What expansion of the mind stills the frame to picture a stroke of the brush that plastered the Universe with the paints of planets as the elements shone to the photograph in a museum? As the addition touches the bare to rough draw I say note is a tone that paints explain in simplicity. Sort through a thought as the measure is air in ounces and the bucket bares the balance. Sand may be counted in grain, the beach in gallons as the moisture again changes the weight and not the measure, this is the missing piece.

Mankind is not humanity and yet the shoulder loads as the blade of grass represents the vertebrae of mathematics on the lung in fold. To envelope a sheet is to understand more than the fiber of the weave that grain is counted as thread? No, as the silk is represented again by weight as the spider is able to capture our attention in the detail by designed so specifically that the spider himself must have a brain to discuss. Conversation again brings to the dinner table the salt, oceans of salts makes the counted grain a discussion as is it a grain of salt or a count of sand?

The fact that Pi is a sign that represents nothing different than the Fibonacci numbering is odd to the fact that popular science says it is a circle as Pi at the π is the 'one in three' observation. As written

1 in 3

1

3.1415 and so on yet that does not seem to make a circle. With today's computer the observation

3 3

1

would bring on a magnificent figure of certainly beautiful symmetry possibly even explaining in simplicity dimensional shells. I wonder why physicists keep saying that

π is a circle?

Pythagoras five solids may produce for the technician an interesting beginning template:

Fibonacci number

A tiling with squares whose side lengths are successive Fibonacci numbers

The Fibonacci spiral: an approximation of the golden spiral created by drawing circular arcs connecting the opposite corners of squares in the Fibonacci tiling;[4] this one uses squares of sizes 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 and 21.

The sequence Fn of Fibonacci numbers is defined by the recurrence relation:

Jump to navigation

Jump to search

In three-dimensional space, a Platonic solid is a regular, convex polyhedron. It is constructed by congruent (identical in shape and size) regular (all angles equal and all sides equal) polygonal faces with the same number of faces meeting at each vertex. Five solids meet these criteria:

Geometers have studied the Platonic solids for thousands of years.[1] They are named for the ancient Greek philosopher Plato who hypothesized in his dialogue, the Timaeus, that the classical elements were made of these regular solids.[2]

| Tetrahedron | Cube | Octahedron | Dodecahedron | Icosahedron |

| Four faces | Six faces | Eight faces | Twelve faces | Twenty faces |

(Animation) (3D model) |

(Animation) (3D model) |

(Animation) (3D model) |

(Animation) (3D model) |

(Animation) (3D model) |

Contents

History

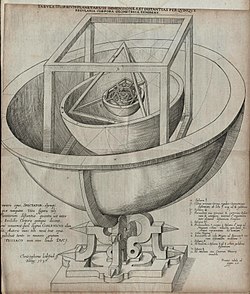

Assignment to the elements in Kepler's Mysterium Cosmographicum

The ancient Greeks studied the Platonic solids extensively. Some sources (such as Proclus) credit Pythagoras with their discovery. Other evidence suggests that he may have only been familiar with the tetrahedron, cube, and dodecahedron and that the discovery of the octahedron and icosahedron belong to Theaetetus, a contemporary of Plato. In any case, Theaetetus gave a mathematical description of all five and may have been responsible for the first known proof that no other convex regular polyhedra exist.

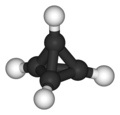

The Platonic solids are prominent in the philosophy of Plato, their namesake. Plato wrote about them in the dialogue Timaeus c.360 B.C. in which he associated each of the four classical elements (earth, air, water, and fire) with a regular solid. Earth was associated with the cube, air with the octahedron, water with the icosahedron, and fire with the tetrahedron. There was intuitive justification for these associations: the heat of fire feels sharp and stabbing (like little tetrahedra). Air is made of the octahedron; its minuscule components are so smooth that one can barely feel it. Water, the icosahedron, flows out of one's hand when picked up, as if it is made of tiny little balls. By contrast, a highly nonspherical solid, the hexahedron (cube) represents "earth". These clumsy little solids cause dirt to crumble and break when picked up in stark difference to the smooth flow of water.[citation needed] Moreover, the cube's being the only regular solid that tessellates Euclidean space was believed to cause the solidity of the Earth.

