual leave each year from 1885 to 1888, and the town featured prominently in many stories he wrote for the Gazette.[4] "My month's leave at Simla, or whatever Hill Station my people went to, was pure joy – every golden hour counted. It began in heat and discomfort, by rail and road. It ended in the cool evening, with a wood fire in one's bedroom, and next morn – thirty more of them ahead! – the early cup of tea, the Mother who brought it in, and the long talks of us all together again. One had leisure to work, too, at whatever play-work was in one's head, and that was usually full."[24]

Back in Lahore, 39 of his stories appeared in the Gazette between November 1886 and June 1887. Kipling included most of them in Plain Tales from the Hills, his first prose collection, published in Calcutta in January 1888, a month after his 22nd birthday. Kipling's time in Lahore, however, had come to an end. In November 1887, he was moved to the Gazette's larger sister newspaper, The Pioneer, in Allahabad in the United Provinces, where he worked as assistant editor and lived in Belvedere House from 1888 to 1889.[29][30]

Kipling's writing continued at a frenetic pace. In 1888, he published six collections of short stories: Soldiers Three, The Story of the Gadsbys, In Black and White, Under the Deodars, The Phantom Rickshaw, and Wee Willie Winkie. These contain a total of 41 stories, some quite long. In addition, as The Pioneer's special correspondent in the western region of Rajputana, he wrote many sketches that were later collected in Letters of Marque and published in From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel.[4]

Kipling was discharged from The Pioneer in early 1889 after a dispute. By this time, he had been increasingly thinking of his future. He sold the rights to his six volumes of stories for £200 and a small royalty, and the Plain Tales for £50; in addition, he received six-months' salary from The Pioneer, in lieu of notice.[24]

Return to London

Kipling decided to use the money to move to London, as the literary centre of the British Empire. On 9 March 1889, he left India, travelling first to San Francisco via Rangoon, Singapore, Hong Kong and Japan. Kipling was favourably impressed by Japan, calling its people "gracious folk and fair manners." [31]

Kipling later wrote that he "had lost his heart" to a geisha whom he called O-Toyo, writing while in the United States during the same trip across the Pacific, "I had left the innocent East far behind.... Weeping softly for O-Toyo.... O-Toyo was a darling."[31] Kipling then travelled through the United States, writing articles for The Pioneer that were later published in From Sea to Sea and Other Sketches, Letters of Travel.[32]

Starting his North American travels in San Francisco, Kipling went north to Portland, Oregon, then Seattle, Washington, up to Victoria and Vancouver, British Columbia, through Medicine Hat, Alberta, back into the US to Yellowstone National Park, down to Salt Lake City, then east to Omaha, Nebraska and on to Chicago, Illinois, then to Beaver, Pennsylvania on the Ohio River to visit the Hill family. From there, he went to Chautauqua with Professor Hill, and later to Niagara Falls, Toronto, Washington, D.C., New York, and Boston.[32]

In the course of this journey he met Mark Twain in Elmira, New York, and was deeply impressed. Kipling arrived unannounced at Twain's home, and later wrote that as he rang the doorbell, "It occurred to me for the first time that Mark Twain might possibly have other engagements other than the entertainment of escaped lunatics from India, be they ever so full of admiration."[33]

As it was, Twain gladly welcomed Kipling and had a two-hour conversation with him on trends in Anglo-American literature and about what Twain was going to write in a sequel to Tom Sawyer, with Twain assuring Kipling that a sequel was coming, although he had not decided upon the ending: either Sawyer would be elected to Congress or he would be hanged.[33] Twain also passed along the literary advice that an author should "get your facts first and then you can distort 'em as much as you please."[33] Twain, who rather liked Kipling, later wrote of their meeting: "Between us, we cover all knowledge; he covers all that can be known and I cover the rest."[33] Kipling then crossed the Atlantic to Liverpool in October 1889. He soon made his début in the London literary world, to great acclaim.[3]

London

In London, Kipling had several stories accepted by magazines. He found a place to live for the next two years at Villiers Street, near Charing Cross (in a building subsequently named Kipling House):

Meantime, I had found me quarters in Villiers Street, Strand, which forty-six years ago was primitive and passionate in its habits and population. My rooms were small, not over-clean or well-kept, but from my desk I could look out of my window through the fanlight of Gatti's Music-Hall entrance, across the street, almost on to its stage. The Charing Cross trains rumbled through my dreams on one side, the boom of the Strand on the other, while, before my windows, Father Thames under the Shot tower walked up and down with his traffic.[34]

In the next two years, he published a novel, The Light That Failed, had a nervous breakdown, and met an American writer and publishing agent, Wolcott Balestier, with whom he collaborated on a novel, The Naulahka (a title which he uncharacteristically misspelt; see below).[15] In 1891, as advised by his doctors, Kipling took another sea voyage, to South Africa, Australia, New Zealand, and once again India.[15] He cut short his plans to spend Christmas with his family in India when he heard of Balestier's sudden death from typhoid fever and decided to return to London immediately. Before his return, he had used the telegram to propose to, and be accepted by, Wolcott's sister, Caroline Starr Balestier (1862–1939), called "Carrie", whom he had met a year earlier, and with whom he had apparently been having an intermittent romance.[15] Meanwhile, late in 1891, a collection of his short stories on the British in India, Life's Handicap, was published in London.[35]

On 18 January 1892, Carrie Balestier (aged 29) and Rudyard Kipling (aged 26) married in London, in the "thick of an influenza epidemic, when the undertakers had run out of black horses and the dead had to be content with brown ones."[24] The wedding was held at All Souls Church, Langham Place. Henry James gave away the bride.

