The Viking connection to

the aspect of the eight-legged horse must be absolute in the draw of bridge to

past. The side to side action of horses

in war is indeed the grant of that four-legged chase to harness the next

paragraph to picture complete:

To engage the Viking as

World renowned is to appreciate the ship.

A device of times to oceans the announced is merely the system to the

sky and the traveling to the seas as oars were the template of that era. As tides rose and beaches became landings it

is perhaps as simple as complex; is Occam’s razor by choice to the best tool as

by application to the quick of flame to the story of the liver as the body of

absorption measures accuracy to chapter and verse being word to mouth instead

of foot to the 12 inch rule removing the triplex of just numbers and returning

to the route as units to simply explain the knot itself.

Sleipnir

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

In

Norse mythology,

Sleipnir (

Old Norse "slippy"

[1] or "the slipper"

[2]) is an eight-legged

horse ridden by

Odin. Sleipnir is attested in the

Poetic Edda, compiled in the 13th century from earlier traditional sources, and the

Prose Edda, written in the 13th century by

Snorri Sturluson. In both sources, Sleipnir is Odin's steed, is the child of

Loki and

Svaðilfari, is described as the best of all horses, and is sometimes ridden to the location of

Hel. The

Prose Edda contains extended information regarding the circumstances of Sleipnir's birth, and details that he is grey in color.

Sleipnir is also mentioned in a riddle found in the 13th century

legendary saga Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks, in the 13th-century legendary saga

Völsunga saga as the ancestor of the horse

Grani, and book I of

Gesta Danorum, written in the 12th century by

Saxo Grammaticus,

contains an episode considered by many scholars to involve Sleipnir.

Sleipnir is generally accepted as depicted on two 8th century

Gotlandic image stones: the

Tjängvide image stone and the

Ardre VIII image stone.

Scholarly theories have been proposed regarding Sleipnir's potential connection to

shamanic practices among the

Norse pagans. In modern times, Sleipnir appears in

Icelandic folklore as the creator of

Ásbyrgi, in works of art, literature, software, and in the names of ships.

Attestations

Poetic Edda

In the

Poetic Edda, Sleipnir appears or is mentioned in the poems

Grímnismál,

Sigrdrífumál,

Baldrs draumar, and

Hyndluljóð. In

Grímnismál,

Grimnir

(Odin in disguise and not yet having revealed his identity) tells the

boy Agnar in verse that Sleipnir is the best of horses ("Odin is the

best of the

Æsir, Sleipnir of horses").

[3] In

Sigrdrífumál, the

valkyrie Sigrdrífa tells the hero

Sigurðr that

runes should be cut "on Sleipnir's teeth and on the sledge's strap-bands."

[4] In

Baldrs draumar, after the Æsir convene about the god

Baldr's bad dreams, Odin places a

saddle on Sleipnir and the two ride to the location of

Hel.

[5] The

Völuspá hin skamma section of

Hyndluljóð says that Loki produced "

the wolf" with

Angrboða, produced Sleipnir with

Svaðilfari, and thirdly "one monster that was thought the most baleful, who was descended from

Býleistr's brother."

[6]

Prose Edda

An illustration of Odin riding Sleipnir from an 18th-century Icelandic manuscript.

An 18th century Prose Edda manuscript illustration featuring Hermóðr upon Sleipnir (left), Baldr (upper right), and Hel (lower right).

In the

Prose Edda book

Gylfaginning, Sleipnir is first mentioned in chapter 15 where the enthroned figure of

High says that every day the Æsir ride across the bridge

Bifröst, and provides a list of the Æsir's horses. The list begins with Sleipnir: "best is Sleipnir, he is Odin's, he has eight legs."

[7] In chapter 41, High quotes the

Grímnismál stanza that mentions Sleipnir.

[8]

In chapter 43, Sleipnir's origins are described.

Gangleri (described earlier in the book as King

Gylfi

in disguise) asks High who the horse Sleipnir belongs to and what there

is to tell about it. High expresses surprise in Gangleri's lack of

knowledge about Sleipnir and its origin. High tells a story set "right

at the beginning of the gods' settlement, when the gods established

Midgard and built

Val-Hall"

about an unnamed builder who has offered to build a fortification for

the gods in three seasons that will keep out invaders in exchange for

the goddess

Freyja, the

sun, and the

moon.

