Anaximander

Anaximander | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | c. 610 BC |

| Died | c. 546 BC |

| Era | Pre-Socratic philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | |

Main interests | Metaphysics, astronomy, geometry, geography |

Notable ideas | The apeiron is the arche Evolutionary view of living things[2][3] Earth floats unsupported Mechanical model of the sky Water of rain from evaporation |

Anaximander (/æˌnæksɪˈmændər/; Greek: Ἀναξίμανδρος Anaximandros; c. 610 – c. 546 BC), was a pre-Socratic Greek philosopher who lived in Miletus,[4] a city of Ionia (in modern-day Turkey). He belonged to the Milesian school and learned the teachings of his master Thales. He succeeded Thales and became the second master of that school where he counted Anaximenes and, arguably, Pythagoras amongst his pupils.[5]

Little of his life and work is known today. According to available historical documents, he is the first philosopher known to have written down his studies,[6] although only one fragment of his work remains. Fragmentary testimonies found in documents after his death provide a portrait of the man.

Anaximander was an early proponent of science and tried to observe and explain different aspects of the universe, with a particular interest in its origins, claiming that nature is ruled by laws, just like human societies, and anything that disturbs the balance of nature does not last long.[7] Like many thinkers of his time, Anaximander's philosophy included contributions to many disciplines. In astronomy, he attempted to describe the mechanics of celestial bodies in relation to the Earth. In physics, his postulation that the indefinite (or apeiron) was the source of all things led Greek philosophy to a new level of conceptual abstraction. His knowledge of geometry allowed him to introduce the gnomon in Greece. He created a map of the world that contributed greatly to the advancement of geography. He was also involved in the politics of Miletus and was sent as a leader to one of its colonies.

Biography

Anaximander, son of Praxiades, was born in the third year of the 42nd Olympiad (610 BC).[9] According to Apollodorus of Athens, Greek grammarian of the 2nd century BC, he was sixty-four years old during the second year of the 58th Olympiad (547–546 BC), and died shortly afterwards.[10]

Establishing a timeline of his work is now impossible, since no document provides chronological references. Themistius, a 4th-century Byzantine rhetorician, mentions that he was the "first of the known Greeks to publish a written document on nature." Therefore, his texts would be amongst the earliest written in prose, at least in the Western world. By the time of Plato, his philosophy was almost forgotten, and Aristotle, his successor Theophrastus and a few doxographers provide us with the little information that remains. However, we know from Aristotle that Thales, also from Miletus, precedes Anaximander. It is debatable whether Thales actually was the teacher of Anaximander, but there is no doubt that Anaximander was influenced by Thales' theory that everything is derived from water. One thing that is not debatable is that even the ancient Greeks considered Anaximander to be from the Monist school which began in Miletus, with Thales followed by Anaximander and which ended with Anaximenes.[11] 3rd-century Roman rhetorician Aelian depicts Anaximander as leader of the Milesian colony to Apollonia on the Black Sea coast, and hence some have inferred that he was a prominent citizen.[12] Indeed, Various History (III, 17) explains that philosophers sometimes also dealt with political matters. It is very likely that leaders of Miletus sent him there as a legislator to create a constitution or simply to maintain the colony's allegiance.

Anaximander lived the final few years of his life as a subject of the Persian Achaemenid Empire.[13]

Theories

Anaximander's theories were influenced by the Greek mythical tradition, and by some ideas of Thales – the father of philosophy – as well as by observations made by older civilizations in the Near East, especially Babylon.[14][15] All these were developed rationally. In his desire to find some universal principle, he assumed, like traditional religion, the existence of a cosmic order; and his ideas on this used the old language of myths which ascribed divine control to various spheres of reality. This was a common practice for the Greek philosophers in a society which saw gods everywhere, and therefore could fit their ideas into a tolerably elastic system.[16]

Some scholars see a gap between the existing mythical and the new rational way of thought which is the main characteristic of the archaic period (8th to 6th century BC) in the Greek city-states.[17] This has given rise to the phrase "Greek miracle". But if we follow carefully the course of Anaximander's ideas, we will notice that there was not such an abrupt break as initially appears. The basic elements of nature (water, air, fire, earth) which the first Greek philosophers believed made up the universe in fact represent the primordial forces imagined in earlier ways of thinking. Their collision produced what the mythical tradition had called cosmic harmony. In the old cosmogonies – Hesiod (8th – 7th century BC) and Pherecydes (6th century BC) – Zeus establishes his order in the world by destroying the powers which were threatening this harmony (the Titans). Anaximander claimed that the cosmic order is not monarchic but geometric, and that this causes the equilibrium of the earth, which is lying in the centre of the universe. This is the projection on nature of a new political order and a new space organized around a centre which is the static point of the system in the society as in nature.[18] In this space there is isonomy (equal rights) and all the forces are symmetrical and transferable. The decisions are now taken by the assembly of demos in the agora which is lying in the middle of the city.[19]

The same rational way of thought led him to introduce the abstract apeiron (indefinite, infinite, boundless, unlimited[20]) as an origin of the universe, a concept that is probably influenced by the original Chaos (gaping void, abyss, formless state) of the mythical Greek cosmogony from which everything else appeared.[21] It also takes notice of the mutual changes between the four elements. Origin, then, must be something else unlimited in its source, that could create without experiencing decay, so that genesis would never stop.[22]

Apeiron

The Refutation attributed to Hippolytus of Rome (I, 5), and the later 6th century Byzantine philosopher Simplicius of Cilicia, attribute to Anaximander the earliest use of the word apeiron (ἄπειρον "infinite" or "limitless") to designate the original principle. He was the first philosopher to employ, in a philosophical context, the term archē (ἀρχή), which until then had meant beginning or origin.

