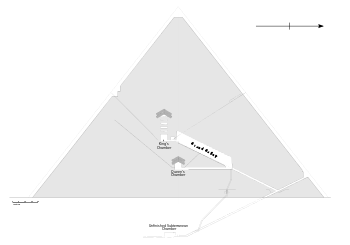

Looking carefully the pyramid in descript shows the evidence of the following:

1.) Gravestone

a. the category to the slate

b. example: Colma, California and/or the Presidio Cemetery

1. the dated to the slate as forma.) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/San_Francisco_National_Cemetery

2.) construction of such following the hidden in plain site. Quote insertion.

3.) Evidence (evidential (https://www.dictionary.com/browse/evidential?s=t ): Word category to be equated)

a. The Ten Commandments

b. Theology - Worldwide - Religion - Mythology

c. shape

Egyptian pyramids

Unicode: 𓍋𓅓𓂋𓉴 | ||||

| Pyramid in hieroglyphs |

|---|

The Egyptian pyramids are ancient pyramid-shaped masonry structures located in Egypt. As of November 2008, sources cite either 118 or 138 as the number of identified Egyptian pyramids.[1][2] Most were built as tombs for the country's pharaohs and their consorts during the Old and Middle Kingdom periods.[3][4][5]

The earliest known Egyptian pyramids are found at Saqqara, northwest of Memphis, although at least one step-pyramid-like structure has been found at Saqqara, dating to the First Dynasty: Mastaba 3808, which has been attributed to the reign of Pharaoh Anedjib, with inscriptions, and other archaeological remains of the period, suggesting there may have been others.[6] The otherwise earliest among these is the Pyramid of Djoser built c. 2630–2610 BC during the Third Dynasty.[7] This pyramid and its surrounding complex are generally considered to be the world's oldest monumental structures constructed of dressed masonry.[8]

The most famous Egyptian pyramids are those found at Giza, on the outskirts of Cairo. Several of the Giza pyramids are counted among the largest structures ever built.[9] The Pyramid of Khufu is the largest Egyptian pyramid. It is the only one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World still in existence.[10]

Historical development

The design of the Egyptian pyramid seems to have been a progression from the Sumerian ziggurat, a stepped pyramidal structure with a temple on top, which dated to as early as 4000–3500 BC.[11]

From the time of the Early Dynastic Period (c. 3150–2686 BC), Egyptians with sufficient means were buried in bench-like structures known as mastabas.[12][13] At Saqqara, Mastaba 3808, dating from the latter part of the 1st Dynasty, was discovered to contain a large, independently-built step-pyramid-like structure enclosed within the outer palace facade mastaba. Archaeological remains and inscriptions suggest there may have been other similar structures dating to this period.[14]

The first historically-documented Egyptian pyramid is attributed by Egyptologists to the 3rd Dynasty pharaoh Djoser. Although Egyptologists often credit his vizier Imhotep as its architect, the dynastic Egyptians themselves, contemporaneously or in numerous later dynastic writings about the character, did not credit him with either designing Djoser's pyramid or the invention of stone architecture.[15] The Pyramid of Djoser was first built as a square mastaba-like structure, which as a rule were known to otherwise be rectangular, and was expanded several times by way of a series of accretion layers, to produce the stepped pyramid structure we see today.[16] Egyptologists believe this design served as a gigantic stairway by which the soul of the deceased pharaoh could ascend to the heavens.[17]

Though other pyramids were attempted in the 3rd Dynasty after Djoser, it was the 4th Dynasty, transitioning from the step pyramid to true pyramid shape, which gave rise to the great pyramids of Meidum, Dahshur, and Giza. The last pharaoh of the 4th Dynasty, Shepseskaf, did not build a pyramid and beginning in the 5th Dynasty; for various reasons, the massive scale and precision of construction decreased significantly leaving these later pyramids smaller, less well-built, and often hastily constructed. By the end of the 6th Dynasty, pyramid building had largely ended and it was not until the Middle Kingdom that large pyramids were built again, though instead of stone, mudbrick was the main construction material.[18]

Long after the end of Egypt's own pyramid-building period, a burst of pyramid building occurred in what is present-day Sudan, after much of Egypt came under the rule of the Kingdom of Kush, which was then based at Napata. Napatan rule, known as the 25th Dynasty, lasted from 750 BCE to 664 BCE, and during that time Egyptian culture made an indelible impression on the Kushites. The Meroitic period of Kushite history, when the kingdom was centered on Meroë, (approximately in the period between 300 BCE and 300 CE), experienced a full-blown pyramid-building revival, which saw more than two hundred Egyptian-inspired indigenous royal pyramid-tombs constructed in the vicinity of the kingdom's capital cities.

Al-Aziz Uthman (1171–1198), the second Ayyubid Sultan of Egypt, tried to destroy the Giza pyramid complex. He gave up after only damaging the Pyramid of Menkaure because the task proved too large.[19]

Pyramid symbolism

The shape of Egyptian pyramids is thought to represent the primordial mound from which the Egyptians believed the earth was created. The shape of a pyramid is also thought to be representative of the descending rays of the sun, and most pyramids were faced with polished, highly reflective white limestone, in order to give them a brilliant appearance when viewed from a distance. Pyramids were often also named in ways that referred to solar luminescence. For example, the formal name of the Bent Pyramid at Dahshur was The Southern Shining Pyramid, and that of Senusret II at El Lahun was Senusret Shines.

While it is generally agreed that pyramids were burial monuments, there is continued disagreement on the particular theological principles that might have given rise to them. One suggestion is that they were designed as a type of "resurrection machine."[20]

The Egyptians believed the dark area of the night sky around which the stars appear to revolve was the physical gateway into the heavens. One of the narrow shafts that extend from the main burial chamber through the entire body of the Great Pyramid points directly towards the center of this part of the sky. This suggests the pyramid may have been designed to serve as a means to magically launch the deceased pharaoh's soul directly into the abode of the gods.[20]

All Egyptian pyramids were built on the west bank of the Nile, which, as the site of the setting sun, was associated with the realm of the dead in Egyptian mythology.[21]

Number and location of pyramids

In 1842, Karl Richard Lepsius produced the first modern list of pyramids – now known as the Lepsius list of pyramids – in which he counted 67. A great many more have since been discovered. As of November 2008, 118 Egyptian pyramids have been identified.[3] The location of Pyramid 29, which Lepsius called the "Headless Pyramid", was lost for a second time when the structure was buried by desert sands after Lepsius's survey. It was found again only during an archaeological dig conducted in 2008.[22]

Many pyramids are in a poor state of preservation or buried by desert sands. If visible at all, they may appear as little more than mounds of rubble. As a consequence, archaeologists are continuing to identify and study previously unknown pyramid structures.

The most recent pyramid to be discovered was that of Sesheshet at Saqqara, mother of the Sixth Dynasty pharaoh Teti, announced on 11 November 2008.[4][23]

All of Egypt's pyramids, except the small Third Dynasty pyramid at Zawyet el-Maiyitin, are sited on the west bank of the Nile, and most are grouped together in a number of pyramid fields. The most important of these are listed geographically, from north to south, below.

Abu Rawash

Abu Rawash is the site of Egypt's most northerly pyramid (other than the ruins of Lepsius pyramid number one),[5] the mostly ruined Pyramid of Djedefre, son and successor of Khufu. Originally it was thought that this pyramid had never been completed, but the current archaeological consensus is that not only was it completed, but that it was originally about the same size as the Pyramid of Menkaure, which would have placed it among the half-dozen or so largest pyramids in Egypt.

Its location adjacent to a major crossroads made it an easy source of stone. Quarrying, which began in Roman times, has left little apart from about fifteen courses of stone superimposed upon the natural hillock that formed part of the pyramid's core. A small adjacent satellite pyramid is in a better state of preservation.

Giza

The Giza Plateau is the location of the Pyramid of Khufu (also known as the "Great Pyramid" and the "Pyramid of Cheops"), the somewhat smaller Pyramid of Khafre (or Chephren), the relatively modest-sized Pyramid of Menkaure (or Mykerinus), along with a number of smaller satellite edifices known as "Queen's pyramids", and the Great Sphinx of Giza. Of the three, only Khafre's pyramid retains part of its original polished limestone casing, near its apex. This pyramid appears larger than the adjacent Khufu pyramid by virtue of its more elevated location, and the steeper angle of inclination of its construction – it is, in fact, smaller in both height and volume.

The Giza pyramid complex has been a popular tourist destination since antiquity and was popularized in Hellenistic times when the Great Pyramid was listed by Antipater of Sidon as one of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World. Today it is the only one of those wonders still in existence.