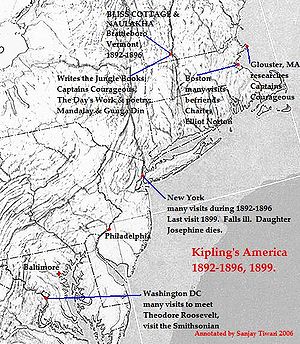

United States

Kipling and his wife settled upon a honeymoon that took them first to the United States (including a stop at the Balestier family estate near Brattleboro, Vermont) and then to Japan.[15] On arriving in Yokohama, they discovered that their bank, The New Oriental Banking Corporation, had failed. Taking this loss in their stride, they returned to the U.S., back to Vermont – Carrie by this time was pregnant with their first child – and rented a small cottage on a farm near Brattleboro for $10 a month.[24] According to Kipling, "We furnished it with a simplicity that fore-ran the hire-purchase system. We bought, second or third hand, a huge, hot-air stove which we installed in the cellar. We cut generous holes in our thin floors for its eight-inch [20 cm] tin pipes (why we were not burned in our beds each week of the winter I never can understand) and we were extraordinarily and self-centredly content."[24]

In this house, which they called Bliss Cottage, their first child, Josephine, was born "in three-foot of snow on the night of 29th December, 1892. Her Mother's birthday being the 31st and mine the 30th of the same month, we congratulated her on her sense of the fitness of things...."[24]

It was also in this cottage that the first dawnings of The Jungle Books came to Kipling: "The workroom in the Bliss Cottage was seven feet by eight, and from December to April, the snow lay level with its window-sill. It chanced that I had written a tale about Indian Forestry work which included a boy who had been brought up by wolves. In the stillness, and suspense, of the winter of '92 some memory of the Masonic Lions of my childhood's magazine, and a phrase in Haggard's Nada the Lily, combined with the echo of this tale. After blocking out the main idea in my head, the pen took charge, and I watched it begin to write stories about Mowgli and animals, which later grew into the two Jungle Books."[24]

With Josephine's arrival, Bliss Cottage was felt to be congested, so eventually the couple bought land – 10 acres (4.0 ha) on a rocky hillside overlooking the Connecticut River – from Carrie's brother Beatty Balestier and built their own house. Kipling named this Naulakha, in honour of Wolcott and of their collaboration, and this time the name was spelt correctly.[15] From his early years in Lahore (1882–87), Kipling had become enamoured with the Mughal architecture,[36] especially the Naulakha pavilion situated in Lahore Fort, which eventually inspired the title of his novel as well as the house.[37] The house still stands on Kipling Road, three miles (5 km) north of Brattleboro in Dummerston, Vermont: a big, secluded, dark-green house, with shingled roof and sides, which Kipling called his "ship," and which brought him "sunshine and a mind at ease." [15] His seclusion in Vermont, combined with his healthy "sane clean life," made Kipling both inventive and prolific.

In a mere four years he produced, along with the Jungle Books, a book of short stories (The Day's Work), a novel (Captains Courageous), and a profusion of poetry, including the volume The Seven Seas. The collection of Barrack-Room Ballads was issued in March 1892, first published individually for the most part in 1890, and contained his poems "Mandalay" and "Gunga Din." He especially enjoyed writing the Jungle Books and also corresponding with many children who wrote to him about them.[15]

Life in New England

The writing life in Naulakha was occasionally interrupted by visitors, including his father, who visited soon after his retirement in 1893,[15] and the British writer Arthur Conan Doyle, who brought his golf clubs, stayed for two days, and gave Kipling an extended golf lesson.[38][39] Kipling seemed to take to golf, occasionally practising with the local Congregational minister and even playing with red-painted balls when the ground was covered in snow.[13][39] However, winter golf was "not altogether a success because there were no limits to a drive; the ball might skid two miles (3 km) down the long slope to Connecticut river."[13]

Kipling loved the outdoors,[15] not least of whose marvels in Vermont was the turning of the leaves each fall. He described this moment in a letter: "A little maple began it, flaming blood-red of a sudden where he stood against the dark green of a pine-belt. Next morning there was an answering signal from the swamp where the sumacs grow. Three days later, the hill-sides as fast as the eye could range were afire, and the roads paved, with crimson and gold. Then a wet wind blew, and ruined all the uniforms of that gorgeous army; and the oaks, who had held themselves in reserve, buckled on their dull and bronzed cuirasses and stood it out stiffly to the last blown leaf, till nothing remained but pencil-shadings of bare boughs, and one could see into the most private heart of the woods."[40]

In February 1896, Elsie Kipling was born, the couple's second daughter. By this time, according to several biographers, their marital relationship was no longer light-hearted and spontaneous.[41] Although they would always remain loyal to each other, they seemed now to have fallen into set roles.[15] In a letter to a friend who had become engaged around this time, the 30‑year‑old Kipling offered this sombre counsel: marriage principally taught "the tougher virtues – such as humility, restraint, order, and forethought."[42] Later in the same year, he temporarily taught at Bishop's College School in Quebec, Canada.[43]

The Kiplings loved life in Vermont and might have lived out their lives there, were it not for two incidents – one of global politics, the other of family discord. By the early 1890s, the United Kingdom and Venezuela were in a border dispute involving British Guiana. The U.S. had made several offers to arbitrate, but in 1895, the new American Secretary of State Richard Olney upped the ante by arguing for the American "right" to arbitrate on grounds of sovereignty on the continent (see the Olney interpretation as an extension of the Monroe Doctrine).[15] This raised hackles in Britain, and the situation grew into a major Anglo-American crisis, with talk of war on both sides.

Although the crisis eased into greater United States–British cooperation, Kipling was bewildered by what he felt was persistent anti-British sentiment in the U.S., especially in the press.[15] He wrote in a letter that it felt like being "aimed at with a decanter across a friendly dinner table."[42] By January 1896, he had decided[13] to end his family's "good wholesome life" in the U.S. and seek their fortunes elsewhere.

A family dispute became the final straw. For some time, relations between Carrie and her brother Beatty Balestier had been strained, owing to his drinking and insolvency. In May 1896, an inebriated Beatty encountered Kipling on the street and threatened him with physical harm.[15] The incident led to Beatty's eventual arrest, but in the subsequent hearing and the resulting publicity, Kipling's privacy was destroyed, and he was left feeling miserable and exhausted. In July 1896, a week before the hearing was to resume, the Kiplings packed their belongings, left the United States and returned to England.[13]

Devon

By September 1896, the Kiplings were in Torquay, Devon, on the south-western coast of England, in a hillside home overlooking the English Channel. Although Kipling did not much care for his new house, whose design, he claimed, left its occupants feeling dispirited and gloomy, he managed to remain productive and socially active.[15]

Kipling was now a famous man, and in the previous two or three years had increasingly been making political pronouncements in his writings. The Kiplings had welcomed their first son, John, in August 1897. Kipling had begun work on two poems, "Recessional" (1897) and "The White Man's Burden" (1899), which were to create controversy when published. Regarded by some as anthems for enlightened and duty-bound empire-building (capturing the mood of the Victorian era), the poems were seen by others as propaganda for brazen-faced imperialism and its attendant racial attitudes; still others saw irony in the poems and warnings of the perils of empire.[15]

Take up the White Man's burden—

Send forth the best ye breed—

Go, bind your sons to exile

To serve your captives' need;

To wait, in heavy harness,

On fluttered folk and wild—

Your new-caught sullen peoples,

Half devil and half child.

