The Viking connection to

the aspect of the eight-legged horse must be absolute in the draw of bridge to

past. The side to side action of horses

in war is indeed the grant of that four-legged chase to harness the next

paragraph to picture complete:

To engage the Viking as

World renowned is to appreciate the ship.

A device of times to oceans the announced is merely the system to the

sky and the traveling to the seas as oars were the template of that era. As tides rose and beaches became landings it

is perhaps as simple as complex; is Occam’s razor by choice to the best tool as

by application to the quick of flame to the story of the liver as the body of

absorption measures accuracy to chapter and verse being word to mouth instead

of foot to the 12 inch rule removing the triplex of just numbers and returning

to the route as units to simply explain the knot itself.

(The Standard of Ur (see below) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Standard_of_Ur)

Sleipnir is also mentioned in a riddle found in the 13th century legendary saga Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks, in the 13th-century legendary saga Völsunga saga as the ancestor of the horse Grani, and book I of Gesta Danorum, written in the 12th century by Saxo Grammaticus, contains an episode considered by many scholars to involve Sleipnir. Sleipnir is generally accepted as depicted on two 8th century Gotlandic image stones: the Tjängvide image stone and the Ardre VIII image stone.

Scholarly theories have been proposed regarding Sleipnir's potential connection to shamanic practices among the Norse pagans. In modern times, Sleipnir appears in Icelandic folklore as the creator of Ásbyrgi, in works of art, literature, software, and in the names of ships.

Attestations

Poetic Edda

"Odin and Sleipnir" (1911) by John Bauer.

Prose Edda

An illustration of Odin riding Sleipnir from an 18th-century Icelandic manuscript.

An 18th century Prose Edda manuscript illustration featuring Hermóðr upon Sleipnir (left), Baldr (upper right), and Hel (lower right).

In chapter 43, Sleipnir's origins are described. Gangleri (described earlier in the book as King Gylfi in disguise) asks High who the horse Sleipnir belongs to and what there is to tell about it. High expresses surprise in Gangleri's lack of knowledge about Sleipnir and its origin. High tells a story set "right at the beginning of the gods' settlement, when the gods established Midgard and built Val-Hall" about an unnamed builder who has offered to build a fortification for the gods in three seasons that will keep out invaders in exchange for the goddess Freyja, the sun, and the moon. After some debate, the gods agree to this, but place a number of restrictions on the builder, including that he must complete the work within three seasons with the help of no man. The builder makes a single request; that he may have help from his stallion Svaðilfari, and due to Loki's influence, this is allowed. The stallion Svaðilfari performs twice the deeds of strength as the builder, and hauls enormous rocks to the surprise of the gods. The builder, with Svaðilfari, makes fast progress on the wall, and three days before the deadline of summer, the builder was nearly at the entrance to the fortification. The gods convene, and figured out who was responsible, resulting in a unanimous agreement that, along with most trouble, Loki was to blame.[9]

The gods declare that Loki would deserve a horrible death if he could not find a scheme that would cause the builder to forfeit his payment, and threatened to attack him. Loki, afraid, swore oaths that he would devise a scheme to cause the builder to forfeit the payment, whatever it would cost himself. That night, the builder drove out to fetch stone with his stallion Svaðilfari, and out from a wood ran a mare. The mare neighed at Svaðilfari, and "realizing what kind of horse it was," Svaðilfari became frantic, neighed, tore apart his tackle, and ran towards the mare. The mare ran to the wood, Svaðilfari followed, and the builder chased after. The two horses ran around all night, causing the building work to be held up for the night, and the previous momentum of building work that the builder had been able to maintain was not continued.[10]

When the Æsir realize that the builder is a hrimthurs, they disregard their previous oaths with the builder, and call for Thor. Thor arrives, and kills the builder by smashing the builder's skull into shards with the hammer Mjöllnir. However, Loki had "such dealings" with Svaðilfari that "somewhat later" Loki gave birth to a grey foal with eight legs; the horse Sleipnir, "the best horse among gods and men."[10]