Zawyet el-Aryan

This site, halfway between Giza and Abusir, is the location for two unfinished Old Kingdom pyramids. The northern structure's owner is believed to be pharaoh Nebka, while the southern structure, known as the Layer Pyramid, may be attributable to the Third Dynasty pharaoh Khaba, a close successor of Sekhemkhet. If this attribution is correct, Khaba's short reign could explain the seemingly unfinished state of this step pyramid. Today it stands around 17 m (56 ft) high; had it been completed, it is likely to have exceeded 40 m (130 ft).

Abusir

There are a total of fourteen pyramids at this site, which served as the main royal necropolis during the Fifth Dynasty. The quality of construction of the Abusir pyramids is inferior to those of the Fourth Dynasty – perhaps signaling a decrease in royal power or a less vibrant economy. They are smaller than their predecessors, and are built of low-quality local limestone.

The three major pyramids are those of Niuserre, which is also the best preserved, Neferirkare Kakai and Sahure. The site is also home to the incomplete Pyramid of Neferefre. Most of the major pyramids at Abusir were built using similar construction techniques, comprising a rubble core surrounded by steps of mudbricks with a limestone outer casing. The largest of these Fifth Dynasty pyramids, the Pyramid of Neferirkare Kakai, is believed to have been built originally as a step pyramid some 70 m (230 ft) high and then later transformed into a "true" pyramid by having its steps filled in with loose masonry.

Saqqara

Major pyramids located here include the Pyramid of Djoser – generally identified as the world's oldest substantial monumental structure to be built of dressed stone – the Pyramid of Userkaf, the Pyramid of Teti and the Pyramid of Merikare, dating to the First Intermediate Period of Egypt. Also at Saqqara is the Pyramid of Unas, which retains a pyramid causeway that is one of the best-preserved in Egypt. Together with the pyramid of Userkaf, this pyramid was the subject of one of the earliest known restoration attempts, conducted by Khaemweset, a son of Ramesses II.[24] Saqqara is also the location of the incomplete step pyramid of Djoser's successor Sekhemkhet, known as the Buried Pyramid. Archaeologists believe that had this pyramid been completed, it would have been larger than Djoser's.

South of the main pyramid field at Saqqara is a second collection of later, smaller pyramids, including those of Pepi I, Djedkare Isesi, Merenre, Pepi II and Ibi. Most of these are in a poor state of preservation.

The Fourth Dynasty pharaoh Shepseskaf either did not share an interest in, or have the capacity to undertake pyramid construction like his predecessors. His tomb, which is also sited at south Saqqara, was instead built as an unusually large mastaba and offering temple complex. It is commonly known as the Mastabat al-Fir’aun.[25]

A previously unknown pyramid was discovered at north Saqqara in late 2008. Believed to be the tomb of Teti's mother, it currently stands approximately 5 m (16 ft) high, although the original height was closer to 14 m (46 ft).

Dahshur

This area is arguably the most important pyramid field in Egypt outside Giza and Saqqara, although until 1996 the site was inaccessible due to its location within a military base and was relatively unknown outside archaeological circles.

The southern Pyramid of Sneferu, commonly known as the Bent Pyramid, is believed to be the first Egyptian pyramid intended by its builders to be a "true" smooth-sided pyramid from the outset; the earlier pyramid at Meidum had smooth sides in its finished state, but it was conceived and built as a step pyramid, before having its steps filled in and concealed beneath a smooth outer casing of dressed stone. As a true smooth-sided structure, the Bent Pyramid was only a partial success – albeit a unique, visually imposing one; it is also the only major Egyptian pyramid to retain a significant proportion of its original smooth outer limestone casing intact. As such it serves as the best contemporary example of how the ancient Egyptians intended their pyramids to look. Several kilometres to the north of the Bent Pyramid is the last – and most successful – of the three pyramids constructed during the reign of Sneferu; the Red Pyramid is the world's first successfully completed smooth-sided pyramid. The structure is also the third largest pyramid in Egypt, after the pyramids of Khufu and Khafra at Giza.

Also at Dahshur is one of two pyramids built by Amenemhat III, known as the Black Pyramid, as well as a number of small, mostly ruined subsidiary pyramids.

Mazghuna

Located to the south of Dahshur, several mudbrick pyramids were built in this area in the late Middle Kingdom, perhaps for Amenemhat IV and Sobekneferu.

Lisht

Two major pyramids are known to have been built at Lisht: those of Amenemhat I and his son, Senusret I. The latter is surrounded by the ruins of ten smaller subsidiary pyramids. One of these subsidiary pyramids is known to be that of Amenemhat's cousin, Khaba II.[26] The site which is in the vicinity of the oasis of the Faiyum, midway between Dahshur and Meidum, and about 100 kilometres south of Cairo, is believed to be in the vicinity of the ancient city of Itjtawy (the precise location of which remains unknown), which served as the capital of Egypt during the Twelfth Dynasty.

Meidum

The pyramid at Meidum is one of three constructed during the reign of Sneferu, and is believed by some to have been started by that pharaoh's father and predecessor, Huni. However, that attribution is uncertain, as no record of Huni's name has been found at the site. It was constructed as a step pyramid and then later converted into the first "true" smooth-sided pyramid, when the steps were filled in and an outer casing added. The pyramid suffered several catastrophic collapses in ancient and medieval times. Medieval Arab writers described it as having seven steps, although today only the three uppermost of these remain, giving the structure its odd, tower-like appearance. The hill on which the pyramid is situated is not a natural landscape feature, it is the small mountain of debris created when the lower courses and outer casing of the pyramid gave way.

Hawara

Amenemhat III was the last powerful ruler of the Twelfth Dynasty, and the pyramid he built at Hawara, near the Faiyum, is believed to post-date the so-called "Black Pyramid" built by the same ruler at Dahshur. It is the Hawara pyramid that is believed to have been Amenemhet's final resting place.

El Lahun

The Pyramid of Senusret II at El Lahun is the southernmost royal-tomb pyramid structure in Egypt. Its builders reduced the amount of work necessary to construct it by using as its foundation and core a 12-meter-high natural limestone hill.

El-Kurru

Piye, the king of Kush who became the first ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, built a pyramid at El-Kurru. He was the first Egyptian pharaoh to be buried in a pyramid in centuries.

Nuri

Taharqa, a Kushite ruler of the Twenty-fifth Dynasty, built his pyramid at Nuri. It was the largest in the area (North Sudan).

Construction dates and heights

The following table lays out the chronology of the construction of most of the major pyramids mentioned here. Each pyramid is identified through the pharaoh who ordered it built, his approximate reign, and its location.

| Pyramid / Pharaoh | Reign | Field | Height |

|---|---|---|---|

| Djoser | c. 2670 BC | Saqqara | 62 meters (203 feet) |

| Sneferu | c. 2612–2589 BC | Dashur | 104 meters (341 feet) |

| Sneferu | c. 2612–2589 BC | Meidum | 65 meters (213 feet) (ruined)

*Would have been 91.65 meters (301 feet) or 175 Egyptian Royal cubits. |

| Khufu | c. 2589–2566 BC | Giza | 146.7 meters (481 feet) or 280 Egyptian Royal cubits |

| Djedefre | c. 2566–2558 BC | Abu Rawash | 60 meters (197 feet) |

| Khafre | c. 2558–2532 BC | Giza | 136.4 meters (448 feet)

*Originally: 143.5 m or 471 feet or 274 Egyptian Royal cubits |

| Menkaure | c. 2532–2504 BC | Giza | 65 meters (213 feet) or 125 Egyptian Royal cubits |

| Userkaf | c. 2494–2487 BC | Saqqara | 48 meters (161 feet) |

| Sahure | c. 2487–2477 BC | Abusir | 47 meters (155 feet) |

| Neferirkare Kakai | c. 2477–2467 BC | Abusir | 72.8 meters (239 feet) |

| Nyuserre Ini | c. 2416–2392 BC | Abusir | 51.68 m (169.6 feet) or 99 Egyptian Royal cubits |

| Amenemhat I | c. 1991–1962 BC | Lisht | 55 meters (181 feet) |

| Senusret I | c. 1971–1926 BC | Lisht | 61.25 meters (201 feet) |

| Senusret II | c. 1897–1878 BC | el-Lahun | 48.65 m (159.6 ft; 93 Egyptian Royal cubits) or

47.6 m (156 ft; 91 Egyptian Royal cubits) |

| Amenemhat III | c. 1860–1814 BC | Hawara | 75 meters (246 feet) |

| Khendjer | c. 1764–1759 BC | Saqqara | 37.35 m (122.5 feet), now 1 m (3.3 feet) |

| Piye | c. 721 BC | El-Kurru | 20 meters (66 feet) or

30 meters (99 feet) |

| Taharqa | c. 664 BC | Nuri | 40 meters (132 feet) or

50 meters (164 feet) |

Construction techniques

Constructing the pyramids involved moving huge quantities of stone. In 2013, papyri discovered at the Egyptian desert near the Red Sea by archaeologist Pierre Tallet revealed the Diary of Merer, an official of Egypt involved in transporting limestone along the Nile River. These papyri reveal processes in the building of the Great Pyramid at Giza, the tomb of the Pharaoh Khufu, just outside modern Cairo.[28]

Rather than overland transport of the limestone used in building the pyramid, there is evidence—in the Diary of Merer and from preserved remnants of ancient canals and transport boats—that limestone blocks were transported along the Nile River.[29] It is possible that quarried blocks were then transported to the construction site by wooden sleds, with sand in front of the sled wetted to reduce friction. Droplets of water created bridges between the grains of sand, helping them stick together.[30]

See also

- Al Ahram (Arabic for "the pyramids"), name of Egyptian newspaper

- Pyramidion

List

References

- "Solved! How Ancient Egyptians Moved Massive Pyramid Stones". Live Science. Retrieved 26 February 2018.