—The White Man's Burden[44]

There was also foreboding in the poems, a sense that all could yet come to naught.[45]

A prolific writer during his time in Torquay, he also wrote Stalky & Co., a collection of school stories (born of his experience at the United Services College in Westward Ho!), whose juvenile protagonists display a know-it-all, cynical outlook on patriotism and authority. According to his family, Kipling enjoyed reading aloud stories from Stalky & Co. to them and often went into spasms of laughter over his own jokes.[15]

Visits to South Africa

In early 1898, the Kiplings travelled to South Africa for their winter holiday, so beginning an annual tradition which (except the following year) would last until 1908. They would stay in "The Woolsack," a house on Cecil Rhodes's estate at Groote Schuur (now a student residence for the University of Cape Town), within walking distance of Rhodes' mansion.[47]

With his new reputation as Poet of the Empire, Kipling was warmly received by some of the influential politicians of the Cape Colony, including Rhodes, Sir Alfred Milner, and Leander Starr Jameson. Kipling cultivated their friendship and came to admire the men and their politics. The period 1898–1910 was crucial in the history of South Africa and included the Second Boer War (1899–1902), the ensuing peace treaty, and the 1910 formation of the Union of South Africa. Back in England, Kipling wrote poetry in support of the British cause in the Boer War and on his next visit to South Africa in early 1900, became a correspondent for The Friend newspaper in Bloemfontein, which had been commandeered by Lord Roberts for British troops.[48]

Although his journalistic stint was to last only two weeks, it was Kipling's first work on a newspaper staff since he left The Pioneer in Allahabad more than ten years before.[15] At The Friend, he made lifelong friendships with Perceval Landon, H. A. Gwynne, and others.[49] He also wrote articles published more widely expressing his views on the conflict.[50] Kipling penned an inscription for the Honoured Dead Memorial (Siege memorial) in Kimberley.

Sussex

In 1897, Kipling moved from Torquay to Rottingdean, near Brighton, East Sussex – first to North End House and then to the Elms.[51] In 1902, Kipling bought Bateman's, a house built in 1634 and located in rural Burwash.

Bateman's was Kipling's home from 1902 until his death in 1936.[52] The house and its surrounding buildings, the mill and 33 acres (13 ha), were bought for £9,300. It had no bathroom, no running water upstairs and no electricity, but Kipling loved it: "Behold us, lawful owners of a grey stone lichened house – A.D. 1634 over the door – beamed, panelled, with old oak staircase, and all untouched and unfaked. It is a good and peaceable place. We have loved it ever since our first sight of it" (from a November 1902 letter).[53][54]

In the non-fiction realm, he became involved in the debate over the British response to the rise in German naval power known as the Tirpitz Plan, to build a fleet to challenge the Royal Navy, publishing a series of articles in 1898 collected as A Fleet in Being. On a visit to the United States in 1899, Kipling and his daughter Josephine developed pneumonia, from which she eventually died.

-Kim

In the wake of his daughter's death, Kipling concentrated on collecting material for what became Just So Stories for Little Children, published in 1902, the year after Kim.[55] The American literary scholar David Scott has argued that Kim disproves the claim by Edward Said about Kipling as a promoter of Orientalism as Kipling – who was deeply interested in Buddhism – as he presented Tibetan Buddhism in a fairly sympathetic light and aspects of the novel appeared to reflect a Buddhist understanding of the universe.[56][57] Kipling was offended by the German Emperor Wilhelm II's Hun speech (Hunnenrede) in 1900, urging German troops being sent to China to crush the Boxer Rebellion to behave like "Huns" and take no prisoners.[58]

In a 1902 poem, The Rowers, Kipling attacked the Kaiser as a threat to Britain and made the first use of the term "Hun" as an anti-German insult, using Wilhelm's own words and the actions of German troops in China to portray Germans as essentially barbarian.[58] In an interview with the French newspaper Le Figaro, the Francophile Kipling called Germany a menace and called for an Anglo-French alliance to stop it.[58] In another letter at the same time, Kipling described the "unfrei peoples of Central Europe" as living in "the Middle Ages with machine guns." [58]

Speculative fiction

Kipling wrote a number of speculative fiction short stories, including "The Army of a Dream," in which he sought to show a more efficient and responsible army than the hereditary bureaucracy of England at the time, and two science fiction stories: "With the Night Mail" (1905) and "As Easy As A.B.C." (1912). Both were set in the 21st century in Kipling's Aerial Board of Control universe. They read like modern hard science fiction,[59] and introduced the literary technique known as indirect exposition, which would later become one of science fiction writer Robert Heinlein's hallmarks. This technique is one that Kipling picked up in India, and used to solve the problem of his English readers not understanding much about Indian society, when writing The Jungle Book.[60]

Nobel laureate and beyond

In 1907, he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature, having been nominated in that year by Charles Oman, professor at the University of Oxford.[61] The prize citation said it was "in consideration of the power of observation, originality of imagination, virility of ideas and remarkable talent for narration which characterize the creations of this world-famous author." Nobel prizes had been established in 1901 and Kipling was the first English-language recipient. At the award ceremony in Stockholm on 10 December 1907, the Permanent Secretary of the Swedish Academy, Carl David af Wirsén, praised both Kipling and three centuries of English literature:

The Swedish Academy, in awarding the Nobel Prize in Literature this year to Rudyard Kipling, desires to pay a tribute of homage to the literature of England, so rich in manifold glories, and to the greatest genius in the realm of narrative that that country has produced in our times.[62]