In chapter 49, High describes the death of the god Baldr. Hermóðr agrees to ride to Hel to offer a ransom for Baldr's return, and so "then Odin's horse Sleipnir was fetched and led forward." Hermóðr mounts Sleipnir and rides away. Hermóðr rides for nine nights in deep, dark valleys where Hermóðr can see nothing. The two arrive at the river Gjöll and then continue to Gjöll bridge, encountering a maiden guarding the bridge named Móðguðr. Some dialogue occurs between Hermóðr and Móðguðr, including that Móðguðr notes that recently there had ridden five battalions of dead men across the bridge that made less sound than he. Sleipnir and Hermóðr continue "downwards and northwards" on the road to Hel, until the two arrive at Hel's gates. Hermóðr dismounts from Sleipnir, tightens Sleipnir's girth, mounts him, and spurs Sleipnir on. Sleipnir "jumped so hard and over the gate that it came nowhere near." Hermóðr rides up to the hall, and dismounts from Sleipnir. After Hermóðr's pleas to Hel to return Baldr are accepted under a condition, Hermóðr and Baldr retrace their path backward and return to Asgard.[11]

In chapter 16 of the book Skáldskaparmál, a kenning given for Loki is "relative of Sleipnir."[12] In chapter 17, a story is provided in which Odin rides Sleipnir into the land of Jötunheimr and arrives at the residence of the jötunn Hrungnir. Hrungnir asks "what sort of person this was" wearing a golden helmet, "riding sky and sea," and says that the stranger "has a marvellously good horse." Odin wagers his head that no horse as good could be found in all of Jötunheimr. Hrungnir admitted that it was a fine horse, yet states that he owns a much longer-paced horse; Gullfaxi. Incensed, Hrungnir leaps atop Gullfaxi, intending to attack Odin for Odin's boasting. Odin gallops hard ahead of Hrungnir, and, in his, fury, Hrungnir finds himself having rushed into the gates of Asgard.[13] In chapter 58, Sleipnir is mentioned among a list of horses in Þorgrímsþula: "Hrafn and Sleipnir, splendid horses [...]".[14] In addition, Sleipnir occurs twice in kennings for "ship" (once appearing in chapter 25 in a work by the skald Refr, and "sea-Sleipnir" appearing in chapter 49 in Húsdrápa, a work by the 10th century skald Úlfr Uggason).[15]

Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks

Odin sits atop his steed Sleipnir, his ravens Huginn and Muninn and wolves Geri and Freki nearby (1895) by Lorenz Frølich.

- 36. Gestumblindi said:

- "Who are the twain

- that on ten feet run?

- three eyes they have,

- but only one tail.

- Alright guess now

- this riddle, Heithrek!"

Völsunga saga

In chapter 13 of Völsunga saga, the hero Sigurðr is on his way to a wood and he meets a long-bearded old man he had never seen before. Sigurd tells the old man that he is going to choose a horse, and asks the old man to come with him to help him decide. The old man says that they should drive the horses down to the river Busiltjörn. The two drive the horses down into the deeps of Busiltjörn, and all of the horses swim back to land but a large, young, and handsome grey horse that no one had ever mounted. The grey-bearded old man says that the horse is from "Sleipnir's kin" and that "he must be raised carefully, because he will become better than any other horse." The old man vanishes. Sigurd names the horse Grani, and the narrative adds that the old man was none other than (the god) Odin.[17]Gesta Danorum

"Hadingus and the Old Man" (1898) by Louis Moe.

In book I, the young Hadingus encounters "a certain man of great age who had lost an eye" who allies him with Liserus. Hadingus and Liserus set out to wage war on Lokerus, ruler of Kurland. Meeting defeat, the old man takes Hadingus with him onto his horse as they flee to the old man's house, and the two drink an invigorating draught. The old man sings a prophecy, and takes Hadingus back to where he found him on his horse. During the ride back, Hadingus trembles beneath the old man's mantle, and peers out of its holes. Hadingus realizes that he is flying through the air: "and he saw that before the steps of the horse lay the sea; but was told not to steal a glimpse of the forbidden thing, and therefore turned his amazed eyes from the dread spectacle of the roads that he journeyed."[19]

In book II, Biarco mentions Odin and Sleipnir: "If I may look on the awful husband of Frigg, howsoever he be covered in his white shield, and guide his tall steed, he shall in no way go safe out of Leire; it is lawful to lay low in war the war-waging god."[20]