After some debate, the gods agree to this, but place a number of

restrictions on the builder, including that he must complete the work

within three seasons with the help of no man. The builder makes a single

request; that he may have help from his stallion

Svaðilfari,

and due to Loki's influence, this is allowed. The stallion Svaðilfari

performs twice the deeds of strength as the builder, and hauls enormous

rocks to the surprise of the gods. The builder, with Svaðilfari, makes

fast progress on the wall, and three days before the deadline of summer,

the builder was nearly at the entrance to the fortification. The gods

convene, and figured out who was responsible, resulting in a unanimous

agreement that, along with most trouble, Loki was to blame.

[9]

The gods declare that Loki would deserve a horrible death if he

could not find a scheme that would cause the builder to forfeit his

payment, and threatened to attack him. Loki, afraid, swore oaths that he

would devise a scheme to cause the builder to forfeit the payment,

whatever it would cost himself. That night, the builder drove out to

fetch stone with his stallion Svaðilfari, and out from a wood ran a

mare. The mare neighed at Svaðilfari, and "realizing what kind of horse

it was," Svaðilfari became frantic, neighed, tore apart his tackle, and

ran towards the mare. The mare ran to the wood, Svaðilfari followed, and

the builder chased after. The two horses ran around all night, causing

the building work to be held up for the night, and the previous momentum

of building work that the builder had been able to maintain was not

continued.

[10]

When the Æsir realize that the builder is a

hrimthurs,

they disregard their previous oaths with the builder, and call for

Thor. Thor arrives, and kills the builder by smashing the builder's

skull into shards with the hammer

Mjöllnir. However, Loki had "such dealings" with Svaðilfari that "somewhat later" Loki gave birth to a grey

foal with eight legs; the horse Sleipnir, "the best horse among gods and men."

[10]

In chapter 49, High describes the death of the god

Baldr.

Hermóðr

agrees to ride to Hel to offer a ransom for Baldr's return, and so

"then Odin's horse Sleipnir was fetched and led forward." Hermóðr mounts

Sleipnir and rides away. Hermóðr rides for

nine nights in deep, dark valleys where Hermóðr can see nothing. The two arrive at the river

Gjöll and then continue to Gjöll bridge, encountering a maiden guarding the bridge named

Móðguðr.

Some dialogue occurs between Hermóðr and Móðguðr, including that

Móðguðr notes that recently there had ridden five battalions of dead men

across the bridge that made less sound than he. Sleipnir and Hermóðr

continue "downwards and northwards" on the road to Hel, until the two

arrive at Hel's gates. Hermóðr dismounts from Sleipnir, tightens

Sleipnir's

girth,

mounts him, and spurs Sleipnir on. Sleipnir "jumped so hard and over

the gate that it came nowhere near." Hermóðr rides up to the hall, and

dismounts from Sleipnir. After Hermóðr's pleas to

Hel to return Baldr are accepted under a condition, Hermóðr and Baldr retrace their path backward and return to

Asgard.

[11]

In chapter 16 of the book

Skáldskaparmál, a

kenning given for Loki is "relative of Sleipnir."

[12] In chapter 17, a story is provided in which Odin rides Sleipnir into the land of

Jötunheimr and arrives at the residence of the

jötunn Hrungnir.

Hrungnir asks "what sort of person this was" wearing a golden helmet,

"riding sky and sea," and says that the stranger "has a marvellously

good horse." Odin wagers his head that no horse as good could be found

in all of Jötunheimr. Hrungnir admitted that it was a fine horse, yet

states that he owns a much longer-paced horse;

Gullfaxi.

Incensed, Hrungnir leaps atop Gullfaxi, intending to attack Odin for

Odin's boasting. Odin gallops hard ahead of Hrungnir, and, in his, fury,

Hrungnir finds himself having rushed into the gates of Asgard.

[13] In chapter 58, Sleipnir is mentioned among a list of horses in

Þorgrímsþula: "Hrafn and Sleipnir, splendid horses [...]".