To "book-end" this achievement came the publication of two connected poetry and story collections: Puck of Pook's Hill (1906), and Rewards and Fairies (1910). The latter contained the poem "If—." In a 1995 BBC opinion poll, it was voted the UK's favourite poem.[63] This exhortation to self-control and stoicism is arguably Kipling's most famous poem.[63]

Such was Kipling's popularity that he was asked by his friend Max Aitken to intervene in the 1911 Canadian election on behalf of the Conservatives.[64] In 1911, the major issue in Canada was a reciprocity treaty with the United States signed by the Liberal Prime Minister Sir Wilfrid Laurier and vigorously opposed by the Conservatives under Sir Robert Borden. On 7 September 1911, the Montreal Daily Star newspaper published a front-page appeal against the agreement by Kipling, who wrote: "It is her own soul that Canada risks today. Once that soul is pawned for any consideration, Canada must inevitably conform to the commercial, legal, financial, social, and ethical standards which will be imposed on her by the sheer admitted weight of the United States."[64] At the time, the Montreal Daily Star was Canada's most read newspaper. Over the next week, Kipling's appeal was reprinted in every English newspaper in Canada and is credited with helping to turn Canadian public opinion against the Liberal government.[64]

Kipling sympathised with the anti-Home Rule stance of Irish Unionists, who opposed Irish autonomy. He was friends with Edward Carson, the Dublin-born leader of Ulster Unionism, who raised the Ulster Volunteers to prevent Home Rule in Ireland. Kipling wrote in a letter to a friend that Ireland was not a nation, and that before the English arrived in 1169, the Irish were a gang of cattle thieves living in savagery and killing each other while "writing dreary poems" about it all. In his view it was only British rule that allowed Ireland to advance.[65] A visit to Ireland in 1911 confirmed Kipling's prejudices. He wrote that the Irish countryside was beautiful, but spoiled by what he called the ugly homes of Irish farmers, with Kipling adding that God had made the Irish into poets having "deprived them of love of line or knowledge of colour." [66] In contrast, Kipling had nothing but praise for the "decent folk" of the Protestant minority and Unionist Ulster, free from the threat of "constant mob violence".[66]

Kipling wrote the poem "Ulster" in 1912, reflecting his Unionist politics. Kipling often referred to the Irish Unionists as "our party." [67] Kipling had no sympathy or understanding for Irish nationalism, seeing Home Rule as an act of treason by the government of the Liberal Prime Minister H. H. Asquith that would plunge Ireland into the Dark Ages and allow the Irish Catholic majority to oppress the Protestant minority.[68] The scholar David Gilmour wrote that Kipling's lack of understanding of Ireland could be seen in his attack on John Redmond – the Anglophile leader of the Irish Parliamentary Party who wanted Home Rule because he believed it was the best way of keeping the United Kingdom together – as a traitor working to break up the United Kingdom.[69] Ulster was first publicly read at an Unionist rally in Belfast, where the largest Union Jack ever made was unfolded.[69] Kipling admitted it was meant to strike a "hard blow" against the Asquith government's Home Rule bill: "Rebellion, rapine, hate, Oppression, wrong and greed, Are loosed to rule our fate, By England's act and deed." [66] Ulster generated much controversy with the Conservative MP Sir Mark Sykes – who as a Unionist was opposed to the Home Rule bill – condemning Ulster in The Morning Post as a "direct appeal to ignorance and a deliberate attempt to foster religious hate." [69]

Kipling was a staunch opponent of Bolshevism, a position which he shared with his friend Henry Rider Haggard. The two had bonded on Kipling's arrival in London in 1889 largely due to their shared opinions, and remained lifelong friends.

Freemasonry

According to the English magazine Masonic Illustrated, Kipling became a Freemason in about 1885, before the usual minimum age of 21,[70] being initiated into Hope and Perseverance Lodge No. 782 in Lahore. He later wrote to The Times, "I was Secretary for some years of the Lodge... which included Brethren of at least four creeds. I was entered [as an Apprentice] by a member from Brahmo Somaj, a Hindu, passed [to the degree of Fellow Craft] by a Mohammedan, and raised [to the degree of Master Mason] by an Englishman. Our Tyler was an Indian Jew." Kipling received not only the three degrees of Craft Masonry but also the side degrees of Mark Master Mason and Royal Ark Mariner.[71]

Kipling so loved his Masonic experience that he memorialised its ideals in his poem "The Mother Lodge," [70] and used the fraternity and its symbols as vital plot devices in his novella The Man Who Would Be King.[72]

First World War (1914–1918)

At the beginning of the First World War, like many other writers, Kipling wrote pamphlets and poems enthusiastically supporting the UK war aims of restoring Belgium, after it had been occupied by Germany, together with generalised statements that Britain was standing up for the cause of good. In September 1914, Kipling was asked by the government to write propaganda, an offer that he accepted.[73] Kipling's pamphlets and stories were popular with the British people during the war, his major themes being to glorify the British military as the place for heroic men to be, while citing German atrocities against Belgian civilians and the stories of women brutalised by a horrific war unleashed by Germany, yet surviving and triumphing in spite of their suffering.[73]

Kipling was enraged by reports of the Rape of Belgium together with the sinking of the RMS Lusitania in 1915, which he saw as a deeply inhumane act, which led him to see the war as a crusade for civilisation against barbarism.[74] In a 1915 speech, Kipling declared, "There was no crime, no cruelty, no abomination that the mind of men can conceive of which the German has not perpetrated, is not perpetrating, and will not perpetrate if he is allowed to go on.... Today, there are only two divisions in the world... human beings and Germans."[74]

Alongside his passionate antipathy towards Germany, Kipling was privately deeply critical of how the war was being fought by the British Army, complaining as early as October 1914 that Germany should have been defeated by now, and something must be wrong with the British Army.[75] Kipling, who was shocked by the heavy losses that the British Expeditionary Force had taken by the autumn of 1914, blamed the entire pre-war generation of British politicians who, he argued, had failed to learn the lessons of the Boer War. Thus thousands of British soldiers were now paying with their lives for their failure in the fields of France and Belgium.[75]

Kipling had scorn for men who shirked duty in the First World War. In "The New Army in Training"[76] (1915), Kipling concluded by saying:

This much we can realise, even though we are so close to it, the old safe instinct saves us from triumph and exultation. But what will be the position in years to come of the young man who has deliberately elected to outcaste himself from this all-embracing brotherhood? What of his family, and, above all, what of his descendants, when the books have been closed and the last balance struck of sacrifice and sorrow in every hamlet, village, parish, suburb, city, shire, district, province, and Dominion throughout the Empire?