"That Anaximander called this something by the name of Φύσις is the natural interpretation of what Theophrastos says; the current statement that the term ἀρχή was introduced by him appears to be due to a misunderstanding."[23]

And "Hippolytos, however, is not an independent authority, and the only question is what Theophrastos wrote."[24]

For him, it became no longer a mere point in time, but a source that could perpetually give birth to whatever will be. The indefiniteness is spatial in early usages as in Homer (indefinite sea) and as in Xenophanes (6th century BC) who said that the earth went down indefinitely (to apeiron) i.e. beyond the imagination or concept of men.[25]

Burnet (1930) in Early Greek Philosophy says:

"Nearly all we know of Anaximander’s system is derived in the last resort from Theophrastos, who certainly knew his book. He seems once at least to have quoted Anaximander's own words, and he criticised his style. Here are the remains of what he said of him in the First Book:

"Anaximander of Miletos, son of Praxiades, a fellow-citizen and associate of Thales, said that the material cause and first element of things was the Infinite, he being the first to introduce this name of the material cause. He says it is neither water nor any other of the so-called elements, but a substance different from them which is infinite" [apeiron, or ἄπειρον] "from which arise all the heavens and the worlds within them.—Phys, Op. fr. 2 (Dox. p. 476 ; R. P. 16)."[26]

Burnet's quote from the "First Book" is his translation of Theophrastos' Physic Opinion fragment 2 as it appears in p. 476 of Historia Philosophiae Graecae (1898) by Ritter and Preller and section 16 of Doxographi Graeci (1879) by Diels.

By ascribing the "Infinite" with a "material cause", Theophrastos is following the Aristotelian tradition of "nearly always discussing the facts from the point of view of his own system".[27]

Aristotle writes (Metaphysics, I.III 3–4) that the Pre-Socratics were searching for the element that constitutes all things. While each pre-Socratic philosopher gave a different answer as to the identity of this element (water for Thales and air for Anaximenes), Anaximander understood the beginning or first principle to be an endless, unlimited primordial mass (apeiron), subject to neither old age nor decay, that perpetually yielded fresh materials from which everything we perceive is derived.[28] He proposed the theory of the apeiron in direct response to the earlier theory of his teacher, Thales, who had claimed that the primary substance was water. The notion of temporal infinity was familiar to the Greek mind from remote antiquity in the religious concept of immortality, and Anaximander's description was in terms appropriate to this conception. This archē is called "eternal and ageless". (Hippolytus (?), Refutation, I,6,I;DK B2)[29]

"Aristotle puts things in his own way regardless of historical considerations, and it is difficult to see that it is more of an anachronism to call the Boundless “ intermediate between the elements ” than to say that it is " distinct from the elements.” Indeed, if once we introduce the elements at all, the former description is the more adequate of the two. At any rate, if we refuse to understand these passages as referring to Anaximander, we shall have to say that Aristotle paid a great deal of attention to some one whose very name has been lost, and who not only agreed with some of Anaximander’s views, but also used some of his most characteristic expressions. We may add that in one or two places Aristotle certainly seems to identify the “ intermediate ” with the something “ distinct from ” the elements."[30]

"It is certain that he [Anaximander] cannot have said anything about elements, which no one thought of before Empedokles, and no one could think of before Parmenides. The question has only been mentioned because it has given rise to a lengthy controversy, and because it throws light on the historical value of Aristotle’s statements. From the point of view of his own system, these may be justified; but we shall have to remember in other cases that, when he seems to attribute an idea to some earlier thinker, we are not bound to take what he says in an historical sense."[31]

For Anaximander, the principle of things, the constituent of all substances, is nothing determined and not an element such as water in Thales' view. Neither is it something halfway between air and water, or between air and fire, thicker than air and fire, or more subtle than water and earth.[32] Anaximander argues that water cannot embrace all of the opposites found in nature — for example, water can only be wet, never dry — and therefore cannot be the one primary substance; nor could any of the other candidates. He postulated the apeiron as a substance that, although not directly perceptible to us, could explain the opposites he saw around him.

"If Thales had been right in saying that water was the fundamental reality, it would not be easy to see how anything else could ever have existed. One side of the opposition, the cold and moist, would have had its way unchecked, and the warm and dry would have been driven from the field long ago. We must, then, have something not itself one of the warring opposites, something more primitive, out of which they arise, and into which they once more pass away."[23]

Anaximander explains how the four elements of ancient physics (air, earth, water and fire) are formed, and how Earth and terrestrial beings are formed through their interactions. Unlike other Pre-Socratics, he never defines this principle precisely, and it has generally been understood (e.g., by Aristotle and by Saint Augustine) as a sort of primal chaos. According to him, the Universe originates in the separation of opposites in the primordial matter. It embraces the opposites of hot and cold, wet and dry, and directs the movement of things; an entire host of shapes and differences then grow that are found in "all the worlds" (for he believed there were many).[12]

"Anaximander taught, then, that there was an eternal. The indestructible something out of which everything arises, and into which everything returns; a boundless stock from which the waste of existence is continually made good, “elements.”. That is only the natural development of the thought we have ascribed to Thales, and there can be no doubt that Anaximander at least formulated it distinctly. Indeed, we can still follow to some extent the reasoning which led him to do so. Thales had regarded water as the most likely thing to be that of which all others are forms; Anaximander appears to have asked how the primary substance could be one of these particular things. His argument seems to be preserved by Aristotle, who has the following passage in his discussion of the Infinite: "Further, there cannot be a single, simple body which is infinite, either, as some hold, one distinct from the elements, which they then derive from it, or without this qualification. For there are some who make this. (i.e. a body distinct from the elements). the infinite, and not air or water, in order that the other things may not be destroyed by their infinity. They are in opposition one to another. air is cold, water moist, and fire hot. and therefore, if any one of them were infinite, the rest would have ceased to be by this time. Accordingly they say that what is infinite is something other than the elements, and from it the elements arise.'—Aristotle Physics. F, 5 204 b 22 (Ritter and Preller (1898) Historia Philosophiae Graecae, section 16 b)."[33]