Of the fifth Platonic solid, the dodecahedron, Plato obscurely remarks, "...the god used [it] for arranging the constellations on the whole heaven". Aristotle added a fifth element, aithēr (aether in Latin, "ether" in English) and postulated that the heavens were made of this element, but he had no interest in matching it with Plato's fifth solid.[4]

Euclid completely mathematically described the Platonic solids in the Elements, the last book (Book XIII) of which is devoted to their properties. Propositions 13–17 in Book XIII describe the construction of the tetrahedron, octahedron, cube, icosahedron, and dodecahedron in that order. For each solid Euclid finds the ratio of the diameter of the circumscribed sphere to the edge length. In Proposition 18 he argues that there are no further convex regular polyhedra. Andreas Speiser has advocated the view that the construction of the 5 regular solids is the chief goal of the deductive system canonized in the Elements.[5] Much of the information in Book XIII is probably derived from the work of Theaetetus.

In the 16th century, the German astronomer Johannes Kepler attempted to relate the five extraterrestrial planets known at that time to the five Platonic solids. In Mysterium Cosmographicum, published in 1596, Kepler proposed a model of the Solar System in which the five solids were set inside one another and separated by a series of inscribed and circumscribed spheres. Kepler proposed that the distance relationships between the six planets known at that time could be understood in terms of the five Platonic solids enclosed within a sphere that represented the orbit of Saturn. The six spheres each corresponded to one of the planets (Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, and Saturn). The solids were ordered with the innermost being the octahedron, followed by the icosahedron, dodecahedron, tetrahedron, and finally the cube, thereby dictating the structure of the solar system and the distance relationships between the planets by the Platonic solids. In the end, Kepler's original idea had to be abandoned, but out of his research came his three laws of orbital dynamics, the first of which was that the orbits of planets are ellipses rather than circles, changing the course of physics and astronomy. He also discovered the Kepler solids.

In the 20th century, attempts to link Platonic solids to the physical world were expanded to the electron shell model in chemistry by Robert Moon in a theory known as the "Moon model".[6]

Cartesian coordinates

For Platonic solids centered at the origin, simple Cartesian coordinates of the vertices are given below. The Greek letter φ is used to represent the golden ratio 1 + √5/2 ≈ 1.6180.half of the sign and position permutation of coordinates.

These coordinates reveal certain relationships between the Platonic solids: the vertices of the tetrahedron represent half of those of the cube, as {4,3} or

The coordinates of the icosahedron are related to two alternated sets of coordinates of a nonuniform truncated octahedron, t{3,4} or

Eight of the vertices of the dodecahedron are shared with the cube. Completing all orientations leads to the compound of five cubes.

Combinatorial properties

A convex polyhedron is a Platonic solid if and only if- all its faces are congruent convex regular polygons,

- none of its faces intersect except at their edges, and

- the same number of faces meet at each of its vertices.

- p is the number of edges (or, equivalently, vertices) of each face, and

- q is the number of faces (or, equivalently, edges) that meet at each vertex.

| Polyhedron | Vertices | Edges | Faces | Schläfli symbol | Vertex configuration | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetrahedron | 4 | 6 | 4 | {3, 3} | 3.3.3 | |

| cube |

|

8 | 12 | 6 | {4, 3} | 4.4.4 |

| octahedron |

|

6 | 12 | 8 | {3, 4} | 3.3.3.3 |

| dodecahedron |

|

20 | 30 | 12 | {5, 3} | 5.5.5 |

| icosahedron | 12 | 30 | 20 | {3, 5} | 3.3.3.3.3 | |

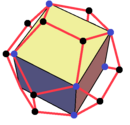

One possible Hamiltonian cycle through every vertex of a dodecahedron is shown in red – like all platonic solids, the dodecahedron is Hamiltonian