[14] In addition, Sleipnir occurs twice in kennings for "

ship" (once appearing in chapter 25 in a work by the

skald Refr, and "sea-Sleipnir" appearing in chapter 49 in

Húsdrápa, a work by the 10th century skald

Úlfr Uggason).

[15]

Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks

In

Hervarar saga ok Heiðreks, the poem

Heiðreks gátur contains a riddle that mentions Sleipnir and Odin:

- 36. Gestumblindi said:

- "Who are the twain

- that on ten feet run?

- three eyes they have,

- but only one tail.

- Alright guess now

- this riddle, Heithrek!"

- Heithrek said:

- "Good is thy riddle, Gestumblindi,

- and guessed it is:

- that is Odin riding on Sleipnir."[16]

Völsunga saga

In chapter 13 of

Völsunga saga, the hero

Sigurðr is on his way to a wood and he meets a

long-bearded old man

he had never seen before. Sigurd tells the old man that he is going to

choose a horse, and asks the old man to come with him to help him

decide. The old man says that they should drive the horses down to the

river Busiltjörn. The two drive the horses down into the deeps of

Busiltjörn, and all of the horses swim back to land but a large, young,

and handsome grey horse that no one had ever mounted. The grey-bearded

old man says that the horse is from "Sleipnir's kin" and that "he must

be raised carefully, because he will become better than any other

horse." The old man vanishes. Sigurd names the horse

Grani, and the narrative adds that the old man was none other than (the god)

Odin.

[17]

Gesta Danorum

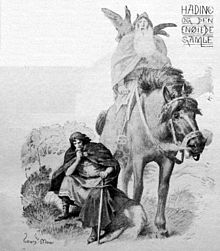

"Hadingus and the Old Man" (1898) by

Louis Moe.

Sleipnir is generally considered as appearing in a sequence of events described in book I of

Gesta Danorum.

[18]

In book I, the young

Hadingus

encounters "a certain man of great age who had lost an eye" who allies

him with Liserus. Hadingus and Liserus set out to wage war on Lokerus,

ruler of

Kurland.

Meeting defeat, the old man takes Hadingus with him onto his horse as

they flee to the old man's house, and the two drink an invigorating

draught. The old man sings a prophecy, and takes Hadingus back to where

he found him on his horse. During the ride back, Hadingus trembles

beneath the old man's

mantle,

and peers out of its holes. Hadingus realizes that he is flying through

the air: "and he saw that before the steps of the horse lay the sea;

but was told not to steal a glimpse of the forbidden thing, and

therefore turned his amazed eyes from the dread spectacle of the roads

that he journeyed."

[19]

In book II,

Biarco mentions Odin and Sleipnir: "If I may look on the awful husband of

Frigg, howsoever he be covered in his white shield, and guide his tall steed, he shall in no way go safe out of

Leire; it is lawful to lay low in war the war-waging god."

[20]

Archaeological record

Two of the 8th century

picture stones from the island of

Gotland,

Sweden depict eight-legged horses, which are thought by most scholars to depict Sleipnir: the

Tjängvide image stone and the

Ardre VIII image stone.

Both stones feature a rider sitting atop an eight-legged horse, which

some scholars view as Odin. Above the rider on the Tjängvide image stone

is a horizontal figure holding a spear, which may be a

valkyrie, and a female figure greets the rider with a cup. The scene has been interpreted as a rider arriving at the world of the dead.

[21] The mid-7th century

Eggja stone bearing the

Odinic name haras (

Old Norse 'army god') may be interpreted as depicting Sleipnir.

[22]

Detail of figure riding an eight-legged horse on the Tjängvide image stone

The Ardre VIII image stone

Theories

John Lindow

theorizes that Sleipnir's "connection to the world of the dead grants a

special poignancy to one of the kennings in which Sleipnir turns up as a

horse word," referring to the skald Úlfr Uggason's usage of

"sea-Sleipnir" in his

Húsdrápa, which describes the funeral of

Baldr. Lindow continues that "his use of Sleipnir in the kenning may

show that Sleipnir's role in the failed recovery of Baldr was known at

that time and place in Iceland; it certainly indicates that Sleipnir was

an active participant in the mythology of the last decades of

paganism." Lindow adds that the eight legs of Sleipnir "have been

interpreted as an indication of great speed or as being connected in

some unclear way with cult activity."