Bibliography

- Edwards, I. E. S., The Pyramids of Egypt Penguin Books Ltd; New edition (5 December 1991), ISBN 978-0-14-013634-0

- Lehner, Mark, The Complete Pyramids, Thames & Hudson, 1997, ISBN 978-0-500-05084-2

- Mendelssohn, Kurt, The Riddle of the Pyramids, Thames & Hudson Ltd (6 May 1974), ISBN 978-0-500-05015-6

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Pyramids of Egypt. |

- Ancient Egyptians from BBC History

- Pyramids World Heritage Site in panographies – 360-degree interactive imaging

- The Pyramids of Egypt – The meaning and construction of the Egyptian pyramids by Egyptologist Professor Nabil S welim.

- Ancient Authors – A site that quotes descriptions of the "Labyrinth" of Amenemhet III's pyramid at el-Lahun by various ancient authors.

- Ancient Egypt – History & Chronology – A site detailing the major pyramid sites of ancient Egypt and Nubia (Sudan).

Languages

The pyramid, which Hawass said was the 118th found in Egypt, was uncovered near the world's oldest pyramid at Saqqara, a burial ground for the rulers of ancient Egypt.

Deep below the Egyptian desert, archaeologists have found evidence of yet another pyramid, this one constructed 4,300 years ago to store the remains of a pharaoh’s mother. That makes 138 pyramids discovered here so far, and officials say they expect to find more.

The Great Pyramid...is still one of the largest structures ever raised by man, its plan twice the size of St. Peter's in Rome

A final echo of earlier practices is seen in the domain established by Djoser to supply his mortuary cult. He called it Hr-sb3-/mti-pt, "Horus, the foremost star in the sky". We could not wish for a clearer statement of the belief underlying the Step Pyramid: that it was a resurrection machine designed to propel its royal owner, Horus, to the pre-eminent place among the undying stars.

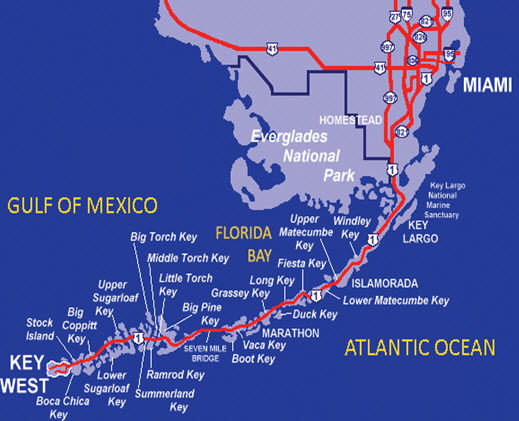

San Francisco National Cemetery

San Francisco National Cemetery looking north towards the Golden Gate Bridge. | |

| Details | |

|---|---|

| Established | 1884 |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| Coordinates | 37°47′59″N 122°27′52″WCoordinates: 37°47′59″N 122°27′52″W[1] |

| Type | U.S. National Cemetery |

| Size | 9 acres (3.6 ha) |

| No. of graves | 26,425 |

| Website | US Department of Veterans Affairs |

| Find a Grave | San Francisco National Cemetery |

San Francisco National Cemetery is a United States national cemetery, located in the Presidio of San Francisco, California. Because of the name and location, it is frequently confused with Golden Gate National Cemetery, a few miles south of the city.

About 1937, San Francisco residents voted to no longer build cemeteries within the city proper and, as a result, the site for a new national cemetery was selected south of the city limits. The cemetery is one of only four officially existing within San Francisco city limits (the others being the Columbarium of San Francisco, the historic graveyard next to Mission Dolores, and the sarcophagus of Thomas Starr King).

History

When Spain colonized what would become California, this area was selected as the site for a fort, or presidio, to defend San Francisco Bay. About 40 families traveled here from northern Mexico in 1776 and built the first settlement, a small quadrangle, only a few hundred feet west of what is now Funston Avenue. Mexico controlled the Presidio following 1821, but the fort became less important to the Mexican government. In 1835, most soldiers and their families moved north to Sonoma, leaving it nearly abandoned. During the Mexican–American War, U.S. troops occupied and repaired the damage to the fort.

The mid-century discovery of gold in California led to the sudden growth and importance of San Francisco, and prompted the U.S. government to establish a military reservation here. By executive order, President Millard Fillmore established the Presidio for military use in November 1850. During the 1850s and 1860s, Presidio-based soldiers fought Native Americans in California, Oregon, Washington, and Nevada. The outbreak of the American Civil War in 1861 re-emphasized the importance of California's riches and the military significance of San Francisco's harbor to the Union. This led, in 1862, to the first major construction and expansion program at the Presidio since its acquisition by the United States.

The Indian Wars of the 1870s and 1880s resulted in additional expansion of the Presidio, including large-scale tree planting and a post beautification program. By the following decade the Presidio had shed its frontier outpost appearance and was elevated to a major military installation and base for American expansion into the Pacific.

In 1890, with the creation of Sequoia, General Grant and Yosemite National Parks in the Sierra Nevada mountains of California, the protection of these scenic and natural resources was assigned to the U.S. cavalry stationed at the Presidio. Soldiers patrolled these parks during summer months until the start of World War I in 1914. The Spanish–American War in 1898 and subsequent Philippine–American War, from 1899 to 1902, increased the role of the Presidio. Thousands of troops camped in tent cities while awaiting shipment to the Philippines. Returning sick and wounded soldiers were treated in the Army's first permanent hospital, later renamed Letterman Army General Hospital. In 1914, troops under the command of General John Pershing departed the Presidio for the Mexican border in pursuit of Pancho Villa and his men.

When the United States entered World War II after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, Presidio soldiers dug foxholes along nearby beaches. Fourth Army Commander Gen. John L. DeWitt conducted the internment of thousands of Japanese and Japanese-Americans on the West Coast while U.S. soldiers of Japanese descent were trained to read and speak Japanese at the first Military Intelligence Service language school organized at Crissy Field. During the 1950s, the Presidio served as the headquarters for the Nike missile defense program and headquarters for the U.S. Sixth Army. The Presidio of San Francisco, encompassing more than 350 buildings with historic value, was designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962. In 1989, the Presidio closed as a military entity and was transferred to the National Park Service in October 1994.

On December 12, 1884, the War Department designated 9 acres (3.6 ha), including the site of the old post cemetery, as San Francisco National Cemetery. It was the first national cemetery established on the West Coast and marks the growth and development of a system of national cemeteries extending beyond the battlefields of the Civil War. Initial interments included the remains of the dead from the former post cemetery as well as individuals removed from cemeteries at abandoned forts and camps elsewhere along the Pacific coast and western frontier. In 1934, all unknown remains in the cemetery were disinterred and reinterred in one plot. Many soldiers and sailors who died overseas serving in the Philippines, China and other areas of the Pacific Theater are interred in San Francisco National Cemetery.

There are also three British Commonwealth service war graves here, a Canadian soldier of World War I, and a Royal Navy and Merchant Navy sailor of World War II.[2]

The cemetery is enclosed with a stone wall and slopes down a hill that today frames a view of the Golden Gate Bridge. Its original ornamental cast-iron entrance gates are present but have been unused since the entrance was relocated. Tall eucalyptus trees further enclose the cemetery. The lodge and rostrum date to the 1920s and reflect the Spanish Revival styling introduced to several western cemeteries.

Monuments and memorials

- A Grand Army of the Republic Memorial (1893)

- The Pacific Garrison Memorial (1897)

- Regular Army and Navy Union statue (1897)

- A monument to the Marines who died at the Tartar Wall in Peking, China (1900)

- A monument to the Unknown Dead (installed 1912 and relocated 1934)

Notable burials

Medal of Honor recipients

(Dates are of the actions for which they were awarded the Medal of Honor.)