Anaximander maintains that all dying things are returning to the element from which they came (apeiron). The one surviving fragment of Anaximander's writing deals with this matter. Simplicius transmitted it as a quotation, which describes the balanced and mutual changes of the elements:[34][35]

Whence things have their origin,

Thence also their destruction happens,

According to necessity;

For they give to each other justice and recompense

For their injustice

In conformity with the ordinance of Time.

Simplicius mentions that Anaximander said all these "in poetic terms", meaning that he used the old mythical language. The goddess Justice (Dike) keeps the cosmic order. This concept of returning to the element of origin was often revisited afterwards, notably by Aristotle,[36] and by the Greek tragedian Euripides: "what comes from earth must return to earth."[37] Friedrich Nietzsche, in his Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, stated that Anaximander viewed "... all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance."[38] Physicist Max Born, in commenting upon Werner Heisenberg's arriving at the idea that the elementary particles of quantum mechanics are to be seen as different manifestations, different quantum states, of one and the same “primordial substance,”' proposed that this primordial substance be called apeiron.[39]

Cosmology

Anaximander's bold use of non-mythological explanatory hypotheses considerably distinguishes him from previous cosmology writers such as Hesiod. It confirms that pre-Socratic philosophers were making an early effort to demystify physical processes. His major contribution to history was writing the oldest prose document about the Universe and the origins of life; for this he is often called the "Father of Cosmology" and founder of astronomy. However, pseudo-Plutarch states that he still viewed celestial bodies as deities.[40]

Anaximander was the first to conceive a mechanical model of the world. In his model, the Earth floats very still in the centre of the infinite, not supported by anything. It remains "in the same place because of its indifference", a point of view that Aristotle considered ingenious, but false, in On the Heavens.[41] Its curious shape is that of a cylinder[42] with a height one-third of its diameter. The flat top forms the inhabited world, which is surrounded by a circular oceanic mass.

Anaximander's realization that the Earth floats free without falling and does not need to be resting on something has been indicated by many as the first cosmological revolution and the starting point of scientific thinking.[43][44] Karl Popper calls this idea "one of the boldest, most revolutionary, and most portentous ideas in the whole history of human thinking."[45] Such a model allowed the concept that celestial bodies could pass under the Earth, opening the way to Greek astronomy.

At the origin, after the separation of hot and cold, a ball of flame appeared that surrounded Earth like bark on a tree. This ball broke apart to form the rest of the Universe. It resembled a system of hollow concentric wheels, filled with fire, with the rims pierced by holes like those of a flute. Consequently, the Sun was the fire that one could see through a hole the same size as the Earth on the farthest wheel, and an eclipse corresponded with the occlusion of that hole. The diameter of the solar wheel was twenty-seven times that of the Earth (or twenty-eight, depending on the sources)[46] and the lunar wheel, whose fire was less intense, eighteen (or nineteen) times. Its hole could change shape, thus explaining lunar phases. The stars and the planets, located closer,[47] followed the same model.[48]

Anaximander was the first astronomer to consider the Sun as a huge mass, and consequently, to realize how far from Earth it might be, and the first to present a system where the celestial bodies turned at different distances. Furthermore, according to Diogenes Laertius (II, 2), he built a celestial sphere. This invention undoubtedly made him the first to realize the obliquity of the Zodiac as the Roman philosopher Pliny the Elder reports in Natural History (II, 8). It is a little early to use the term ecliptic, but his knowledge and work on astronomy confirm that he must have observed the inclination of the celestial sphere in relation to the plane of the Earth to explain the seasons. The doxographer and theologian Aetius attributes to Pythagoras the exact measurement of the obliquity.

Multiple worlds

According to Simplicius, Anaximander already speculated on the plurality of worlds, similar to atomists Leucippus and Democritus, and later philosopher Epicurus. These thinkers supposed that worlds appeared and disappeared for a while, and that some were born when others perished. They claimed that this movement was eternal, "for without movement, there can be no generation, no destruction".[49]

In addition to Simplicius, Hippolytus[50] reports Anaximander's claim that from the infinite comes the principle of beings, which themselves come from the heavens and the worlds (several doxographers use the plural when this philosopher is referring to the worlds within,[51] which are often infinite in quantity). Cicero writes that he attributes different gods to the countless worlds.[52]

This theory places Anaximander close to the Atomists and the Epicureans who, more than a century later, also claimed that an infinity of worlds appeared and disappeared. In the timeline of the Greek history of thought, some thinkers conceptualized a single world (Plato, Aristotle, Anaxagoras and Archelaus), while others instead speculated on the existence of a series of worlds, continuous or non-continuous (Anaximenes, Heraclitus, Empedocles and Diogenes).