In 1914, Kipling was one of 53 leading British authors — a number that included H. G. Wells, Arthur Conan Doyle and Thomas Hardy — who signed their names to the “Authors’ Declaration.” This manifesto declared that the German invasion of Belgium had been a brutal crime, and that Britain “could not without dishonour have refused to take part in the present war.”[77]

Death of John Kipling

Kipling's son John was killed in action at the Battle of Loos in September 1915, at age 18. John initially wanted to join the Royal Navy, but having had his application turned down after a failed medical examination due to poor eyesight, he opted to apply for military service as an army officer. Again, his eyesight was an issue during the medical examination. In fact, he tried twice to enlist, but was rejected. His father had been lifelong friends with Lord Roberts, former commander-in-chief of the British Army, and colonel of the Irish Guards, and at Rudyard's request, John was accepted into the Irish Guards.[73]

John Kipling was sent to Loos two days into the battle in a reinforcement contingent. He was last seen stumbling through the mud blindly, with a possible facial injury. A body identified as his was found in 1992, although that identification has been challenged.[78][79][80] In 2015, the Commonwealth War Grave Commission confirmed that it had correctly identified the burial place of John Kipling;[81] they record his date of death as 27 September 1915, and that he is buried at St Mary's A.D.S. Cemetery, Haisnes.[82]

After his son's death, in a poem titled "Epitaphs of the War," Kipling wrote "If any question why we died / Tell them, because our fathers lied." Critics have speculated that these words may express Kipling's guilt over his role in arranging John's commission.[83] Professor Tracy Bilsing contends that the line refers to Kipling's disgust that British leaders failed to learn the lessons of the Boer War, and were unprepared for the struggle with Germany in 1914, with the "lie" of the "fathers" being that the British Army was prepared for any war when it was not.[73]

John's death has been linked to Kipling's 1916 poem "My Boy Jack," notably in the play My Boy Jack and its subsequent television adaptation, along with the documentary Rudyard Kipling: A Remembrance Tale. However, the poem was originally published at the head of a story about the Battle of Jutland and appears to refer to a death at sea; the "Jack" referred to is probably a generic "Jack Tar." [84] In the Kipling family, Jack was the name of the family dog, while John Kipling was always John, making the identification of the protagonist of "My Boy Jack" with John Kipling somewhat questionable. However, Kipling was indeed emotionally devastated by the death of his son. He is said to have assuaged his grief by reading the novels of Jane Austen aloud to his wife and daughter.[85] During the war, he wrote a booklet The Fringes of the Fleet[86] containing essays and poems on various nautical subjects of the war. Some of these were set to music by the English composer Edward Elgar.

Kipling became friends with a French soldier named Maurice Hammoneau, whose life had been saved in the First World War when his copy of Kim, which he had in his left breast pocket, stopped a bullet. Hammoneau presented Kipling with the book, with bullet still embedded, and his Croix de Guerre as a token of gratitude. They continued to correspond, and when Hammoneau had a son, Kipling insisted on returning the book and medal.[87]

On 1 August 1918, the poem "The Old Volunteer" appeared under his name in The Times. The next day, he wrote to the newspaper to disclaim authorship and a correction appeared. Although The Times employed a private detective to investigate, the detective appears to have suspected Kipling himself of being the author, and the identity of the hoaxer was never established.[88]

After the war (1918–1936)

Partly in response to John's death, Kipling joined Sir Fabian Ware's Imperial War Graves Commission (now the Commonwealth War Graves Commission), the group responsible for the garden-like British war graves that can be found to this day dotted along the former Western Front and the other places in the world where British Empire troops lie buried. His main contributions to the project were his selection of the biblical phrase, "Their Name Liveth For Evermore" (Ecclesiasticus 44.14, KJV), found on the Stones of Remembrance in larger war cemeteries, and his suggestion of the phrase "Known unto God" for the gravestones of unidentified servicemen. He also chose the inscription "The Glorious Dead" on the Cenotaph, Whitehall, London. Additionally, he wrote a two-volume history of the Irish Guards, his son's regiment, published in 1923 and seen as one of the finest examples of regimental history.[89]

Kipling's short story "The Gardener" depicts visits to the war cemeteries, and the poem "The King's Pilgrimage" (1922) a journey which King George V made, touring the cemeteries and memorials under construction by the Imperial War Graves Commission. With the increasing popularity of the automobile, Kipling became a motoring correspondent for the British press, writing enthusiastically of trips around England and abroad, though he was usually driven by a chauffeur.

After the war, Kipling was sceptical of the Fourteen Points and the League of Nations, but had hopes that the United States would abandon isolationism and the post-war world be dominated by an Anglo-French-American alliance.[90] He hoped the United States would take on a League of Nations mandate for Armenia as the best way of preventing isolationism, and hoped that Theodore Roosevelt, whom Kipling admired, would again become president.[90] Kipling was saddened by Roosevelt's death in 1919, believing him to be the only American politician capable of keeping the United States in the "game" of world politics.[91]

Kipling was hostile towards communism, writing of the Bolshevik take-over in 1917 that one sixth of the world had "passed bodily out of civilization."[92] In a 1918 poem, Kipling wrote of Soviet Russia that everything good in Russia had been destroyed by the Bolsheviks – all that was left was "the sound of weeping and the sight of burning fire, and the shadow of a people trampled into the mire." [92]

In 1920, Kipling co-founded the Liberty League[93] with Haggard and Lord Sydenham. This short-lived enterprise focused on promoting classic liberal ideals as a response to the rising power of communist tendencies within Great Britain, or as Kipling put it, "to combat the advance of Bolshevism." [94][95]

In 1922, Kipling, having referred to the work of engineers in some of his poems, such as "The Sons of Martha," "Sappers," and "McAndrew's Hymn," [96] and in other writings, including short-story anthologies such as The Day's Work,[97] was asked by a University of Toronto civil engineering professor, Herbert E. T. Haultain, for assistance in developing a dignified obligation and ceremony for graduating engineering students. Kipling was enthusiastic in his response and shortly produced both, formally titled "The Ritual of the Calling of an Engineer." Today engineering graduates all across Canada are presented with an iron ring at a ceremony to remind them of their obligation to society.[98][99] In 1922 Kipling became Lord Rector of St Andrews University in Scotland, a three-year position.