- First Sergeant William Allen (Indian Campaigns), Company I, 23rd U.S. Infantry. Turret Mountain, Ariz., March 27, 1873 (Section OS, Grave 48-2).

- Chief Machinist's Mate William Badders U.S. Navy. At sea following sinking of the USS Squalus (SS-192), May 13, 1939 (Section A, Grave 788-A).

- Major James Coey (Civil War), 147th New York Infantry. Hatchers Run, Va., February 6, 1865 (Section OS, Grave 89-1).

- Sergeant James Congdon (served under the name James Madison) (Civil War), Company E, 8th New York Cavalry. Waynesboro, Va., March 2, 1865 (Section OSA, Grave 15-7).

- Second Lieutenant Matthias W. Day (Indian Campaigns), 9th U.S. Cavalry. Las Animas Canyon, N.M., September 18, 1879 (Section OS, Grave 2-11).

- Major General William F. Dean (Korean War), U.S. Army, commanding general, 24th Infantry Division. Taejon, Korea, July 20–21, 1950 (Section GHT, Grave 353-B).

- Captain Reginald B. Desiderio (Korean War), U.S. Army, commanding officer, Company E, 27th Infantry Regiment, 25th Infantry Division. Near Ipsok, Korea, November 27, 1950 (Section OS, Grave 128-20).

- Lieutenant Abraham DeSomer (Mexican Campaign), U.S. Navy, USS Utah (BB-31). Veracruz, Mexico, April 21–22, 1914 (Section MA, Grave 15).

- Colonel Kern W. Dunagan (Vietnam War), U.S. Army, Company A, 1st Battalion, 46th Infantry, Americal Division. Republic of Vietnam, May 13, 1969 (Section WS, Grave 117-I).

- Sergeant William Foster (Indian Campaigns), Company F, 4th U.S. Cavalry. Red River, Tex., September 29, 1872 (Section WS, Grave 197).

- Colonel Frederick Funston, Sr., (Philippine–American War), 20th Kansas Volunteer Infantry. Rio Grande de la Pampanga, Luzon, Philippine Islands, April 27, 1899 (Section OS, Grave 68-3).

- Seaman Rade Grbitch U.S. Navy. On board the USS Bennington (PG-4), July 21, 1905 (Section A, Grave 44).

- Major Oliver D. Greene (Civil War), U.S. Army. Antietam, Md., September 17, 1862 (Section OS, Grave 49-8).

- First Lieutenant John Chowning Gresham (Indian Campaigns), 7th U.S. Cavalry. Wounded Knee, S.D., December 29, 1890 (Section OS, Row 4-A Grave 5).

- Chief Carpenter's Mate Franz Anton Itrich (Spanish–American War), U.S. Navy. On board USS Petrel (PG-2), May 1, 1898 (Section OSA, Grave 83-5).

- Staff Sergeant Robert S. Kennemore (Korean War), U.S. Marine Corps, Company E, 2nd Battalion, 7th Marines, 1st Marine Division. North of Yudam-ni, Korea, November 27–28, 1950 (Section H, Grave CA- 404).

- Sergeant John Sterling Lawton (Indian Campaigns), Company D, 5th U.S. Cavalry. Milk River, Colo., September 29, 1879 (Section NAWS, Grave 1392).

- Private Cornelius J. Leahy (Philippine–American War), Company A, 36th Infantry, U.S. Volunteers. Near Porac, Luzon, Philippine Islands, September 3, 1899 (Section NA, Grave 970).

- First Sergeant John Mitchell (Indian Campaigns), Company I, 5th U.S. Infantry. Upper Washita, Tex., September 9–11, 1874 (Section NAWS, Grave 411).

- Private Albert Moore (Boxer Rebellion), U.S. Marine Corps. Peking, China, July 21 – August 17, 1900 (Section WS, Grave 1032-A).

- Second Lieutenant Louis Clinton Mosher (Philippine–American War), Philippine Scouts. Gagsak Mountain, Jolo, Philippine Islands, June 11, 1913 (Section NA, Gave 1408).

- Private Adam Neder (Indian Campaigns), Company A, 7th U.S. Cavalry. Sioux Campaign, December 1890 (Section NAWS, Grave 1805).

- First Lieutenant William R. Parnell (Indian Campaigns), 1st U.S. Cavalry. White Bird Canyon, Idaho, June 17, 1877 (Section OS, Grave 68-8).

- Corporal Reuben Jasper Phillips (Boxer Rebellion), U.S. Marine Corps. China, June 1900 (Section OSD, Grave 3).

- Corporal Norman W. Ressler (Spanish–American War), Company D, 17th U.S. Infantry. El Caney, Cuba, July 1, 1898 (Section WS, Grave 134-A).

- Sergeant Lloyd Martin Seibert (World War I), U.S. Army, Company F, 364th Infantry, 91st Division. Near Epinonville, France, September 26, 1918 (Section OS, Grave 128-10).

- First Lieutenant William Rufus Shafter (Civil War), Company I, 7th Michigan Infantry. Fair Oaks, Va., May 31, 1862 (Section OS, Grave 30-2).

- Private George Matthew Shelton, Sr., (Philippine–American War), Company I, 23rd U.S. Infantry. La Paz, Leyte, Philippine Islands, April 26, 1900 (Section OSD, Grave 799).

- Gunner's Mate Second Class Andrew V. Stoltenberg (Philippine–American War), U.S. Navy. Catbalogan, Samar, Philippine Islands, July 16, 1900 (Section A, Grave 242).

- Sergeant Bernard Taylor (Indian Campaigns), Company A, 5th U.S. Cavalry. Near Sunset Pass, Ariz., November 1, 1874 (Section WS, Grave 1090).

- Private William H. Thompkins (Spanish–American War), Troop G, 10th U.S. Cavalry. Battle of Tayacoba, Cuba, June 30, 1898 (Section WS, Grave 1036-A).

- Captain Charles A. Varnum (Indian Campaigns), Company B, 7th U.S. Cavalry. White Clay Creek, S.D., December 30, 1890 (Section OS, Grave 3-3-A).

- Second Lieutenant George W. Wallace (Philippine–American War), 9th U.S. Infantry. Tinuba, Luzon, Philippine Islands, March 4, 1900 (Section OS, ROW 39A, Grave 1).

- Seaman Axel Westermark (Boxer Rebellion), U.S. Navy. Peking, China June 28 – August 17, 1900 (Section A, Grave 32).

- Sergeant William Wilson (Indian Campaigns), Company I, 4th U.S. Cavalry. Colorado Valley, Texas, March 28, 1872 (Section WS, Grave 527).

Other burials

Two unusual interments at San Francisco National Cemetery are "Major" Pauline Cushman and Sarah A. Bowman. Cushman's headstone bears the inscription "Pauline C. Fryer, Union Spy", but her real name was Harriet Wood. Born in the 1830s, she became a performer in Thomas Placide's show Varieties and took the name Pauline Cushman. She married theater musician Charles Dickinson in 1853, but after her husband died of illness related to his service for Union forces, she returned to the stage. During spring 1863, while performing in Louisville, Kentucky, she was asked by the provost marshal to gather information regarding local Confederate activity. From there she was sent to Nashville, where she had some success conveying information about troop strength and movements. In Nashville, she was also captured and nearly hanged as a spy. She returned to the stage in 1864, to lecture and sell her autobiography. Entertainer P.T. Barnum promoted her as the "Spy of the Cumberland" and through Barnum's practiced boostership she quickly gained fleeting fame. After spending the 1870s working the redwood logging camps, she remarried and moved to the Arizona Territory. By 1893 she was divorced, destitute and desperate; she applied for her first husband's military pension and returned to San Francisco, where she died from an overdose of narcotics allegedly taken to soothe her rheumatism. Members of the Grand Army of the Republic and Women's Relief Corps conducted a magnificent funeral for the former spy. "Major" Cushman's remains reside in Officer's Circle.

Also buried at San Francisco National Cemetery is Sarah Bowman, also known as "Great Western", a formidable woman over 6 feet (1.8 m) tall with red hair and a fondness for wearing pistols. Married to a soldier, she traveled with Zachary Taylor's troops in the Mexican–American War helping to care for the wounded, for which she earned a government pension. After her husband's death she had a variety of male companions and ran an infamous tavern and brothel in El Paso, Texas. Bowman left El Paso when she married her last husband. The two ended up at Fort Yuma, where she operated a boarding house until her death from a spider bite in 1866. She was given a full military funeral and was buried in the Fort Yuma Cemetery. Several years later her body was exhumed and reburied at San Francisco National Cemetery.

San Francisco National Cemetery is also the burial location of Brigadier General George G. Gatley, who commanded brigades and divisions in World War I, and was also well known as the father of actress Ann Harding.[3]

U.S. representatives Phillip Burton and Sala Burton are also buried in the cemetery.