Meteorological phenomena

Anaximander attributed some phenomena, such as thunder and lightning, to the intervention of elements, rather than to divine causes.[53] In his system, thunder results from the shock of clouds hitting each other; the loudness of the sound is proportionate with that of the shock. Thunder without lightning is the result of the wind being too weak to emit any flame, but strong enough to produce a sound. A flash of lightning without thunder is a jolt of the air that disperses and falls, allowing a less active fire to break free. Thunderbolts are the result of a thicker and more violent air flow.[54]

He saw the sea as a remnant of the mass of humidity that once surrounded Earth.[55] A part of that mass evaporated under the sun's action, thus causing the winds and even the rotation of the celestial bodies, which he believed were attracted to places where water is more abundant.[56] He explained rain as a product of the humidity pumped up from Earth by the sun.[9] For him, the Earth was slowly drying up and water only remained in the deepest regions, which someday would go dry as well. According to Aristotle's Meteorology (II, 3), Democritus also shared this opinion.

Origin of humankind

Anaximander speculated about the beginnings and origin of animal life, and that humans came from other animals in waters.[15][57] He claimed that animals sprang out of the sea long ago, born trapped in a spiny bark, but as they got older, the bark would dry up and animals would be able to break it.[58] As the early humidity evaporated, dry land emerged and, in time, humankind had to adapt.[dubious ] The 3rd century Roman writer Censorinus reports:

Anaximander of Miletus considered that from warmed up water and earth emerged either fish or entirely fishlike animals. Inside these animals, men took form and embryos were held prisoners until puberty; only then, after these animals burst open, could men and women come out, now able to feed themselves.[59]

Anaximander put forward the idea that humans had to spend part of this transition inside the mouths of big fish to protect themselves from the Earth's climate until they could come out in open air and lose their scales.[60] He thought that, considering humans' extended infancy, we could not have survived in the primeval world in the same manner we do presently.

Other accomplishments

Cartography

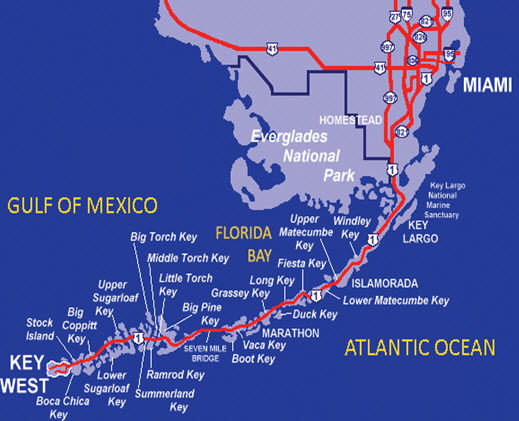

Both Strabo and Agathemerus (later Greek geographers) claim that, according to the geographer Eratosthenes, Anaximander was the first to publish a map of the world. The map probably inspired the Greek historian Hecataeus of Miletus to draw a more accurate version. Strabo viewed both as the first geographers after Homer.

Maps were produced in ancient times, also notably in Egypt, Lydia, the Middle East, and Babylon. Only some small examples survived until today. The unique example of a world map comes from late Babylonian tablet BM 92687 later than 9th century BC but is based probably on a much older map. These maps indicated directions, roads, towns, borders, and geological features. Anaximander's innovation was to represent the entire inhabited land known to the ancient Greeks.

Such an accomplishment is more significant than it at first appears. Anaximander most likely drew this map for three reasons.[62] First, it could be used to improve navigation and trade between Miletus's colonies and other colonies around the Mediterranean Sea and Black Sea. Second, Thales would probably have found it easier to convince the Ionian city-states to join in a federation in order to push the Median threat away if he possessed such a tool. Finally, the philosophical idea of a global representation of the world simply for the sake of knowledge was reason enough to design one.

Surely aware of the sea's convexity, he may have designed his map on a slightly rounded metal surface. The centre or “navel” of the world (ὀμφαλός γῆς omphalós gẽs) could have been Delphi, but is more likely in Anaximander's time to have been located near Miletus. The Aegean Sea was near the map's centre and enclosed by three continents, themselves located in the middle of the ocean and isolated like islands by sea and rivers. Europe was bordered on the south by the Mediterranean Sea and was separated from Asia by the Black Sea, the Lake Maeotis, and, further east, either by the Phasis River (now called the Rioni) or the Tanais. The Nile flowed south into the ocean, separating Libya (which was the name for the part of the then-known African continent) from Asia.

Gnomon

The Suda relates that Anaximander explained some basic notions of geometry. It also mentions his interest in the measurement of time and associates him with the introduction in Greece of the gnomon. In Lacedaemon, he participated in the construction, or at least in the adjustment, of sundials to indicate solstices and equinoxes.[63] Indeed, a gnomon required adjustments from a place to another because of the difference in latitude.

In his time, the gnomon was simply a vertical pillar or rod mounted on a horizontal plane. The position of its shadow on the plane indicated the time of day. As it moves through its apparent course, the Sun draws a curve with the tip of the projected shadow, which is shortest at noon, when pointing due south. The variation in the tip's position at noon indicates the solar time and the seasons; the shadow is longest on the winter solstice and shortest on the summer solstice.

The invention of the gnomon itself cannot be attributed to Anaximander because its use, as well as the division of days into twelve parts, came from the Babylonians. It is they, according to Herodotus' Histories (II, 109), who gave the Greeks the art of time measurement. It is likely that he was not the first to determine the solstices, because no calculation is necessary. On the other hand, equinoxes do not correspond to the middle point between the positions during solstices, as the Babylonians thought. As the Suda seems to suggest, it is very likely that with his knowledge of geometry, he became the first Greek to accurately determine the equinoxes.

Prediction of an earthquake

In his philosophical work De Divinatione (I, 50, 112), Cicero states that Anaximander convinced the inhabitants of Lacedaemon to abandon their city and spend the night in the country with their weapons because an earthquake was near.[64] The city collapsed when the top of the Taygetus split like the stern of a ship. Pliny the Elder also mentions this anecdote (II, 81), suggesting that it came from an "admirable inspiration", as opposed to Cicero, who did not associate the prediction with divination.