As a configuration

The elements of the platonic solids can be expressed in a configuration matrix. The diagonal elements represent the number of vertices, edges, and faces (f-vectors). The nondiagonal elements represent the number of row elements are incident to the column element. For example the top row shows a vertex has q edges and q faces incident, and the bottom row shows a face has p vertices, and p edges. And the middle row show an edge has 2 vertices, and 2 faces. Dual pairs of platonic solids have their configurations matrixes rotated 180 degrees from each other.[7]| {p,q} | Platonic configurations | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| group order: g = 8pq/(4-(p-2)(q-2)) |

g=24 | g=48 | g=120 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Classification

The classical result is that only five convex regular polyhedra exist. Two common arguments below demonstrate no more than five Platonic solids can exist, but positively demonstrating the existence of any given solid is a separate question—one that requires an explicit construction.Geometric proof

{3,3} Defect 180° |

{3,4} Defect 120° |

{3,5} Defect 60° |

{3,6} Defect 0° |

{4,3} Defect 90° |

{4,4} Defect 0° |

{5,3} Defect 36° |

{6,3} Defect 0° |

| A vertex needs at least 3 faces, and an angle defect. A 0° angle defect will fill the Euclidean plane with a regular tiling. By Descartes' theorem, the number of vertices is 720°/defect. | |||

- Each vertex of the solid must be a vertex for at least three faces.

- At each vertex of the solid, the total, among the adjacent faces, of the angles between their respective adjacent sides must be less than 360°. The amount less than 360° is called an angle defect.

- The angles at all vertices of all faces of a Platonic solid are identical: each vertex of each face must contribute less than 360°/3 = 120°.

- Regular polygons of six

or more sides have only angles of 120° or more, so the common face must

be the triangle, square, or pentagon. For these different shapes of

faces the following holds:

- Triangular faces: Each vertex of a regular triangle is 60°, so a shape may have 3, 4, or 5 triangles meeting at a vertex; these are the tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron respectively.

- Square faces: Each vertex of a square is 90°, so there is only one arrangement possible with three faces at a vertex, the cube.

- Pentagonal faces: Each vertex is 108°; again, only one arrangement of three faces at a vertex is possible, the dodecahedron.

-

- Altogether this makes 5 possible Platonic solids.

Topological proof

A purely topological proof can be made using only combinatorial information about the solids. The key is Euler's observation that V − E + F = 2, and the fact that pF = 2E = qV, where p stands for the number of edges of each face and q for the number of edges meeting at each vertex. Combining these equations one obtains the equation- {3, 3}, {4, 3}, {3, 4}, {5, 3}, {3, 5}.

Geometric properties

Angles

There are a number of angles associated with each Platonic solid. The dihedral angle is the interior angle between any two face planes. The dihedral angle, θ, of the solid {p,q} is given by the formulaThe angular deficiency at the vertex of a polyhedron is the difference between the sum of the face-angles at that vertex and 2π. The defect, δ, at any vertex of the Platonic solids {p,q} is

The 3-dimensional analog of a plane angle is a solid angle. The solid angle, Ω, at the vertex of a Platonic solid is given in terms of the dihedral angle by

The solid angle of a face subtended from the center of a platonic solid is equal to the solid angle of a full sphere (4π steradians) divided by the number of faces. Note that this is equal to the angular deficiency of its dual.