References

- "Gen. Gatley, 55th Brigade Chief, is Dead". Nashville Tennessean. Nashville, TN. January 22, 1931. pp. 1, 3.

Further reading

- Culbertson, Judi; Randall, Tom (1989). "14: Military Cemeteries". Permanent Californians: an illustrated guide to the cemeteries of California. Chelsea, VT: Chelsea Green. pp. 221–231. ISBN 978-0930031213. OCLC 19322965.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to San Francisco National Cemetery. |

- San Francisco National Cemetery

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: San Francisco National Cemetery

- San Francisco National Cemetery List of Burials

- San Francisco National Cemetery at Find a Grave

![]() This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs website http://www.cem.va.gov/cems/nchp/sanfrancisco.asp.

This article incorporates public domain material from the United States Department of Veterans Affairs website http://www.cem.va.gov/cems/nchp/sanfrancisco.asp.

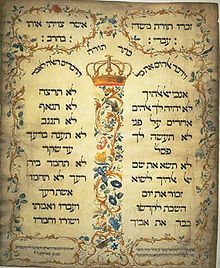

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Hebrew: עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְּרוֹת, Aseret ha'Dibrot; Arabic: وصايا عشر), also known as the Decalogue, are a set of biblical principles relating to ethics and worship. These are fundamental to both Judaism and Christianity. The text of the Ten Commandments appears twice in the Hebrew Bible: at Exodus 20:2–17 and Deuteronomy 5:6–17.

Modern scholarship has found likely influences in Hittite and Mesopotamian laws and treaties. Scholars disagree about when the Ten Commandments were recorded and by whom.

Terminology

In Biblical Hebrew, the Ten Commandments, called עשרת הדיברות (transliterated aseret ha-dibrot), are mentioned at Exodus 34:28.[1] and Deuteronomy 10:4.[2] In both sources, the terms are translatable as "the ten words", "the ten sayings", or "the ten matters".[3]

In the Septuagint (or LXX), the "ten words" was translated as "Decalogue", which is derived from Greek δεκάλογος, dekalogos, the latter meaning and referring[4] to the Greek translation (in accusative) δέκα λόγους, deka logous. This term is also sometimes used in English, in addition to Ten Commandments. The Tyndale and Coverdale English biblical translations used "ten verses". The Geneva Bible used "tenne commandements", which was followed by the Bishops' Bible and the Authorized Version (the "King James" version) as "ten commandments". Most major English versions use the word "commandments".[1]

The stone tablets, as opposed to the commandments inscribed on them, are called לוחות הברית, Lukhot HaBrit, meaning "the tablets of the covenant".

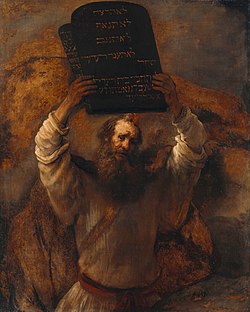

Biblical narrative

The biblical narrative of the revelation at Sinai begins in Exodus 19 after the arrival of the children of Israel at Mount Sinai (also called Horeb). On the morning of the third day of their encampment, "there were thunders and lightnings, and a thick cloud upon the mount, and the voice of the trumpet exceeding loud", and the people assembled at the base of the mount. After "the LORD[5] came down upon mount Sinai", Moses went up briefly and returned with stone tablets and prepared the people, and then in Exodus 20 "God spoke" to all the people the words of the covenant, that is, the "ten commandments"[6] as it is written. Modern biblical scholarship differs as to whether Exodus 19–20 describes the people of Israel as having directly heard all or some of the decalogue, or whether the laws are only passed to them through Moses.[7]

The people were afraid to hear more and moved "afar off", and Moses responded with "Fear not." Nevertheless, he drew near the "thick darkness" where "the presence of the Lord" was[8] to hear the additional statutes and "judgments",[9] all which he "wrote"[10] in the "book of the covenant"[11] which he read to the people the next morning, and they agreed to be obedient and do all that the LORD had said. Moses escorted a select group consisting of Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and "seventy of the elders of Israel" to a location on the mount where they worshipped "afar off"[12] and they "saw the God of Israel" above a "paved work" like clear sapphire stone.[13]

And the LORD said unto Moses, Come up to me into the mount, and be there: and I will give thee tablets of stone, and a law, and commandments which I have written; that thou mayest teach them. 13 And Moses rose up, and his minister Joshua: and Moses went up into the mount of God.

— First mention of the tablets in Exodus 24:12–13

The mount was covered by the cloud for six days, and on the seventh day Moses went into the midst of the cloud and was "in the mount forty days and forty nights."[14] And Moses said, "the LORD delivered unto me two tablets of stone written with the finger of God; and on them was written according to all the words, which the LORD spake with you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly."[15] Before the full forty days expired, the children of Israel collectively decided that something had happened to Moses, and compelled Aaron to fashion a golden calf, and he "built an altar before it"[16] and the people "worshipped" the calf.[17]

After the full forty days, Moses and Joshua came down from the mountain with the tablets of stone: "And it came to pass, as soon as he came nigh unto the camp, that he saw the calf, and the dancing: and Moses' anger waxed hot, and he cast the tablets out of his hands, and brake them beneath the mount."[18] After the events in chapters 32 and 33, the LORD told Moses, "Hew thee two tablets of stone like unto the first: and I will write upon these tablets the words that were in the first tablets, which thou brakest."[19] "And he wrote on the tablets, according to the first writing, the ten commandments, which the LORD spake unto you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly: and the LORD gave them unto me."[20] These tablets were later placed in the ark of the covenant.[21]

Numbering

Though both the Masoretic Text and the Dead Sea Scrolls show the passages of Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 divided into ten specific commandments with spaces between them,[22][23] many Modern English Bible translations give the appearance of more than ten imperative statements in each passage.

Different religious traditions divide the seventeen verses of Exodus 20:1–17 and their parallels in Deuteronomy 5:4–21 into ten commandments in different ways, shown in the table below. Some suggest that the number ten is a choice to aid memorization rather than a matter of theology.[24][25]

- All scripture quotes above are from the King James Version unless otherwise stated.

Traditions:

- T: Jewish Talmud, makes the "prologue" the first "saying" or "matter" and combines the prohibition on worshiping deities other than Yahweh with the prohibition on idolatry.

- R: Reformed Christians follow John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion, which follows the Septuagint; this system is also used in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.[50]

- LXX: Septuagint, generally followed by Orthodox Christians.

- P: Philo, same as the Septuagint, but with the prohibitions on killing and adultery reversed.

- L: Lutherans follow Luther's Large Catechism, which follows Augustine but subordinates the prohibition of images to the sovereignty of God in the First Commandment[51] and uses the word order of Exodus 20:17 rather than Deuteronomy 5:21 for the ninth and tenth commandments.

- S: Samaritan Pentateuch, with an additional commandment about Mount Gerizim as 10th.

- A: Augustine follows the Talmud in combining verses 3–6, but omits the prologue as a commandment and divides the prohibition on coveting in two and following the word order of Deuteronomy 5:21 rather than Exodus 20:17.

- C: Catechism of the Catholic Church, largely follows Augustine.

Religious interpretations

The Ten Commandments concern matters of fundamental importance in Judaism and Christianity: the greatest obligation (to worship only God), the greatest injury to a person (murder), the greatest injury to family bonds (adultery), the greatest injury to commerce and law (bearing false witness), the greatest inter-generational obligation (honour to parents), the greatest obligation to community (truthfulness), the greatest injury to movable property (theft).[52]

The Ten Commandments are written with room for varying interpretation, reflecting their role as a summary of fundamental principles.[25][52][53][54] They are not as explicit[52] or as detailed as rules[55] or as many other biblical laws and commandments, because they provide guiding principles that apply universally, across changing circumstances. They do not specify punishments for their violation. Their precise import must be worked out in each separate situation.[55]

The Bible indicates the special status of the Ten Commandments among all other Torah laws in several ways:

- They have a uniquely terse style.[56]

- Of all the biblical laws and commandments, the Ten Commandments alone[56] are said to have been "written with the finger of God" (Exodus 31:18).