Interpretations

Bertrand Russell in the History of Western Philosophy interprets Anaximander's theories as an assertion of the necessity of an appropriate balance between earth, fire, and water, all of which may be independently seeking to aggrandize their proportions relative to the others. Anaximander seems to express his belief that a natural order ensures balance between these elements, that where there was fire, ashes (earth) now exist.[65] His Greek peers echoed this sentiment with their belief in natural boundaries beyond which not even the gods could operate.

Friedrich Nietzsche, in Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks, claimed that Anaximander was a pessimist who asserted that the primal being of the world was a state of indefiniteness. In accordance with this, anything definite has to eventually pass back into indefiniteness. In other words, Anaximander viewed "...all coming-to-be as though it were an illegitimate emancipation from eternal being, a wrong for which destruction is the only penance". (Ibid., § 4) The world of individual objects, in this way of thinking, has no worth and should perish.[66]

Martin Heidegger lectured extensively on Anaximander, and delivered a lecture entitled "Anaximander's Saying" which was subsequently included in Off the Beaten Track. The lecture examines the ontological difference and the oblivion of Being or Dasein in the context of the Anaximander fragment.[67] Heidegger's lecture is, in turn, an important influence on the French philosopher Jacques Derrida.[68]

Works

According to the Suda:[69]

- On Nature (Περὶ φύσεως / Perì phúseôs)

- Rotation of the Earth (Γῆς περίοδος / Gễs períodos)

- On Fixed stars (Περὶ τῶν ἀπλανῶν / Perì tỗn aplanỗn)

- The [Celestial] Sphere (Σφαῖρα / Sphaĩra)

See also

Footnotes

- Themistius and Simplicius also mention some work "on nature". The list could refer to book titles or simply their topics. Again, no one can tell because there is no punctuation sign in Ancient Greek. Furthermore, this list is incomplete since the Suda ends it with ἄλλα τινά, thus implying "other works".

References

Primary sources

- Aelian: Various History (III, 17)

- Aëtius: De Fide (I-III; V)

- Agathemerus: A Sketch of Geography in Epitome (I, 1)

- Aristotle: Meteorology (II, 3) Translated by E. W. Webster

- Aristotle: On Generation and Corruption (II, 5) Translated by H. H. Joachim

- Aristotle: On the Heavens (II, 13) Translated by J. L. Stocks

- Aristotle. – via Wikisource. (III, 5, 204 b 33–34)

- Censorinus: De Die Natali (IV, 7) See original text at LacusCurtius

- Cicero (1853) [original: 44 BC]. . Translated by Charles Duke Yonge – via Wikisource. (I, 50, 112)

- Cicero: On the Nature of the Gods (I, 10, 25)

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.

Laërtius, Diogenes (1925). . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. 1:2. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library.- Euripides: The Suppliants (532) Translated by E. P. Coleridge

- Eusebius of Caesarea: Preparation for the Gospel (X, 14, 11) Translated by E.H. Gifford

- Heidel, W.A. Anaximander's Book: PAAAS, vol. 56, n.7, 1921, pp. 239–288.

- Herodotus: Histories (II, 109) See original text in Perseus project

- Hippolytus (?): Refutation of All Heresies (I, 5) Translated by Roberts and Donaldson

- Pliny the Elder: Natural History (II, 8) See original text in Perseus project

- Pseudo-Plutarch: The Doctrines of the Philosophers (I, 3; I, 7; II, 20–28; III, 2–16; V, 19)

- Seneca the Younger: Natural Questions (II, 18)

- Simplicius: Comments on Aristotle's Physics (24, 13–25; 1121, 5–9)

- Strabo: Geography (I, 1) Books 1‑7, 15‑17 translated by H. L. Jones

- Themistius: Oratio (36, 317)

- The Suda (Suda On Line)

Secondary sources

- Brumbaugh, Robert S. (1964). The Philosopher's of Greece. New York: Thomas Y. Crowell.

- Burnet, John (1920). Early Greek Philosophy (3rd ed.). London: Black. Archived from the original on 2011-01-11. Retrieved 2011-02-24.

- Conche, Marcel (1991). Anaximandre: Fragments et témoignages (in French). Paris: Presses universitaires de France. ISBN 2-13-043785-0. The default source; anything not otherwise attributed should be in Conche.

- Couprie, Dirk L.; Robert Hahn; Gerard Naddaf (2003). Anaximander in Context: New Studies in the Origins of Greek Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-5538-6.

- Furley, David J.; Reginald E. Allen (1970). Studies in Presocratic Philosophy. 1. London: Routledge. OCLC 79496039.

- Guthrie, W.K.C. (1962). The Earlier Presocratics and the Pythagoreans. A History of Greek Philosophy. 1. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hahn, Robert (2001). Anaximander and the Architects. The Contribution of Egyptian and Greek Architectural Technologies to the Origins of Greek Philosophy. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0791447949.

- Heidegger, Martin (2002). Off the Beaten Track. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-80114-1.

- Kahn, Charles H. (1960). Anaximander and the Origins of Greek Cosmology. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Kirk, Geoffrey S.; Raven, John E. (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Luchte, James (2011). Early Greek Thought: Before the Dawn. London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 978-0567353313.

- Nietzsche, Friedrich (1962). Philosophy in the Tragic Age of the Greeks. Chicago: Regnery. ISBN 0-89526-944-9.

- Robinson, John Mansley (1968). An Introduction to Early Greek Philosophy. Houghton and Mifflin. ISBN 0-395-05316-1.