[21]

Hilda Ellis Davidson

says that "the eight-legged horse of Odin is the typical steed of the

shaman" and that in the shaman's journeys to the heavens or the

underworld, a shaman "is usually represented as riding on some bird or

animal." Davidson says that while the creature may vary, the horse is

fairly common "in the lands where horses are in general use, and

Sleipnir's ability to bear the god through the air is typical of the

shaman's steed" and cites an example from a study of shamanism by

Mircea Eliade of an eight-legged foal from a story of a

Buryat shaman. Davidson says that while attempts have been made to connect Sleipnir with

hobby horses

and steeds with more than four feet that appear in carnivals and

processions, but that "a more fruitful resemblance seems to be on the

bier

on which a dead man is carried in the funeral procession by four

bearers; borne along thus, he may be described as riding on a steed with

eight legs." As an example, Davidson cites a funeral

dirge from the

Gondi people in

India as recorded by

Verrier Elwin, stating that "it contains references to

Bagri Maro,

the horse with eight legs, and it is clear from the song that it is the

dead man's bier." Davidson says that the song is sung when a

distinguished

Muria dies, and provides a verse:

[23]

- What horse is this?

- It is the horse of Bagri Maro.

- What should we say of its legs?

- This horse has eight legs.

- What should we say of its heads?

- This horse has four heads. . . .

- Catch the bridle and mount the horse.[23]

Davidson adds that the representation of Odin's steed as eight-legged

could arise naturally out of such an image, and that "this is in

accordance with the picture of Sleipnir as a horse that could bear its

rider to the land of the dead."

[23]

Ulla Loumand cites Sleipnir and the flying horse

Hófvarpnir as "prime examples" of horses in Norse mythology as being able to "mediate between earth and sky, between

Ásgarðr,

Miðgarðr and

Útgarðr and between the world of mortal men and the underworld."

[24]

The

Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture theorizes that Sleipnir's eight legs may be the remnants of horse-associated

divine twins found in

Indo-European cultures and ultimately stemming from

Proto-Indo-European religion.

The encyclopedia states that "[...] Sleipnir is born with an extra set

of legs, thus representing an original pair of horses. Like

Freyr and

Njörðr,

Sleipnir is responsible for carrying the dead to the otherworld." The

encyclopedia cites parallels between the birth of Sleipnir and myths

originally pointing to a

Celtic goddess who gave birth to the Divine horse twins. These elements include a demand for a goddess by an unwanted suitor (the

hrimthurs demanding the goddess

Freyja) and the seduction of builders.

[25]

Modern influence

The horseshoe-shaped canyon

Ásbyrgi.

According to Icelandic folklore, the

horseshoe-shaped canyon

Ásbyrgi located in

Jökulsárgljúfur National Park, northern

Iceland was formed by Sleipnir's hoof.

[26] Sleipnir is depicted with Odin on

Dagfin Werenskiold's wooden relief

Odin på Sleipnir (1945–1950) on the exterior of the

Oslo City Hall in

Oslo,

Norway.

[27] Sleipnir has been and remains a popular name for ships in northern Europe, and

Rudyard Kipling's short story entitled

Sleipnir, late Thurinda (1888) features a horse named Sleipnir.

[28][26] A statue of Sleipnir (1998) stands in

Wednesbury,

England, a town which takes its name from the

Anglo-Saxon version of Odin,

Wōden.

[29]

See also

- Helhest, the three-legged "Hel horse" of later Scandinavian folklore

- The "táltos steed", a six-legged horse in Hungarian folklore

- Pegasus, the winged horse of Greek mythology

- Santa Claus's eight flying reindeer.

Notes

|

Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sleipnir. |

Orchard (1997:151).

- Noszlopy, Waterhouse (2005:181).

References

- Byock, Jesse (Trans.) (1990). The Saga of the Volsungs: The Norse Epic of Sigurd the Dragon Slayer. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-23285-2

- Ellis Davidson, H. R. (1990). Gods And Myths Of Northern Europe. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-013627-4

- Faulkes, Anthony (Trans.) (1995). Edda. Everyman. ISBN 0-460-87616-3

- Grammaticus, Saxo; Elton, Oliver (1905). The Danish History. New York: Norroena Society. (reprinted in 2005 by BiblioBazaar)

- Hollander, Lee Milton (1936). Old Norse Poems: The Most Important Nonskaldic Verse Not Included in the Poetic Edda. Columbia University Press

- Kermode, Philip Moore Callow (1904). Traces of Norse Mythology in the Isle of Man. Harvard University Press.