- The stone tablets were placed in the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:21, Deuteronomy 10:2,5).[56]

Judaism

The Ten Commandments form the basis of Jewish law,[57] stating God's universal and timeless standard of right and wrong – unlike the rest of the 613 commandments in the Torah, which include, for example, various duties and ceremonies such as the kashrut dietary laws, and now unobservable rituals to be performed by priests in the Holy Temple.[58] Jewish tradition considers the Ten Commandments the theological basis for the rest of the commandments. Philo, in his four-book work The Special Laws, treated the Ten Commandments as headings under which he discussed other related commandments.[59] Similarly, in The Decalogue he stated that "under [the "commandment… against adulterers"] many other commands are conveyed by implication, such as that against seducers, that against practisers of unnatural crimes, that against all who live in debauchery, that against all men who indulge in illicit and incontinent connections."[60] Others, such as Rabbi Saadia Gaon, have also made groupings of the commandments according to their links with the Ten Commandments.[61]

According to Conservative Rabbi Louis Ginzberg, Ten Commandments are virtually entwined, in that the breaking of one leads to the breaking of another. Echoing an earlier rabbinic comment found in the commentary of Rashi to the Songs of Songs (4:5) Ginzberg explained—there is also a great bond of union between the first five commandments and the last five. The first commandment: "I am the Lord, thy God," corresponds to the sixth: "Thou shalt not kill," for the murderer slays the image of God. The second: "Thou shalt have no strange gods before me," corresponds to the seventh: "Thou shalt not commit adultery," for conjugal faithlessness is as grave a sin as idolatry, which is faithlessness to God. The third commandment: "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord in vain," corresponds to the eighth: "Thou shalt not steal," for stealing result in false oath in God's name. The fourth: "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy," corresponds to the ninth: "Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor," for he who bears false witness against his neighbor commits as grave a sin as if he had borne false witness against God, saying that He had not created the world in six days and rested on the seventh day (the holy Sabbath). The fifth commandment: "Honor thy father and thy mother," corresponds to the tenth: "Covet not thy neighbor's wife," for one who indulges this lust produces children who will not honor their true father, but will consider a stranger their father.[62]

The traditional Rabbinical Jewish belief is that the observance of these commandments and the other mitzvot are required solely of the Jewish people and that the laws incumbent on humanity in general are outlined in the seven Noahide laws, several of which overlap with the Ten Commandments. In the era of the Sanhedrin transgressing any one of six of the Ten Commandments theoretically carried the death penalty, the exceptions being the First Commandment, honouring your father and mother, saying God's name in vain, and coveting, though this was rarely enforced due to a large number of stringent evidentiary requirements imposed by the oral law.[63]

Two tablets

The arrangement of the commandments on the two tablets is interpreted in different ways in the classical Jewish tradition. Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel says that each tablet contained five commandments, "but the Sages say ten on one tablet and ten on the other", that is, that the tablets were duplicates.[64] This can be compared to diplomatic treaties of the ancient Near East, in which a copy was made for each party.[65]

According to the Talmud, the compendium of traditional Rabbinic Jewish law, tradition, and interpretation, one interpretation of the biblical verse "the tablets were written on both their sides",[66] is that the carving went through the full thickness of the tablets, yet was miraculously legible from both sides.[67]

Use in Jewish ritual

The Mishna records that during the period of the Second Temple, the Ten Commandments were recited daily,[68] before the reading of the Shema Yisrael (as preserved, for example, in the Nash Papyrus, a Hebrew manuscript fragment from 150–100 BCE found in Egypt, containing a version of the ten commandments and the beginning of the Shema); but that this practice was abolished in the synagogues so as not to give ammunition to heretics who claimed that they were the only important part of Jewish law,[69][70] or to dispel a claim by early Christians that only the Ten Commandments were handed down at Mount Sinai rather than the whole Torah.[68]

In later centuries rabbis continued to omit the Ten Commandments from daily liturgy in order to prevent confusion among Jews that they are only bound by the Ten Commandments, and not also by many other biblical and Talmudic laws, such as the requirement to observe holy days other than the sabbath.[68]

Today, the Ten Commandments are heard in the synagogue three times a year: as they come up during the readings of Exodus and Deuteronomy, and during the festival of Shavuot.[68] The Exodus version is read in parashat Yitro around late January–February, and on the festival of Shavuot, and the Deuteronomy version in parashat Va'etchanan in August–September. In some traditions, worshipers rise for the reading of the Ten Commandments to highlight their special significance[68] though many rabbis, including Maimonides, have opposed this custom since one may come to think that the Ten Commandments are more important than the rest of the Mitzvot.[71]

In printed Chumashim, as well as in those in manuscript form, the Ten Commandments carry two sets of cantillation marks. The ta'am 'elyon (upper accentuation), which makes each Commandment into a separate verse, is used for public Torah reading, while the ta'am tachton (lower accentuation), which divides the text into verses of more even length, is used for private reading or study. The verse numbering in Jewish Bibles follows the ta'am tachton. In Jewish Bibles the references to the Ten Commandments are therefore Exodus 20:2–14 and Deuteronomy 5:6–18.

Samaritan

The Samaritan Pentateuch varies in the Ten Commandments passages, both in that the Samaritan Deuteronomical version of the passage is much closer to that in Exodus, and in that Samaritans count as nine commandments what others count as ten. The Samaritan tenth commandment is on the sanctity of Mount Gerizim.

The text of the Samaritan tenth commandment follows:[72]

And it shall come to pass when the Lord thy God will bring thee into the land of the Canaanites whither thou goest to take possession of it, thou shalt erect unto thee large stones, and thou shalt cover them with lime, and thou shalt write upon the stones all the words of this Law, and it shall come to pass when ye cross the Jordan, ye shall erect these stones which I command thee upon Mount Gerizim, and thou shalt build there an altar unto the Lord thy God, an altar of stones, and thou shalt not lift upon them iron, of perfect stones shalt thou build thine altar, and thou shalt bring upon it burnt offerings to the Lord thy God, and thou shalt sacrifice peace offerings, and thou shalt eat there and rejoice before the Lord thy God. That mountain is on the other side of the Jordan at the end of the road towards the going down of the sun in the land of the Canaanites who dwell in the Arabah facing Gilgal close by Elon Moreh facing Shechem.

Christianity

Most traditions of Christianity hold that the Ten Commandments have divine authority and continue to be valid, though they have different interpretations and uses of them.[73] The Apostolic Constitutions, which implore believers to "always remember the ten commands of God," reveal the importance of the Decalogue in the early Church.[74] Through most of Christian history the decalogue was considered a summary of God's law and standard of behaviour, central to Christian life, piety, and worship.[75]

References in the New Testament

During his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus explicitly referenced the prohibitions against murder and adultery. In Matthew 19:16–19 Jesus repeated five of the Ten Commandments, followed by that commandment called "the second" (Matthew 22:34–40) after the first and great commandment.

And, behold, one came and said unto him, Good Master, what good thing shall I do, that I may have eternal life? And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments. He saith unto him, Which? Jesus said, Thou shalt do no murder, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness, Honour thy father and thy mother: and, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul the Apostle also mentioned five of the Ten Commandments and associated them with the neighbourly love commandment.

Romans 13:8 Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law.

9 For this, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not kill, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness, Thou shalt not covet; and if there be any other commandment, it is briefly comprehended in this saying, namely, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

10 Love worketh no ill to his neighbour: therefore love is the fulfilling of the law.— Romans 13:8–10 KJV

Catholicism

In Catholicism, Jesus freed Christians from the rest of Jewish religious law, but not from their obligation to keep the Ten Commandments.[76] It has been said that they are to the moral order what the creation story is to the natural order.[76]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church—the official exposition of the Catholic Church's Christian beliefs—the Commandments are considered essential for spiritual good health and growth,[77] and serve as the basis for social justice.[78] Church teaching of the Commandments is largely based on the Old and New Testaments and the writings of the early Church Fathers.[79] In the New Testament, Jesus acknowledged their validity and instructed his disciples to go further, demanding a righteousness exceeding that of the scribes and Pharisees.[80] Summarized by Jesus into two "great commandments" that teach the love of God and love of neighbour,[81] they instruct individuals on their relationships with both.