The various angles associated with the Platonic solids are tabulated below. The numerical values of the solid angles are given in steradians. The constant φ = 1 + √5/2 is the golden ratio.

| Polyhedron | Dihedral angle (θ) |

tan θ/2 | Defect (δ) | Vertex solid angle (Ω) | Face solid angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetrahedron | 70.53° |  |

|

|

|

| cube | 90° |  |

|

|

|

| octahedron | 109.47° |  |

|

|

|

| dodecahedron | 116.57° |  |

|

|

|

| icosahedron | 138.19° |  |

|

|

|

Radii, area, and volume

Another virtue of regularity is that the Platonic solids all possess three concentric spheres:- the circumscribed sphere that passes through all the vertices,

- the midsphere that is tangent to each edge at the midpoint of the edge, and

- the inscribed sphere that is tangent to each face at the center of the face.

| Polyhedron (a = 2) |

Inradius (r) | Midradius (ρ) | Circumradius (R) | Surface area (A) | Volume (V) | Volume (unit edges) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| tetrahedron |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| cube |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| octahedron |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| dodecahedron |  |

|

|

|

|

|

| icosahedron |  |

|

|

|

|

|

Symmetry

Dual polyhedra

Every polyhedron has a dual (or "polar") polyhedron with faces and vertices interchanged. The dual of every Platonic solid is another Platonic solid, so that we can arrange the five solids into dual pairs.- The tetrahedron is self-dual (i.e. its dual is another tetrahedron).

- The cube and the octahedron form a dual pair.

- The dodecahedron and the icosahedron form a dual pair.

One can construct the dual polyhedron by taking the vertices of the dual to be the centers of the faces of the original figure. Connecting the centers of adjacent faces in the original forms the edges of the dual and thereby interchanges the number of faces and vertices while maintaining the number of edges.

More generally, one can dualize a Platonic solid with respect to a sphere of radius d concentric with the solid. The radii (R, ρ, r) of a solid and those of its dual (R*, ρ*, r*) are related by

Symmetry groups

In mathematics, the concept of symmetry is studied with the notion of a mathematical group. Every polyhedron has an associated symmetry group, which is the set of all transformations (Euclidean isometries) which leave the polyhedron invariant. The order of the symmetry group is the number of symmetries of the polyhedron. One often distinguishes between the full symmetry group, which includes reflections, and the proper symmetry group, which includes only rotations.The symmetry groups of the Platonic solids are a special class of three-dimensional point groups known as polyhedral groups. The high degree of symmetry of the Platonic solids can be interpreted in a number of ways. Most importantly, the vertices of each solid are all equivalent under the action of the symmetry group, as are the edges and faces. One says the action of the symmetry group is transitive on the vertices, edges, and faces. In fact, this is another way of defining regularity of a polyhedron: a polyhedron is regular if and only if it is vertex-uniform, edge-uniform, and face-uniform.

There are only three symmetry groups associated with the Platonic solids rather than five, since the symmetry group of any polyhedron coincides with that of its dual. This is easily seen by examining the construction of the dual polyhedron. Any symmetry of the original must be a symmetry of the dual and vice versa. The three polyhedral groups are:

- the tetrahedral group T,

- the octahedral group O (which is also the symmetry group of the cube), and

- the icosahedral group I (which is also the symmetry group of the dodecahedron).

The following table lists the various symmetry properties of the Platonic solids. The symmetry groups listed are the full groups with the rotation subgroups given in parenthesis (likewise for the number of symmetries). Wythoff's kaleidoscope construction is a method for constructing polyhedra directly from their symmetry groups. They are listed for reference Wythoff's symbol for each of the Platonic solids.

| Polyhedron | Schläfli symbol |

Wythoff symbol |

Dual polyhedron |

Symmetry group (Reflection, rotation) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Polyhedral | Schön. | Cox. | Orb. | Order | ||||

| tetrahedron | {3, 3} | 3 | 2 3 | tetrahedron | Tetrahedral |

Td T |

[3,3] [3,3]+ |

*332 332 |

24 12 |

| cube | {4, 3} | 3 | 2 4 | octahedron | Octahedral |

Oh O |

[4,3] [4,3]+ |

*432 432 |

48 24 |

| octahedron | {3, 4} | 4 | 2 3 | cube | |||||

| dodecahedron | {5, 3} | 3 | 2 5 | icosahedron | Icosahedral |

Ih I |

[5,3] [5,3]+ |

*532 532 |

120 60 |

| icosahedron | {3, 5} | 5 | 2 3 | dodecahedron | |||||

In nature and technology

This section does not cite any sources. (October 2018) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)

|

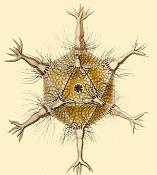

Circogonia icosahedra, a species of radiolaria, shaped like a regular icosahedron.