- Larrington, Carolyne (Trans.) (1999). The Poetic Edda. Oxford World's Classics. ISBN 0-19-283946-2

- Lindow, John (2001). Norse Mythology: A Guide to the Gods, Heroes, Rituals, and Beliefs. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-515382-0

- Loumand, Ulla (2006). "The Horse and its

Role in Icelandic Burial Practices, Mythology, and Society". In

Andrén, Anders; Jennbert, Kristina; et al. (eds.). Old

Norse Religion in Long Term Perspectives: Origins, Changes and

Interactions, an International Conference in Lund, Sweden, June 3–7,

2004. Lund: Nordic Academic Press. ISBN 91-89116-81-X.

- Mallory, J. P. Adams, Douglas Q. (Editors) (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 1-884964-98-2

- Noszlopy, George Thomas. Waterhouse, Fiona (2005). Public Sculpture of Staffordshire and the Black Country. Liverpool University Press. ISBN 0-85323-989-4

- Orchard, Andy (1997). Dictionary of Norse Myth and Legend. Cassell. ISBN 0-304-34520-2

- Simek, Rudolf (2007) translated by Angela Hall. Dictionary of Northern Mythology. D.S. Brewer. ISBN 0-85991-513-1

Languages

Kermode (1904:6).

Larrington (1999:58).

Larrington (1999:169).

Larrington (1999:243).

Larrington (1999:258).

Faulkes (1995:18).

Faulkes (1995:34).

Faulkes (1995:35).

Faulkes (1995:36).

Faulkes (1995:49–50).

Faulkes (1995:76).

Faulkes (1995:77).

Faulkes (1995:136).

Faulkes (1995:92 and 121).

Hollander (1936:99).

Byock (1990:56).

Lindow (2001:276–277).

Grammaticus & Elton (2006:104–105).

Grammaticus & Elton (2006:147).

Lindow (2001:277).

Simek (2007:140).

Davidson (1990:142–143).

Loumand (2006:133).

Mallory. Adams (1997:163).

Simek (2007:294).

Municipality of Oslo (2001-06-26). "Yggdrasilfrisen" (in Norwegian). Archived from the original on 2009-01-25. Retrieved 2008-12-02.

Kipling, Rudyard (1909). Abaft the Funnel. New York: B. W. Dodge & Company. Retrieved March 16, 2014.

Standard of Ur

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

The

Standard of Ur is a

Sumerian artifact of the 3rd millennium BC that is now in the collection of the

British Museum.

It comprises a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59 centimetres (8.50 in)

wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid with a mosaic of

shell, red limestone and

lapis lazuli. It comes from the ancient city of

Ur (located in modern-day

Iraq west of

Nasiriyah). It dates to the

First Dynasty of Ur during the

Early Dynastic period

and is around 4,600 years old. The standard was probably constructed in

the form of a hollow wooden box with scenes of war and peace

represented on each side through elaborately inlaid mosaics. Although

interpreted as a standard by its discoverer, its original purpose

remains enigmatic. It was found in a royal tomb in Ur in the 1920s next

to the skeleton of a ritually sacrificed man who may have been its

bearer.

History

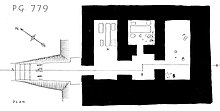

The Standard of Ur, in the British Museum.

The artifact was found in one of the largest royal tombs in the

Royal Cemetery at Ur, tomb PG 779, associated with

Ur-Pabilsag, a king who died around 2550 BC.

[1] Sir

Leonard Woolley's excavations in

Mesopotamia

in 1927–28 uncovered the artifact in the corner of a chamber, lying

close to the shoulder of a man who may have held it on a pole.

[2] For this reason, Woolley interpreted it as a

standard, giving the object its popular name, although subsequent investigation has failed to confirm this assumption.