Orthodox

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds its moral truths to be chiefly contained in the Ten Commandments.[82] A confession begins with the Confessor reciting the Ten Commandments and asking the penitent which of them he has broken.[83]

Protestantism

After rejecting the Roman Catholic moral theology, giving more importance to biblical law and the gospel, early Protestant theologians continued to take the Ten Commandments as the starting point of Christian moral life.[84] Different versions of Christianity have varied in how they have translated the bare principles into the specifics that make up a full Christian ethic.[84]

Lutheranism

The Lutheran division of the commandments follows the one established by St. Augustine, following the then current synagogue scribal division. The first three commandments govern the relationship between God and humans, the fourth through eighth govern public relationships between people, and the last two govern private thoughts. See Luther's Small Catechism[85] and Large Catechism.[51]

Reformed

The Articles of the Church of England, Revised and altered by the Assembly of Divines, at Westminster, in the year 1643 state that "no Christian man whatsoever is free from the obedience of the commandments which are called moral. By the moral law, we understand all the Ten Commandments taken in their full extent."[86] The Westminster Confession, held by Presbyterian Churches, holds that the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments "does forever bind all, as well justified persons as others, to the obedience thereof".[87]

Methodist

The moral law contained in the Ten Commandments, according to the founder of the Methodist movement John Wesley, was instituted from the beginning of the world and is written on the hearts of all people.[88] As with the Reformed view,[89] Wesley held that the moral law, which is contained in the Ten Commandments, stands today:[90]

Every part of this law must remain in force upon all mankind in all ages, as not depending either on time or place, nor on any other circumstances liable to change; but on the nature of God and the nature of man, and their unchangeable relation to each other" (Wesley's Sermons, Vol. I, Sermon 25).[90]

In keeping with Wesleyan covenant theology, "while the ceremonial law was abolished in Christ and the whole Mosaic dispensation itself was concluded upon the appearance of Christ, the moral law remains a vital component of the covenant of grace, having Christ as its perfecting end."[88] As such, in Methodism, an "important aspect of the pursuit of sanctification is the careful following" of the Ten Commandments.[89]

Baptist

The Ten Commandments are a summary of the requirements of a works covenant (called the "Old Covenant"), given on Mount Sinai to the nascent nation of Israel.[citation needed] The Old Covenant came to an end at the cross and is therefore not in effect.[citation needed] They do reflect the eternal character of God, and serve as a paragon of morality.[91]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

According to the doctrine of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jesus completed rather than rejected the Mosaic law.[92] The Ten Commandments are considered eternal gospel principles necessary for exaltation.[93] They appear in the Book of Mosiah 12:34–36,[94] 13:15–16,[95] 13:21–24[96] and Doctrine and Covenants.[93] According to the Book of Mosiah, a prophet named Abinadi taught the Ten Commandments in the court of King Noah and was martyred for his righteousness.[97] Abinadi knew the Ten Commandments from the brass plates.[98]

In an October 2011 address, the Church president and prophet Thomas S. Monson taught "The Ten Commandments are just that—commandments. They are not suggestions."[99] In that same talk he used small quotations listing the numbering and selection of the commandments. This and other sources[100] don't include the prologue, making it most consistent with the Septuagint numbering.

Islam

Moses and the Tablets

The receiving of the Ten Commandments by Prophet Musa (Moses) is dealt with in much detail in Islamic tradition[101] with the meeting of Moses with God on Mount Sinai described in Surah A'raf (7:142-145). The Revealing of the Tablets on which were the Commandments of God is described in the following verse:

And We wrote for him (Moses) on the Tablets the lesson to be drawn from all things and the explanation of all things (and said): Hold unto these with firmness, and enjoin your people to take the better therein. I shall show you the home of Al-Fasiqun (the rebellious, disobedient to Allah).[102]

The Tablets are further alluded to in verses 7:150, when Moses threw the Tablets down in anger at seeing the Israelites' worshipping of the golden calf, and in 7:154 when he picked up the Tablets having recovered from his anger:

And when the anger of Musa (Moses) was appeased, he took up the Tablets, and in their inscription was guidance and mercy for those who fear their Lord.[103]

Quranic reference to the ten commandments can be found in chapter 2 verses 83 and 84 "And [recall] when We took the covenant from the Children of Israel, [enjoining upon them], "Do not worship except Allah (1) ; and to parents do good (2) and to relatives (3), orphans (4), and the needy (5). And speak to people good words (6) and establish prayer (7) and give Zakat (8)." Then you turned away, except a few of you, and you were refusing." "And [recall] when We took your covenant, [saying], "Do not shed each other's blood (9) or evict one another from your homes (10)." Then you acknowledged [this] while you were witnessing"[citation needed]

Classical views

Three verses of Surah An'am (6:151-153) are widely taken to be a reinstatement (or revised version) of the Ten Commandments[104][105][106] either as revealed to Moses originally or as they are to be taken by Muslims now:[107]

151. Say: "Come, I will recite what your Lord has prohibited you from: 1Join not anything in worship with Him; 2And be good (and dutiful) to your parents; 3And kill not your children because of poverty - We provide sustenance for you and for them; 4And come not near to Al-Fawahish (shameful sins, illegal sexual intercourse, adultery etc.) whether committed openly or secretly, 5And kill not anyone whom Allah has forbidden, except for a just cause (according to the Law). This He has commanded you that you may understand.

152. "6And come not near to the orphan's property, except to improve it, until he (or she) attains the age of full strength; 7And give full measure and full weight with justice. We burden not any person, but that which he can bear. 8And whenever you give your word (i.e. judge between men or give evidence, etc.), say the truth even if a near relative is concerned, 9And fulfill the Covenant of Allah. This He commands you, that you may remember.

153. "10And verily, this (the Commandments mentioned in the above Verses) is my Straight Path, so follow it, and follow not (other) paths, for they will separate you away from His Path. This He has ordained for you that you may become Al-Muttaqun (the pious)."[108]

Evidence for these verses having some relation to Moses and the Ten Commandments is from the verse which immediately follows them:

Then, We gave Musa (Moses) the Book, to complete (Our Favour) upon those who would do right, and explaining all things in detail and a guidance and a mercy that they might believe in the meeting with their Lord.[109]

According to a narration in Mustadrak Hakim, Ibn Abbas, a prominent narrator of Israiliyat traditions said, "In Surah Al-An`am, there are clear Ayat, and they are the Mother of the Book (the Qur'an)." He then recited the above verses.[110]

Also in Mustadrak Hakim is the narration of Ubada ibn as-Samit:

The Messenger of Allah said, "Who among you will give me his pledge to do three things?"

He then recited the (above) Ayah (6:151-153).

He then said, "Whoever fulfills (this pledge), then his reward will be with Allah, but whoever fell into shortcomings and Allah punishes him for it in this life, then that will be his recompense. Whoever Allah delays (his reckoning) until the Hereafter, then his matter is with Allah. If He wills, He will punish him, and if He wills, He will forgive him."[110]

Ibn Kathir mentions a narration of Abdullah ibn Mas'ud in his Tafsir:

"Whoever wishes to read the will and testament of the Messenger of Allah on which he placed his seal, let him read these Ayat (6:151-153)."[111]

Other views

Main points of interpretative difference

Sabbath day

The Abrahamic religions observe the Sabbath in various ways. In Judaism it is observed on Saturday (reckoned from dusk to dusk). In Christianity, it is sometimes observed on Saturday, sometimes on Sunday, and sometimes not at all (non-Sabbatarianism). Observing the Sabbath on Sunday, the day of resurrection, gradually became the dominant Christian practice from the Jewish-Roman wars onward.[citation needed] The Church's general repudiation of Jewish practices during this period is apparent in the Council of Laodicea (4th century AD) where Canons 37–38 state: "It is not lawful to receive portions sent from the feasts of Jews or heretics, nor to feast together with them" and "It is not lawful to receive unleavened bread from the Jews, nor to be partakers of their impiety".[112] Canon 29 of the Laodicean council specifically refers to the sabbath: "Christians must not judaize by resting on the [Jewish] Sabbath, but must work on that day, rather honouring the Lord's Day; and, if they can, resting then as Christians. But if any shall be found to be judaizers, let them be anathema from Christ."[112]

Killing or murder

The image is from the altar screen of the Temple Church near the Law Courts in London.

Multiple translations exist of the fifth/sixth commandment; the Hebrew words לא תרצח (lo tirtzach) are variously translated as "thou shalt not kill" or "thou shalt not murder".[113]

The imperative is against unlawful killing resulting in bloodguilt.[114] The Hebrew Bible contains numerous prohibitions against unlawful killing, but does not prohibit killing in the context of warfare (1Kings 2:5–6), capital punishment (Leviticus 20:9–16) or a home invasion during the night (Exodus 22:2–3), which are considered justified. The New Testament is in agreement that murder is a grave moral evil,[115] and references the Old Testament view of bloodguilt.[116]

Theft

German Old Testament scholar Albrecht Alt: Das Verbot des Diebstahls im Dekalog (1953), suggested that the commandment translated as "thou shalt not steal" was originally intended against stealing people—against abductions and slavery, in agreement with the Talmudic interpretation of the statement as "thou shalt not kidnap" (Sanhedrin 86a).

Idolatry

In Judaism there is a prohibition against worshipping an idol or a representation of God, but there is no restriction on art or simple depictions. Islam has a stronger prohibition, banning representations of God, and in some cases of Muhammad, humans and, in some interpretations, any living creature.