Archaeological record

Two of the 8th century picture stones from the island of Gotland, Sweden depict eight-legged horses, which are thought by most scholars to depict Sleipnir: the Tjängvide image stone and the Ardre VIII image stone. Both stones feature a rider sitting atop an eight-legged horse, which some scholars view as Odin. Above the rider on the Tjängvide image stone is a horizontal figure holding a spear, which may be a valkyrie, and a female figure greets the rider with a cup. The scene has been interpreted as a rider arriving at the world of the dead.[21] The mid-7th century Eggja stone bearing the Odinic name haras (Old Norse 'army god') may be interpreted as depicting Sleipnir.[22]Theories

John Lindow theorizes that Sleipnir's "connection to the world of the dead grants a special poignancy to one of the kennings in which Sleipnir turns up as a horse word," referring to the skald Úlfr Uggason's usage of "sea-Sleipnir" in his Húsdrápa, which describes the funeral of Baldr. Lindow continues that "his use of Sleipnir in the kenning may show that Sleipnir's role in the failed recovery of Baldr was known at that time and place in Iceland; it certainly indicates that Sleipnir was an active participant in the mythology of the last decades of paganism." Lindow adds that the eight legs of Sleipnir "have been interpreted as an indication of great speed or as being connected in some unclear way with cult activity."[21]Hilda Ellis Davidson says that "the eight-legged horse of Odin is the typical steed of the shaman" and that in the shaman's journeys to the heavens or the underworld, a shaman "is usually represented as riding on some bird or animal." Davidson says that while the creature may vary, the horse is fairly common "in the lands where horses are in general use, and Sleipnir's ability to bear the god through the air is typical of the shaman's steed" and cites an example from a study of shamanism by Mircea Eliade of an eight-legged foal from a story of a Buryat shaman. Davidson says that while attempts have been made to connect Sleipnir with hobby horses and steeds with more than four feet that appear in carnivals and processions, but that "a more fruitful resemblance seems to be on the bier on which a dead man is carried in the funeral procession by four bearers; borne along thus, he may be described as riding on a steed with eight legs." As an example, Davidson cites a funeral dirge from the Gondi people in India as recorded by Verrier Elwin, stating that "it contains references to Bagri Maro, the horse with eight legs, and it is clear from the song that it is the dead man's bier." Davidson says that the song is sung when a distinguished Muria dies, and provides a verse:[23]

Davidson adds that the representation of Odin's steed as eight-legged could arise naturally out of such an image, and that "this is in accordance with the picture of Sleipnir as a horse that could bear its rider to the land of the dead."[23]

- What horse is this?

- It is the horse of Bagri Maro.

- What should we say of its legs?

- This horse has eight legs.

- What should we say of its heads?

- This horse has four heads. . . .

- Catch the bridle and mount the horse.[23]

Ulla Loumand cites Sleipnir and the flying horse Hófvarpnir as "prime examples" of horses in Norse mythology as being able to "mediate between earth and sky, between Ásgarðr, Miðgarðr and Útgarðr and between the world of mortal men and the underworld."[24]

The Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture theorizes that Sleipnir's eight legs may be the remnants of horse-associated divine twins found in Indo-European cultures and ultimately stemming from Proto-Indo-European religion. The encyclopedia states that "[...] Sleipnir is born with an extra set of legs, thus representing an original pair of horses. Like Freyr and Njörðr, Sleipnir is responsible for carrying the dead to the otherworld." The encyclopedia cites parallels between the birth of Sleipnir and myths originally pointing to a Celtic goddess who gave birth to the Divine horse twins. These elements include a demand for a goddess by an unwanted suitor (the hrimthurs demanding the goddess Freyja) and the seduction of builders.[25]

Modern influence

The horseshoe-shaped canyon Ásbyrgi.

See also

- Helhest, the three-legged "Hel horse" of later Scandinavian folklore

- The "táltos steed", a six-legged horse in Hungarian folklore

- Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology

- Santa Claus's eight flying reindeer.

Notes

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sleipnir. |

- Noszlopy, Waterhouse (2005:181).

References

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23285-2

- Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1990). Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Grammaticus, Saxo; Elton, Oliver (1905). The Danish History. New York: Norroena Society. (reprinted in 2005 by BiblioBazaar)

- Hollander, Lee Milton (1936). Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Nonskaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda. Columbia University Press

- Kermode, Philip Moore Callow (1904). Traces of Norse Mythology in the Isle of Man. Harvard University Press.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Loumand, Ulla (2006). "The Horse and its Role in Icelandic Burial Practices, Mythology, and Society". In Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3–7, 2004. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- Mallory, J. P. Adams, Douglas Q. (Editors) (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Noszlopy, George Thomas. Waterhouse, Fiona (2005). Public Sculpture of Staffordshire and the Black Country. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-989-4

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1

Languages

Standard of Ur

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

The Standard of Ur is a Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the British Museum.