Many viruses, such as the herpes virus, have the shape of a regular icosahedron. Viral structures are built of repeated identical protein subunits and the icosahedron is the easiest shape to assemble using these subunits. A regular polyhedron is used because it can be built from a single basic unit protein used over and over again; this saves space in the viral genome.

In meteorology and climatology, global numerical models of atmospheric flow are of increasing interest which employ geodesic grids that are based on an icosahedron (refined by triangulation) instead of the more commonly used longitude/latitude grid. This has the advantage of evenly distributed spatial resolution without singularities (i.e. the poles) at the expense of somewhat greater numerical difficulty.

Geometry of space frames is often based on platonic solids. In the MERO system, Platonic solids are used for naming convention of various space frame configurations. For example, 1/2O+T refers to a configuration made of one half of octahedron and a tetrahedron.

Several Platonic hydrocarbons have been synthesised, including cubane and dodecahedrane.

A set of polyhedral dice.

Liquid crystals with symmetries of Platonic solids

For the intermediate material phase called liquid crystals, the existence of such symmetries was first proposed in 1981 by H. Kleinert and K. Maki.[8][9] In aluminum the icosahedral structure was discovered three years after this by Dan Shechtman, which earned him the Nobel Prize in Chemistry in 2011.Related polyhedra and polytopes

Uniform polyhedra

There exist four regular polyhedra which are not convex, called Kepler–Poinsot polyhedra. These all have icosahedral symmetry and may be obtained as stellations of the dodecahedron and the icosahedron. cuboctahedron |

icosidodecahedron |

The uniform polyhedra form a much broader class of polyhedra. These figures are vertex-uniform and have one or more types of regular or star polygons for faces. These include all the polyhedra mentioned above together with an infinite set of prisms, an infinite set of antiprisms, and 53 other non-convex forms.

The Johnson solids are convex polyhedra which have regular faces but are not uniform. Among them are five of the eight convex deltahedra, which have identical, regular faces (all equilateral triangles) but are not uniform. (The other three convex deltahedra are the Platonic tetrahedron, octahedron, and icosahedron.)

Regular tessellations

| Platonic tilings | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|

|

|

| {3,3} | {4,3} | {3,4} | {5,3} | {3,5} |

| Regular dihedral tilings | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| {2,2} | {3,2} | {4,2} | {5,2} | {6,2}... |

| Regular hosohedral tilings | ||||

|

|

|

|

|

| {2,2} | {2,3} | {2,4} | {2,5} | {2,6}... |

One can show that every regular tessellation of the sphere is characterized by a pair of integers {p, q} with 1/p + 1/q > 1/2. Likewise, a regular tessellation of the plane is characterized by the condition 1/p + 1/q = 1/2. There are three possibilities:

|

|

|

| {4, 4} | {3, 6} | {6, 3} |

|---|

|

|

|

|

| {5, 4} | {4, 5} | {7, 3} | {3, 7} |

|---|

Higher dimensions

In more than three dimensions, polyhedra generalize to polytopes, with higher-dimensional convex regular polytopes being the equivalents of the three-dimensional Platonic solids.In the mid-19th century the Swiss mathematician Ludwig Schläfli discovered the four-dimensional analogues of the Platonic solids, called convex regular 4-polytopes. There are exactly six of these figures; five are analogous to the Platonic solids 5-cell as {3,3,3}, 16-cell as {3,3,4}, 600-cell as {3,3,5}, tesseract as {4,3,3}, and 120-cell as {5,3,3}, and a sixth one, the self-dual 24-cell, {3,4,3}.