In the non-canonical Gospel of Barnabas, it is claimed that Jesus stated that idolatry is the greatest sin as it divests a man fully of faith, and hence of God.[117] The words attributed to Jesus prohibit not only worshipping statues of wood or stone; but also statues of flesh. "...all which a man loves, for which he leaves everything else but that, is his god, thus the glutton and drunkard has for his idol his own flesh, the fornicator has for his idol the harlot and the greedy has for his idol silver and gold, and so the same for every other sinner."[118] Idolatory was thus the basic sin, which manifested in various acts or thoughts, which displace the primacy of God. However, the Gospel of Barnabas does not form part of the Christian bible. It is known only from 16th- and 17th-century manuscripts, and frequently reflects Islamic rather than Christian understandings,[119] so it cannot be taken as authoritative on Christian views.

In Christianity's earliest centuries, some Christians had informally adorned their homes and places of worship with images of Christ and the saints, which others thought inappropriate. No church council had ruled on whether such practices constituted idolatry. The controversy reached crisis level in the 8th century, during the period of iconoclasm: the smashing of icons,[citation needed] and again in the Middle Ages, becoming a critical point of contention in the Protestant Reformation.

In 726 Emperor Leo III ordered all images removed from all churches; in 730 a council forbade veneration of images, citing the Second Commandment; in 787 the Seventh Ecumenical Council reversed the preceding rulings, condemning iconoclasm and sanctioning the veneration of images; in 815 Leo V called yet another council, which reinstated iconoclasm; in 843 Empress Theodora again reinstated veneration of icons.[citation needed] This mostly settled the matter until the Reformation, when John Calvin declared that the ruling of the Seventh Ecumenical Council "emanated from Satan".[citation needed] Protestant iconoclasts at this time destroyed statues, pictures, stained glass, and artistic masterpieces.[citation needed]

The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates Theodora's restoration of the icons every year on the First Sunday of Great Lent.[citation needed] Eastern Orthodox tradition teaches that while images of God, the Father, remain prohibited, depictions of Jesus as the incarnation of God as a visible human are permissible. To emphasize the theological importance of the incarnation, the Orthodox Church encourages the use of icons in church and private devotions, but prefers a two-dimensional depiction[120] as a reminder of this theological aspect. Icons depict the spiritual dimension of their subject rather than attempting a naturalistic portrayal.[citation needed] In modern use (usually as a result of Roman Catholic influence), more naturalistic images and images of the Father, however, also appear occasionally in Orthodox churches, but statues, i.e. three-dimensional depictions, continue to be banned.[120]

Adultery

Originally this commandment forbade male Israelites from having sexual intercourse with the wife of another Israelite; the prohibition did not extend to their own slaves. Sexual intercourse between an Israelite man, married or not, and a woman who was neither married nor betrothed was not considered adultery.[121] This concept of adultery stems from the economic aspect of Israelite marriage whereby the husband has an exclusive right to his wife, whereas the wife, as the husband's possession, did not have an exclusive right to her husband.[122]

Louis Ginzberg argued that the tenth commandment (Covet not thy neighbor's wife) is directed against a sin which may lead to a trespassing of all Ten Commandments.[123]

Critical historical analysis

Early theories

Critical scholarship is divided over its interpretation of the ten commandment texts.

Julius Wellhausen's documentary hypothesis suggests that Exodus 20-23 and 34 "might be regarded as the document which formed the starting point of the religious history of Israel."[124] Deuteronomy 5 then reflects King Josiah's attempt to link the document produced by his court to the older Mosaic tradition.

In a 2002 analysis of the history of this position, Bernard M. Levinson argued that this reconstruction assumes a Christian perspective, and dates back to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's polemic against Judaism, which asserted that religions evolve from the more ritualistic to the more ethical. Goethe thus argued that the Ten Commandments revealed to Moses at Mount Sinai would have emphasized rituals, and that the "ethical" Decalogue Christians recite in their own churches was composed at a later date, when Israelite prophets had begun to prophesy the coming of the messiah. Levinson points out that there is no evidence, internal to the Hebrew Bible or in external sources, to support this conjecture. He concludes that its vogue among later critical historians represents the persistence of the idea that the supersession of Judaism by Christianity is part of a longer history of progress from the ritualistic to the ethical.[125]

By the 1930s, historians who accepted the basic premises of multiple authorship had come to reject the idea of an orderly evolution of Israelite religion. Critics instead began to suppose that law and ritual could be of equal importance, while taking different form, at different times. This means that there is no longer any a priori reason to believe that Exodus 20:2–17 and Exodus 34:10–28 were composed during different stages of Israelite history. For example, critical historian John Bright also dates the Jahwist texts to the tenth century BCE, but believes that they express a theology that "had already been normalized in the period of the Judges" (i.e., of the tribal alliance).[126] He concurs about the importance of the decalogue as "a central feature in the covenant that brought together Israel into being as a people"[127] but views the parallels between Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, along with other evidence, as reason to believe that it is relatively close to its original form and Mosaic in origin.[128]

Hittite treaties

According to John Bright, however, there is an important distinction between the Decalogue and the "book of the covenant" (Exodus 21-23 and 34:10–24). The Decalogue, he argues, was modelled on the suzerainty treaties of the Hittites (and other Mesopotamian Empires), that is, represents the relationship between God and Israel as a relationship between king and vassal, and enacts that bond.[129]

"The prologue of the Hittite treaty reminds his vassals of his benevolent acts.. (compare with Exodus 20:2 "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery"). The Hittite treaty also stipulated the obligations imposed by the ruler on his vassals, which included a prohibition of relations with peoples outside the empire, or enmity between those within."[130] (Exodus 20:3: "You shall have no other gods before Me"). Viewed as a treaty rather than a law code, its purpose is not so much to regulate human affairs as to define the scope of the king's power.[131]

Julius Morgenstern argued that Exodus 34 is distinct from the Jahwist document, identifying it with king Asa's reforms in 899 BCE.[132] Bright, however, believes that like the Decalogue this text has its origins in the time of the tribal alliance. The book of the covenant, he notes, bears a greater similarity to Mesopotamian law codes (e.g. the Code of Hammurabi which was inscribed on a stone stele). He argues that the function of this "book" is to move from the realm of treaty to the realm of law: "The Book of the Covenant (Ex., chs. 21 to 23; cf. ch. 34), which is no official state law, but a description of normative Israelite judicial procedure in the days of the Judges, is the best example of this process."[133] According to Bright, then, this body of law too predates the monarchy.[134]

Dating

Archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that "the astonishing composition came together … in the seventh century BCE".[135] An even later date (after 586 BCE) is suggested by David H. Aaron.[136]

The Ritual Decalogue

Some proponents of the Documentary hypothesis have argued that the biblical text in Exodus 34:28[137] identifies a different list as the ten commandments, that of Exodus 34:11–27.[138] Since this passage does not prohibit murder, adultery, theft, etc., but instead deals with the proper worship of Yahweh, some scholars call it the "Ritual Decalogue", and disambiguate the ten commandments of traditional understanding as the "Ethical Decalogue".[139][140][141][142]

According to these scholars the Bible includes multiple versions of events. On the basis of many points of analysis including linguistic it is shown as a patchwork of sources sometimes with bridging comments by the editor (Redactor) but otherwise left intact from the original, frequently side by side.[143]

Richard Elliott Friedman argues that the Ten Commandments at Exodus 20:1–17 "does not appear to belong to any of the major sources. It is likely to be an independent document, which was inserted here by the Redactor."[144] In his view, the Covenant Code follows that version of the Ten Commandments in the northern Israel E narrative. In the J narrative in Exodus 34 the editor of the combined story known as the Redactor (or RJE), adds in an explanation that these are a replacement for the earlier tablets which were shattered. "In the combined JE text, it would be awkward to picture God just commanding Moses to make some tablets, as if there were no history to this matter, so RJE adds the explanation that these are a replacement for the earlier tablets that were shattered."[145]

He writes that Exodus 34:14–26 is the J text of the Ten Commandments: "The first two commandments and the sabbath commandment have parallels in the other versions of the Ten Commandments. (Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5). … The other seven commandments here are completely different."[146] He suggests that differences in the J and E versions of the Ten Commandments story are a result of power struggles in the priesthood. The writer has Moses smash the tablets "because this raised doubts about the Judah's central religious shrine".[147]

According to Kaufmann, the Decalogue and the book of the covenant represent two ways of manifesting God's presence in Israel: the Ten Commandments taking the archaic and material form of stone tablets kept in the ark of the covenant, while the book of the covenant took oral form to be recited to the people.[148]

United States debate over display on public property

European Protestants replaced some visual art in their churches with plaques of the Ten Commandments after the Reformation. In England, such "Decalogue boards" also represented the English monarch's emphasis on rule of royal law within the churches. The United States Constitution forbids establishment of religion by law; however images of Moses holding the tablets of the Decalogue, along other religious figures including Solomon, Confucius, and Muhammad holding the Quran, are sculpted on the north and south friezes of the pediment of the Supreme Court building in Washington.[149] Images of the Ten Commandments have long been contested symbols for the relationship of religion to national law.[150]