- Ross, Stephen David (1993). Injustice and Restitution: The Ordinance of Time. Albany: State University of New York Press. ISBN 0-7914-1670-4.

- Rovelli, Carlo (2011). The First Scientist, Anaximander and his Legacy. Yardley: Westholme. ISBN 978-1-59416-131-5.

- Sandywell, Barry (1996). Presocratic Reflexivity: The Construction of Philosophical Discourse, c. 600–450 BC. 3. London: Routledge.

- Seligman, Paul (1962). The "Apeiron" of Anaximander. London: Athlone Press.

- Vernant, Jean-Pierre (1982). The Origins of Greek Thought. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 0-8014-9293-9.

- Wheelwright, Philip, ed. (1966). The Presocratics. New York: Macmillan.

- Wright, M.R. (1995). Cosmology in Antiquity. London: Routledge.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anaximander. |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Anaximander |

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Anaximander

Greek Wikisource has original text related to this article: Anaximander- O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Anaximander", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews.

- Philoctete – Anaximandre: Fragments ((Grk icon)) (in French and English)

- The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy – Anaximander

- Extensive bibliography by Dirk Couprie

- Weisstein, Eric Wolfgang (ed.). "Anaximander of Miletus (610-ca. 546 BC)". ScienceWorld.

- Anaximander entry by John Burnet contains fragments of Anaximander

- Anaximander of Miletus Life and Work - Fragments and Testimonies by Giannis Stamatellos

- 6th-century BC Greek people

- 6th-century BC philosophers

- 610s BC births

- 540s BC deaths

- Ancient Greek astronomers

- Ancient Greek cartographers

- Ancient Greek metaphysicians

- Ancient Greek physicists

- Ancient Greeks from the Achaemenid Empire

- Ancient Milesians

- Natural philosophers

- Philosophers of ancient Ionia

- Presocratic philosophers

Languages

During the period of Achaemenid rule in Miletus, which was the most important city of Ionia, there lived the eminent philosopher Anaximander and the geographer and historian Hecataeus.

- "Ἀναξίμανδρος [...] λέγει δ' αὐτὴν μήτε ὕδωρ μήτε ἄλλο τι τῶν καλουμένων εἶναι στοιχείων, ἀλλ' ἑτέραν τινὰ φύσιν ἄπειρον, ἐξ ἧς ἅπαντας γίνεσθαι τοὺς οὐρανοὺς καὶ τοὺς ἐν αὐτοῖς κόσμους· ἐξ ὧν δὲ ἡ γένεσίς ἐστι τοῖς οὖσι, καὶ τὴν φθορὰν εἰς ταῦτα γίνεσθαι κατὰ τὸ χρεών· διδόναι γὰρ αὐτὰ δίκην καὶ τίσιν ἀλλήλοις τῆς ἀδικίας κατὰ τὴν τοῦ χρόνου τάξιν, ποιητικωτέροις οὕτως ὀνόμασιν αὐτὰ λέγων. δῆλον δὲ ὅτι τὴν εἰς ἄλληλα μεταβολὴν τῶν τεττάρων στοιχείων οὗτος θεασάμενος οὐκ ἠξίωσεν ἕν τι τούτων ὑποκείμενον ποιῆσαι, ἀλλά τι ἄλλο παρὰ ταῦτα· οὗτος δὲ οὐκ ἀλλοιουμένου τοῦ στοιχείου τὴν γένεσιν ποιεῖ, ἀλλ' ἀποκρινομένων τῶν ἐναντίων διὰ τῆς αἰδίου κινήσεως."

- "[The Sun] is a circle twenty-eight times as big as the Earth, with the outline similar to that of a fire-filled chariot wheel, on which appears a mouth in certain places and through which it exposes its fire, as through the hole on a flute. [...] the Sun is equal to the Earth, but the circle on which it breathes and on which it's borne is twenty-seven times as big as the whole earth. [...] [The eclipse] is when the mouth from which comes the fire heat is closed. [...] [The Moon] is a circle nineteen times as big as the whole earth, all filled with fire, like that of the Sun".

- "Anaximandri autem opinio est nativos esse deos longis intervallis orientis occidentisque, eosque innumerabiles esse mundos."

- "For Anaximander, gods were born, but the time is long between their birth and their death; and the worlds are countless."

- "Anaximander claims that all this is done by the wind, for when it happens to be enclosed in a thick cloud, then by its subtlety and lightness, the rupture produces the sound; and the scattering, because of the darkness of the cloud, creates the light."

Colossus of Rhodes

The Colossus of Rhodes (Ancient Greek: ὁ Κολοσσὸς Ῥόδιος, romanized: ho Kolossòs Rhódios Greek: Κολοσσός της Ρόδου, romanized: Kolossós tes Rhódou)[a] was a statue of the Greek sun-god Helios, erected in the city of Rhodes, on the Greek island of the same name, by Chares of Lindos in 280 BC. One of the Seven Wonders of the Ancient World, it was constructed to celebrate Rhodes' victory over the ruler of Cyprus, Antigonus I Monophthalmus, whose son Demetrius I of Macedon unsuccessfully besieged Rhodes in 305 BC. According to most contemporary descriptions, the Colossus stood approximately 70 cubits, or 33 metres (108 feet) high—the approximate height of the modern Statue of Liberty from feet to crown—making it the tallest statue of the ancient world.[2] It collapsed during the earthquake of 226 BC, although parts of it were preserved. In accordance with a certain oracle, the Rhodians did not build it again.[3] John Malalas wrote that Hadrian in his reign reerected the Colossus,[4] but he was wrong.[5] According to Suda the Rhodians were called Colossaeans (Κολοσσαεῖς), because they erected on the island the statue.[6]

Since 2008, a series of as-yet-unrealized proposals to build a new Colossus at Rhodes Harbour have been announced, although the actual location of the original monument remains in dispute.[7][8]

Siege of Rhodes

In the late 4th century BC, Rhodes, allied with Ptolemy I of Egypt, prevented a mass invasion staged by their common enemy, Antigonus I Monophthalmus.