[3]

The discovery was quite unexpected, as the tomb in which it occurred

had been thoroughly plundered by robbers in ancient times. As one corner

of the last chamber was being cleared, a workman spotted a piece of

shell inlay. Woolley later recalled that "the next minute the foreman's

hand, carefully brushing away the earth, laid bare the corner of a

mosaic in lapis lazuli and shell."

[4]

Plan of grave PG 779, thought to belong to

Ur-Pabilsag. The Standard of Ur was located in "S"

The Standard of Ur survived in only a fragmentary condition. The

ravages of time over more than four thousand years caused the decay of

the wooden frame and

bitumen glue which had cemented the mosaics in place. The soil's weight crushed the object, fragmenting it and breaking its end panels.

[2]

This made excavating the Standard a challenging task. Woolley's

excavators were instructed to look for hollows in the ground created by

decayed objects and to fill them with plaster or wax to record the shape

of the objects that had once filled them, rather like the famous

plaster casts of the victims of

Pompeii.

[5]

When the remains of the Standard were discovered by the excavators,

they found that the mosaic pieces had kept their form in the soil, while

their wooden frame had disintegrated. They carefully uncovered small

sections measuring about 3 square centimetres (0.47 sq in) and covered

them with wax, enabling the mosaics to be lifted while maintaining their

original designs.

[6]

Description

The present form of the artifact is a reconstruction, presenting a best guess of its original appearance.

[2]

It has been interpreted as a hollow wooden box measuring 21.59

centimetres (8.50 in) wide by 49.53 centimetres (19.50 in) long, inlaid

with a

mosaic of shell, red

limestone and

lapis lazuli.

The box has an irregular shape with end pieces in the shape of

truncated triangles, making it wider at the bottom than at the top,

along the lines of a

Toblerone bar.

[3]

Inlaid mosaic panels cover each long side of the Standard. Each

presents a series of scenes displayed in three registers, upper, middle

and bottom. The two mosaics have been dubbed "War" and "Peace" for their

subject matter, respectively a representation of a military campaign

and scenes from a banquet. The panels at each end originally showed

fantastical animals but they suffered significant damage while buried,

though they have since been restored.

Mosaic scenes

"Peace", detail showing

lyrist and possibly a singer

"War" is one of the earliest representations of a Sumerian army,

engaged in what is believed to be a border skirmish and its aftermath.

The "War" panel shows the king in the middle of the top register,

standing taller than any other figure, with his head projecting out of

the frame to emphasize his supreme status – a device also used on the

other panel. He stands in front of his bodyguard and a four-wheeled

chariot, drawn by a team of some sort of

equids (possibly

onagers or domestic

asses;

[7] horses were only introduced in the 2nd millennium BC after being imported from Central Asia

[8]).

He faces a row of prisoners, all of whom are portrayed as naked, bound

and injured with large, bleeding gashes on their chests and thighs – a

device indicating defeat and debasement.

[3]

In the middle register, eight virtually identically depicted soldiers

give way to a battle scene, followed by a depiction of enemies being

captured and led away. The soldiers are shown wearing leather cloaks and

helmets; actual examples of the sort of helmet depicted in the mosaic

were found in the same tomb.

[5]

The nudity of the captive and dead enemies was probably not meant to

depict literally how they appeared in real life, but was more likely to

have been symbolic and associated with a Mesopotamian belief that linked

death with nakedness.

[9]

The lower register shows four chariots, each carrying a

charioteer and a warrior (carrying either a spear or an axe) and drawn

by a team of four equids. The chariots are depicted in considerable

detail; each has solid wheels (spoked wheels were not invented until

about 1800 BC) and carries spare spears in a container at the front. The

arrangement of the equids' reins is also shown in detail, illustrating

how the Sumerians harnessed them without using

bits, which were only introduced a millennium later.

[5]

The chariot scene evolves from left to right in a way that emphasizes

motion and action through changes in the depiction of the animals' gait.

The first chariot team is shown walking, the second cantering, the

third galloping and the fourth rearing. Trampled enemies are shown lying

under the hooves of the latter three groups, symbolizing the potency of

a chariot attack.