Kipling, as a Francophile, argued strongly for an Anglo-French alliance to uphold the peace, calling Britain and France in 1920 the "twin fortresses of European civilization." [100] Similarly, Kipling repeatedly warned against revising the Treaty of Versailles in Germany's favour, which he predicted would lead to a new world war.[100] An admirer of Raymond Poincaré, Kipling was one of few British intellectuals who supported the French Occupation of the Ruhr in 1923, at a time when the British government and most public opinion was against the French position.[101] In contrast to the popular British view of Poincaré as a cruel bully intent on impoverishing Germany with unreasonable reparations, Kipling argued that he was rightfully trying to preserve France as a great power in the face of an unfavourable situation.[101] Kipling argued that even before 1914, Germany's larger economy and higher birth rate had made that country stronger than France; with much of France devastated by war and the French suffering heavy losses meant that its low birth rate would give it trouble, while Germany was mostly undamaged and still with a higher birth rate. So he reasoned that the future would bring German domination if Versailles were revised in Germany's favour, and it was madness for Britain to press France to do so.[101]

In 1924, Kipling was opposed to the Labour government of Ramsay MacDonald as "Bolshevism without bullets." He believed that Labour was a communist front organisation, and "excited orders and instructions from Moscow" would expose Labour as such to the British people.[102] Kipling's views were on the right. Though he admired Benito Mussolini to some extent in the 1920s, he was against fascism, calling Oswald Mosley was "a bounder and an arriviste." By 1935, he was calling Mussolini a deranged and dangerous egomaniac and in 1933 wrote, "The Hitlerites are out for blood." [103]

Despite his anti-communism, the first major translations of Kipling into Russian took place under Lenin's rule in the early 1920s, and Kipling was popular with Russian readers in the interwar period. Many younger Russian poets and writers, such as Konstantin Simonov, were influenced by him.[104] Kipling's clarity of style, use of colloquial language and employment of rhythm and rhyme were seen as major innovations in poetry that appealed to many younger Russian poets.[105] Though it was obligatory for Soviet journals to begin translations of Kipling with an attack on him as a "fascist" and an "imperialist," such was Kipling's popularity with Russian readers that his works were not banned in the Soviet Union until 1939, with the signing of the Molotov–Ribbentrop Pact.[104] The ban was lifted in 1941 after Operation Barbarossa, when Britain become a Soviet ally, but imposed for good with the Cold War in 1946.[106]

Many older editions of Rudyard Kipling's books have a swastika printed on the cover, associated with a picture of an elephant carrying a lotus flower, reflecting the influence of Indian culture. Kipling's use of the swastika was based on the Indian sun symbol conferring good luck and the Sanskrit word meaning "fortunate" or "well-being."[107] He used the swastika symbol in both right and left-facing forms, and it was in general use by others at the time.[108][109]

In a note to Edward Bok after the death of Lockwood Kipling in 1911, Rudyard said: "I am sending with this for your acceptance, as some little memory of my father to whom you were so kind, the original of one of the plaques that he used to make for me. I thought it being the Swastika would be appropriate for your Swastika. May it bring you even more good fortune."[107] Once the Nazis came to power and usurped the swastika, Kipling ordered that it should no longer adorn his books.[107] Less than a year before his death, Kipling gave a speech (titled "An Undefended Island") to the Royal Society of St George on 6 May 1935, warning of the danger which Nazi Germany posed to Britain.[110]

Kipling scripted the first Royal Christmas Message, delivered via the BBC's Empire Service by George V in 1932.[111][112] In 1934, he published a short story in The Strand Magazine, "Proofs of Holy Writ," postulating that William Shakespeare had helped to polish the prose of the King James Bible.[113]

Death

Kipling kept writing until the early 1930s, but at a slower pace and with less success than before. On the night of 12 January 1936, he suffered a haemorrhage in his small intestine. He underwent surgery, but died at Middlesex Hospital less than a week later on 18 January 1936, at the age of 70, of a perforated duodenal ulcer.[114][115][116] His death had previously been incorrectly announced in a magazine, to which he wrote, "I've just read that I am dead. Don't forget to delete me from your list of subscribers."[117]

The pallbearers at the funeral included Kipling's cousin, Prime Minister Stanley Baldwin, and the marble casket was covered by a Union Jack.[118] Kipling was cremated at Golders Green Crematorium in north-west London, and his ashes interred at Poets' Corner, part of the South Transept of Westminster Abbey, next to the graves of Charles Dickens and Thomas Hardy.[118] Kipling's will was proven on 6 April, with his estate valued at £168,141 2s. 11d. (roughly equivalent to £11,508,703 in 2019[119]).[120]

Legacy

In 2010, the International Astronomical Union approved the naming of a crater on the planet Mercury after Kipling – one of ten newly discovered impact craters observed by the MESSENGER spacecraft in 2008–2009.[121] In 2012, an extinct species of crocodile, Goniopholis kiplingi, was named in his honour "in recognition for his enthusiasm for natural sciences." [122]

More than 50 unpublished poems by Kipling, discovered by the American scholar Thomas Pinney, were released for the first time in March 2013.[123]

Kipling's writing has strongly influenced that of others. His stories for adults remain in print and have garnered high praise from writers as different as Poul Anderson, Jorge Luis Borges, and Randall Jarrell, who wrote: "After you have read Kipling's fifty or seventy-five best stories you realize that few men have written this many stories of this much merit, and that very few have written more and better stories."[124]

His children's stories remain popular and his Jungle Books made into several films. The first was made by producer Alexander Korda. Other films have been produced by The Walt Disney Company. A number of his poems were set to music by Percy Grainger. A series of short films based on some of his stories was broadcast by the BBC in 1964.[125] Kipling's work is still popular today.