In 304 BC a relief force of ships sent by Ptolemy arrived, and Demetrius (son of Antigonus) and his army abandoned the siege, leaving behind most of their siege equipment. To celebrate their victory, the Rhodians sold the equipment left behind for 300 talents[9] and decided to use the money to build a colossal statue of their patron god, Helios. Construction was left to the direction of Chares, a native of Lindos in Rhodes, who had been involved with large-scale statues before. His teacher, the sculptor Lysippos, had constructed a 22-metre-high (72-foot)[10] bronze statue of Zeus at Tarentum.

Construction

Construction began in 292 BC. Ancient accounts, which differ to some degree, describe the structure as being built with iron tie bars to which brass plates were fixed to form the skin. The interior of the structure, which stood on a 15-metre-high (49-foot) white marble pedestal near the Mandraki harbour entrance, was then filled with stone blocks as construction progressed.[11] Other sources place the Colossus on a breakwater in the harbour. According to most contemporary descriptions, the statue itself was about 70 cubits, or 32 metres (105 feet) tall.[12] Much of the iron and bronze was reforged from the various weapons Demetrius's army left behind, and the abandoned second siege tower may have been used for scaffolding around the lower levels during construction. Upper portions were built with the use of a large earthen ramp. During the building, workers would pile mounds of earth on the sides of the colossus. Upon completion all of the earth was removed and the colossus was left to stand alone. After twelve years, in 280 BC, the statue was completed. Preserved in Greek anthologies of poetry is what is believed to be the genuine dedication text for the Colossus.[13]

To you, O Sun, the people of Dorian Rhodes set up this bronze statue reaching to Olympus, when they had pacified the waves of war and crowned their city with the spoils taken from the enemy. Not only over the seas but also on land did they kindle the lovely torch of freedom and independence. For to the descendants of Herakles belongs dominion over sea and land.

Modern engineers have put forward a plausible hypothesis for the statue's construction, based on the technology of the time (which was not based on the modern principles of earthquake engineering), and the accounts of Philo and Pliny, who saw and described the ruins.[14]

The base pedestal was said to be at least 18 metres (59 feet) in diameter, and either circular or octagonal. The feet were carved in stone and covered with thin bronze plates riveted together. Eight forged iron bars set in a radiating horizontal position formed the ankles and turned up to follow the lines of the legs while becoming progressively smaller. Individually cast curved bronze plates 60 inches (1,500 mm) square with turned-in edges were joined together by rivets through holes formed during casting to form a series of rings. The lower plates were one inch (25 mm) in thickness to the knee and 3⁄4-inch (20 mm) thick from knee to abdomen, while the upper plates were 1⁄4–1⁄2-inch (6.5–12.5 mm) thick except where additional strength was required at joints such as the shoulder, neck, etc.

Destruction

The statue stood for 54 years until Rhodes was hit by the 226 BC earthquake, when significant damage was also done to large portions of the city, including the harbour and commercial buildings, which were destroyed.[15] The statue snapped at the knees and fell over onto the land. Ptolemy III offered to pay for the reconstruction of the statue, but the oracle of Delphi made the Rhodians afraid that they had offended Helios, and they declined to rebuild it.

The remains lay on the ground as described by Strabo (xiv.2.5) for over 800 years, and even broken, they were so impressive that many travelled to see them. Pliny the Elder remarked that few people could wrap their arms around the fallen thumb and that each of its fingers was larger than most statues.[16]

In 653, an Arab force under Muslim caliph Muawiyah I captured Rhodes, and according to The Chronicle of Theophanes the Confessor,[17] the statue was melted down and sold to a Jewish merchant of Edessa who loaded the bronze on 900 camels.[18] The Arab destruction and the purported sale to a Jew possibly originated as a powerful metaphor for Nebuchadnezzar's dream of the destruction of a great statue.[19]

The same story is recorded by Bar Hebraeus, writing in Syriac in the 13th century in Edessa:[20] (after the Arab pillage of Rhodes) "And a great number of men hauled on strong ropes which were tied round the brass Colossus which was in the city and pulled it down. And they weighed from it three thousand loads of Corinthian brass, and they sold it to a certain Jew from Emesa" (the Syrian city of Homs). Theophanes is the sole source of this account and all other sources can be traced to him.[citation needed]

Posture

The harbour-straddling Colossus was a figment of medieval imaginations based on the dedication text's mention of "over land and sea" twice and the writings of an Italian visitor who in 1395 noted that local tradition held that the right foot had stood where the church of St John of the Colossus was then located.[21] Many later illustrations show the statue with one foot on either side of the harbour mouth with ships passing under it. References to this conception are also found in literary works. Shakespeare's Cassius in Julius Caesar (I, ii, 136–38) says of Caesar:

Why man, he doth bestride the narrow world

Like a Colossus, and we petty men

Walk under his huge legs and peep about

To find ourselves dishonourable graves

Shakespeare alludes to the Colossus also in Troilus and Cressida (V.5) and in Henry IV, Part 1 (V.1).