In all dimensions higher than four, there are only three convex regular polytopes: the simplex as {3,3,...,3}, the hypercube as {4,3,...,3}, and the cross-polytope as {3,3,...,4}.[10] In three dimensions, these coincide with the tetrahedron as {3,3}, the cube as {4,3}, and the octahedron as {3,4}.

See also

References

- Coxeter 1973, p. 136.

Sources

- Atiyah, Michael; Sutcliffe, Paul (2003). "Polyhedra in Physics, Chemistry and Geometry". Milan J. Math. 71: 33–58. arXiv:math-ph/0303071. doi:10.1007/s00032-003-0014-1.

- Boyer, Carl; Merzbach, Uta (1989). A History of Mathematics (2nd ed.). Wiley. ISBN 0-471-54397-7.

- Coxeter, H. S. M. (1973). Regular Polytopes (3rd ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-61480-8.

- Euclid (1956). Heath, Thomas L., ed. The Thirteen Books of Euclid's Elements, Books 10–13 (2nd unabr. ed.). New York: Dover Publications. ISBN 0-486-60090-4.

- Gardner, Martin(1987). The 2nd Scientific American Book of Mathematical Puzzles & Diversions, University of Chicago Press, Chapter 1: The Five Platonic Solids, ISBN 0226282538

- Haeckel, Ernst, E. (1904). Kunstformen der Natur. Available as Haeckel, E. (1998); Art forms in nature, Prestel USA. ISBN 3-7913-1990-6.

- Hecht, Laurence; Stevens, Charles B. (Fall 2004). "New Explorations with The Moon Model" (PDF). 21st Century Science and Technology. p. 58.

- Kepler. Johannes Strena seu de nive sexangula (On the Six-Cornered Snowflake), 1611 paper by Kepler which discussed the reason for the six-angled shape of the snow crystals and the forms and symmetries in nature. Talks about platonic solids.

- Kleinert, Hagen and Maki, K. (1981). "Lattice Textures in Cholesteric Liquid Crystals" (PDF). Fortschritte der Physik. 29 (5): 219–259. Bibcode:1981ForPh..29..219K. doi:10.1002/prop.19810290503

- Lloyd, David Robert (2012). "How old are the Platonic Solids?". BSHM Bulletin: Journal of the British Society for the History of Mathematics. 27 (3): 131–140. doi:10.1080/17498430.2012.670845.

- Pugh, Anthony (1976). Polyhedra: A visual approach. California: University of California Press Berkeley. ISBN 0-520-03056-7.

- Weyl, Hermann (1952). Symmetry. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02374-3.

- Wildberg, Christian (1988). John Philoponus' Criticism of Aristotle's Theory of Aether. Walter de Gruyter. pp. 11–12. ISBN 9783110104462

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Platonic solids. |

- Platonic solids at Encyclopaedia of Mathematics

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Platonic solid". MathWorld.

- Weisstein, Eric W. "Isohedron". MathWorld.

- Book XIII of Euclid's Elements.

- Interactive 3D Polyhedra in Java

- Solid Body Viewer is an interactive 3D polyhedron viewer which allows you to save the model in svg, stl or obj format.

- Interactive Folding/Unfolding Platonic Solids in Java

- Paper models of the Platonic solids created using nets generated by Stella software

- Platonic Solids Free paper models(nets)

- Grime, James; Steckles, Katie. "Platonic Solids". Numberphile. Brady Haran.

- Teaching Math with Art student-created models

- Teaching Math with Art teacher instructions for making models

- Frames of Platonic Solids images of algebraic surfaces

- Platonic Solids with some formula derivations

- How to make four platonic solids from a cube

No comments:

Post a Comment