It comprises a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (8.50 in)

wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of

shell, red limestone and lapis lazuli. It comes from the ancient city of Ur (located in modern-day Iraq west of Nasiriyah). It dates to the First Dynasty of Ur during the Early Dynastic period

and is around 4,600 years old. The standard was probably constructed in

the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace

represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although

interpreted as a standard by its discoverer, its original purpose

remains enigmatic. It was found in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s next

to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed man who may have been its

bearer.

| The Standard of Ur | |

|---|---|

"War" panel

| |

| Material | shell, limestone, lapis lazuli, bitumen |

| Writing | cuneiform |

| Created | 2600 BC |

| Discovered | Royal Cemetery |

| Present location | British Museum, London |

| Identification | 121201 Reg number:1928,1010.3 |

History

The Standard of Ur, in the British Museum.

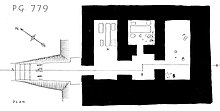

Plan of grave PG 779, thought to belong to Ur-Pabilsag. The Standard of Ur was located in "S"

Description

"Peace" panel

Inlaid mosaic panels cover each long side of the Standard. Each presents a series of scenes displayed in three registers, upper, middle and bottom. The two mosaics have been dubbed "War" and "Peace" for their subject matter, respectively a representation of a military campaign and scenes from a banquet. The panels at each end originally showed fantastical animals but they suffered significant damage while buried, though they have since been restored.

Mosaic scenes

"Peace", detail showing lyrist and possibly a singer

The lower register shows four chariots, each carrying a charioteer and a warrior (carrying either a spear or an axe) and drawn by a team of four equids. The chariots are depicted in considerable detail; each has solid wheels (spoked wheels were not invented until about 1800 BC) and carries spare spears in a container at the front. The arrangement of the equids' reins is also shown in detail, illustrating how the Sumerians harnessed them without using bits, which were only introduced a millennium later.[5] The chariot scene evolves from left to right in a way that emphasizes motion and action through changes in the depiction of the animals' gait. The first chariot team is shown walking, the second cantering, the third galloping and the fourth rearing. Trampled enemies are shown lying under the hooves of the latter three groups, symbolizing the potency of a chariot attack.[3]

"Peace" portrays a banquet scene. The king again appears in the upper register, sitting on a carved stool on the left-hand side. He is faced by six other seated participants, each holding a cup raised in his right hand. They are attended by various other figures including a long-haired individual, possibly a singer, who accompanies a lyrist. In the middle register, bald-headed figures wearing skirts with fringes parade animals, fish and other goods, perhaps bringing them to the feast. The bottom register shows a series of figures dressed and coiffed in a different way from those above, carrying produce in shoulder bags or backpacks, or leading equids by ropes attached to nose rings.[3]

Interpretations

The original function of the Standard of Ur is not conclusively understood. Woolley's suggestion that it represented a standard is now thought unlikely. It has also been speculated that it was the soundbox of a musical instrument.[2] Paola Villani suggests that it was used as a chest to store funds for warfare or civil and religious works.[10] It is, however, impossible to say for sure, as there is no inscription on the artifact to provide any background context.Although the side mosaics are usually referred to as the "war side" and "peace side", they may in fact be a single narrative – a battle followed by a victory celebration. This would be a visual parallel with the literary device of merism, used by the Sumerians, in which the totality of a situation was described through the pairing of opposite concepts.[11][12] A Sumerian ruler was considered to have a dual role as a lugal (literally "big man" or war leader) and an en or civic/religious leader, responsible for mediating with the gods and maintaining the fecundity of the land. The Standard of Ur may have been intended to depict these two complementary concepts of Sumerian kingship.[3]

| |

| Audio | |

|---|---|

| Video | |

See also

References

- Cohen, Andrew C. Death rituals, ideology, and the development of early Mesopotamian kingship: toward a new understanding of Iraq's royal cemetery of Ur, p. 92. BRILL, 2005. ISBN 978-90-04-14635-8

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Standard of Ur. |

This article is about an item held in the British Museum. The object reference is EA 121201 / Reg number: 1928,1010.3.

No comments:

Post a Comment