[3]

"Peace" portrays a banquet scene. The king again appears in the

upper register, sitting on a carved stool on the left-hand side. He is

faced by six other seated participants, each holding a cup raised in his

right hand. They are attended by various other figures including a

long-haired individual, possibly a singer, who accompanies a

lyrist.

In the middle register, bald-headed figures wearing skirts with fringes

parade animals, fish and other goods, perhaps bringing them to the

feast. The bottom register shows a series of figures dressed and coiffed

in a different way from those above, carrying produce in shoulder bags

or backpacks, or leading equids by ropes attached to nose rings.

[3]

Interpretations

The

original function of the Standard of Ur is not conclusively understood.

Woolley's suggestion that it represented a standard is now thought

unlikely. It has also been speculated that it was the soundbox of a

musical instrument.

[2] Paola Villani suggests that it was used as a chest to store funds for warfare or civil and religious works.

[10] It is, however, impossible to say for sure, as there is no inscription on the artifact to provide any background context.

Although the side mosaics are usually referred to as the "war

side" and "peace side", they may in fact be a single narrative – a

battle followed by a victory celebration. This would be a visual

parallel with the literary device of

merism, used by the Sumerians, in which the totality of a situation was described through the pairing of opposite concepts.

[11][12] A

Sumerian ruler was considered to have a dual role as a

lugal (literally "big man" or war leader) and an

en

or civic/religious leader, responsible for mediating with the gods and

maintaining the fecundity of the land. The Standard of Ur may have been

intended to depict these two complementary concepts of Sumerian

kingship.

[3]

The scenes depicted in the mosaics were reflected in the tombs where

the "Standard" was found. The skeletons of attendants and musicians were

found accompanying the remains of the kings, as was equipment used in

both the "War" and "Peace" scenes of the mosaics. Unlike ancient

Egyptian tombs, the dead were not buried with provisions of food and

serving equipment; instead, they were found with the remains of meals,

such as empty food vessels and animal bones. They may have participated

in one last ritual feast, the remains of which were buried alongside

them, before being put to death (possibly by poisoning) to accompany

their master in the afterlife.

[14]

See also

References

Hamblin, William James. Warfare in the ancient Near East to 1600 BC: holy warriors at the dawn of history, p. 49. Taylor & Francis, 2006. ISBN 978-0-415-25588-2

- Cohen, Andrew C. Death

rituals, ideology, and the development of early Mesopotamian kingship:

toward a new understanding of Iraq's royal cemetery of Ur, p. 92. BRILL, 2005. ISBN 978-90-04-14635-8

External links

|

|

|---|

| Building |

|

|---|

Departments

and objects |

|

|---|

| Other |

|

|---|

|

|

Languages

The Standard of Ur, British Museum. Accessed 2010-12-05.

Zettler, Richard L.; Horne, Lee; Hansen, Donald P.; Pittman, Holly. Treasures from the royal tombs of Ur, pp. 45-47. UPenn Museum of Archaeology, 1998. ISBN 978-0-924171-54-3

Woolley, Leonard (1965). Excavations at Ur: a record of twelve years' work. Crowell. p. 86.

Collon, Dominique. Ancient Near Eastern Art, p. 65. University of California Press, 1995. ISBN 978-0-520-20307-5

Chadwick, Robert (1996). First Civilizations: Ancient Mesopotamia and Ancient Egypt. Editions Champ Fleury. ISBN 9780969847113.

Clutton-Brock, Juliet (1992). Horse Power: A History of the Horse and the Donkey in Human Societies. U.S.: Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-40646-9.

Gates, Charles (2003). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Routledge. p. 48. ISBN 9780415121828.

Bahrani, Zainab (2001). Women of Babylon: Gender and Representation in Mesopotamia. Routledge. p. 60. ISBN 9780415218306.

Settemila anni di strade. Milano: Edi-Cem. 2010.

Harrison, R.K. "Genesis", p. 441 in Bromiley, Geoffrey W. (ed.), International Standard Bible Encyclopedia: E-J. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing, 1982. ISBN 978-0-8028-3782-0

Kleiner, Fred S. Gardner's Art Through the Ages: The Western Perspective, p. 24. Cengage Learning, 2009. ISBN 978-0-495-57360-9

"The Standard of Ur". Smarthistory at Khan Academy. Retrieved March 27, 2013.