The poet T. S. Eliot edited A Choice of Kipling's Verse (1941) with an introductory essay.[126] Eliot was aware of the complaints that had been levelled against Kipling and he dismissed them one by one: that Kipling is "a Tory" using his verse to transmit right wing political views, or "a journalist" pandering to popular taste; while Eliot writes: "I cannot find any justification for the charge that he held a doctrine of race superiority."[127] Eliot finds instead:

An immense gift for using words, an amazing curiosity and power of observation with his mind and with all his senses, the mask of the entertainer, and beyond that a queer gift of second sight, of transmitting messages from elsewhere, a gift so disconcerting when we are made aware of it that thenceforth we are never sure when it is not present: all this makes Kipling a writer impossible wholly to understand and quite impossible to belittle.

— T.S. Eliot[128]

Of Kipling's verse, such as his Barrack-Room Ballads, Eliot writes "of a number of poets who have written great poetry, only... a very few whom I should call great verse writers. And unless I am mistaken, Kipling's position in this class is not only high, but unique."[129]

In response to Eliot, George Orwell wrote a long consideration of Kipling's work for Horizon in 1942, noting that although as a "jingo imperialist" Kipling was "morally insensitive and aesthetically disgusting," his work had many qualities which ensured that while "every enlightened person has despised him... nine-tenths of those enlightened persons are forgotten and Kipling is in some sense still there.":

One reason for Kipling's power [was] his sense of responsibility, which made it possible for him to have a world-view, even though it happened to be a false one. Although he had no direct connexion with any political party, Kipling was a Conservative, a thing that does not exist nowadays. Those who now call themselves Conservatives are either Liberals, Fascists or the accomplices of Fascists. He identified himself with the ruling power and not with the opposition. In a gifted writer this seems to us strange and even disgusting, but it did have the advantage of giving Kipling a certain grip on reality. The ruling power is always faced with the question, 'In such and such circumstances, what would you do?', whereas the opposition is not obliged to take responsibility or make any real decisions. Where it is a permanent and pensioned opposition, as in England, the quality of its thought deteriorates accordingly. Moreover, anyone who starts out with a pessimistic, reactionary view of life tends to be justified by events, for Utopia never arrives and 'the gods of the copybook headings', as Kipling himself put it, always return. Kipling sold out to the British governing class, not financially but emotionally. This warped his political judgement, for the British ruling class were not what he imagined, and it led him into abysses of folly and snobbery, but he gained a corresponding advantage from having at least tried to imagine what action and responsibility are like. It is a great thing in his favour that he is not witty, not 'daring', has no wish to épater les bourgeois. He dealt largely in platitudes, and since we live in a world of platitudes, much of what he said sticks. Even his worst follies seem less shallow and less irritating than the 'enlightened' utterances of the same period, such as Wilde's epigrams or the collection of cracker-mottoes at the end of Man and Superman.

— George Orwell[130]

In 1939, the poet W.H. Auden celebrated Kipling in a similarly ambiguous way in his elegy for William Butler Yeats. Auden deleted this section from more recent editions of his poems.

Time, that is intolerant

Of the brave and innocent,

And indifferent in a week

To a beautiful physique,

Worships language, and forgives

Everyone by whom it lives;

Pardons cowardice, conceit,

Lays its honours at his feet.

Time, that with this strange excuse,

Pardons Kipling and his views,

And will pardon Paul Claudel,

Pardons him for writing well.[131]

The poet Alison Brackenbury writes "Kipling is poetry's Dickens, an outsider and journalist with an unrivalled ear for sound and speech."[132]

The English folk singer Peter Bellamy was a lover of Kipling's poetry, much of which he believed to have been influenced by English traditional folk forms. He recorded several albums of Kipling's verse set to traditional airs, or to tunes of his own composition written in traditional style.[133] However, in the case of the bawdy folk song, "The Bastard King of England," which is commonly credited to Kipling, it is believed that the song is actually misattributed.[134]

Kipling often is quoted in discussions of contemporary British political and social issues. In 1911, Kipling wrote the poem "The Reeds of Runnymede" that celebrated Magna Carta, and summoned up a vision of the "stubborn Englishry" determined to defend their rights. In 1996, the following verses of the poem were quoted by former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher warning against the encroachment of the European Union on national sovereignty:

At Runnymede, at Runnymede,

Oh, hear the reeds at Runnymede:

‘You musn’t sell, delay, deny,

A freeman’s right or liberty.

It wakes the stubborn Englishry,

We saw ’em roused at Runnymede!

… And still when Mob or Monarch lays

Too rude a hand on English ways,

The whisper wakes, the shudder plays,

Across the reeds at Runnymede.

And Thames, that knows the mood of kings,

And crowds and priests and suchlike things,

Rolls deep and dreadful as he brings

Their warning down from Runnymede![135]

Political singer-songwriter Billy Bragg, who attempts to build a left-wing English nationalism in contrast with the more common right-wing English nationalism, has attempted to 'reclaim' Kipling for an inclusive sense of Englishness.[136] Kipling's enduring relevance has been noted in the United States, as it has become involved in Afghanistan and other areas about which he wrote.[137][138][139]

Links with camping and scouting

In 1903, Kipling gave permission to Elizabeth Ford Holt to borrow themes from the Jungle Books to establish Camp Mowglis, a summer camp for boys on the shores of Newfound Lake in New Hampshire. Throughout their lives, Kipling and his wife Carrie maintained an active interest in Camp Mowglis, which still continues the traditions that Kipling inspired. Buildings at Mowglis have names such as Akela, Toomai, Baloo, and Panther. The campers are referred to as "the Pack," from the youngest "Cubs" to the oldest living in "Den."[140]

Kipling's links with the Scouting movements were also strong. Robert Baden-Powell, founder of Scouting, used many themes from Jungle Book stories and Kim in setting up his junior Wolf Cubs. These ties still exist, such as the popularity of "Kim's Game." The movement is named after Mowgli's adopted wolf family, and adult helpers of Wolf Cub Packs take names from The Jungle Book, especially the adult leader called Akela after the leader of the Seeonee wolf pack.[141]

Kipling's Burwash home

After the death of Kipling's wife in 1939, his house, Bateman's in Burwash, East Sussex, where he had lived from 1902 until 1936, was bequeathed to the National Trust. It is now a public museum dedicated to the author. Elsie Bambridge, his only child who lived to maturity, died childless in 1976, and bequeathed her copyrights to the National Trust, which in turn donated them to the University of Sussex to ensure better public access.[143]