"The New Colossus" (1883), a sonnet by Emma Lazarus written on a cast bronze plaque and mounted inside the pedestal of the Statue of Liberty in 1903, contrasts the latter with:

The brazen giant of Greek fame

with conquering limbs astride from land to land

While these fanciful images feed the misconception, the mechanics of the situation reveal that the Colossus could not have straddled the harbour as described in Lemprière's Classical Dictionary. If the completed statue had straddled the harbour, the entire mouth of the harbour would have been effectively closed during the entirety of the construction, and the ancient Rhodians did not have the means to dredge and re-open the harbour after construction. Also, the fallen statue would have blocked the harbour, and since the ancient Rhodians did not have the ability to remove the fallen statue from the harbour, it would not have remained visible on land for the next 800 years, as discussed above. Even neglecting these objections, the statue was made of bronze, and engineering analyses indicate that it could not have been built with its legs apart without collapsing under its own weight.[21] Many researchers have considered alternative positions for the statue which would have made it more feasible for actual construction by the ancients.[21][22] There is also no evidence that the statue held a torch aloft; the records simply say that after completion, the Rhodians kindled the "torch of freedom". A relief in a nearby temple shows Helios standing with one hand shielding his eyes, similar to the way a person shields their eyes when looking toward the sun, and it is quite possible that the colossus was constructed in the same pose. While scholars do not know what the statue looked like, they do have a good idea of what the head and face looked like, as it was of a standard rendering at the time. The head would have had curly hair with evenly spaced spikes of bronze or silver flame radiating, similar to the images found on contemporary Rhodian coins.[21]

Possible locations

While scholars generally agree that anecdotal depictions of the Colossus straddling the harbour's entry point have no historic or scientific basis,[21] the monument's actual location remains a matter of debate.

The floor of the Fortress of St Nicholas, near the harbour entrance, contains a circle of sandstone blocks of unknown origin or purpose. Curved blocks of marble that were incorporated into the Fortress structure, but are considered too intricately cut to have been quarried for that purpose, have been posited as the remnants of a marble base for the Colossus, which would have stood on the sandstone block foundation.[21]

Archaeologist Ursula Vedder postulates that the Colossus was not located in the harbour area at all, but rather was part of the Acropolis of Rhodes, which stood on a hill that overlooks the port area. The ruins of a large temple, traditionally thought to have been dedicated to Apollo, are situated at the highest point of the hill. Vedder believes that the structure would actually have been a Helios sanctuary, and a portion of its enormous stone foundation could have served as the supporting platform for the Colossus.[23]

Modern Colossus projects

In 2008, The Guardian reported that a modern Colossus was to be built at the harbour entrance by German artist Gert Hof leading a Cologne-based team. It was to be a giant light sculpture made partially out of melted-down weapons from around the world. It would cost up to €200 million.[24]

In December 2015, a group of European architects announced plans to build a modern Colossus bestriding two piers at the harbour entrance, despite a preponderance of evidence and scholarly opinion that the original monument could not have stood there.[7][8] The new statue, 150 metres (490 ft) tall (five times the height of the original) would cost an estimated US$283 million, funded by private donations and crowdsourcing.[8] The statue would include a cultural centre, a library, an exhibition hall, and a lighthouse, all powered by solar panels.[8] As of October 2018, no such plans have been carried out and the website for the project is offline.

See also

- Twelve Metal Colossi

- The Colossus of Rhodes (Dalí)

- The Colossus of Rhodes (film)

- The New Colossus

- The Rhodes Colossus

- List of statues by height

References

Notes

- Kolossos means "giant statue". R. S. P. Beekes has suggested a Pre-Greek proto-form *koloky-.[1]

References

- Smith, Helena (2008-11-17). "Colossus of Rhodes to be rebuilt as giant light sculpture". The Guardian. Retrieved 2017-12-07.

Sources

- Ashley, James R. (2004). The Macedonian Empire: The Era of Warfare Under Philip II and Alexander the Great, 359-323 B.C. McFarland & Company. p. 75. ISBN 0-7864-1918-0.

- Gabriel, Albert. Bulletin de Correspondance Hellenique 56 (1932), pp. 331–59.

- Haynes, D.E.L. "Philo of Byzantium and the Colossus of Rhodes" The Journal of Hellenic Studies 77.2 (1957), pp. 311–312. A response to Maryon.

- Maryon, Herbert, "The Colossus of Rhodes" in The Journal of Hellenic Studies 76 (1956), pp. 68–86. A sculptor's speculations on the Colossus of Rhodes.

Further reading

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Colossus of Rhodes. |

| Wikisource has the text of The New Student's Reference Work article "Colossus of Rhodes". |

| Library resources about Colossus of Rhodes |

- Jones, Kenneth R. 2014. "Alcaeus of Messene, Philip V and the Colossus of Rhodes: A Re-Examination of Anth. Pal. 6.171." The Classical Quarterly 64, no. 1: 136–51. doi:10.1017/S0009838813000591.

- Romer, John., and Elizabeth Romer. 1995. The Seven Wonders of the World: A History of the Modern Imagination. 1st American ed. New York: Henry Holt.

- Woods, David. 2016. "On the Alleged Arab Destruction of the Colossus of Rhodes c. 653." Byzantion: Revue Internationale Des Etudes Byzantines 86: 441–51.

- Ancient Rhodes

- Destroyed landmarks in Greece

- Seven Wonders of the Ancient World

- Greek Antiquity in art and culture

- Hellenistic architecture

- Hellenistic and Roman bronzes

- Colossal statues

- Lost sculptures

- Culture of Rhodes

- Helios

- Ancient Greek metalwork

- Buildings and structures in Rhodes (city)

- 3rd-century BC religious buildings and structures

- Buildings and structures completed in the 3rd century BC

- Buildings and structures demolished in the 3rd century BC

- 3rd-century BC establishments

- 3rd-century BC disestablishments

No comments:

Post a Comment