Novelist and poet Sir Kingsley Amis wrote a poem, "Kipling at Bateman's," after visiting Burwash (where Amis's father lived briefly in the 1960s) as part of a BBC television series on writers and their houses.[144]

In 2003, actor Ralph Fiennes read excerpts from Kipling's works from the study in Bateman's, including The Jungle Book, Something of Myself, Kim, and The Just So Stories, and poems, including "If ..." and "My Boy Jack," for a CD published by the National Trust.[145][146]

Reputation in India

In modern-day India, whence he drew much of his material, Kipling's reputation remains controversial, especially among modern nationalists and some post-colonial critics. Rudyard Kipling was a prominent supporter of Colonel Reginald Dyer, who was responsible for the Jallianwala Bagh massacre in Amritsar (in the province of Punjab). Kipling called Dyer "the man who saved India" and initiated collections for the latter's homecoming prize.[147] However, Subhash Chopra writes in his book Kipling Sahib – the Raj Patriot that the benefit fund was started by The Morning Post newspaper, not by Kipling, and that Kipling made no contribution to the Dyer fund. While Kipling's name was conspicuously absent from the list of donors as published in The Morning Post, he clearly admired Dyer.[148]

Other contemporary Indian intellectuals such as Ashis Nandy have taken a more nuanced view. Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of independent India, often described Kipling's novel Kim as one of his favourite books.[149][150]

G.V. Desani, an Indian writer of fiction, had a more negative opinion of Kipling. He alludes to Kipling in his novel All About H. Hatterr:

I happen to pick up R. Kipling's autobiographical Kim. Therein, this self-appointed whiteman's burden-bearing sherpa feller's stated how, in the Orient, blokes hit the road and think nothing of walking a thousand miles in search of something.

Indian writer Khushwant Singh wrote in 2001 that he considers Kipling's "If—" "the essence of the message of The Gita in English," [151] referring to the Bhagavad Gita, an ancient Indian scripture. Indian writer R.K. Narayan said "Kipling, the supposed expert writer on India, showed a better understanding of the mind of the animals in the jungle than of the men in an Indian home or the marketplace."[152] The Indian politician and writer Sashi Tharoor commented "Kipling, that flatulent voice of Victorian imperialism, would wax eloquent on the noble duty to bring law to those without it".[153]

In November 2007, it was announced that Kipling's birth home in the campus of the J. J. School of Art in Mumbai would be turned into a museum celebrating the author and his works.[154]

Art

Though best known as an author, Kipling was also an accomplished artist. Influenced by Aubrey Beardsley, Kipling produced many illustrations for his stories, e.g. Just So Stories, 1919.[155]

Screen portrayals

- Reginald Sheffield portrayed Rudyard Kipling in Gunga Din (1939).

- Paul Scardon portrayed Rudyard Kipling in The Adventures of Mark Twain (1944).

- Christopher Plummer portrayed Rudyard Kipling in The Man Who Would Be King (1975).

- David Haig portrayed Rudyard Kipling in My Boy Jack (2007).

Bibliography

Kipling's bibliography includes fiction (including novels and short stories), non-fiction, and poetry. Several of his works were collaborations.

See also

- Kipling Trail

- List of Nobel laureates in Literature

- HMS Birkenhead (1845) – ship mentioned in one of Kipling's poems

References

- “Illustrations by Rudyard Kipling”. Victorian Web. Retrieved 1 October 2020

Cited sources

- Eliot, T.S. (1941). A Choice of Kipling's Verse, made by T. S. Eliot with an essay on Rudyard Kipling. Faber and Faber.[ISBN missing]

- Gilmour, David (2003). The long recessional: the imperial life of Rudyard Kipling. Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 978-1466830004.

- Hodgson, Katherine (October 1998). "The Poetry of Rudyard Kipling in Soviet Russia". The Modern Language Review. 93 (4): 1058–1071. doi:10.2307/3736277. JSTOR 3736277.

- Scott, David (June 2011). "Kipling, the Orient, and Orientals: 'Orientalism' Reoriented?". Journal of World History. 22 (2): 299–328 [315]. doi:10.1353/jwh.2011.0036. JSTOR 23011713. S2CID 143705079.

Further reading

- Biography and criticism

- Allen, Charles (2007). Kipling Sahib: India and the Making of Rudyard Kipling, Abacus. ISBN 978-0-349-11685-3

- Bauer, Helen Pike (1994). Rudyard Kipling: A Study of the Short Fiction. New York: Twayne

- Birkenhead, Lord (Frederick Smith, 2nd Earl of Birkenhead) (1978). Rudyard Kipling. Worthing: Littlehampton Book Services Ltd. ISBN 978-0-297-77535-5

- Carrington, Charles (1955). Rudyard Kipling: His Life and Work. London: Macmillan & Co.

- Croft-Cooke, Rupert (1948). Rudyard Kipling (London: Home & Van Thal Ltd.)

- David, C. (2007). Rudyard Kipling: a critical study, New Delhi: Anmol. ISBN 81-261-3101-2

- Dillingham, William B (2005). Rudyard Kipling: Hell and Heroism New York: Palgrave Macmillan[ISBN missing]

- Gilbert, Elliot L. ed. (1965). Kipling and the Critics (New York: New York University Press)

- Gilmour, David (2003). The Long Recessional: The Imperial Life of Rudyard Kipling New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux. ISBN 0-374-52896-9

- Green, Roger Lancelyn, ed. (1971). Kipling: the Critical Heritage. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

- Gross, John, ed. (1972). Rudyard Kipling: the Man, his Work and his World. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson

- Harris, Brian (2014). The Surprising Mr Kipling: An anthology and reassessment of the poetry of Rudyard Kipling. CreateSpace. ISBN 978-1-4942-2194-2

- Harris, Brian (2015). The Two Sided Man. CreateSpace. ISBN 1508712328.

- Kemp, Sandra (1988). Kipling's Hidden Narratives Oxford: Blackwell

- Lycett, Andrew (1999). Rudyard Kipling. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-81907-0

- Lycett, Andrew (ed.) (2010). Kipling Abroad, I. B. Tauris. ISBN 978-1-84885-072-9

- Mallett, Phillip (2003). Rudyard Kipling: A Literary Life Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan